It’s 9 a.m. and the coffee’s on at the Bayers Westwood Family Resource Centre. The narrow, two-storey building is nestled in the middle of a public housing project in the west end of Halifax. The front door opens into a crowded sitting room.

A number of single parents have come for the cooking classes and are dropping off their kids at the free child-minding service. Other people are here for company. But a larger group is looking for something they struggle to find on their own: a bite to eat. One of the centre’s main draws is a small counter where coffee, tea, and a plate of day-old muffins and bagels are served—regular donations from the charity Feed Nova Scotia. Across the hall is the Trading Post, a small room stocked with packaged foods clients have received from their local food bank but that they can’t, or don’t, use: cans of Campbell’s soup, Aylmer diced tomatoes, Heinz baked beans, and Zoodles line the floor-to-ceiling shelves.

Not all of it is nutritious. Everyone understands that. But it’s something. And when you have a community to feed, you do what you can. The predicament weighs on the centre’s hands-on, energetic executive director, Donna Sutton. “People come in the morning for a bagel and coffee,” Sutton says. “They come back in the afternoon for a muffin. That’s breakfast and lunch. Then they just have to worry about dinner.” With meager earnings and no access to credit, many of Sutton’s clients are facing cold truths. Some weeks, stopping off at Sobeys means there might not be enough left to buy medication or pay rent or put gas in the car to get to work. Because groceries are often the only flexible item in a tight budget, they are what families tend to sacrifice first. Families that have to make these kinds of trade-offs are called food insecure.

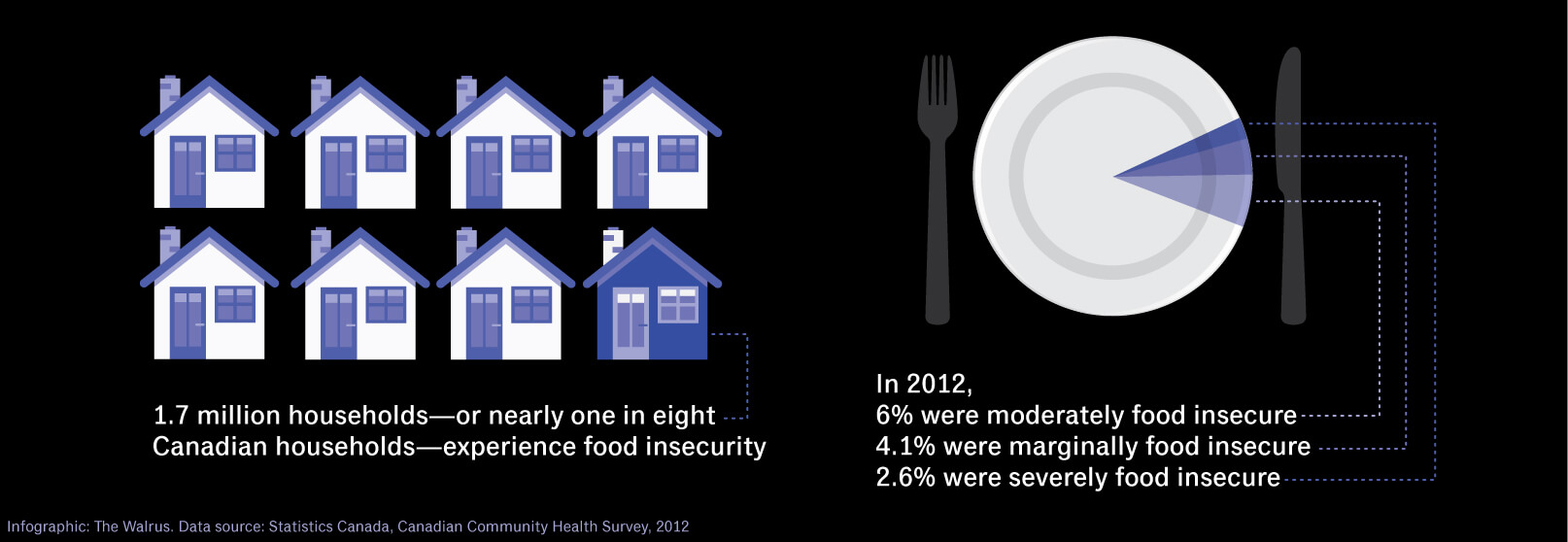

Food insecurity is largely about the struggle to afford food. Insufficient social assistance, increases in the number of low-wage, part-time, or contract jobs, and a lack of affordable housing have created financial constraints that make it more and more difficult to eat. Proof, a food-insecurity research group at the University of Toronto, breaks down the problem a few ways. Worrying that you’ll run out of provisions before you manage to buy more is “marginally food insecure.” According to Proof’s analysis of the most recent nationwide data from Statistics Canada, about 580,000 households fell into that category in 2012. If you compromise on the quality or quantity of your portions, you’re “moderately food insecure.” That category includes 786,100 households. Another 336,700 are severely food insecure—that means they skip meals or spend days without eating. All this adds up to 1.7 million households, which translates to nearly 4 million Canadians. That’s a conservative estimate, because some provinces and territories can, and have, opted out of more recent StatsCan surveys. The surveys also miss the most at risk: incarcerated people, remote rural residents, people living on-reserve, the homeless.

It also seems to be getting worse. Comprehensive data has only been available since 2007, when national monitoring began, but even in that short period, the overall proportion of households that are moderately or severely food insecure increased from 7.7 percent in 2007 to 8.3 percent in 2012. Hunger may be linked in the popular imagination with images of destitution, but the food insecure can include restaurant staff, delivery drivers, cashiers, and janitors. They are our coworkers, our neighbours, our relatives.

Lower-income populations are affected more than others: recent immigrants, people of colour, single mothers. Children are especially vulnerable—one in six live in food-insecure households. The problem of hunger is also urgent on postsecondary campuses. Meal Exchange, a non-profit aimed at tackling food insecurity at Canadian universities, published the results of a study in 2016 that showed half of all students “had to sacrifice buying healthy food” in order to pay for books, tuition, or rent. Affected groups will likely have a tougher time in 2019. Canada’s Food Price Report, produced annually by Dalhousie University and the University of Guelph, predicts grocery bills this year could spike by 3.5 percent—with the price of vegetables jumping as much as 6 percent. For a Canadian family of four that spends $223 a week on groceries, the higher cost will mean coming up with an extra $33 a month to keep eating the same way. The price increase will likely put the new, healthier recommendations from the updated Canada’s Food Guide (more plants, less sugar, less saturated fat) further out of reach as household diets are forced to shift even more dramatically toward cheaper, shelf-stable, processed options—foods with little or no real flavour or nutritional value.

Everyone in Canada will end up paying a price, whether they live in a food-insecure household or not. A 2018 study estimated that the economic burden of Canadians failing to meet healthy eating recommendations is roughly $13.8 billion per year—$5.1 billion of which is directly related to health care spending, and the rest is linked to factors that include lost productivity. The food insecure are at greater risk of chronic, diet-related conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease. Health care costs are also between 23 and 121 percent higher in households that struggle to access nutritious food, with costs climbing alongside the extent of the deprivation experienced. Food insecurity is a drain on mental-health resources as well. A 2018 Canadian study showed that the proportion of severely food-insecure adults receiving treatment over the past year for conditions that included anxiety, depression, mood disorders, and suicidal thoughts was more than double that of adults who had enough to eat.

Programs like welfare, family allowance, and employment insurance were introduced, in part, to help alleviate the consequences of being food insecure. But social assistance is no longer up to the task. During the 1970s in Toronto, one in ten people lived in poverty. Today, it’s one in five. Vancouver Neighbourhood Food Networks, a collective focused on tracking food security in the city, calculated last year that if the average rent for Vancouver low-income housing ($687 per month) is subtracted from the monthly welfare rate for a single adult ($710), only $23 remains. In other words, a person on income assistance has less than a dollar per day to spend on food. It’s not hard to imagine that, as economic trends continue to chip away at stable, long-term employment, food insecurity will soon overwhelm existing social assistance programs. What Canadians need is a food policy that can ensure an adequate standard of living to offset the biggest effect of those economic disruptions: hunger.

Food-security and antipoverty advocates have been working with the federal government to develop such a policy—one that recognizes adequate food as a human right, much like water or clean air. But lack of political will means little progress has been made. The country has ratified numerous international agreements affirming the right to food, and an Action Plan for Food Security was proposed in 1998. But hardly anything from it has been executed. The inaction underscores that Canada has never really strategically addressed hunger as a national issue and has never appreciated food insecurity as a reality within its borders. Instead, we have off-loaded the job of feeding our citizens to food banks, soup kitchens, and charitable efforts such as the Bayers Westwood Family Resource Centre.

With nearly 20 percent of its population affected, Halifax has the highest rate of food insecurity among Canadian cities. Some contributing factors are unique to the area: high student numbers, an influx of job seekers from Cape Breton, and nearby rural areas gutted by the shift from small-scale farming to agribusiness and by the decline of industries like coal and steel. But the city is also a bellwether for many changes taking hold across the country, such as the advent of so-called precarious work, which has increased in Canada by 50 percent in the past two decades, and rising housing costs. The jobs Halifax offers are mostly service-sector gigs—often short-term or contract work without benefits or security. About one in three Haligonians lives in rented housing, with 43 percent putting a third or more of their earnings toward rent. All this influences what residents eat or whether they can eat at all.

“I can’t afford breakfast,” says John Hemr, who lives in the Bayers Westwood housing project. He is sixty-six, and with his red shirt, hazel eyes, belly, and greying beard, looks a bit like a hard-luck Santa. Before receiving old-age pension last year, he lived on a $600 monthly disability cheque from an accident on the job thirty years ago, when he worked as a TV repairman. His arms were elbow deep in the back of a set he was fixing when his colleague plugged in the wrong cord, and Hemr was blown back, electrocuted. It took him months to recover, and ever since, his legs go numb if he does too much activity or lifts even a few pounds.

As a single man without children, Hemr doesn’t qualify for extra help, like a child tax benefit. One brother gives him a few bucks now and then. Even with his subsidized rent of $175, Hemr’s monthly income disappears quickly. He spends $70 on electricity, $70 on a phone plan, and $100 on high-blood-pressure medication. Last year, Hemr spent $100 a month on cigarettes. He smokes to help himself relax but mostly to curb his appetite. “I tried quitting cold turkey,” he explains. “But my grocery bills were too high, and I gained thirty pounds.”

His budget left about $20 a week for groceries, depending on the season. “People look at me and think, ‘You’re a big guy. You’re healthy,'” says Hemr. “No. I’m unhealthy. To be healthy, I have to eat three meals a day. I get one meal a day.” Usually, that’s pasta, white rice, or potatoes, sometimes with a can of soup or a side of packaged breakfast sausages.

Food insecurity can be a hidden problem. “You don’t have to look hungry to be hungry,” says Catherine L. Mah, a researcher with Proof who teaches at Dalhousie University. Nor is it restricted to the unemployed. According to the data, over 60 percent of the food insecure across Canada actually earn wages. It’s just that the money isn’t enough to pay for food. Luckily, there’s usually some way to get by: a sale on pasta at the local grocery store, a meal at a soup kitchen, a food hamper, a school breakfast program, or a relative’s kitchen. But it’s “the getting by” that’s exhausting. “Food insecurity wears you down because you must constantly cope and manage,” says Mah. How people cope and manage—what the individual compromises look like week to week—may vary, but the struggle remains the same whether you’re in Halifax, Montreal, or Saskatoon.

Margaret* is a cashier in Toronto for one of the country’s biggest grocery chains. She makes minimum wage and works part time. She wants to move to full-time employment, which would automatically qualify her for benefits, but she can never manage to get enough hours. (One of her colleagues suspects the company intentionally hires more people than it needs and hands out part-time schedules to avoid paying for benefits). Margaret is one of more than 850,000 Canadians who are “involuntary part timers”—a group that has become a distressingly prominent fixture in an economy that keeps shedding full-time positions. Margaret also belongs to the hidden hungry—the working poor whose refrigerators are often empty. Because she tries to prioritize eating well, she subsists on strictly rationed portions of fruit, vegetables, and milk. She consumes a cup of soup twice a day. A salad is a single leaf. “My lettuce is four dollars a head,” says Margaret. “I have to make it last.” She’ll snack on an apple for hours or peck at 500 grams of cheddar for two weeks. “I feel hungry all the time,” she says. “And I always wonder how I will make it to the next paycheque.”

Famished while surrounded by abundant food, Margaret’s predicament highlights how proximity to fresh vegetables and fruit won’t change anything for someone with little means to procure them. When the University of Winnipeg’s Institute of Urban Studies mapped the socioeconomic conditions around seventy-three supermarkets in the city in 2016, it found that, for 60,000 inner-city Winnipeggers, healthy food was within easy reach but was unattainable financially. Low-income residents, in other words, weren’t necessarily living in food deserts, defined as communities underserved by affordable grocery stores within walking distance. Nor was it a problem of food swamps, which are areas dominated by fast-food outlets.

What the study identified were food mirages—a relatively new classification that food-insecurity researchers believe can provide a fuller picture of the crisis. Partly a side effect of gentrification, food mirages give the illusion of access to affordable nutritional options. This entrenches a two-tier food system—one for the middle and upper classes and another for the rest. It also reinforces the misconception that eating poorly is a matter of choice or a result of bad habits. But, “as it turns out,” wrote Jino Distasio, who worked on the University of Winnipeg study, “far too many live close enough to see through the windows of grocery stores but are forced to walk by en route to the nearest food bank.”

“Our hopes and dreams are that this place didn’t have to exist,” says Kimberly McPherson, a coordinator at Cape Breton’s Glace Bay Food Bank, which she says has many repeat customers, including some whose parents, and even grandparents, used to come. At the time we spoke, McPherson and her mother-in-law, Sandra (who has since retired), split a $23,000 provincial grant as their salary and occasionally ate at the soup kitchen themselves. “You want to help the poor in the community,” says McPherson. “But when you’re all poor, it’s really hard.”

Once a thriving blue-collar town, Glace Bay was hollowed out as the economy shifted in the 1980s—three mines and a steel plant closed—and fish stocks dwindled. It lost its town status in 1995 and combined with Sydney and five other towns. The community now has a population of 17,500. Today, the unemployment rate for all of Cape Breton is 15 percent—up 1 percent from last year and more than twice that of the provincial average. The food bank’s kitchen serves 1,200 meals per month. On any given day, nearly ninety people show up. Some bring a meal home to a family member. “The younger generations go out west to work,” says McPherson. “The elderly and the poor stay behind. The food bank keeps getting busier. If it weren’t here, people would be stealing food.”

Mary Makiuk is a regular. A forty-seven-year-old Inuk woman from Kuujjuaq, Quebec, she settled in Glace Bay seven years ago with her husband, who has a disability, and four of her children, aged twelve to twenty-one. Makiuk tells me she gets $1,500 a month in social assistance, including a child benefit for her two children who are still under eighteen. She has no car and takes a thirty-minute bus ride to Sydney to go grocery shopping. Food costs leave her with $300 at the end of the month. Mark Leblanc would drop by the soup kitchen as well. The father of a two-and-a-half-year-old boy, he usually eats one meal a day. Leblanc says the experience of spending time in prison several years ago for petty theft forced him to adapt his eating habits. “I don’t feel that I’m restricting my calorie intake, but I am.” On occasion, he spends most of his grocery budget on food for his son.

The Glace Bay Food Bank works with local farmers and grocery stores to secure donations, which are a tax break for the businesses. But the food bank is also an example of how some charities have adapted to the scale of the problem by become more ambitious and innovative. Along with serving meals, McPherson helps provide a basic breakfast of cereal, milk, and fresh fruit to many Cape Breton schools—part of a provincial program that feeds 12,500 students. It’s a much-needed program in the city, where the child poverty rate hovers around 35 percent. Five years ago, McPherson decided to take matters into her own hands and teach her clients—many of whom are second-generation welfare recipients—to garden. “What’s happened in Cape Breton is we don’t garden anymore,” McPherson says. “We always had gardens. We weren’t well off, but we were always well fed.” She found someone willing to donate plants and seeds, and she organized pickling sessions, showing clients how to make chow chow, a local relish made with green tomatoes. Jars of it lined the shelves of the food bank’s basement pantry last November, set to be packed in Christmas hampers.

Community gardens have grown in popularity as a way to alleviate food insecurity. To date, Toronto has about 238 of them, Vancouver over 110, and Ottawa at least 100. Alvero Wiggins, born and raised in Halifax, spent years working two jobs and raising his son. He often ate one meal a day, usually an egg sandwich, at his job in a café. The other option was cheap takeout—a pizza slice for dinner, for example. “Healthy food seemed like a privilege I didn’t have time to think about or a right to eat,” he says. His low income and busy schedule made it difficult to buy and cook balanced meals. In 2012, he became a coordinator of an urban gardening program for high-needs youth, called Hope Blooms, which today oversees seventy-two gardens that it converted from vacant lots donated by the city eleven years ago. Each month, Hope Blooms uses its own produce to prepare and distribute hundreds of free meals to families in the area. The fresh herbs are also used to make a variety of salad dressings sold through local vendors; profits are rolled back into the program and into scholarships. Wiggins today works at a violence-prevention and harm-reduction program, but it was his time at Hope Blooms that transformed his diet, encouraged him to start his own garden plot, and helped him appreciate the difference between “food you can grow and food you can buy in a grocery store.”

Other solutions to hunger can be as simple as starting a cooking club. Back at Bayers Westwood, Hemr and his friend Janice, a single mother thirty years his junior, have formed an extended family along with their neighbour Rudaina, a single mother from Lebanon. “They trade off on meals,” says Donna Sutton, “which has benefited them. They have more variety.”

Such initiatives shouldn’t be over romanticized. No doubt they bring people together and build community, but the food insecure, almost by definition, are often too busy trying to survive—working or looking for work, paying down tuition, taking care of their families, dealing with health issues—to garden, secure a land donation, or launch a salad-dressing business. A cooking club is a good idea, if you can find like-minded people. What if your neighbours are unsociable or don’t cook? Most solutions to food insecurity depend, to varying degrees, on the charity of others. If charity isn’t the solution, what is?

Katsumi* is the mother of three small children. By 2015, she and her husband, Joseph*, had moved their family to Toronto from Kyoto, Japan, after he was hired at the Canadian branch of a UK-based engineering firm. He loved his job but had an abusive boss. Katsumi worried for her husband’s mental health as she watched Joseph come home increasingly dejected. He couldn’t transfer to another branch because he and Katsumi had just bought a home— a three-bedroom, $320,000 townhouse. They decided Joseph would quit and look for work at a new company.

He assumed the job hunt would be easy. It wasn’t. There was no shortage of openings—in twelve months, he got ten interviews but no offer. Meanwhile, bills piled up: mortgage, cable, phone and internet, gas, car insurance. Life became a struggle. Their eldest daughter missed a school field trip because the family couldn’t afford it. And everything cut into their grocery money.

Katsumi eventually got a job at a downtown catering-and-event hall. She commuted each way by public transit to serve hors d’oeuvres to VIPs, while she could barely afford to put food on the table for her family. Soon, Katsumi and Joseph had nothing but pasta in the cupboard. Rather than get rid of their internet or phones, which were essential for finding—and keeping—work, they began using food banks. Katsumi tears up as she recalls the first time she set foot in one. “I was crying in the waiting room because I was thinking about my kids. I felt ashamed.”

Most food banks allow households one or two visits per month and give out two to three days’ worth of food per person. Katsumi found one bank that allowed a hamper every week; Joseph found another that gave out hampers every two weeks. It wasn’t enough. When I met with Katsumi on a chilly Sunday last November, her home wasn’t much warmer than outside. She and Joseph had lost their cable, their cell phones, and their internet and hadn’t turned on their heat or their lights. Katsumi was relying on a colleague to call her land line with her work schedule.

Valerie Tarasuk is a professor of nutritional science at the University of Toronto and leads Proof, the food-insecurity research program. She calls food insecurity “a very sensitive measure of material deprivation.” By the time someone is struggling to put food on the table, “they are struggling to meet all kinds of needs—not just those related to food,” she says. That’s why, Tarasuk argues, charity can’t be allowed to become the default answer to the food crisis. Moisson Montréal, the largest food bank in Canada, is now using digital technology to redirect food intended for the landfill to community organizations fighting hunger. Salt Spring Island Community Services converted a six-metre-long shipping container into a giant fridge in order to rescue soon-to-expire food items from grocery stores and farmers and deliver them directly to low-income families. Vancouver Coastal Health has developed an online map that helps people access low-cost or free meals as well as free or subsidized grocery items. While these initiatives might keep people alive, they are, Tarasuk claims, “a symbolic gesture.” Funnelling more and more corporate food waste toward impoverished people does nothing to address the root causes of the crisis.

Graham Riches, who has been studying the efficacy of food charities since the mid-1980s, agrees. “Our perception now,” argues Riches, former director of the School of Social Work at the University of British Columbia, “is that, because we have this edifice of food banks, the problem is being solved. But it hasn’t been solved. It has merely institutionalized this approach.” Eliminating food insecurity requires an appetite for difficult reforms: people need to be paid properly, they need access to good jobs, and they need affordable housing.

In November 2018, Zsofia Mendly-Zambo and Dennis Raphael, two health-policy researchers at York University, co-authored an article they called “Competing Discourses of Household Food Insecurity in Canada.” The researchers contend that the public has, for decades, been conditioned to believe that charitable efforts are the common-sense response to hunger across the country. The attempt to position hunger as a matter for charity can be traced back to the 1960s, when American antipoverty activists first debated how to frame the discussion around feeding the poor. Is it about a lack of income or lack of food? Activists chose the latter, reasoning that communities would feel a moral obligation to support charities for the hungry rather than to vote to raise taxes for social assistance. That’s what prompted the emergence of food banks, in which church-run donation programs paired with food manufacturers that had a surplus. It was only during the 1980s, when Canada’s welfare system struggled to cope with a very difficult recession, that our charitable organizations decided to adopt the US model.

Almost forty years later, more than 500 food banks are dotted across the country. According to Food Banks Canada, on average, 850,000 Canadians are fed through food banks each month—nearly 100,000 in British Columbia alone. The widespread legitimacy food banks enjoy, argue Mendly-Zambo and Raphael, has ended up “depoliticizing” food insecurity, making its solution more difficult. That’s because the least-debated fix—government policies that mend our failing social safety nets—is the most effective way of improving access to food.

“Food insecurity is about income,” says Paul M. Taylor, the executive director of Foodshare Toronto, a non-profit that operates more than forty-five travelling food markets—basically retrofitted buses stocked with fresh lettuce, okra, onions, berries, and broccoli. Targeting disadvantaged communities in the Greater Toronto Area, it delivered over 2 million pounds of low-cost, high-quality produce in 2017 alone. But Foodshare could distribute three times that and it still wouldn’t bring single-parent families and seniors any closer to affording the nutritious food they need. Since May 2010, according to the City of Toronto, the cost of a basic, healthy diet in the municipality jumped 18.4 percent; over the same period, the minimum wage rose only 13 percent. “Folks concerned about hunger,” says Taylor, who often sees customers scrounging for small change when paying for fruit and vegetables, “need to be talking about things like universal basic income and increases to the minimum wage.”

Those conversations seem increasingly hard to have in politics. Since being elected last June, Ontario premier Doug Ford halved a proposed increase to social assistance rates from 3 percent to 1.5 percent, delayed an increase to the minimum wage that would have brought it from $14 to $15 an hour, and deep-sixed the universal basic income pilot project, which was gathering data from three pilot sites in Ontario to understand whether a basic income could improve the standard of living for low-income people. With the pilot scrapped midway, there’s no reliable data for researchers. But we already know that relatively modest increases in income have been found to reduce food insecurity. In Newfoundland and Labrador, between 2007 to 2012, the rate of food insecurity among households living on social assistance was cut nearly in half from 60 percent after the government increased benefit levels, indexing them to inflation.

But if food-security advocates believe tax-based solutions, like better social assistance or a universal basic income, should be part of a coordinated strategy to help Canadians put healthy food on the table, the question of how we will afford them remains. Given the drain that hunger has on health care, mental health, and productivity, says Tarasuk, “We’re already paying for it.”

*Name has been changed to protect the source’s privacy.