The O’Hagan Annual Essay on Public Affairs is a research-based examination of the current economic, social, and political realities of Canada. Commissioned by the editorial team at The Walrus, the essay is funded by Peter and Sarah O’Hagan in honour of Peter’s father, Richard, and his considerable contributions to public life. Richard O’Hagan is a member of the Walrus Foundation’s board of directors.

In the dwindling light of a winter afternoon, amid the northern sprawl of Winnipeg, a line of school buses turns slowly into a parking lot outside Maples Collegiate. The high-school students have already left for home. Most of the bundled-up children who clamber out of these buses are between five and twelve years old. They arrive here three afternoons a week in their hundreds, not to practise sports, not to learn arts, but to retain or regain their ancestral languages.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more Walrus audio, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Indoors, emerging like butterflies from the chrysalises of snowsuits, the children offer a glimpse of tomorrow’s Winnipeg—tomorrow’s Canada—that is very different from the past. Those heading to classes in German, Italian, or Polish are mostly second- and third-generation Canadians. Their teachers work on conversational skills—“so, when the kids are at a family gathering, they can start to participate,” says Cathy Horbas, who oversees the Heritage Languages Program for the Seven Oaks School Division. By contrast, most of the children entering the five classes in Punjabi or the three in Filipino are new Canadians who already speak the family language; their focus is on reading and writing it. Their parents grew up in societies where it’s normal to be fluent in several languages, unusual to speak just one.

And then there are the kids whose grandparents or great-grandparents knew the languages of the river valleys, the plains, the unending pine forests of Manitoba. The kids who come to Maples Collegiate in hopes of learning Ojibwe or Cree. The kids who will sleep tonight, many of them, not among their own families but in the homes of those paid to look after them. Last fall, the federal government declared the overrepresentation of Indigenous children in Canada’s child-welfare system to be a humanitarian crisis—in Manitoba alone, nearly 90 percent of children in foster care are Indigenous. When they’re placed with non-Indigenous families, it’s not just a language that’s missing from their young lives—it’s an entire culture.

“We have to be careful how we address the children,” says Barbara Nepinak, an Ojibwe elder who visits the after-school program regularly. (Ojibwe is often written Ojibwa or Ojibway. The language is also known as Anishinaabemowin.) “We can’t dwell on family relationships, because there’s a disconnect. Most of the children have foster mothers, often from the Philippines. They’re fine, loving people, but they don’t understand the culture.”

Winnipeg rises on the land of Treaty One, the first of Canada’s eleven numbered treaties, and at 93,000, its population of Indigenous residents exceeds that of any other Canadian city: it has the largest number of First Nations people and of Métis people. By definition, their languages were never foreign here—that’s what “indigenous” means. But, in a city where one in four people were born outside Canada, a city of 700,000 echoing with voices from India and Latin America and the Philippines, Indigenous languages seem alien to many. Winnipeg is, in this light, a microcosm of the whole country—and the languages that ebb and flow through its wide streets speak volumes about Canada’s evolving identity.

It never takes much in Canada to make language a political issue. A century ago, debates on the topic were crystallized by the so-called Manitoba schools question. In 1916, the Thornton Act, named for Manitoba’s education minister, R. S. Thornton, shut down the entire French-language education system in what Louis Riel had helped found as a bilingual province, making English the only language that could legally be taught in public schools. Its proponents heard the music of languages other than English as a danger, a weakness, an embarrassment. Two years later, Thornton declared: “Our aim is to plant Canadian schools with Canadian teachers setting forth Canadian ideals and teaching the language of the country.” In the same period, Ontario and Saskatchewan took similar anti-French measures.

The emergence of a separatist movement in Quebec in the 1960s spurred the federal government to declare Canada a bilingual country: next year will mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Official Languages Act. Its provisions, along with those of the Constitution Act of 1982, give speakers of English and French the right to be served in their own language in all federal institutions and courts as well as the right to receive public education in either official language. But the celebrations may well be muted. For, as the multilingual nature of Winnipeg suggests, the Official Languages Act incarnates a vision of Canadian identity that, to many people, seems less and less relevant.

One reason is the continued erosion of French outside Quebec. Another is the explosive growth of non-European languages, including Mandarin, Cantonese, Arabic, Punjabi, and Filipino; each of them now has more than half a million speakers in Canada. A third, crucial reason is the federal government’s desire to pass an Indigenous-languages act before the 2019 election—a direct response to the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The report, issued in December 2015, asked the government to pass an Indigenous-languages act and appoint a commissioner to oversee it; it called on universities to create degree and diploma programs in these languages; it used the phrase “Aboriginal language rights.” In the past eighteen months, Canadian Heritage, the department responsible for drafting the act, has been prioritizing the file.

The act is, in the prime minister’s words, being “co-developed” by the government and three national Indigenous organizations. It’s expected to give formal recognition to the dozens of Indigenous languages still spoken here and to commit long-term funding for their maintenance and recovery.

Will the price of the new Indigenous-languages act and large-scale immigration in recent decades be Canadians’ long-held belief in linguistic duality? Laws that were passed when Pierre Trudeau was prime minister enshrined English-and-French bilingualism as a key principle of Canadian public life. But, in the era of Justin Trudeau, the future appears multilingual—a complex verbal landscape in which Indigenous languages enjoy an official place. Half a century ago, doubts about the identity of Canada as a bilingual country were expressed mainly by English Canadian diehards and Quebec separatists. Today, as the voices of Indigenous communities and new Canadians gain volume, those doubts are much more varied—and they’ve taken on a different tone. Canada’s core language tension now focuses not just on the prominence of French at an official, national level but also on a growing self-awareness that ours is a country shaped by far more than the legacies of two colonial empires.

Derrek Bentley steps into a handsome building that houses the Centre Culturel Franco-Manitobain in St. Boniface, an old neighbourhood of Winnipeg that was once a separate city. Streets here are still named Jeanne d’Arc, La Vérendrye, Louis Riel. None of Bentley’s ancestry is French. Yet, at twenty-four, he’s the president of Conseil jeunesse provincial—a Manitoba group that is, he explains over coffee, “run by and for youth, so they can live in French culture in their own way.”

For a long time, Manitoba’s conseil jeunesse served only those whose mother tongue was French. Then it expanded to include people, like Bentley, who are francophone—and francophile—by choice. Bentley attended French-immersion school as a child. In grade nine, fearing he might lose his second language, he fought for the right to switch into an entirely French high school. There are twenty-three schools for francophone students scattered across the province, and they have been run, since 1994, by a school board of their own. R. S. Thornton must be turning in his grave.

Now the conseil jeunesse also strives to welcome multilingual newcomers from countries such as Congo and Rwanda. “The community has realized,” Bentley says, that “conversations can become more and more vibrant with these multicultural backgrounds.”

The resources that Ottawa makes available to French speakers outside Quebec—and to English speakers in Quebec—are often generous. It’s no surprise that many Indigenous leaders see the Official Languages Act as a wonderful precedent for an Indigenous-languages act. But Franco-Manitobans have often had to battle hard for their rights. In the 1980s, when French speakers were urging the province to offer bilingual services, the offices of the Société de la francophonie manitobaine were destroyed by arson. A so-called Manitoba Unity Committee sprang up, its goal being to prevent “creeping bilingualism.”

Today, French is a marker of cultural prestige. Among middle-class parents with aspirations for their kids, in Winnipeg as in many other cities, French immersion is a desirable choice—despite the lack of genuine fluency with which most students graduate. But across the province, the everyday use of French is on the decline. Whereas the 1971 census showed that 60,485 Manitobans spoke French as a mother tongue, by 2016 the figure had fallen to 40,520. These numbers are emblematic of the broader struggle for all francophones outside Quebec: If the language keeps on shrinking in its historic western stronghold, what chance does it have in Halifax or Hamilton? Except for New Brunswick—francophones make up just over 30 percent of people in Canada’s only officially bilingual province—no province outside Quebec now has a mother-tongue francophone population of even 4 percent. “The question of numbers is important,” says Graham Fraser, who served as Canada’s official-languages commissioner between 2006 and 2016. “One of the things that has made the application of the Official Languages Act easier to understand is that there are 4 million French-speaking Quebecers who don’t speak English.” Rights don’t depend on numbers. Services often do.

The Official Languages Act did not try to correct demographic imbalances, nor was it designed to reduce the rights of English speakers; it merely aimed to give French speakers equal rights. After it was passed in 1969, linguistic duality became a widely accepted goal among English-speaking Canadians, and bilingualism has since become a cornerstone of Canada’s global image.

Yet, last year, even a federalist government in Quebec felt compelled to support a Parti Québécois motion denouncing the widespread use of “Bonjour, hi” as a greeting in stores and businesses. “The federal government has struggled for decades to get civil servants to say ‘Hello, bonjour,’” observes Fraser. This bilingual greeting, known as an “active offer,” is meant to indicate that federal services are available in both official languages. Salespeople in Montreal, says Fraser, have casually embraced the idea. But a level of bilingualism that in most of Canada might be applauded, officially at least, is condemned by nationalist Quebecers as a threat. Montreal has more trilingual residents than anywhere else in Canada, and the limited space French occupies in the city is a subject of constant debate—especially considering the erosion of French outside Quebec. Nearly half of all Quebecers are able to carry on a conversation in both official languages; in the rest of Canada, just under 10 percent of people can do so.

Census data from 1996 show that the number of mother-tongue francophones in Canada exceeded that of people with a non-official mother tongue (anything other than English or French) by more than 2 million. By 2016, the picture was very different: mother-tongue francophones are now fewer in number than those who speak a non-official mother tongue. A generation from now, will the French-speaking community in Manitoba—or anywhere else outside Quebec and parts of New Brunswick—still be vibrant?

To some, that’s not the right question to ask. Akoulina Connell, CEO of the Manitoba Arts Council, spent much of her career in Quebec and New Brunswick before moving to Winnipeg. Fluently bilingual in French and English, she’s aware of the sensitivities, political and linguistic, that come with any debate touching on the place of French. “But in a post-TRC context,” she insists, “we have a stronger awareness of the deep social wrongs that have been perpetuated by both francophones and anglophones. Linguistic duality is a colonial concept.” Parts of immigration policy, Connell suggests, are geared toward reinforcing the power of the two colonizing languages.

“I don’t want to use the word ‘resentment,’” says Melanie Kennedy, who directs Indigenous Languages of Manitoba (a non-profit group funded by the province), “but there’s certainly some envy of Franco-Manitobans. It seems so simple for them, as opposed to how hard we have to fight. You can only do so much with no money.” But Derrek Bentley, looking at things from a Franco-Manitoban standpoint, insists that “it’s always an upstream battle for any minority community. There’s so much work involved in getting the services and resources so the community can flourish.”

And, indeed, protecting French language rights and preserving Indigenous cultures are not mutually exclusive.

“What distinguishes us from our southern neighbour,” says Justin Johnson, “is the idea of [official] bilingualism.” At twenty-six, Johnson is the president of the Fédération de la jeunesse canadienne-française. He comes from the small town of Lorette, historically a Métis encampment—La Petite Pointe des Chênes. His great-great-grandfather André Beauchemin was part of Louis Riel’s provisional government in 1870. “But we never talked about it,” Johnson admits. When he was growing up, he says, most of his mother’s family spoke English, and they weren’t proud of their Métis and French past—it felt like a burden.

Today, Johnson is happy to call himself both Métis and French Canadian. “Our ideas founded the country,” he says. “And they should be seen in a modern context. Bilingualism, religious liberty—these notions are part of the Canadian character. The reason the French community is vibrant now are the Métis people who shed blood on the plains.” The resistance that Louis Riel led in 1870 aimed to preserve Métis rights to practise the Catholic faith, use the French language, and maintain their own culture.

Johnson doesn’t speak Michif, a language of the Métis people. Only about 200 people in Manitoba do. And yet—such are the complexities the government has to navigate in preparing an Indigenous-languages act—Michif can’t be overlooked. It fascinates linguists, having long been seen as theoretically impossible: it consistently marries the nouns of one language (French) with the verbs of another. Across the Prairie provinces, the language’s Indigenous element is Cree, often mingled with Ojibwe; according to a Michif language instruction website, the question “Where do your grandparents live?” would be expressed, “Taande tes granparaan aywekachick?”

Michif has not been standardized, nor was it ever the language of all Métis people—many of them spoke French, others quickly adopted English, and a few developed a now near-extinct idiom known as Bungee (it interwove Cree with Scots Gaelic). Yet, thanks to the precarious survival of Michif—in all of Canada, a little more than 1,000 people, less than 0.2 percent of all Métis people, according to census data, can speak one or another form of the language—the Métis National Council has been asked to “co-develop” the Indigenous-languages act, along with the Assembly of First Nations and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. The difficult question is: What can the act reasonably be expected to achieve?

“It’s shocking to me how many Canadians don’t know the meaning of the name Canada, the name Manitoba, the name Winnipeg,” says Niigaan Sinclair, a professor in the Department of Native Studies at the University of Manitoba. (He is also a member of this magazine’s educational review committee.) When it comes to place names, “it means we have an illiterate citizenry.”

“Two things have to happen in the act,” Sinclair says. His father, Senator Murray Sinclair, chaired the TRC, the final report of which called for the creation of the act. “First, Indigenous languages must be recognized as founding languages of the country—all of them. And second, there have to be the resources and support to ensure these languages carry on into the future. Without these two things, reconciliation is impossible.”

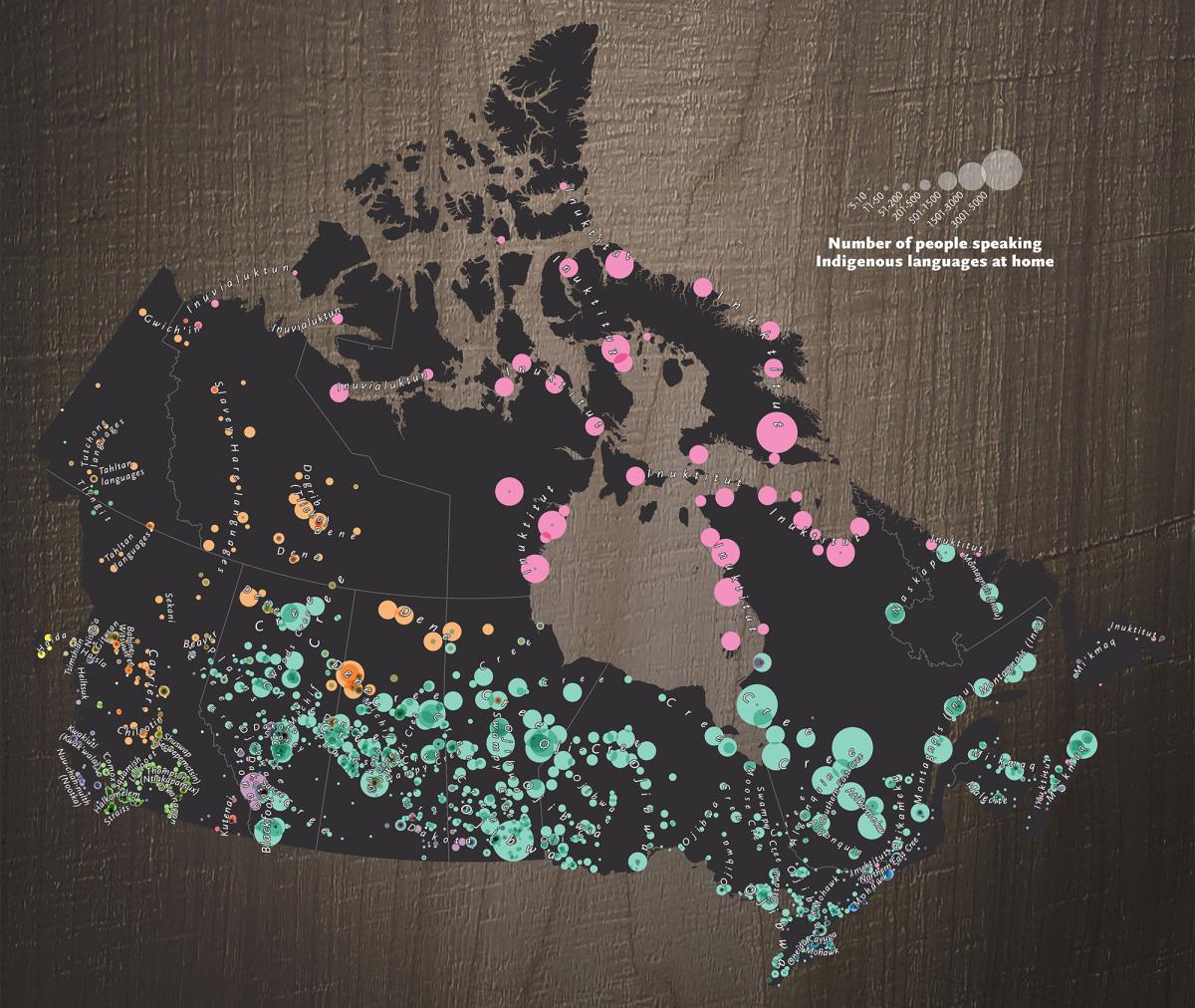

When Sinclair says “all of them,” he means it. Some people have quietly wondered if the passage of an Indigenous-languages act might lead to a sort of language triage, whereby widely spoken tongues, such as Ojibwe, receive a healthy infusion of funds but languages with few speakers are merely documented for posterity, no serious effort being made to revive them. In British Columbia, according to the 2016 census, 8,435 people spoke an Indigenous language as their mother tongue. This total was split among almost fifty languages (not just dialects), many of them near death’s door. Only one, Carrier, still had a thousand mother-tongue speakers. Yet Sinclair dismisses the notion of language triage: “That’s so disrespectful—it’s [a] violent idea. There’s nothing more colonizing than defeatism.”

Geography further complicates the matter. Cree, Inuktut, and Ojibwe—the three Indigenous languages with the largest number of speakers—all stretch over vast areas of Canada. The result, in each case, is a bewildering variety of dialects. Because of the lack of standardization, most of the course materials developed to teach these languages apply to only a single region. Ojibwe, as spoken across much of Ontario—and in the US, where it’s known as Chippewa—differs from the language in Manitoba.

What Sinclair calls “resources and support” could mean an economic boost for Inuit, First Nations people, and Métis people. That’s because, especially in the North, many high-status jobs in teaching and administration exclude local people. (As a side effect, such jobs also exclude most immigrants.) They require English-French bilingualism instead—whether or not the employees have any connection with the local community. Under the Canada-Nunavut General Agreement on the Promotion of French and Inuit Languages, the federal government now provides nearly as much funding for the 630 mother-tongue francophones in Nunavut as it does for the 22,600 people who speak an Inuit mother tongue.

In 2017, the Trudeau government committed almost $90 million over three years to support Indigenous languages. When Arif Virani—parliamentary secretary to the minister of Canadian heritage and a key player in developing the new legislation—spoke to the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) last year, he promised that, under an Indigenous-languages act, stable, long-term funding would be provided: “We’re not keen on drafting legislation that becomes a symbolic white elephant.”

Virani is a Toronto lawyer and a refugee from Uganda. The minister responsible for the legislation, Mélanie Joly, is a Montreal lawyer. Interviewed one afternoon near Montreal’s Old Port, she admits that when Trudeau asked her to come up with a new law, “I wasn’t as aware of Indigenous issues as I am now. I’ve learned a lot,” she says. “But, as a francophone, I really understand the importance of language and identity.”

Indigenous leaders have told Joly the act should recognize Indigenous languages as a right under Section 35 of the constitution—the section that now affirms “existing aboriginal and treaty rights”—and place control over language funding in the hands of Indigenous people themselves. Although a final decision has not yet been taken, it seems likely that the act will also establish the offices of three language commissioners (one each for Métis people, First Nations, and Inuit). “The social contract in Canada,” Joly suggests, “is based on three pillars. First, there are two official languages. Second, we protect minorities and we support multiculturalism. Now we’re adding the third pillar: reconciliation. That’s fundamental to our social contract.” None of those pillars, it’s worth noting, were in place before the late 1960s.

But will reconciliation erode bilingualism? When asked if an Indigenous-languages act means that Canada will soon be officially multilingual, Joly hesitates: “It’s too soon to have that conversation.”

Many of the kids in the Heritage Languages Program arrive at Winnipeg’s Maples Collegiate tired and hungry—it is, after all, the end of a long school day. Barbara Nepinak and Clarence, her husband, bring them a snack. Then, acting like surrogate grandparents, they tell the children stories and teach them Ojibwe words: nouns and verbs from daily life. But there’s only so much a child can pick up between 4:00 and 5:30 p.m., three days a week. To acquire real fluency, you need to go further and deeper. That’s why the Seven Oaks and Winnipeg School divisions now offer a bilingual program in Ojibwe and English, one that will stretch from kindergarten to grade five. The challenge is not in finding children to learn Cree and Ojibwe but in recruiting adults who are qualified to teach them.

Riverbend Community School, also in Winnipeg’s northern suburbs, has taken up the challenge. “I’m a traditional person,” says Audrey Guiboche, who came out of retirement to teach here and to create part of the Ojibwe curriculum. “I’m a sun dancer, a pipe carrier, a sweat-lodge keeper. I live the life. I’m just blown away by the fact that I’m getting paid to teach the language.”

She is sitting on the only adult-sized chair in a cramped office. A wall chart behind her shows the months and seasons, set into a large circle. The key concepts for biboon (winter) include animal hibernation, star teachings, and elders. Ziigwan (spring) will focus attention on community, cradles, and the cycle of life. “The kids are hungry for self-knowledge,” Guiboche says. “In one of the classes here, 85 percent of them are in foster care. I see the work I do as having a sacredness to it. It’s geared to making them think about their inner world.”

At the University of Manitoba, the crippling shortage of qualified teachers led the Department of Native Studies to make a startling hire: one of its Ojibwe-language instructors is a third-year undergraduate at the University of Winnipeg. Aandeg Muldrew, admittedly, is no ordinary linguistics student. He learned Ojibwe as a child from his grandmother Pat Ningewance, who teaches the language today at Algoma University in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. Algoma’s main building began its days as the Shingwauk Residential School—and, Muldrew says, “my grandma’s office is on the same floor as where her bed used to be.” His youthful fluency is unusual: across Canada, only about 15 percent of young First Nations people can hold a conversation in their ancestral language.

For various reasons, statistics are not entirely reliable, but it’s clear that in recent decades, Ojibwe has suffered a serious decline. Of the eight most-spoken Indigenous languages, Ojibwe has the lowest percentage of mother-tongue speakers who continue to use it as their primary language. Census data show that, in 1996, Ojibwe had 25,885 mother-tongue speakers; by 2016, the total had fallen to 20,470—less than half of whom reported the language as the one they spoke most often at home. (Another 13,465 people spoke, as their mother tongue, the hybrid language of Oji-Cree.)

Speakers of Indigenous languages, and would-be speakers, feel they can’t just sit around and wait for legislation to help them. “Indigenous youth in this neighbourhood are experiencing racism daily,” says Jarita Greyeyes, the director of community learning and engagement at the University of Winnipeg. “They’re feeling the effects of over-incarceration and over-policing in their neighbourhoods, some of their family are being misapprehended by the child-welfare system—but culture and language insulate them from some of these harms. They get all the beautiful parts of the culture that are embedded in the language.” That idea of language as a spiritual vaccine is not fanciful. One BC study found the suicide rate in First Nations communities with a high rate of language retention to be far lower than in places where the language has been lost.

Greyeyes works out of the Wii Chiiwaakanak Learning Centre, a storefront space in the city’s core. Almost 13 percent of first-year students at the University of Winnipeg are Indigenous, and the Wii Chii centre tries to bridge the gap between the university and the inner city. Its programs—free and open to everyone—have included Ojibwe immersion, sacred hoop dancing, and Pow Wow Club. As a Cree woman, Greyeyes looks on language as a “thread that links us to this land, these ancestors.”

Not that the Cree and Ojibwe threads are static. Barbara and Clarence Nepinak, who grew up in rural Manitoba, sense a difference in the words they hear today. “There’s many of us Ojibwe in the city,” Clarence says. “But, even within our own language, we speak a Winnipeg dialect.” “The younger people shorten the words,” Barbara explains. “And they mix English into the conversation.” That’s a typical concern for minority languages—speakers of French and Filipino here notice a similar trend—but for a land-based language such as Ojibwe, the changes can be disconcerting. You can’t speak it fluently if you drop Ojibwe words into English sentence structures: “Ojibwe operates from a whole different range of ideas, put together to express and describe the environment,” Clarence says. “The environment dictates what the language is going to be. With us, the sense of time is different.”

But the environment for the kids at Riverbend Community School and Maples Collegiate is one of Instagram and pickup trucks, YouTube and SUVs. Cranes and eagles, loons and bears: these are among the traditional clan symbols of the Ojibwe. Many of the Winnipeg children trying to learn Ojibwe have likely never seen those animals in the flesh.

Yet all languages and cultures evolve. Vania Gagnon, the director of the St. Boniface Museum, is a seventh-generation Franco-Manitoban. She’s untroubled by what some people hear as an insidious decline in the quality of her language. In French, she explains, “you’d say, ‘je m’en vais magasiner.’ I might say, ‘je m’en vais shopper au mall.’ My kids don’t even use the infinitive—they wouldn’t say, ‘je vais te texter,’ they’d just say text as a verb. It annoys some people—‘The language is being massacred!’ they say.” Throughout Franco-Manitoban history, “people turned their backs on French because they were criticized so harshly for making mistakes. And by teachers, mostly.”

For Gagnon, there’s no point in being afraid of the future: “Sometimes the nuances are better with a different word. Franglais is just a new Michif!”

In 2007, the school-programs division of the Manitoba government proposed a detailed curriculum stretching from kindergarten to grade twelve and applicable to all seven of the province’s Indigenous langauges. But the plan bore little relation to the actual state of these languages and made unrealistic assumptions about resources and teaching staff. And so years of work by twenty-one elders, thirteen youth advisors, seven members of a project advisory team, twenty-seven members of an Aboriginal languages and cultures curriculum project team, and nine members of the education department’s staff ultimately achieved very little.

Some community-based initiatives have been much more successful. Brian Maracle—Owennatekha, to give his Mohawk name—is the coordinator of Onkwawenna Kentyohkwa (“Our Language Society”) at Six Nations in southern Ontario. A former Globe and Mail reporter and CBC Radio host, he was not a childhood speaker of Mohawk. But he and his wife, Audrey, were determined to master their language, and created a program that has succeeded in transforming young adults who could say almost nothing in Mohawk into graceful speakers.

The program relies on immersion, six hours a day, eight months a year. A resident of Six Nations who commits to this effort is paid a stipend—though less than the minimum wage—by the Haudenosaunee Confederacy chiefs. (The band council pays Maracle’s salary and other expenses.) “They see we’re getting results,” Maracle says. “A dozen kids are growing up who speak it as their first language”—the sons and daughters of people who have put in the 2,000 classroom hours that Maracle believes are required to attain reasonable fluency. The program covered two years at first; today, it stretches to a third, complete with research projects and “philosophical discussions.” Maracle has also created an online course for people who can’t spend years at Six Nations. One-third of all participants on the course have been non-Indigenous, some from as far afield as Denmark, Brazil, and Mongolia.

Among those participants is Marc Miller, the Liberal MP for a chunk of inner-city Montreal. After months of study, he rose in the House of Commons in 2017 and delivered a statement in Mohawk; he believes it was the first time a non-Indigenous MP had ever spoken an Indigenous language in Parliament. Not only did he get a standing ovation, his speech also “touched a chord with lots of people you wouldn’t expect,” he recalls. “An immigrant wrote to me to say, ‘I struggle every day to make myself understood in English. Because I talk with an accent, people assume I think with an accent.’”

Speakers of endangered languages elsewhere in North America have launched projects based on Maracle’s. If the course at Six Nations serves as a model for other communities, and if the Indigenous-languages act provides them with stable long-term funding, Maracle’s work could become the most powerful catalyst for saving languages anywhere.

Mata, a Filipino teacher has written on a blackboard beside an outline of a human body. Binti. Bibig. As a bitterly cold afternoon turns to evening outside Maples Collegiate, he’s addressing children in grades two and three, some of whom wear their snowsuits indoors. They are not the only Winnipeg kids attending an after-school program in Filipino; five other schools host a similar class. This course isn’t about saving a language, it’s about valuing the culture of what has become the city’s most prominent immigrant population. Thanks to the rapid growth in the Philippine community, the Seven Oaks School Division is launching a Filipino bilingual program this fall. Children enrolled there will be immersed in the language every day.

Nobody would have predicted, half a century ago, that the Philippines would become Canada’s leading source of immigration. And even if Toronto has the largest number of Philippine immigrants, Winnipeg is the city where they make up the highest percentage of all residents. At least 50,000 people here speak a mother tongue from the Philippines. The most common one is Filipino (a composite based on Tagalog, the idiom of Manila and surrounding districts). Aside from English, Filipino is now the most widely used language in Winnipeg, Edmonton, and Calgary.

Most of its Canadian speakers live in major cities. But not all. Neepawa, the childhood home of the Manitoba author Margaret Laurence and an inspiration for her iconic novels The Stone Angel and The Diviners, now contains a huge slaughterhouse and pork-processing factory. The workforce overwhelmingly speaks Filipino. Neepawa had, according to the 2016 census, a population of 3,939, about 1,060 of whom named a language from the Philippines as their mother tongue.

“It’s the second language of Manitoba. We defeated the French!” crows Rod Cantiveros, the publisher of Filipino Journal and the owner of Hot Rod’s Grill. In the summer, it’s a food truck familiar to Winnipeg’s festival goers; in the winter, it’s a café housed in a Ford dealership on the highway to Gimli. The dealership advertises a special: Oil Change and Breakfast. Over a longadog—a sweet and spicy Philippine hot dog—Cantiveros explains what he’s learned since arriving in Winnipeg in 1974. “If the music here is tango, then tango,” he tells new immigrants. “Don’t cha-cha. Go with the music.” Perhaps Filipino speakers can do this without too much heartache because their language is secure at home.

It’s possible that, in Canada, Filipino will eventually go the way of Yiddish, Icelandic, Gaelic, and other immigrant languages of the past. All of them were once prominent in Manitoba; none is prominent now. But, at the moment, it can be a competitive advantage for a Winnipeg business to flaunt its prowess in Filipino and other languages. A Toyota dealership in the city’s north end makes a promise on its website: “We are proud to speak English, Punjabi, Tagalog, Hindi, Arabic, Portuguese, Polish, Ukrainian, and French.” The order is revealing.

Already, several of the city’s churches survive only thanks to Philippine immigrants, with services taking place in both English and Filipino. People from other traditions are equally keen to sustain a heritage language for the purposes of worship. Winnipeg has private Islamic schools where Arabic is a core subject. It has a private Jewish school in which Hebrew is taught at every level. And it has a private school for Sikh children—“the preservation of the Punjabi language and our rich cultural heritage” is a stated mission. Today, all this may seem natural and normal. But fifty, even thirty, years ago, it would have come as a shock.

The rapid and sustained growth of immigrant tongues, including Filipino, has already begun to alter the debate about languages in Canada. The Indigenous-languages act will change the conversation some more. As the government prepares to introduce the act, it needs to decide what balance to strike between the rights it will recognize and the services it will provide.

Marc Miller is optimistic about the linguistic future—as long as Canada is willing to accept what he calls “a change in mentality. Historically, we’ve made the mistake of approaching language as a zero-sum game. But that’s not how it’s seen in Europe. If you give value to Indigenous languages, if you give value to French in many parts of the country, if you give value to English in Quebec, we’ll all come out better.”

Niigaan Sinclair expresses a related idea in more poetic form. “If you saw part of a tree,” he says, “wouldn’t you want to see more of it? English offers you just one way to see the tree. Cree offers you another way, Ojibwe another way again. It seems Canada has always said, ‘There’s only two possible ways to see the tree.’ But aren’t there roots? Aren’t there branches?”

The Indigenous-languages act has to provide hope—but not false hope. If you thought bilingualism was tricky, welcome to our globalized, Indigenous future.