In 1999, Sanjeev Yogeswaran came to Canada as a refugee. He was fourteen years old, and his family had paid almost $40,000 to get him out of Sri Lanka, which was gripped by civil war. At age fifteen, he began working at Pizza Hut; within a few years, he was working at three Pizza Huts at the same time, putting in seventy hours a week. Except for a brief period when he co-owned a pub, Yogeswaran has spent the vast majority of his restaurant career working for other people. And then the pandemic hit.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

It was the last weekend in March. The business Yogeswaran managed was closed; two weeks without going in to work was the longest vacation he’d had in two decades. His sister, Mirna, a financial manager, had been casually catering for years, cooking for friends’ birthday parties and the like. The siblings discussed posting a small selection of dishes for sale, which they would deliver themselves to the areas near their homes, in the suburban Ajax and Pickering areas. With little planning—just that quick conversation—they shared a menu on WhatsApp, telling family and friends that they were offering kochikadai biryani (a rice dish in which a basic dough is used to seal the pot lid so no steam escapes), chicken fried rice with devil chicken (fried chicken chunks tossed in vinegar, soy, sweet sauce with peppers, onions, and chilies), and yellow rice with mutton curry. Within half an hour, Yogeswaran recalls, they started getting orders. “We hadn’t started cooking.”

Cooking out of Yogeswaran’s home, they delivered twenty orders that Saturday. Then they started promoting the food on Instagram and adding more dishes. By the third week, they were packing 100 orders and making lamprais: rice with mutton curry, eggplant moju (pickle), fish croquette, boiled egg, and blachan (a chili shrimp paste), all bundled in a banana leaf—a lot of work, but perfect for delivery because the leaf helps maintain the heat and moisture. They rented a commercial kitchen from 4 a.m. to 9 a.m., when it would otherwise have been closed, and hired one of Yogeswaran’s laid-off cooks. During their busiest time, they were cooking and delivering five days a week: requests from customers in nearby municipalities had prompted them to schedule drop-offs in parking lots with one-hour windows for pickup. Yogeswaran is now looking for a bricks-and-mortar location to launch a post-quarantine business.

In the year or two before covid-19 shut the restaurant industry down, articles started popping up about so-called ghost kitchens, which offer full menus via delivery but no restaurant you can walk into and eat at in person. Back then, discussions about the emerging phenomenon focused on the potential for restaurants to expand their reach without the cost of dining space or front of house staff—a far cry from landing on them as a creative dining solution to a worldwide public health crisis. What the Yogeswarans had done neatly encapsulates how many industry observers describe the current climate: changes to the sector that had been predicted to unfold over years have been accelerated to a matter of weeks.

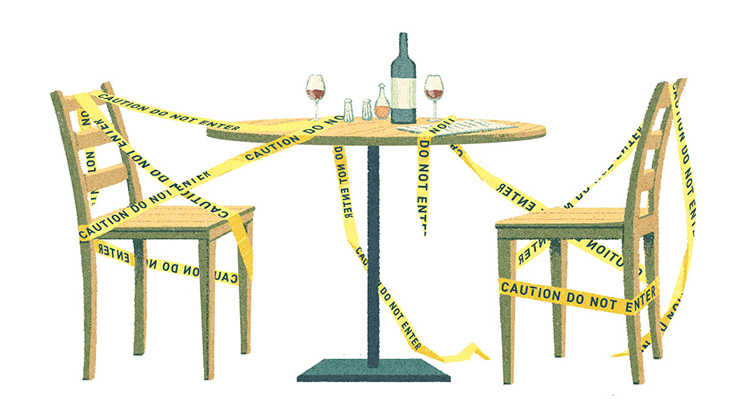

Around the world, we’re seeing indications of what dining will look like during what you might call the in-between phase of covid-19: after restrictions have eased but before we have a vaccine. In Hong Kong, they’re taking your temperature when you arrive. In some restaurants in Berlin, you scan a QR code on your table for contact-tracing, so the business can track you down if there’s an outbreak linked to the premises. Some restaurants in Taiwan are using plastic dividers to separate diners. In Melbourne, restaurants are offering limited menus and requiring payment in advance. A three- Michelin-starred restaurant in Virginia experimented with poshly dressed mannequins to make the socially distanced dining room feel less empty—because, as any restaurateur will tell you, not only are they unable to make money with a half-empty dining room, their customers don’t want to eat in a half-empty room.

Food-and-hospitality services in Canada employ 1.2 million people, and the sector’s revenue of about $90 billion represents an estimated 5 percent of our gdp. When independent restaurants fail at the scale now being predicted—as many as 85 percent, according to a report commissioned by the Independent Restaurant Coalition, a US counterpart to Canada’s Save Hospitality, an alliance of independent restaurateurs formed in response to covid-19—they don’t just take down their owners but their employees, suppliers, farmers, and landlords, along with the value of commercial rent and adjacent residential real estate. Because how much is your house really worth in that trendy neighbourhood, the one with all the cool places to eat and drink, when half those places are boarded up? Restaurants are a load-bearing pillar of our culture and economy.

It’s too early to know the full breadth of what a post-vaccine restaurant landscape will look like. But, in the current liminal era, a few patterns are starting to emerge. Size matters. Flexibility is essential. And those who have the loyalty of their communities and are willing to try any and everything—like the Manhattan restaurateur who told me she considered transforming her shuttered dining room into a temporary daycare for friends—will be the survivors. Many other chefs, owners, cooks, and servers, and the restaurants they orbit, will not be so fortunate.

Back in March, as it became apparent that covid-19 was about to break out in earnest across North America, many restaurateurs attempted to calm their customers, assuaging health concerns with social media posts promising their commitment to hygiene and customer safety. Behind the scenes, they were panicking. And, by the middle of the month, they started closing. Some cite the shuttering of restaurants in France as the first sign of what was ahead, others the suspension of the nba season or Tom Hanks testing positive. Some wanted to close earlier, believing there was a moral and public health obligation, but were waiting for an order from any level of government—an edict they could use to justify the closure to their staff, landlords, and creditors.

Some chose to do takeout and delivery, at a fraction of their usual revenue. Some talked to their lawyers about suing their insurance providers for rejecting their business-interruption claims. All of them were trying to figure out what to do with the contents of their fridges: often tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of perishable ingredients. Many gave them away to staff or food banks.

It sounds heartwarming—restaurateurs sharing their last loaves of bread and cases of fruit. And the intentions were certainly good. But it was hardly uncomplicated. The restaurants owed their suppliers for those foodstuffs, and their suppliers owed their farm producers, and independent farmers are not known for being flush with cash.

Restaurants pay for their food on credit, typically with terms of about thirty days: when restaurants closed in mid-March, many were preparing to settle bills for food they had bought a month prior. With revenue reduced to zero, how were they going to pay for the inventory they just gave away? “Ideally you should have three months of reserves that can cover you for all expenses, including payroll,” says Arturo Anhalt, who owns several Toronto restaurants, including Milagro and Dirty Bird. “I studied this in hotel-management school.” That’s the theory. In reality, few restaurants have that kind of cash reserve.

“The economic disruption doesn’t end there,” says John Sinopoli, a Toronto restaurateur who helped organize Save Hospitality. “My suppliers have called me and said, ‘If more than 30 percent of you go bankrupt, we’re done. We can’t absorb all the receivables. You guys owe us too much money. We can’t write that off.’”

It’s hard to imagine the average outsider having strong views about the fixed costs or monthly payroll expenses involved in furniture manufacturing or dentistry. But it’s fairly common for people, whether or not they have any hospitality experience, to tell me that a restaurant dish is overpriced or what percentage of the business’s revenue should be coming from alcohol sales.

These assumptions come to us naturally: our familiarity with retail food and alcohol costs enables us to imagine that we understand restaurant food pricing. We see a plate of chicken and compare it to what we pay for chicken at the store, omitting the labour involved in ordering, receiving, stocking, and paying invoices for the chicken; in trimming, brining, storing, rinsing, and soaking it in buttermilk; in flour-coating, frying, and packaging or plating with waffles, hot sauce, and other ingredients, which are also not free. Additionally omitted: the price of commercial real estate, insurance, utilities, credit card fees, marketing, hvac maintenance, grease-trap cleaning, training, and breakage. (This list is not exhaustive.)

Similarly, it’s easy for the layperson to assume that the proliferation of delivery apps has created a new revenue stream for restaurants, one that comes with less overhead—no extra square footage to rent and no servers to pay. But, while the tech companies that have made delivery so ubiquitous have done a good job promoting themselves as friends of the restaurant industry, they take exorbitant commissions—on average, about 30 percent—and the economic results for restaurants are mixed. (Mike von Massow, a professor in the University of Guelph’s Department of Food, Agricultural and Resource Economics, sums up the problem with what he tells me is an old business-school joke: “A manager tells the boss there’s good news and bad. The bad news is we’re losing money on every unit. The good news is that sales are up.”) All of these costs come amid rising prices for everything—food, labour, rent—and growing public pressure to pay staff fairly, provide benefits, use better ingredients, and support sustainable food systems.

What all of these factors add up to is this: 95.8 percent of revenue for Canadian restaurants goes to covering their costs, according to national nonprofit Restaurants Canada. A restaurant owner who sells $1 million of food and drinks will clear $42,000 for herself after paying all her bills. That makes it hard to save for a rainy day.

These stresses are part of running a restaurant in good times. And, in those times, we can afford to perceive restaurants as small, one-off businesses to which we have specific, personal attachments. But these are not good times, and the future of restaurants isn’t just about restaurants alone, a weepy tale about the local bistro that we hope stays in business because they always remember our drink order.

Sinopoli says that the politicians he’s spoken to at all three levels of government, while they want to help, have no idea how to. And, in addition to the sector’s low profit margins and inherent fragility, that’s another challenge that restaurants face in this moment: not only does the public not understand how they work, neither does the government.

Idon’t think I ever heard the word hospitality,” says Diana Rivera, senior economist at the Brookfield Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, of her many years of academic study. “My instinct is that feeds into the federal response. If there is less research about it, then there is less information as to how they might act.”

“Business schools tend to focus on export-oriented industries,” explains Mike Moffatt, a professor of public policy at Western University. “That doesn’t dovetail well into restaurants. I think, in general, it’s the devaluation of work done by women. Most economists are male. If you look at the industries we tend to focus our attention on, they tend to be oil, gas, and manufacturing—industries that are nearly 80 percent male.

“One other reason is we tend to focus on what you’d almost call ‘anchor tenants’ in a retail sense. If you’ve got a city that’s creating a lot of jobs in the tech sector or things like that, that will sort of automatically create a bunch of restaurants. So the idea is that a restaurant is not going to create an auto assembler, but having an auto assembler move to your city is probably going to create a bunch of restaurants.” And thus we have a great many economists who can advise the government on matters pertaining to the automotive sector and comparably fewer who are equipped to devise policy for restaurants: if business schools produce economists who don’t value or understand the hospitality industry, and the government hires graduates from those schools to advise it, it’s no wonder that a restaurant-specific support strategy eludes us.

This gap at the academic level may explain the government’s failure to put forth an industry-specific plan for hospitality. The supports it has offered to small businesses more broadly are also of limited help. Loans of $40,000 may perhaps help a small shop owner who didn’t have to throw away their entire inventory, but they’re far less effective when a restaurateur uses a chunk of it to simply pay their debt on goods they never sold. And wage subsidies that require an employer to still pay 25 percent are untenable when revenue drops to zero and, as one restaurateur told me, your weekly payroll is $70,000.

Save Hospitality has outlined several proposals for assistance that is more customized to the industry. They include: forgivable loans intended to cover shutdown losses and reopening costs, the cessation of commercial property taxes, a requirement that insurance companies honour business-interruption claims, and a reduction of taxes on spirits. There has been no official government response to the proposals.

For restaurants that have kept operating during the quarantine, even partially, it’s been an uphill battle. Early in the pandemic, Iori Kataoka’s Vancouver restaurant, Yuwa Japanese Cuisine, shifted to producing food for takeout. It’s a compromise: items like Yuwa’s griddle-cooked Wagyu loin steak, the luxuriously fatty beef served on a sizzling platter with sauce made from sake lees (a yeast byproduct of the fermentation process), cannot be stuffed into a takeout container. “And you may think sushi is fine,” says Kataoka. “Not really.” Sushi rice should be human-skin temperature. It hardens as it cools. Unless fish is cut fresh, it leaks moisture. “Completely different experience.” But, early on, Kataoka found that most of her staff already owned a couple of packages of masks at home. So she pivoted quickly. With just a few employees in the kitchen and Kataoka doing deliveries herself, she was averaging about 30 percent of her previous revenue at first—by July, it was about 55 percent.

“There is a Japanese saying,” says Kataoka. “‘Act as if you are grasping the straw to climb up the mountain.’ That’s what I’m feeling. You don’t have anything to hold. It may break any time. But you have no choice. You have to climb up.”

The reality is that many restaurants will never reopen. Until a vaccine is created and distributed, those that do will be facing ever-changing COVID-19 outbreaks, capacity limitations, and a recession. Industry analysts expect that restaurants in our postpandemic world will be smaller in a number of ways. “We’ll definitely see [fewer] bricks-and-mortar locations,” says Robert Carter, industry adviser for Straton Hunter, a hospitality-consultant group. “Even the ones we do see will have smaller footprints.” He envisions underperforming independents closing, with chains taking advantage of a reduction in rents to expand their locations. Large restaurant companies have access to capital along with departments dedicated to strategic planning, marketing, and other business development; in a time of flux, this can be a great advantage. Smaller restaurants share a bond with their customers and have loyalty in their communities that chains often do not, but they’ve traditionally been too lean to plan for emergencies and have little in the way of savings.

Constrained by those parameters, what will restaurants in the latter group do to boost their odds of survival? We’ve seen chefs performing tutorials on Instagram, dining spaces repurposed to package food for takeout and meal kits, restaurants turned into grocery stores. These initiatives are important in the short term, for increasing cash flow and maintaining a connection to customers, but they have their limits.

“Diversification gives some insurance against uncertainty,” says von Massow, the University of Guelph economist. “But only if it doesn’t cannibalize the core business. [Restaurants] shouldn’t try to be all things to all people.”

Though many restaurants began selling groceries in addition to cooked food in response to the pandemic, most can’t make money on that model in the long term. As dining service resumes, the storage room it requires will eat up too much precious square footage and fridge space. And, as safety concerns about returning to grocery stores wane, most people won’t be willing to shop at restaurants anyway. If a restaurant can execute additional services, such as making meal kits, which increase business volume during otherwise quiet hours, that will help, says von Massow. But, if they pull volume out of the kitchen during peak hours, then it’s a competitive service rather than a complementary one.

As delivery continues to be a larger focus, some restaurants will have to change their physical spaces, shrinking dining rooms and expanding kitchens. Carter also predicts that more will shift to providing their own delivery to avoid exorbitant app-based fees—a new challenge for independents whose core competency is cooking and service. On the upside, says von Massow, “it may deal with some of the issues we’ve had with [that] delivery model: cold food, control, distance, which foods get delivered.”

Self-delivery is also going to make ordering more expensive. The third-party app-based “disruptor” version of this service comes at the expense of its couriers, who are exploited by virtue of being independent contractors, and is subsidized by the venture capital that gets poured into the tech industry. When restaurants have to pay standardized wages to people delivering food, those costs will have to be passed on to the diner.

Overall, von Massow and other industry analysts believe that restaurant eating will need to become more expensive. “We will eat out less, but we’ll have to get more out of the experience,” he says. “I’m not sure we have a sense of the elasticity of restaurant demand yields. It probably varies by type of restaurant.” Elasticity is the measure of how much consumer demand changes based on price fluctuations: it’s why demand goes down when prices go up. Given that supply—the number of tables in a restaurant, which will need to be spaced out to allow for physical distancing—is going down, von Massow suspects we’ll soon learn more about this no-longer-academic question.

If there are only half as many seats available, let’s say, how much will a restaurateur be able to increase her prices before customers start to balk and those tables go empty anyway? An extra 10 percent? For the people who scramble for reservations at the latest hot spot, probably. For many of us who have been cooped up for months and are desperate for a sense of normalcy, maybe. An extra 100 percent? We have no idea.

People eat out for a lot of reasons. One of them is to feel like a part of something: the unique intoxication of a room full of strangers eating, drinking, laughing, and flirting. It’s the difference between seeing a really funny comedy in a theatre full of people and watching it on your laptop, alone. The best restaurateurs are magicians, and the environments they conjure are as much stagecraft as cooking. That’s the part, perhaps even more than the nuances of the food on the plate, that all the takeout and delivery in the world cannot replicate—and we’re about to find out just how much that part matters. How much is a restaurant experience really worth?

Answering that question may involve ideas that were previously almost unthinkable in the industry, such as demand, or dynamic, pricing. Embraced long ago by airlines, hotels, and car-rental agencies, dynamic pricing is the practice of adjusting what you charge based on fluctuating demand—it’s why it costs more to fly on weekends than mid-week. The only Canadian restaurateur I know who has tried this is Roger Yang, who recalibrated the cost of the tasting menu at a restaurant he had couple of years ago: a little bit less from Sunday to Thursday and a little more on Friday and Saturday. (The goal back then was not to increase revenue but to more evenly distribute it, along with labour, over the week.) Because he won’t be able to safely fill all the seats at his restaurants on weekends now, he thinks he’ll probably use this model again over the next while. Other restaurants that won’t or can’t shift a significant portion of their revenue away from dine-in service may find themselves inclined to do the same.

What’s far less clear is whether and how the pandemic and its aftermath will affect the third rail of restaurant politics: wages and tipping. Some restaurateurs think that the preexisting pressure to improve payment for servers and kitchen staff, combined with the constraints of dining in this in-between, pre-vaccine time—needing to space tables out means fewer diners, and fewer diners means fewer tips—make the choice clear. “Everybody is starting to rethink their business,” says Amanda Cohen, chef-owner of New York’s Dirt Candy, which eliminated tipping in favour of a service charge in 2015.

“Everybody is having this big come-to-Jesus moment. . . . The way we run our restaurants just left everybody so vulnerable, including ourselves—because we don’t charge enough for food and we don’t pay our employees more. And, when the shit hits the fan, we’re all about to lose our restaurants. And we all willingly participated in this.” She predicts that “there will be a much stronger movement to get rid of tipping” and to increase wages “across the board.”

Amanda Peticca-Harris wants to believe this is true. Before Peticca-Harris was a professor at the Grenoble School of Management, in France, she managed restaurants in Canada. The business professor in her says, Yes, there’s an opportunity for a no-tipping movement. But her first-hand knowledge of the industry leaves her far more skeptical. “covid-19 isn’t going to be the time that they go, ‘I’ve just had this epiphany. Let me innovate with no tipping.’ They’re going to draw those purse strings even closer because they’re going to be scared.” Peticca-Harris believes that the period of economic uncertainty could, instead, prompt a cycle of exploitation. “That’s a bad climate for employees and employee rights. ‘I’m grateful to have this job,’ as a mantra, can be a bit of a dangerous terrain.”

Not everyone was unprepared. While the majority of restaurateurs scrambled to cope with the seismic shock to their system, some had the resources to weather or adapt to the storm. Richmond Station, in Toronto’s financial core, has been busy since it opened in 2012. As is usually the case with a successful restaurant, diners and interviewers constantly asked when the proprietors were going to open another location (perhaps a bit more so in this case because Richmond Station was founded by chef-owner Carl Heinrich just after he won Top Chef Canada). But, because Heinrich and his partners have resisted the common urge to expand, and because they’re operating their restaurant with no debt, he thinks they’re in a good position to get through.

Many wildly successful chef-driven restaurants have had to shutter locations recently—not because the businesses weren’t profitable but because they don’t have the cash reserves to sustain a long closure. Momofuku has permanently closed two of its locations (Nishi, in New York, and ccdc, in Washington) while Portland’s Pok Pok has permanently closed four of its six locations, the owner citing the carrying costs of so many businesses as a factor.

Staying small is one protective mechanism, it turns out. Old fashioned innovation is another. Five years ago, just a few blocks away from Richmond Station, Colin Li began taking over the restaurant his parents had opened in 1997. It was difficult at first: he remembers his parents resenting his insistence on shortening Hong Shing’s menu of 200 dishes. But, gradually, Li managed to court a new audience with an updated menu and modern social media strategy while maintaining existing clientele by holding on to key dishes and cooking methods. And then, a year ago, Li began developing an online ordering system. The problem with the delivery-app companies wasn’t just their commissions, Li believed, but their control of customer data.

In a stroke of good fortune, Li launched his ordering platform two weeks before everything went haywire: without intending to, he had spent the past year preparing for a pandemic. On the back end, the new ordering system gave him the ability to see which web pages his customers were coming from (like via Instagram or through a Google search), how much time they were spending on his website, where on the page they were stopping, and where they were clicking. Using information like this, he can automatically target customers by, for example, sending them an email encouraging them to try a dish he already knows they’ve been eyeing. Seeing Chinese restaurants close all over the suburbs, Li launched a social media campaign asking people where they wanted him to deliver; he would go to wherever there were the most requests.

Most customers have become used to making food choices at the last minute: what they want, when they want. Changing this kind of consumer behaviour is hard. But quarantine, isolation, and public health guidelines upended so much of our behaviour overnight that they also created opportunities—and those are what enabled Li to redefine this relationship with diners to the point where they will order dinner days in advance.

A more ephemeral but no less significant obstacle to recovery is the language we use to describe the times we’re in—how we use words like recovery in the first place. Calling our current phase of covid-19—not quite shut, not quite open—a “restart” or a “reopening,” as many governments and establishments are, underplays just how big and long-lasting the challenges are. “I think that’s entirely the wrong term,” says Moffatt, who worries that language like this makes the process seem easier than it is. The looming discontinuation of government support, as opposed to an alternative strategy that includes longterm investment in retraining and jobs programs, reflects the problems with thinking of something as a “restart.”

“I think it matters very much what we call anything,” says the Brookfield Institute’s Rivera, urging language that prioritizes this as a transitional, gradual stage, one that is likely to have setbacks. The danger of “reopening” language, says Rivera, is that restaurants will be operating at very difficult margins—maybe at a loss, maybe breaking even if they’re lucky. And, with simplistic terminology, there will be less public awareness of those risks and struggles and, therefore, the possibility of a too-fast withdrawal of government support. “That adds up to a huge macroeconomic risk.” If policy makers don’t recognize the transitional, gradual nature of this recovery, we could see another wave of closures and job losses: restaurants that used savings, savviness, and government help to survive the quarantine period only to reach insolvency when they reopen, but just partially.

One fragile thread to guide us up a mountain. When I check back with Kataoka, a while after our first conversation, she offers up a new saying: “A drowning man will catch a straw.” We may yet find that there is more truth to that than we’d hoped.