Welcome, newbie. Wan2tlk, one chatfly to another? I’ve got NB2D ?. What, you don’t speak TxtMsg? L2K, eh. N/P. It’s kewl. Promise you this: TTOYaL. :—)

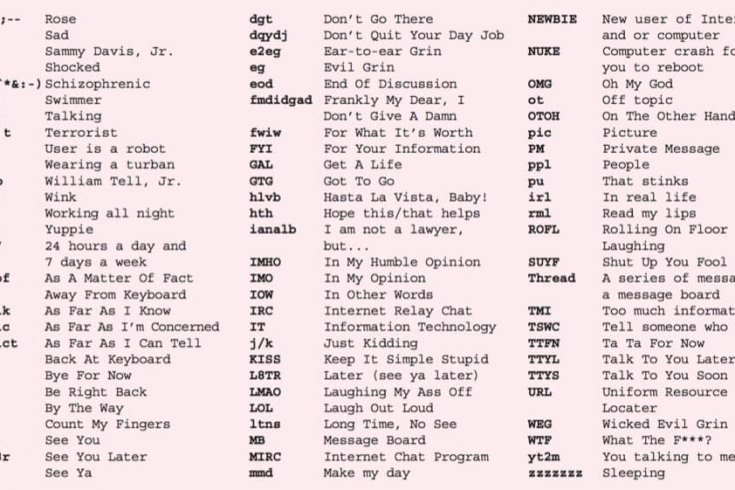

If you have to ask, you’re probably too old for text messaging (TxtMsg), the latest youth craze, complete with its own lexicon. All the characteristics of a hipster slang are in evidence: abbreviations and acronyms, symbols only known to the initiated, and an astonishing speed of exchange. Wan2tlk is “Want to talk?” and NB2D is “Nothing better to do.” L2K is “last to know,” and TTOYaL is “the time of your life. ?” Then there are the typed characters :—), called emoticons. An emoticon works if you tilt your head to the left, the colon becoming the eyes and the bracket the grinning mouth.

Two qualities of text messaging make it unique. First, where most street argots are particular to a society, this one is fast becoming universal. Its “street,” so to speak, is a vast one – the World Wide Web. Second, for all its resemblances to oral speech, text messaging isn’t spoken. It is written and, even then, hardly in the traditional sense. It exists solely on the computer or cell-phone screen, and is meant to be as ephemeral as an unrecorded, real-time conversation.

The Net has a short but lively history as a generator of languages. First developed in 1969, it only reached public consciousness in the early 1980s. (The term “cyberspace” dates from William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer.) HTML (hypertext markup language), the “lingua franca” of the Web, came together in the early 1990s. Home PCs and email established themselves in the same decade. Text messaging, bornin chatrooms such as MSN’s and nowmigrating onto mobile phones, belongs to the twenty-first century. But it already has its own dictionary, The Total TxtMs Dictionary, with more than 6,000 entries. There is a distinction between text messaging and the vocabulary of “netizens,” called “Net lingo,” which also has its own dictionary. The latter is older and more established, and has always had a literate bent. Much Net lingo is the product of techies, paid to spend their days in front of a screen. They may be cyber-geeks, but they’re also probably old-fashioned eggheads, raised on books, who enjoy showing off their wit and riffing on pop culture.

Neologisms are the specialty of Net lingo. A “drump” is a salacious middle-aged Internet surfer and a “spod” is an irritating amateur techie. “Netsploitation” involves taking advantage of the Net’s freedom to push a product. “Fram” is spam from friends and “to gonk” is to embellish the truth. That term is imported from the German gonken, which means to pull one’s leg. “You’re gonking me,” in cyber-speak.

Text messaging is something else.Chatrooms belong to ordinary netizens, often very young ones. Speed is imperative. Wit isn’t outlawed, but it isn’t especially prized. The majority of abbreviations in use are, in fact, short-forms for verbal cliches: 2T^ for “Two thumbs up” and KYSO for “Knock yourself out.” Mostly, they read as what they are: simple, declarative exchanges, the way people talk on the phone.

“Speakers” of text messaging must have an almost physical relationship with the computer keyboard. Net lingo is still about inferring complex meanings through words. With text messaging, the medium – the strokes available on a keyboard, the ability to talk to someone nearby or on a different continent – is at least part of the actual message. The relationship with technology, however glib, is less mediated, and more casual, than ever before.

Then there are the emoticons, “icons” that represent emotions. Their other name, “smileys,” suggests their purpose: to substitute for the “feelings” that might accompany a remark in a face-to-face exchange. At first glance, “classic” smileys, constructed from the keyboard, bring to mind primitive ideograms. Their meanings are strictly visual, and they display some of the wit absent in the messages themselves. Samples include :—0 for “wow” and X—( for “mad.” There are also smileys for characters and people: +:-) for “a priest” and =|:-)= for “Abraham Lincoln.”

More common, however, at least in chatrooms such as MSN’s, are the smiley faces. With a click of the mouse one selects the appropriate “emotion.” The smileys are intended to behave as would a wink or a shrug, more body language than verbal cue. While these symbols may not do much to make text messaging respectable, kids love them, and coat the simplest remarks with grins or contortions, as they might once have covered a letter with stickers.

For some of us beyond a certain age, though, such an argot triggers associations. The twentieth century told cautionary tales about secret dialects. The authors of 1984 and A Clockwork Orange warned that language, if degraded and made cabalistic, turned sinister. Martin Amis’s 2003 novel, Yellow Dog, has a character semi-stalking a journalist with text messages. She types sentences such as this one: “come 2 me on your return. only when u & i r 1 will i feel truly @ peace. 10derly, k8”

Amis wants the notes to be creepy, if only for their infantilism and disrespect of proper English. But he may be reading too much into the slang. His character’s emails are overly long and burdened with an anxiety about language that doesn’t exist among text messagers. She isn’t using the keyboard in the proper spirit.

That spirit, the spirit of text messaging, is almost certainly closer to Marshall McLuhan than George Orwell. The communications sage foresaw the emergence of a generation rendered both physiologically “electronic” and spiritually connected by computers. Chat rooms aren’t his “global village.” They are, however, evolving a global dialect he would recognize: inclusive and unironic, versed in symbols as much as the alphabet. I have a Chinese friend who finds it easier to communicate in text messaging than in written English, and Mandarin chatrooms in China already employ a number of the more popular symbols.

Is text messaging in English? Clearly. But it is also being written, or spoken, online, using other sorts of linguistic signs. It communicates in a crude but ingenious manner, one that can bridge divides. The biggest barrier, curiously, may prove to be age. After a point, adults want to speak meaningfully. For that, you need words: the right ones, and more than a few.