Margaret Nazon grew up near Tsiigehtchic, a Gwich’in settlement in the Northwest Territories. For most of the year, she and her family would hunt, fish, and trap in seasonal camps, returning to their Tsiigehtchic log cabin for a week at a time, once around Christmas and once in the summer. In the community, she would watch her older sister and her friends’ mothers stitch beads into floral designs on velvet, stroud, and moose hide after their chores were finished for the day. At their invitation, she began learning how to decorate bracelets, headbands, and moccasins. But she didn’t particularly like beading.

“I was doing the same thing as everyone else,” she recalls. The women in the community taught her that flowers and geometric patterns were the only suitable choices of subject matter. They determined which colour combinations were acceptable: leaves had to be outlined with rows of dark-green beads and filled in with light-green ones; yellow and black were the only options for flower centres. She remembers experienced beaders requiring their students to tear out and redo any work that did not meet their standards of neatness and precision. Their rigour may have stemmed from the rules that apply when living and travelling in nature: “When you’re out on the land,” says Nazon, “you’ve got to follow tradition, otherwise you could get lost, you could starve, something could happen.”

Outside, Nazon developed a different passion. The local priest, Jean Colas, taught her and other children about the constellations above. In a part of the world where winters bring long nights, the skies can be particularly vivid.

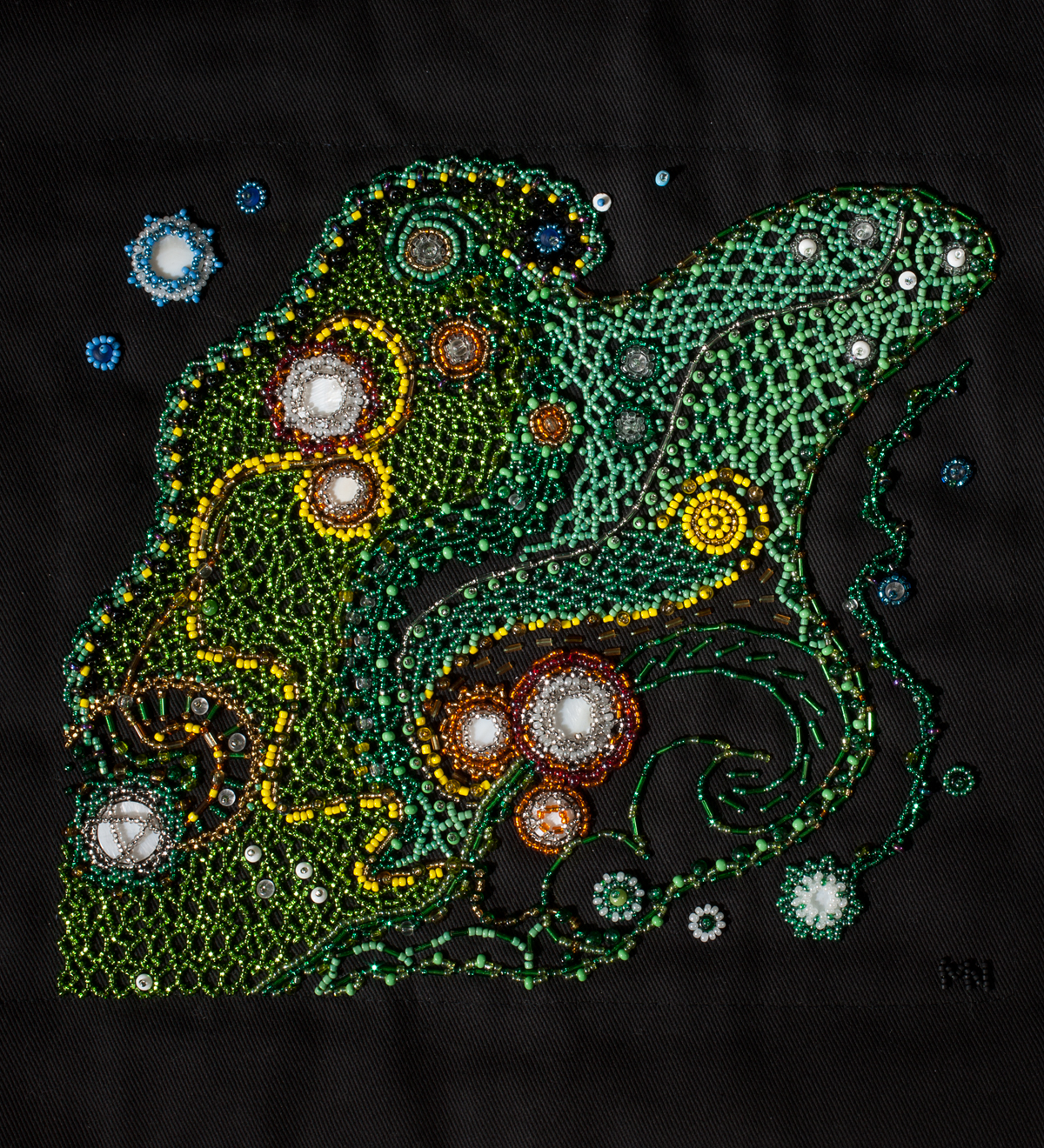

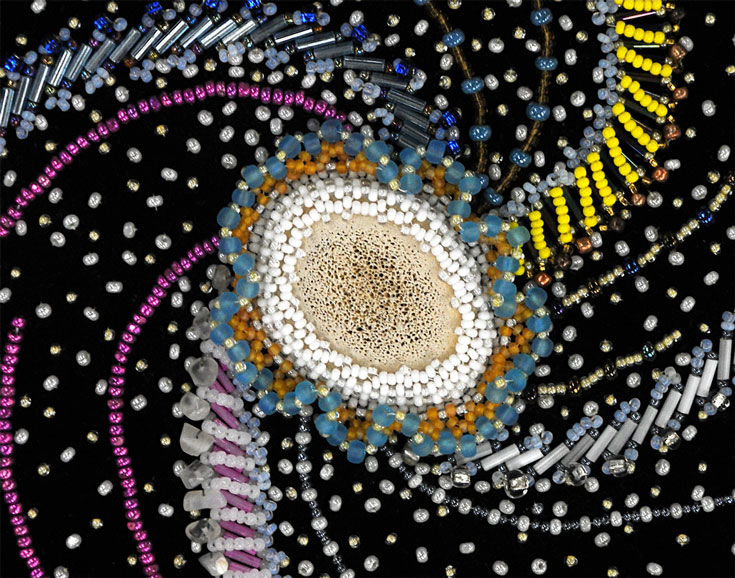

But it wasn’t until Nazon was in her sixties that her love for astronomy appeared in her beadwork. She remembers the day, over a decade ago, when her partner, Bob Mumford, showed her some Hubble Space Telescope images online. The swirling nebulae, star clusters, and galaxies reminded him of beadwork. Nazon agreed; she was particularly attracted to the whirl of colours and ocular shape of the Cat’s Eye Nebula. In the tradition that had characterized her beading experiences, she tried to create a precise replica of the image. This left her frustrated, and she eventually disassembled the piece.

When she read in more detail about phenomena photographed by the Hubble telescope, however, Nazon learned that many, including the Cat’s Eye Nebula, were composed of gases and other moving particles. This meant the colours and shapes captured would long have shifted by the time she saw them. That realization, she says, freed her to “go wild” with her designs. “If I make a wrong stitch, so what? I’m not a perfectionist. I don’t care if this colour doesn’t match with that one. It looks good to me.”

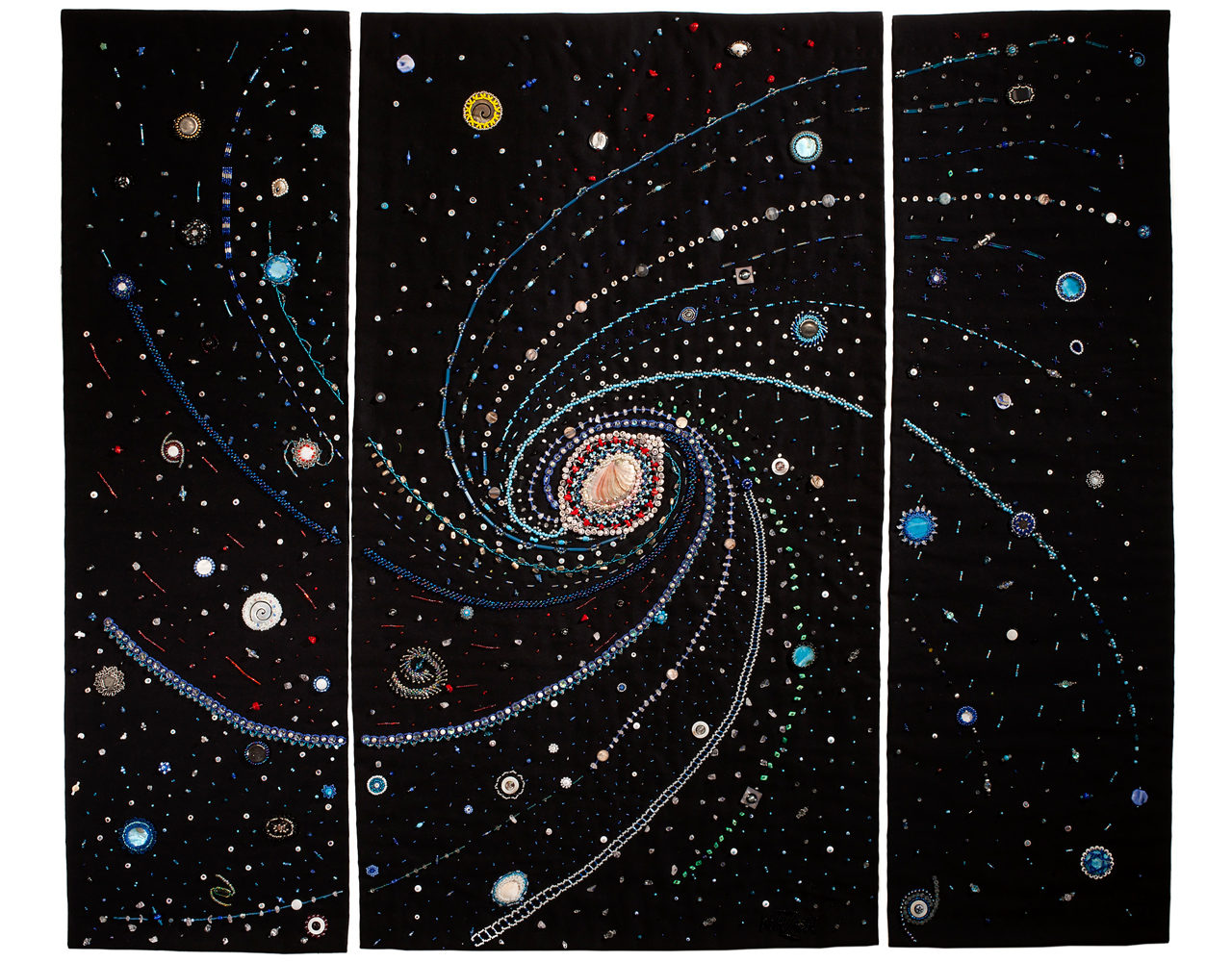

She began incorporating wooden and metal beads, spherical seed beads and tube-shaped bugle beads, fish vertebrae, bits of driftwood, and stones into her works. Thrift stores provided serendipitous finds such as shells and glass. A section of caribou antler became the centrepiece for Milky Way Spiral Galaxy.

When Rae Braden, the exhibit-design manager at Yellowknife’s Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre, visited Tsiigehtchic in 2015, she was struck by Nazon’s signature style—it’s still unusual to see beadwork that doesn’t fall within the standard floral and geometric themes. She helped organize Nazon’s first public exhibit, which opened two years later at the centre. Nazon’s art soon began gaining wider recognition: in the fall of 2018, independent curator Mary-Beth Laviolette included Nazon’s work in the Cosmos exhibit at Calgary’s Glenbow Museum.

“Up here, you’re going to get looked at if you’re doing something different with a traditional style,” says Inuk (Brendalynn Trennert), an Inuvialuit artist who creates three-dimensional designs using bundles of caribou hair stitched onto hide backing, a practice known as caribou-hair tufting. Despite Nazon’s break with the strictures of beadworking, northern artists have celebrated her ingenuity.

“I don’t know why we have to speak to this binary of traditional or contemporary,” says Tania Larsson, a Yellowknife-based artist who creates jewellery that draws on her Gwich’in culture. “The love of the land, the love of the universe, all these things embrace Indigenous values.”

As Nazon’s work gains popularity among northern artists, so does her commitment to mentoring others. In conjunction with her Yellowknife show, Nazon held a workshop to share her techniques with a group of NWT artisans. She encouraged her students to not simply replicate her approach but to develop their own styles. “Margaret would give them what they need to flourish,” says Inuk. “She is leaving an example. Next thing you know, they’re breaking their own trail.”