For a certain kind of girl—born in the ’70s or ’80s—the very mention of Jean M. Auel’s The Clan of the Cave Bear stirs up something. It’s not nostalgia: for many women, the 1980 novel was a gateway to the erotic, albeit in epic paleo packaging. Once the raspberry cordials of Anne of Green Gables and the sports cars of Sweet Valley High had become too innocent, we sought out sexual references wherever we could find them: Flowers in the Attic, The Blue Lagoon, The Mists of Avalon, and, of course, The Clan of the Cave Bear.

This was before the internet. Before sexting. Most of our fathers’ porn was out of reach—if we even wanted it, anyway. Meanwhile, Auel’s six-part Earth’s Children series, of which the 500-page Clan is the first title, has sold 45 million copies. Many of our mothers had one lying around.

Clan tells the story of Ayla, a beautiful blond Homo sapiens child who, after being orphaned by an earthquake, is raised by a clan of Neanderthals. Although blessed with some language and primitive medicine, the clan in which Ayla finds herself does not know etiquette as we define it today: among other caste and gender customs, they initiate sex via hand signal. Leaving aside the rather complicated nature of Ayla’s first sexual encounter (she’s about ten when it happens, and it’s not exactly consensual), the portrayal of sex in the clan overall is also lusciously graphic, with mentions of ripe females, loincloths, male organs that are “thick and throbbing,” and climaxes that culminate in an eruption of “built up heat.”

The historical fiction genre has never really seen another blockbuster like Clan. And in spite of the proliferation of erotic tastes online, and a society theoretically more accepting than it was thirty years ago of the kind of soft-core erotica most likely to be read by women (think Fifty Shades of Grey), perhaps we need one. Our fascination with the Neanderthal hasn’t really gone away—in fact, it’s growing, fuelled by new research and also by fads such as paleo diets and CrossFit workouts.

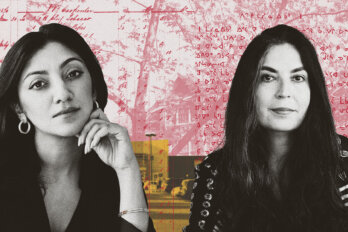

In her newly published novel, The Last Neanderthal, Toronto writer Claire Cameron cuts back and forth between a family that lived around 40,000 years ago and the activities of Rosamund Gale, a present-day archaeologist excavating Neanderthal sites in France. In one scene, Gale travels to a museum to sell its administrators on her findings. “Modern humans . . . developed a certain kind of story about the Neanderthals that played to their benefit. It’s a story that we continue to tell. It’s the story we should challenge,” she says, making a point that also acts as a kind of thesis statement for the book. Rather than highlighting the brutishness of Neanderthal life portrayed in Clan, Cameron is interested in exploring our common ground.

In 2010, a team of scientists published a draft of the Neanderthal genome, showing that Neanderthals shared 99.7 percent of their DNA with humans. Nevertheless, Homo neanderthalensis are believed to have constituted a distinct species. Though Neanderthals have been extinct for 40,000 years, recent research suggests that modern humans—at least in Europe and Asia, where Neanderthals lived—inherited between 1 and 4 percent of their DNA from Neanderthals, which suggests that there was interbreeding among humans and Neanderthals for at least some of the roughly 5,000 years they coexisted. This fact suggests that the stereotypically unsophisticated, grunting caveman might not, perhaps, have been so different from humans of the same time period. Cameron, whose last book, The Bear (nominated for the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction), dealt with survival in the wilderness, followed the news with some excitement. “It really struck me that the head of this project said Neanderthals were much more like us than we ever thought,” she told me. (For the record, DNA tests show that Cameron is 2.5 percent Neanderthal, but she was hoping to be more like 4 percent.) It was after seeing a cave while snowshoeing in the Niagara Escarpment that the author started to think about how Neanderthals might have lived during the Ice Age. Cameron, forty-four, says she read Clan in high school, but has not returned to it since (“It is [for] when Judy Blume’s no longer dirty enough”).

“You’ve never seen such a magnificent creature,” Cameron writes in her prologue. Her Neanderthal heroine Girl is anything but grotesque. Here she is, setting out to kill some bison:

She knew how she looked, dressed for the hunt with hardened hides strapped tight to her shins and forearms. The black ocher paint on her face showed the two streaks of the family on each cheek. A shock of red hair stood up from her head. She wore a single shell on a thin lash around her neck. Her skin smoothed over muscles and gleamed with hazel oil.

Girl’s hunter-gatherer family in the late Ice Age world spends almost all its time on basic survival—from stocking up on food to defending itself from predators such as bears and leopards. At its head is the aging Big Mother, now so old “there were more than thirty springs she could remember,” whose breasts lie flat over her belly, whose chin is whiskered, and who has so many missing teeth that Girl must chew her food for her, the way that birds do for their chicks or the actress Alicia Silverstone did for her son, Bear Blu.

Fecundity is another key to survival. Each spring, Neanderthal families gather to fish and scope out possible mates. Big Mother has had six children—Cameron, with a diagrammatic style that echoes Clan, provides a family tree for her characters—and also takes on one adopted human foundling, Runt. “In her prime, Big Mother had sought out the penises of the strongest men,” writes Cameron. “They left their mark in her and lots of fluid got inside.”

Alas, it turns out that the title of Cameron’s book is literal: this is the last remaining Neanderthal family. The book doesn’t concern itself very much with how the rest of the population disappeared. Cameron told me that prior to her research, she had always assumed that humans wiped out the Neanderthals: “I thought [Homo sapiens and Neanderthals] fought, and it was a power-grab thing.” But the evidence in our DNA shows that our cave-age ancestors interbred with Neanderthals. As a museum curator puts it in one of the contemporary sections of the book, “Sex or violence—which is the more compelling story?”

It’s sex, of course—ask anyone drawn to the story of Ayla in Clan of the Cave Bear, or who is a contemporary aficionado of Amazon’s “dinosaur erotica” section (a small but dedicated tab with such titles as Taken by the Pterodactyl). One thing Cameron pondered while writing her new book was how human-Neanderthal sex came to be, and “if it was any good.”

Sadly, there are no scenes of such intercourse in this book, but plenty of other taboos are represented. By page thirteen, there have been several references to the morning erections of Him, Girl’s brother (or perhaps, given the noted prolific sexual nature of their Big Mother, more like her half-brother). “Big Mother laughed with joy, as an erect penis signaled good health,” Cameron writes. “It was happiness.”

I took this content to be a kind of site-specific Chekhov’s gun (“If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired”). As Cameron explained to me, if these Neanderthals are among the last of their kind, they will make do. “There’s not that many people around to have sex with—and they’re teenagers.”

Incest is nonetheless frowned upon by Big Mother, who regularly relays a story via shadow puppets—the Neanderthals don’t use spoken language—about a brother and sister who “developed a taste for each other” and travelled to the sea, where “their lips became crusted with the salt water that they drank. They grew claws for their hands and started to look like the creatures they ate . . . It was a story they all loved, the horror and delight twisted together tightly.” We learn that the shell necklace Girl wears is a totemic reminder of the terrible oceanic fate of one who succumbed to a crush on her brother—a prehistoric purity ring, if you will.

To make things worse, Girl is in her first heat. Hormones and population scarcity are such that eventually no one—not Girl, not Him, not Cameron, definitely not the reader—can withstand the escalating sexual tension. We are rewarded with a lengthy description of incestuous Neanderthal sex. A leopard watches them from a perch.

He lifted her hips so that her thighs spread over his. With a grunt, he pushed in. Unsure, unsteady for a moment, there was a wobble and then she wiggled. And that was right. He felt a glow like a hot ember move up from his groin and spread out. He was filled by the heat of her body and with the rhythm of how she moved and the smell of earth around them.

As in Clan, the sex is earthy and fuelled by the basest of desires—in Cameron’s words, “more a compulsion than a choice.” Certainly, it portrays the opposite of what Rose the archaeologist is experiencing with her vexingly mild and supportive professor partner, Simon, who comes from their home in England to visit her on site in France. After a long separation, the best sex they can muster arises after he massages her feet on a daybed. Because Rose is pregnant, they struggle with a few positions. “We were usually fairly seamless in reading each other’s needs, but this time required a fair amount of conversation, giggling, and adjustment. We ended up making it work with Simon crouched over top as I lay back with my legs to the side. It must have felt like making love to a hot-water bottle for him, but he’s never been picky.” The high point comes afterwards, when Simon makes what she calls “the best grilled cheese I had ever eaten,” garnished with her favourite brand of ketchup.

Sex, in this landscape of Cameron’s, can be portrayed between primitives more readily than bourgeois couples. It makes our own accoutrements such as lingerie, perfume, bikini wax, sex toys, and Viagra seem like pathetic props supplied only to guide us back to a more Edenic state.

My own erotic landscape may no longer be bound by the books lying around in my parents’ bedroom, but Clan made a lasting mark on my psyche. The insight that those of us who had our first sexual awakenings via The Clan of the Cave Bear can provide is that Neanderthal sex is real sex—the same attraction is what draws us to inhale a partner’s dirty T-shirt, or a musky perfume. It might be gross on one level, but it hits our brains in a place beyond reason. We just want it.

I asked Cameron whether she thought one could write about Neanderthals without writing about sex. “Yes, definitely,” she said. But why would you want to?

This originally appeared in the May 2017 issue.