In February, 2002, when Daniel Libeskind presented his design for Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum expansion, a thousand people came to hear him. A smartly dressed group with the muted, dark-hued cool of the design world filled the chairs and stood in the aisles in the museum’s Currelly Gallery. An overflow crowd watched him on a large screen in an adjacent room. It was a much larger audience than the other two finalists—Canadian Bing Thom and Italian architect Andrea Bruno—attracted. The fifty-six-year-old Libeskind waited for his introduction, standing to the side and smiling, a beaming, nervous adolescent’s smile. Short, trim, wearing a well-tailored black suit and cowboy boots, Libeskind took the stage like a veteran politician, with a barrage of ideas and a rushed musical cadence. He was connected to Toronto, he said. He had taught there, his wife was a Torontonian. The idea for his dramatic crystal design had been inspired by a visit to the ROM’s mineral gallery, among the amethyst and quartz. He talked about the “wow factor,” a term that came out of the advertising business but has settled comfortably in architecture.

When Libeskind was announced as the winner a few weeks later, there was little surprise; word was that ROM director William Thorsell had favoured Libeskind. “He wanted the wow factor to put the ROM on the map. It was pre-ordained,” says Michael Miller, an architect and professor who was a member of the working group that chose the long-list of twelve candidates.

Libeskind wasn’t a celebrity at the time. Only three of his designs had been built, but one of them, the Jewish Museum in Berlin, had won international acclaim for its jagged, geometrical shape. He had also won the competition for the expansion of London’s stately Victoria and Albert Museum. His star was on the rise and his work was iconic and singular.

Thorsell also wanted a design that would attract money: when the selection process for the ROM design began, none of the estimated cost of $200 million had been raised. Part of the written criteria of the commission was the architect’s willingness to participate in fundraising. When the field was winnowed to three finalists, the selection committee discussed the promotional verve and fund-raising qualities of each candidate. It was noted that the Italian architect, Bruno, has difficulties with English, a handicap for fundraising. Thom is a pleasant, low-key, West Coast architect. But Libeskind has kinetic language skills, a speed rap that routinely incorporates references as diverse as Greek etymology and the Marx brothers. His design was the most dramatic, and he had the political skills to work the room, to bring magic to that grey town.

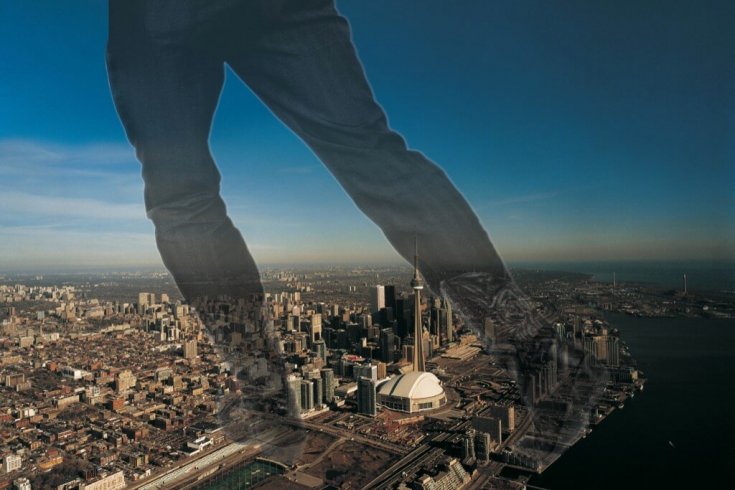

“We’ve been living in Toronto for too long,” William Thorsell said. By this he meant the pale Protestant town of the nineteenth century that had survived into the 1960s, a conservative place that once looked enviously south toward Buffalo. The late historian Eric Arthur, who, in 1964, glimpsed a romance in the cityscape that eluded all but the most ardent lover, chronicled Toronto’s expansion, a Roman grid moving westward over ancient trails that ran to the lake. But Arthur’s love was largely unrequited. “Surely no city in the world with a background of three hundred years does so little to make that background known,” he wrote plaintively. Barring a few outbreaks of activism, the public has displayed a heroic indifference. Churches and university buildings survived, as is their habit. But thirty years of waterfront development schemes have died offstage, leaving an ad hoc string of condominiums that may, in a decade, achieve the louche crumminess of the Costa del Sol. Toronto is defined by the vast sustaining error of the Gardiner Expressway, which divides the downtown from the waterfront, and by symbols such as the CN Tower, itself a mistake of sorts; it was designed as the centrepiece for a project that was never built. Unfulfilled ambition is the most palpable urban trope, but there is always the familiar damning prayer: It is livable.

Libeskind’s crystalline shapes exploding between the two original wings of the ROM represent the most dramatic architectural forms seen in Toronto since Viljo Revell’s City Hall, which was completed in 1965, and his design has invited the same exuberance and wariness. (Frank Lloyd Wright, who died before City Hall was built, criticized that design as “a headmarker for a grave.…Future generations will look at it and say: ‘This marks the spot where Toronto fell.’ ”)

The ROM project coincided with a flurry of ambitious design in the city. Frank Gehry was hired to redesign the Art Gallery of Ontario, located just blocks from where he grew up. British architect Norman Foster was doing the Leslie L. Dan Pharmacy Building on a prominent University of Toronto site. William Alsop, the Sid Vicious of modern architecture, designed a building for the Ontario College of Art and Design, an opaque box hovering 26 metres above ground on brightly coloured stilts. And an opera house designed by local architect Jack Diamond was finally underway, a project that has a history too long and bloody for even Wagner to stage. This renaissance grabbed the attention of a city that was still, for the most part, imagined by colonial bureaucrats trying to recreate the Georgian comfort of home. The city became, in its modest way, a crucible for modern architecture. At the very least, these new forms revive an ancient argument: what is a building’s responsibility? Should it look to the past and to its immediate context, or can it exist as a singular monument? Libeskind’s ROM design, which has drawn both worshipful praise and outright hostility, emerged as the focus of this argument.

What William Thorsell was seeking with the ROM redesign was the still-audible echoes of the Bilbao effect: the ability of architecture to transform an institution, an economy, a city. Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, famously transformed a minor industrial city into a tourist destination. Bilbao itself started out as the Sydney effect; Gehry was initially told by the Basque government that it wanted another Sydney Opera House. From that point there has been a downward spiral that has captured the imagination of cities worldwide. The extent to which it has infected civic sensibilities was seen when the director of Rome’s National Center for the Contemporary Arts told the architect Rem Koolhaas that the city needed “a building that does for Rome what the Guggenheim did for Bilbao.” This is one legacy of the Bilbao effect: to reduce the grandest of cities to River City, Iowa, hoping that the next travelling salesman will deliver salvation. Bilbao came with an oft-quoted array of statistics (generating $500 million in economic activity in its first three years and $100 million in new taxes). When Vincor CEO Donald Triggs persuaded Gehry to design a winery in the Niagara peninsula, it was a marketing decision as much as an aesthetic one. The building would draw attention to the wine, and bring people to the winery. The cost, Triggs said, was his marketing budget for eternity.

But subsequent attempts to reproduce the magic of Bilbao haven’t always succeeded. Gehry’s Experience Music Project building in Seattle opened to great fanfare; eighteen months later, admissions were down by more than a third and 124 employees were laid off. Seattle represents the dark side of the Bilbao effect: the sense that smaller, more provincial cities are getting substandard knockoffs from great architects. Gehry’s defiantly unlovely EMP building is referred to locally as “the hemorrhoids.” Robert Venturi’s Seattle Art Museum has been criticized as being both dull and confusing, and Rem Koolhaas’s new public library is described as a “horror.” “It’s very provincial to want the newest and the bestest,” a Toronto architect said, and Seattle is paying for that provincialism, becoming a kind of anti-Bilbao.

In May, Gehry himself was quoted in the New York Times as saying the Bilbao effect was “dead in the water.” The era was over. Five months later, though, the concept was revived by Gehry’s own Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, which was touted as the remedy for L.A.’s historically formless downtown. Toronto was anxious for Bilbao, a little bit needy and a little bit late, both qualities of a mark. But the appetite for greatness, for recognition, was there.

The ROM design is emblematic of an architectural era that is both exciting and undefined. “Architecture is in an era of groping,” said the architect Michael Miller. “We’re groping with postmodernism and deconstructivism. There is no strong design determinant. The computer is the design determinant.” The lack of clarity in the profession is reflected in universities. “At McGill University,” wrote critic and professor Witold Rybczynski, “as at all schools in the North American continent, there is no longer an accepted canon of architectural principles.” Instead, Rybczinski argues, there is rampant individualism, the logical heir to the Me Decade.

Cities want the drawing power of an iconic building, and the Bilbao effect has nurtured a climate that both sustains and rewards dramatic architecture. Rybczynski offers the example of Robert Venturi, who was commissioned to design a new concert hall in Philadelphia, his hometown. His graceful, integrative design lacked the punch that the city wanted; he was fired and the budget was raised from $60 million to around $250 million and the commission given to Rafael Vinoly (who, with the THINK team, was a finalist in New York’s Ground Zero competition). “Vinoly’s glass vault,” Rybczynski writes, “however impressive its drama, is an alien presence. The devaluing of context is even more flagrant in international competitions, in which architects are expected to add major civic monuments to cities they may have visited only once or twice.”

This is the central criticism of Libeskind, that his buildings are alien forms that ignore their context. In this sense, Libeskind is recreating a failure of Modernism: the inability to communicate anything meaningful to the local public. The International Style was underpinned by a noble philosophy of global egalitarianism: one world, one building. Shelter became a universal, Utopian idea. So a Mies van der Rohe tower in Chicago (the IBM buildings) would look like a Mies in Toronto (the Toronto-Dominion towers). The buildings were based on functionalism, an aesthetic that was devoid of ornament or any historic reference.

Post Modernism responded by linking architecture to something local, to a city’s history, or existing buildings. So you got prairie banks that echoed the form of grain elevators. There was a double-coded approach: the general public would instinctively recognize the structure and its references, while other layers of meaning existed for the initiated, i.e. the profession. The local vernacular, the genius loci, was important, but Post Modernism allowed for goofy excess and trite metaphors. What has followed is a series of “isms,” architectural spur lines that lead off in various directions but don’t go very far, or connect to anything else. There is now a collection of unrelated signature styles, bound only by a loose philosophy.

Libeskind has been lumped in with the deconstructivists, a category that includes Frank Gehry. Gehry’s famous deconstructivist Santa Monica house has been interpreted as representing the fragmented Californian culture that surrounds it. (Gehry himself says this isn’t necessarily the case.) Libeskind’s bold crystals stand alone, though he attempts to integrate them with a local narrative. He described the crystalline extension to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London as a dialogue between the old and the new, an aesthetic conversation. The jutting crystals of the Denver Art Museum reunite the city’s historical and cultural life. The crystals of the ROM in Toronto have a more mundane, though local provenance: the museum’s mineral gallery. The designs approach the sameness of Mies van der Rohe’s towers, but the narratives vary, each providing a hook for the local audience.

Libeskind’s narratives may be the natural result of twenty years spent in academia, immersed in architectural theory. “In architecture schools, you have to justify your building,” says David Janson of Adamson Associates Architects, in Toronto. “The defence is verbal; you have to justify it with a story. You learn to post-rationalize. It’s easier to draw first and come up with a story later.”

Words are integral to Libeskind’s work. His designs have rarely engendered immediate public sympathy (a survey conducted by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation showed Libeskind’s design for Ground Zero as the choice of 25 percent, with THINK’s design capturing 33 percent, and 42 percent liking neither), but he is tireless in breaking down resistance, and, eventually, he succeeds. He gave hundreds of lectures in Germany to build support for his Jewish Museum. In London, where he encountered fierce resistance to his design for the V&A, he attended dozens of meetings: the Georgian Society, Victorian Society, resident groups, heritage committees. At every meeting he waited until the last angry citizen, critic, and outraged dowager had expressed his or her view. “Daniel never sees it as an insult or an affront,” his wife Nina says. “He truly believes in a public process.” That his buildings get built is often the result of politics and sheer will.

His relationship to language is often intentionally baroque. (Of his Jewish Museum, Libeskind wrote, “The Jewish Museum is conceived as an emblem in which the Invisible and Visible are the structural features which have been gathered in this space of Berlin and laid bare in an architecture where the unnamed remains the name that keeps still.”) In the Architectural Review, Boaz Ben Manasseh wrote, “It is astonishing that Daniel Libeskind can write so much nonsense without endangering his reputation.” And in their essay, “Death, Life and Libeskind,” Brian Hanson and Nikos Salingaros observed that “One should be wary of drawing conclusions from Libeskind’s own words, because he is a master at producing a veritable fog of words on demand.”

Libeskind presents the engaging dichotomy of a deadly serious intellectual on the one hand, and a determined salesman on the other, a cross between Jacques Derrida and Professor Harold Hill in The Music Man. When he appeared at a town-hall meeting at Toronto’s St. Lawrence Centre last May, his speech had symphonic patterns, moving from the esoteric to the familiar. At times his words were as precise as his angled geometries; at other times, they appeared in an almost arbitrary jumble. He talked in breathless metaphors that linked T. S. Eliot and the Grand Canyon, and spoke about the “patterns of relationship that inscribe the city as a book of the future.”

“Buildings have always told stories,” Libeskind said. And if they don’t tell a story, one can be manufactured. Architect Jon Jerde, who has designed malls as well as Las Vegas hotels such as the Bellagio, has argued that the architect’s job is to design narrative experiences. Jerde is dealing with the masses, and his stories are blatantly commercial, bestsellers. Libeskind’s stories may be little more than marketing strategies for his esoteric shapes, but they serve another purpose. His buildings adamantly embrace the future, and stories are a familiar comfort when facing that cold, unknowable maw.

In architecture, at least, the future has arrived. There are paperless offices now, where all design is done in three dimensions on the computer. There are software programs that reduce months of engineering calculations to mere days. New materials and new heating and cooling technologies all allow for experimental forms: sculptural, geometric, soaring, organic. “We can build anything we want to now,” says Michael Miller. “The question is: Should we?”

Libeskind is among the generation of architects who disdain contextualism, whose buildings look to the future rather than the past. Museums have been the vanguard for this new architecture, though the futuristic shapes are filtering down to libraries, office buildings, churches, houses. The external transformation of museums from efficient boxes to exhibits themselves has been prefaced by internal transformations. In the past two decades even state-run European museums have been slouching toward a business model. Directors will tell you that they are competing with baseball, hockey, cable TV, with malls and Britney Spears for the consumer’s attention and money. The need to reconcile scholarship and entertainment, to find a balance between science and showmanship, has been an ongoing experiment in museum circles. Curators have been told that they need to tell stories rather than simply put the wares out for display. William Thorsell’s predecessor, Lindsay Sharp, was accused of trying to “Disnify” the ROM, and of doing a poor job of it. Sharp talked of “edutainment” and “infotainment.” And now into that club comes “architainment.”

Iconic architecture has produced some extraordinary buildings, but as an ad hoc school, what kinds of cities will it produce? Will they begin to resemble World Fairs, an assembly of startling, unrelated structures designed to bring customers into the tent? “Buildings are citizens,” one Toronto architect said. “They have a responsibility.” All architectural movements evolve or die, and most of the deaths aren’t pretty. Modernism left banal mirrored towers scattered through the world’s downtowns, the po-mo graveyard is littered with childish metaphors, and deconstructivism has saddled us with Toronto’s CBC building, Philip Johnson’s sullen cartoon.

World fairs open with such optimism, exuberantly embracing a mediated, hopeful future, but they often end sadly. Montreal’s Expo ’67 was a glittering success but it left Buckminster Fuller’s burned-out dome, and the French pavilion converted to a casino. Appropriately, the site was used for Robert Altman’s dystopic 1979 film Quintet, which was set in a barren, survivalist future. Our own future could present a stark, Darwinian landscape where everything is run on a business/entertainment level: sports, schools, churches, museums, marriage.

Libeskind sees a happier future, one where his crystalline shapes are welcome and enduring. “A good building has enough depth to recreate itself,” he says. “Look at antiquity, look at how many times those buildings have been reinterpreted. These are directions: as white, as colourful, as scary, as inspiring, as timid, as pure, as brutal, because they have a lot of substance. Any work of art, or any city—Rome, New York, or even Toronto—it keeps evolving.”

Still, if the future of architecture is unclear, Libeskind provides a glimpse of what the successful twenty-first-century architect may look like: fluidly international, a multilingual salesman who brings celebrity, drama, and a kind of political shamanism to the built form.

Architecture, Goethe once noted, is frozen music. In the case of Libeskind’s buildings, it might be the music of Arnold Schoenberg, whose unfinished opera Moses und Aaron was an inspiration for the Jewish Museum. Before going into architecture, Libeskind considered a career in music. “I had the fatal history of starting on the accordion,” he says, perched on a sofa in the lobby of Toronto’s Four Seasons Hotel. “The accordion is one of those strange instruments that crosses boundaries, folk, ethnic, a small baroque instrument that is portable. In a way, it’s not a bad analogue for my life.”

Libeskind grew up in post-war Lodz, Poland, and moved to Israel as a teenager to study music, through the America-Israel Cultural Foundation Scholarship. “Itzhak Perlman said to me, ‘You should have played the piano. Why the hell did you ever play this instrument?’ Because that was my fate.” Libeskind went on to study piano, and moved to New York in 1960, where he eventually switched to architecture. He studied at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, and did postgraduate work at Essex University, then taught at several universities, an itinerant, sought-after intellectual. He remained an academic until 1989, when he won the competition to design the Jewish Museum in Berlin. The cultural politics of that job were labyrinthine and protracted, and Libeskind moved to Berlin to address them. “I moved out of naïveté,” he says. “But I think it was because of this naïveté that the building got built. This project was scrapped by the board of the senate, there was no money for it, no one wanted to do it. It took ten years.”

That it got done was due in part to the political efforts of his wife, Nina Libeskind. In the preface to Daniel Libeskind: Jewish Museum Berlin, Libeskind thanks his partner, who “steered the project across the unsettled waters of politics and public opinion.” Nina Libeskind is the daughter of the late David Lewis, who was head of the New Democratic Party, and the sister of Stephen Lewis, now a UN Special Envoy, and she grew up with a refined sense of politics (as well as a fanatical devotion to sports). “We won the competition in 1989,” she says, “and in ’89, of course, the wall fell, and with that came the realization that a huge amount of money would have to go into infrastructure, especially in the east. And there were a large number of people who wanted to take the money out of the museum and put it into an Olympic bid.” Her husband campaigned tirelessly, taking his case to the people. “He went to four or five hundred German cities, towns, talking to groups, any group.”

The political and funding battles for the Jewish Museum went on for a decade, a delicate subject that opened wounds. A legislator who supported Libeskind was killed by a letter bomb. When the Jewish Museum opened in 1999, it was widely acclaimed, and attracted 250,000 visitors before it contained any exhibits. The building itself was a star. It had accomplished, presumably, what the proprietors wanted: instant recognition. But exhibitors had trouble working in its jagged spaces, and there was criticism from architectural traditionalists that the building competed with, rather than accommodated, the exhibits: they were both art.

“[The notion of] the architect as artist is a dead end,” one local architect said. “It doesn’t develop a set of principles or a school of architecture that can be taught or leads anywhere. The artist has licence, but the architect has to consider the end user and the political, social, and economic context.”

Libeskind is both artist and politician, and his work comes with two decades of theory, a collection of writings that read like manifestos. “By dropping the designations ‘form,’ ‘function,’ and ‘program,’ ” he wrote, “and engaging in the public and political realm, which is synonymous with architecture, the dynamics of building take on a new dimension.”

Where does the recurring crystal shape come from? “I have no idea,” Libeskind says, laughing. “Intuition, you draw something. Forever you draw something and you’re stuck. Architects don’t have hundreds of ideas, or writers, or Mozart even. They pursue one idea. Where it comes from, who knows? But I like the precision of the geometry, I don’t like the blobby indeterminate approach. I like architecture that is very crisp and very definite and kind of uncompromising in its relationship to the sky, to the horizon, the profiles that it presents, the massing of it.”

The twentieth floor of the Millenium Hilton hotel in Manhattan looks down on the collective wound of Ground Zero, an immense crater filled with workmen, machines, and debris. The offices of Studio Daniel Libeskind are a block away, on Rector Street. Just as the Libeskinds moved to Berlin for a decade to address the politics of the Jewish Museum, they have now moved to New York to deal with the equally charged politics of Ground Zero. There are twenty or so architects in the office, most of them young, working at cluttered common tables, gazing at computers. It is a purposefully unstructured office environment, one that attempts, Libeskind says, “to break through into the excitement, adventure, and mystery of architecture.”

Other members of Studio Daniel Libeskind are in Switzerland, where Libeskind is doing a shopping centre. There are roughly 120 employees worldwide. A team remains in Toronto, sequestered at the Bregman + Hamann offices, the associate architects of the ROM project. There they work odd hours, some arriving late and working until four a.m. It is a young, international group, devoted to Daniel, expounding on his genius and methods. There is a mood of Warholian revolution.

Nina Libeskind manages all the offices. She has an array of communication devices—a Blackberry, a cellphone, a Treo, and her computer, and she frequently picks one up to deal with personal matters, political issues, press releases. The most recent model for Ground Zero sits on a table. Libeskind’s Freedom Tower is flanked by four office buildings that are placed in a partial spiral that mimics the swirl of the Statue of Liberty’s robe. “They want to move the Freedom Tower,” Nina says, “but we’re sticking to our guns on that one. And they want five office buildings instead of four. We’re sticking on that one too. There’s progress.”

Progress has been slow and hard-won. The selection process to choose a design for Ground Zero became—perhaps inevitably, given the political and financial egos involved and the national import of the commission—a bonfire of the vanities. The competition process lacked clarity. Like the ROM competition, it was perceived as a fishing expedition rather than as a standard architectural competition. Much of the public was unclear as to whether it was commissioning an idea, a design, or an architect. More problematic was the attenuated profile of the client. Who was the architect working for? Was it the Port Authority, which owned the land, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, a political body created to administer rebuilding, or Larry Silverstein, the developer who controlled the World Tr ade Center leases? Or was it the citizens of New York? Or the American people? There were other stakeholders. The city of New York has an interest in the streets and parks on the site. “Then you have Westfield,” Nina said, “which is the retail component, who are concerned about how the design works for retail. You have the families of the victims, the local residents. There are lots of taskmasters. The responsibility is quite clear; what is interwoven is the authority.”

There is also the politically charged issue of what the site symbolizes. The British philosopher John Gray suggested that the collapse of the towers was symbolic of the collapse of the myth of Western civilization. In America, the symbol has been much broader and more marketable: the site represents heroism, and the resilience of a people. These various minefields taxed Nina Libeskind’s considerable political skills. “The dignity of growing up in a family of New Democrats has stood me well in Europe and Canada, and in cities like San Francisco and Denver,” Nina said. “New York is a tougher field. Everything here is in a fishbowl, and the stakes are just so incredibly high. We’re under a lot of public scrutiny. The [New York] Post, which is not sympathetic to us, had Daniel on the gossip page, sighted at the Strand bookstore, reading a book about medieval architecture. I said, ‘Well, thank God you weren’t in the erotica section.’ It’s like politics.”

Libeskind campaigned vividly and, at times, acrimoniously for the job. Studio Daniel Libeskind hired a publicist in New York, and played on his New Yorker status. (He is an American citizen, though, at the time, he was still living in Berlin.) He appeared on Oprah and was accused, in the world capital of self-promotion, and with the indignation that TV evangelists muster so easily, of being a self-promoter.

With Ground Zero, Libeskind took the idea of narrative to Dickensian lengths. The crystalline spire of the Freedom Tower was to be 1,776 feet tall, embodying America’s independence, and its shape was to echo the profile of the Statue of Liberty. It was a narrative that was partly told in the first person. “I arrived by ship to New York as a teenager,” Libeskind wrote, “an immigrant, and like millions of others before me, my first sight was of the Statue of Liberty and the amazing skyline of Manhattan. I have never forgotten this sight or what it stands for. This is what this project is all about.” The design was hard-edged, glittering, and rigorous, but the story was Capraesque. And, as any Hollywood producer will tell you, schmaltz works. The heroes of 9/11 would be celebrated by the “Wedge of Light.” On every September 11, between 8:46 a.m., when the first plane hit, and 10:28 a.m., when the second tower collapsed, “the sun will shine without shadow, in perpetual tribute to altruism and courage.” This was challenged by Eli Attia, the architect of the Millenium Hotel, who said the site would in fact be in shadow for much of the time. Libeskind’s response in the Times was rambling, and suggested that the gesture was metaphorical rather than literal.

In a public debate with Libeskind over whether to build anything at all at Ground Zero, the author Sherwin Nuland said that he would be offended by any piece of architecture that went up, because “ultimately, architecture is about the architect. What would you have people think about at Ground Zero? The name Libeskind?”

Libeskind responded, “You have a fascist idea of architecture that comes straight from Ayn Rand.”

The The New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp originally championed Libeskind’s proposal, describing it as a “perfect balance between aggression and desire,” but, when the field was winnowed to two, he reversed his position, writing that it was “astonishingly tasteless, emotionally manipulative and close to nostalgia and kitsch.” An employee of Libeskind’s initiated an e-mail campaign to have Muschamp fired. Nina confronted him on his turnabout. “I asked him very bluntly,” she says. “Muschamp said he thought the language could be appropriated by the right.” Libeskind’s narrative reduced to a Republican slogan.

Larry Silverstein emerged as the biggest threat to Libeskind’s plan, which he described as “ten acres of unusable office space.” Silverstein, various politicians noted enviously, was the only one with the money to rebuild, and money is the club that gives democracy its zip. The negotiations between Libeskind and Silverstein were reported like the Tour de France in the papers; each day someone new woke up wearing the yellow jersey. What was called, in Silverstein’s camp, “the most significant real estate transaction in the country,” and, in Libeskind’s camp, the most important architectural commission in the country, ended with Libeskind retaining much of his master plan. But he was now associate architect, with David Childs of Skidmore Ownings & Merrill as the design architect. Both sides claimed victory. “It’s a tremendous victory for us,” Libeskind said. “The papers said Libeskind compromised. They should have said Silverstein compromised.”

In the following weeks, Libeskind’s plan was further eroded and Silverstein brought in more architects—Norman Foster, Jean Nouvel, and Fumihiko Maki—to design three of the five office towers. By November, little was left of the original vision. Another symbol emerged at the site, more pragmatic and deeply American than democracy or heroism: money talks. A week later, Libeskind was philosophical. “The process is working with the market,” he said. “With partners, with retail, with the Port Authority, the developer, the money. There are certain indestructible rules to the market. You have to somehow create something greater than what you started with. If you’re lucky.”

If Ground Zero no longer represents Libeskind’s initial vision, it did cement his celebrity. Over the past year, he has appeared in an Audi advertisement, been interviewed in the New York Times style section on his glasses and his cowboy boots, and become a daily fixture in the American media, recognized on the street. He now occupies a place that only Frank Gehry could claim (and Gehry has warned of the pitfalls of celebrity). He is what an advertiser would call a global brand. Thorsell’s choice now looks like genius.

Celebrity is important, in part because of the way public institutions are funded. For the past fifteen years, the ROM has had declining operating budgets. Governments are both less interested and less able to fund public institutions. And private money in Canada has remained, in comparison with American philanthropy, relatively private. Toronto is still defined by old money, its shape resembling the old ROM: vast, stately, and hoarded. But new money has been attracted to Libeskind’s design in spectacular fashion. Michael Lee-Chin, the Jamaican-born owner of the country’s largest privately owned mutual-fund company, gave the ROM $30 million.

“Fundraising is a reality,” Libeskind said. “That’s my role as an architect. How do you make a building a reality? Architects are part of the marketplace. The idea of the master architect has changed.” In the spring, Libeskind gave a lecture to University of Toronto students, complaining lightly of this change. “He said he was jealous of us,” said Vered Gindi, an architecture student. “We got to design all day. He had to be a politician, convincing mayors, raising money, flying around.”

Libeskind enjoys both the advantages and dire weight of celebrity. He is courted the way film stars are and for the same reason: he can open, as they say. The presence of Bruce Willis in a movie guarantees at least a respectable opening weekend. After that, success depends on word of mouth. Libeskind can open a museum, but the success of his designs will be measured, in part, by the repeat business. Celebrity buildings, like celebrities, don’t have to do much to awe. It is enough that they are there. People seek them out, they gawk, and tell the folks back home that they thought they’d be taller. By definition, they are not part of the hoi polloi, they don’t fit in. If they did, they would lose their cachet. But celebrities pass out of sight, willingly or not, where buildings remain for decades, sometimes centuries.

The ROM is guaranteed initial success. William Thorsell, whom Libeskind praised as a brilliant client and collaborator, incorporated sound prescriptives as part of the competition’s mandate. The winning design had to address Bloor Street, the elegant parallel halls were to be restored to their original grandeur, the walls taken out, the dropped ceilings removed, the windows unshuttered. Druxy’s Deli, which occupied one of the ground-floor wings, has been supplanted by a First Nations gallery. Certainly the new building will lend drama and a focus to an intersection that is one of the city’s most gracious. Some of the building’s strengths, as with City Hall, will be in the rejuvenating effect it has on the immediate area. The creation of Nathan Phillips Square gave the city its first piazza, a place where it could meet to celebrate and protest, to see itself. The section of Bloor that faces the ROM has already begun a rehabilitation, but it will be years before the ROM can be assessed as innovation, or fad, or something else entirely.

There is a bell curve to popular culture, noted the architect Michael Miller, one that follows the arc of graffiti, which went from social protest, to individual statement, to fad, to wallpaper. In ten years, Torontonians may be celebrating the ROM as one of the city’s central jewels (and even traditionalists acknowledge the need for the occasional jewel). Or they may be engaged in a pissing contest with Denver over whose crystals are more world-class.