Penguin Press

Penguin PressWhy do we cook? The obvious answer—because we must eat—is less obvious than it once was. There are chefs who can marry flavours and master techniques that we can only dream of, and corporations that can consistently deliver food more cheaply and conveniently than we ever will. So, on a practical level, there are some very real arguments for not cooking.

Of course, most of us instinctively know that we lose certain things when we outsource our nutrition—nutrition itself, for one. And studies show that as we spend less time in the kitchen, we seem to spend more of our time eating, and we eat a lot more. We also spend more time watching other people cook: on television, on YouTube, and on all those supersaturated food porn blogs.

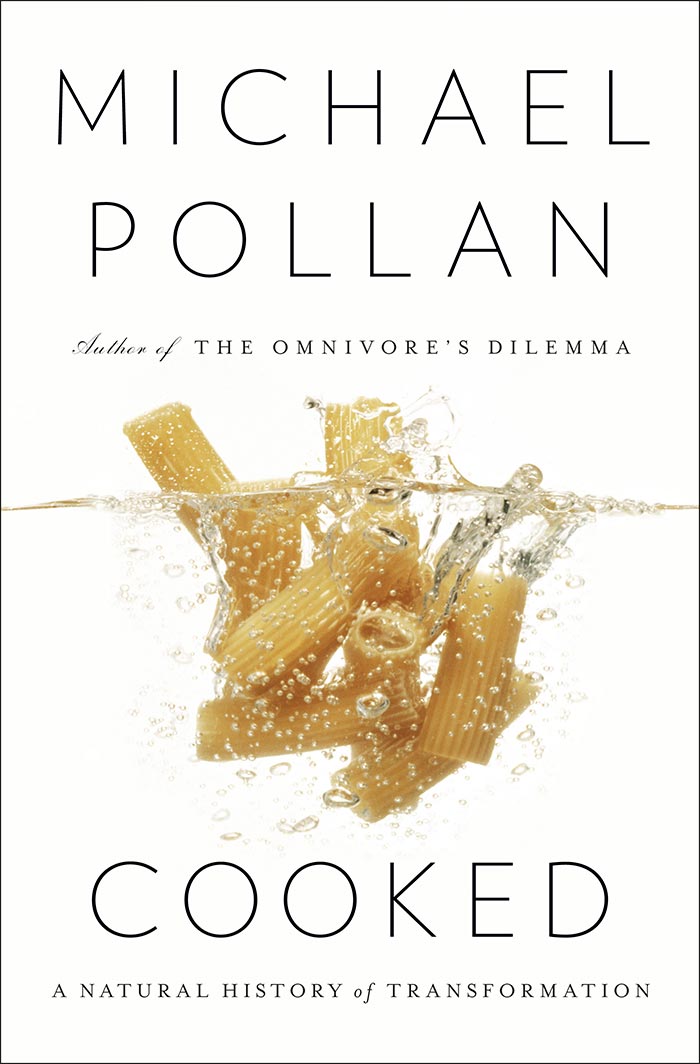

But if you’re not in the habit of reading up on changing food consumption habits, and you’ve somehow avoided reading those monthly headlines about the obesity epidemic, or if you’ve never heard of Michael Pollan—the author, most famously, of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, and now of the newly released Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation—you may wonder why it is anyone’s business whether or not the food you eat is warmed in a neat microwaveable tray or simmered messily on a stove.

Before I had children and a husband (I was going to say before I had a decent paying job, but I work for a magazine in Canada, so there really is no such thing), the arguments for cooking seemed fairly plain, and they had nothing to do with health. It was a cheap way to eat well; I could feed myself and my friends a better meal than I could afford to buy in a restaurant. I did have plans to splurge, one day: my roommates and I kept a glass jar for stray loonies and called it the Lotus Fund, after Susur Lee’s fabled first restaurant, on a desolate block of houses in downtown Toronto. But it closed before we had collected enough coin; the only thing I ever ate from Lotus were the peppery nasturtiums I pinched from the window boxes outside.

The reason I could feed myself and my friends well was because I was lucky enough to grow up with a mother who cooked for me. She did so with intention, if not outright rebellion, having grown up an orphan in her own home, with two stage actors for parents. My schoolmates loved her crispy, crumbly oatmeal cookies made with lard; her brownies made with raisins (as a concession to a cousin’s walnut allergy), not so much. Daughters of a certain age always find something excruciatingly embarrassing about their mothers; for me it was the homemade bread I had to eat. I would have done anything for “accordion bread,” as my mother scathingly called those plastic, polka-dotted bags that emanated a sweet, stale scent of soft white loaf. “Plastic cheese,” as she called Kraft Singles, were nearly as desirable. A grilled cheese sandwich made of these two ingredients, blessed with the extreme unction of Heinz ketchup—well, this to me was a holy trinity.

With my own daughters, I have tried and failed to keep up my mother’s standards. We don’t eat a three-course meal every evening, and breads and desserts are no longer a daily affair. There are too many nights when we scramble eggs for dinner, or rely on the carrot ribbon–broccoli-and-garlic pasta that my eldest daughter created when she was still in kindergarten. But the meals are almost always from scratch, and takeout is a rare affair. Although I can afford it these days, I still can’t stomach the expense-to-quality ratio it delivers.

There was, however, a dark period, when cooking for my family began to feel like drudgery. It is one thing to experiment with puff pastry or roasting geese (as I did in undergrad, when time was no luxury), or creating some gryphon-like turducken to impress your guests; it is entirely another thing to try to get dinner on the table, day in and day out, coat off and apron on, with only minutes between meltdowns and satiation.

Cooking is drudgery, sometimes. No amount of beautiful writing, simpering Food Network–hosting or elegant philosophizing on the subject can avoid this, though many honey-mouthed people do try. This is the uncomfortable fact that the good food movement is always trying to pussyfoot around.

There are two ways to gain traction, or at least street cred, within that movement:

- There are the hedonists who have found politics (because they are truly concerned about the well-being of the planet, the human race, their grandmother’s heirloom tomatoes, etc.).

- There are the political activists who have discovered that hedonism is the best way to motivate the masses (a variation on the old adage, the best way to a man’s heart is through his stomach).

Michael Pollan has always struck me as one of the latter: an activist in foodie clothing. For a decade now, he has been an exceedingly successful and persuasive leader for the food movement. He brought us the good news of organic farmers’ markets, and inspired a love-in of happy meat raised by happy farmers to be eaten by happy (and well-heeled) diners, and fomented their everlasting disgust in the ankle-deep rivers of effluent flowing from Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations. He probably also inspired the many hilarious send-ups of said people (ex. Portlandia’s “Is the chicken local?”) And yet, I’ve never thought of Pollan as a food writer; I prefer to think of him as a naturalist, curious about life and our place in it. His best book by far is The Botany of Desire, which is a natural history of the senses, and our relationship with four plants (apples, tulips, potatoes, and marijuana) that he suggests may have co-evolved with us, perhaps adapting us to their needs, as much as we adapted them to ours.

Pollan’s newest book, Cooked, confirms this impression. It is organized similarly to The Botany of Desire, this time divided into the four elements we rely on to cook or transform our food: fire, water, air, and earth. The difference is that this book is much more of a bildungsroman, if you can call a non-fiction book by a middle-aged man such a thing. Pollan is not just considering each of these elements, and their place in cooking traditions, civilizing influences, social structures, and so on: he is actually chronicling his quest in the kitchen, with experts, to learn a few cooking techniques. The section on fire considers that quintessential southern tradition, barbecue, and the section on water watches him master the braise. Air aims to bake bread with the perfect oven spring (i.e., to be well-risen), and earth considers fermentation (of vegetables for pickling, of hops for brewing).

At the outset, Pollan himself acknowledges that cooking is an obscure line of inquiry for a writer who has always been interested in how we can “acquire a deeper understanding of the natural world and our species’ particular role in it.” He goes on to observe that “Cooking has always been a part of my life”—well, good—“but more like the furniture than an object of scrutiny, much less passion.” Not exactly auspicious words from someone who is setting out to write another 400 or so pages on the subject.

At a certain point, most intelligent people within the food movement begin to realize that the only logical solution to so many of the messes we’re in right now—messes that are compromising our health, our environment, our social units, and perhaps even our happiness—is to find ways to get people to cook more, which is the primary impetus for Pollan’s book. But this is easier said than done, and most of said people would rather write about food than write recipes. The vice-president of the James Beard Foundation, Mitchell Davis, once told me that his awards program gets more and more submissions of books about food each year, and fewer and fewer books of recipes.

This may say something about which gender is in the kitchen. As more women have given up the drudgery of daily cooking, a greater number of men have taken up the gas flame, either as a form of showmanship (“Let me dazzle you with my slow-cooked pig roast that I got up at four in the morning to stoke”), or intellectualism (“Let me philosophize over the true nature of my relationship to this beast I just killed”). For lack of a better term—and indulging, perhaps, in my own brand of sexism—I have come to think of this as the male approach to cooking (typified, in my mind, by the pseudo-scientificisms of Cook’s Illustrated). Pollan touches on this in Cooked, noting that barbecue, a traditionally male concern, tends to be associated with celebration and occasion, while women tend to be associated more closely with the mundane responsibilities of getting homecooked stews and braises on the table for dinner every night.

One of the great problems of food writing is that it is attempting to convey something sensual in a medium that can only cast shadows on a cave wall: it will never rival the Platonic ideal it is representing. Pollan makes this abundantly clear in Cooked, a book that works best when he sheds the foodie storytelling that one can only imagine a well-meaning editor or advisor pushed him towards, and instead reverts to his old natural history ways. He is particularly passionate about the microbiology of food; counter-intuitively, perhaps, he is a much better read on the evolution of brewer’s yeast than he will ever be on the challenges of dressing and cooking a roast pig. His eye for intricacy is well-suited to unpacking a sophisticated scientific or cultural phenomenon, but that same talent turns a description of actual cooking into a tediously reported, many-paged affair.

It’s too bad, because Pollan’s premise is absolutely right: getting into the kitchen does solve a lot of society’s ills. But if anything, this book is more likely to turn people away from the kitchen. Like the Food Network, it may actually make cooking seem more, not less, complicated than it needs to be. Which leaves us with another problem: how do we convince ourselves and others to keep cooking, even when it does seem like drudgery? Pollan himself acknowledges the dilemma, albeit briefly: perhaps the real challenge is that most of us are cooking alone, for ourselves, and not for each other. “To eat out of the same cauldron,” remarks Pollan, “was, for the ancient Greeks, a trope for sharing the same fate: We’re all in this together.”

The power of cooking and food lies in community—something that is fundamentally at odds with the primacy of the individual in our culture. Cooking and eating is not meant to be done by one member of the family, but by many: “The common pot is always pushing against the sovereignty of individual taste,” as Pollan himself puts it. Remembering that six hands can shell a bag of peas in a matter of minutes makes cooking easier, but a lot more fun.

Related Links

“Manufacturing Taste” by Sasha Chapman (September 2012) • The (un)natural history of Kraft Dinner—a dish that has shaped not only what we eat, but also who we are

“A Matter of Taste” by Sasha Chapman (March 2012) • Mitchell Davis, vice-president of the James Beard Foundation, believes you can’t develop a national cuisine until you create a public conversation about food