In a windowless basement lab in Fredericton, New Brunswick, three white-coated researchers solemnly face a row of steaming boiled potatoes resting on numbered plates. At first glance, the tubers are identical, but closer inspection reveals variations: their exteriors range from crumbly to smooth, their tints from snowy to golden; on some, dark spots mar the creamy flesh. The scientists pick and prod the specimens with stainless-steel forks and assign each variety a score based on its colour, flavour, texture, and appearance. The researchers taste and smell as if they were sommeliers—and then scrape the leftovers into a plastic garbage bag.

The door swings open, and Benoît Bizimungu, senior potato breeder at the Fredericton Research and Development Centre, enters the room, holding aloft a fork with a merry laugh. His favourite days are the ones he spends in the field each September, but boil-and-bake day isn’t bad either. “Too bad you weren’t here on french fry day,” says one young researcher, sipping water to cleanse his palate. It’s a light moment in the midst of an otherwise serious task. This world-renowned lab, overlooking the Saint John River and surrounded by acres of silt loam, is focused on building a better spud.

Fifty years ago, the FRDC created the Shepody, a smooth-skinned, white-fleshed potato that revolutionized the Canadian frozen french fry industry. Potatoes are an important global staple, but they are also notoriously tricky to breed: the plant is a polyploid, with many hard-to-predict sets of chromosomes, so uniformity is difficult to guarantee.

First crossed in 1967, the Shepody potato was the product of hybridization between a Fredericton-bred variety, the unglamorously named F58050, and the Bake King, developed in New York. It was one of thousands of potatoes bred that year. To make good french fries, a potato needs certain characteristics: a long, smooth, slightly rectangular shape; low sugar levels, so it won’t burn during deep-frying; and a dry centre that will allow for a uniform cook. The Shepody checked every box. But most important for New Brunswick’s expanding McCain Foods, which was quickly starting to dominate the country’s potato trade, the Shepody was ready for harvest weeks before the Russet Burbank, then the most popular fry variety. The Burbank, originally bred in California, matures at around four or four and a half months; the slightly earlier season made possible by the Shepody meant less scrambling for year-round supply.

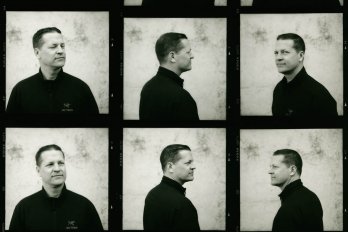

Richard Tarn came to the centre in 1968, after receiving his PhD from the University of Birmingham, and later joined the Shepody team. Tarn had spent most of the previous year collecting wild potato varieties in rural Mexico and looking for rare or remarkable traits that would enhance global breeding stock. McCain’s testing of the Shepody before its official release in 1980, says Tarn, was a large part of its success. Already pleased by test batches from its processing facilities, McCain was bullish, buying all the Shepody potatoes Maritime farmers could grow. The potato was swiftly adopted across North America and Australia, and in 1992, Tarn’s team was awarded a certificate of excellence by Agriculture Canada. The Shepody is now among the top french fry potatoes in North America. In 2015, Canadian businesses exported more than $1 billion in frozen potatoes, a large portion of which were Shepodys.

Developing new varieties of potato requires profound patience, a wonkish attention to detail, the management of huge data sets, and, according to Bizimungu, imagination. “You have to have a science background, but also an artistic vision and sense of discovery that will lead to innovation,” he says, striding through a white-walled room lined with pieces of state-of-the-art genomic testing equipment that resemble expensive photocopiers. Every year, his team manually crosses parent plants—selected based on which characteristics they are likely to transfer to their offspring—to produce new potato seeds. The tubers they produce are then grown season after season, and scientists follow each tiny plant from the lab, to the greenhouse in late winter, and to the field in early spring. After harvest in the fall, varieties are tasted and tested—and the lucky standouts make it through to another year.

As the breeders in Fredericton make selections, they keep an eye out for specific traits. Some varieties are chosen because they don’t bruise and discolour after cooking. Some pass in part because they resist diseases and pests, such as the Colorado potato beetle; in the global potato industry, insects cause approximately $5 billion in revenue losses each year. Other varieties currently in development are designed to slow down the digestion of starch, and so might one day offer diabetics a low-glycemic alternative. One deep-yellow potato—bred from South American stock—is filled with carotenoids, pigments found in carrots that may slow age-related eye disease. Some potatoes might look great and store well but if they taste bland or bitter they won’t make the cut.

Every winter, the federal government releases its most promising potatoes to Canadian farmers, breeders, and producers, who pay a $100 seed-handling fee for a chance to try out a new potato for two years. Then they can place bids—ranging from hundreds to tens of thousands of dollars—on exclusive licences, which grant them the opportunity to test the potato exclusively for up to three years and negotiate a contract to commercialize the variety. Every year, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, which runs the FRDC, collects an average of $5.3 million in intellectual property royalties from innovations in grains, technology, and farm machinery, which it says is “reinvested into research and development activities.” From potatoes still under licence, the government makes $16.50 per tonne of seed sold.

But because government breeders are increasingly focusing on the specific needs of large growers and processors, such as the frozen french fry industry, consumers are missing out on options. Tarn remembers being disappointed every time the team decided to cut a particularly delicious or handsome potato from the program. Sometimes it did so because of a single, crucial flaw: the tuber’s unsuitability for rough-and-tumble large-scale harvesting and processing. “No matter how good everything else is,” he says, “if the potato is going to shatter when it falls eighteen inches, it’s not going to survive.”

In the arms race for the perfect potato, large multinational companies push mid-sized or small family-owned farms towards cultivating profitable varieties. The Irish Cobbler, for example, an irregularly shaped, tan-skinned heirloom with a nutty aroma and a distinctive earthy flavour, was once grown across Prince Edward Island as a perennial favourite commonly sold at roadside stands. But not anymore: cooks in search of convenience didn’t want to dig out its deep eyes with a peeler. As scientists strive to provide the primary traits large processors want—more productive plants, or ones that need less fertilizer—Tarn says there’s a risk that researchers may be overlooking potatoes with other redeeming qualities, such as the Irish Cobbler’s pleasant taste, or the beauty of delicate, knobby pink fingerlings. Customers are used to buying generic potatoes labelled “red-skinned,” “yellow-fleshed,” “waxy,” or “new.” Even the legendary Shepody, when it makes it to grocery stores, is simply labelled “white.” The next super potato is out there—delicious, efficient, and resilient—with a yet-to-be-discovered combination of genes.

Next door to the FRDC’s kitchen and tasting room is an earthquake-proof gene bank that houses the bulk of Canada’s important potato genetic resources, primarily in the form of temperature-controlled seeds or seedlings. Included in the collection is the Lumper, the variety hit by blight between 1845 and 1849 that led to the Irish potato famine. Its history serves as a cautionary tale of what can happen when we rely on a single variety.

In the Fredericton lab’s sunny propagation room, Bizimungu, surrounded by bright- and olive-green potato seedlings in round glass beakers, is nursing some of the 80,000 seedlings, preparing them for planting in the spring. Come fall, he will trade in his lab coat for steel-toed boots, a floppy hat, and rain gear, and then once again head to the field where the next top spud may be waiting underground.