Pink, golden yellow, and light blue bloomed on my computer screen as I steadily drew one tiny digital flower after another while sitting inside my neighbourhood Starbucks. By April 2016, this had become a somewhat daily routine. Unemployed—or, rather, underemployed—and living with my parents, I’d pack up my art supplies, take the half-hour walk downhill to Streetsville, an area in Mississauga, Ontario, and draw all day. I knew I was creating something beautiful and meaningful. Although I didn’t exactly believe it was something life changing. At first, I just thought of the drawing as a simple piece, something to remind myself that life doesn’t always happen the way we plan it. I expected it, like most of my other artwork, to gain a handful of comments and likes and then fizzle away on social media.

It didn’t.

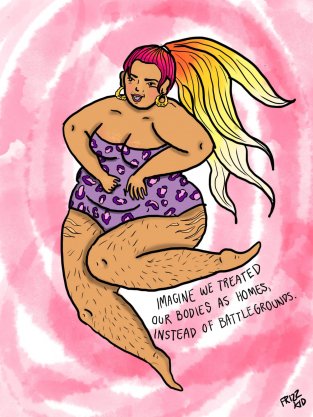

I had drawn an EKG line of little flowers with the words “healing is not linear”—a popular phrase among therapists and counsellors—sprawled over top. Within a few days, it went viral. Dozens, then hundreds, then thousands of notifications poured in from Tumblr and Instagram. Reading all the messages telling me how people connected with my piece made me want to make more. Soon, I had decided to start a new artistic series. I created more affirmation drawings filled with messages of self-care, mental wellness, feminism, and compassion. One piece reminded people that all bodies are good bodies. Another noted that productivity doesn’t determine someone’s value. These straightforward statements contradict so much of what people hear about their worth, about what they should look like, and about how they should live their lives.

Since then, I’ve drawn nearly 200 affirmation illustrations, and I’ve seen a steady increase of social-media love. I’ve gone from a small handful of friends following me to over 40,000 followers on Instagram. People have tattooed my work on their bodies. Today, I frequently receive messages about the positive effects my work has had. With each message that asserts I’ve helped someone heal, even just a little bit, my heart swells. But my brain also buzzes with the question: Why now? The term self-care has catapulted its way into our daily lexicon. I’ve used it to describe my work, and I’ve seen it used to sell expensive beauty routines. So, even as I benefit from its growing popularity, I have to wonder: How much of self-care actually has to do with care?

It often feels like we are living in an incredibly volatile time. I have read more than one article that calls millennials the most stressed-out generation in decades. I’m not surprised. I often feel like we have inherited an absolute mess. There’s the climate crisis, precarious employment, student debt, and the seeming ubiquity of racist and misogynistic comments and posts online. #MeToo exposed the vast amount of harm many of us are dealing with on a daily basis. In recent years, my own social-media feeds seem saturated with news of mass shootings, rape culture, and rising opioid overdoses, with various analyses on the downfalls of neoliberal ideology, and with several sponsored ads for online counselling, because apparently Facebook thinks I really really need it. Given all this, it doesn’t surprise me that millennials are the main consumers of my artwork.

It seems like my generation is always anxious: they’re worried about their daily life, worried about the state of the world, or both. But amid the flood of these troubling topics on my feed, there are also usually several posts about self-care. There are many definitions of self-care, but at its healthiest, the term has been defined as a way to focus on our well-being. It’s a way to recharge our energy for the many causes we have to fight for to make this world an easier, kinder place to live. This is what it looks like to me, online: friends posting on social to remind other friends to stay hydrated and take breaks, you creating reminders to take your antidepressants or chronic-pain medicine, people checking in with loved ones, remembering to breathe, to cuddle pets, to treat themselves. Too often, though, self-care is not promoted as its best version. Mixed into all these good vibes online are a steady flow of ads that push self-care. Apparently, the key to loving myself and healing ongoing trauma is to invest in better hair conditioner, purchase fitness gear to “fix” my lumps and rolls, and buy leggings that promise to reduce cellulite. All these products all seemed to promise solutions that focused less on how I felt and more on how I looked.

The wellness-and-beauty industry has turned self-care into a product you can buy, a solution you can order online for a fee. A simple Google search of “self-care” yields more than 60 million results—and a lot of them are listicles that include the hottest self-care products. I can easily find “9 Self-Care Products for Days When You Don’t Want to Leave Your House,” “19 Items to Buy for Your Mental Health, Because Self-Care Isn’t Always Free,” and “8 Products for Self Care to Help You Make the Most of the Mental Health Day You Deserve.” Products on these lists include a $38 (US) herbal supplement called Moon Juice Brain Dust, a $15 (US) Nooni Apple Water Protective Lip Mask, and a $21 (US) TriggerPoint Massage Ball, just to start.

Sure, there is some truth to the idea that self-care comes with a monetary cost. To stay hydrated, you have to buy water or pay your bills. To rest, you need to own a bed and a blanket, which cost money. To take a warm bath, you have to have paid your hydro bill. To write down your feelings and thoughts about the day, you need to own a journal and a pencil. We live in a world where the essentials are, unfortunately, considered luxuries. And I won’t pretend to be above every listicle mentioned. I love to buy myself Lush bath bombs after a tiring day at work. I love to gift my friends fancy tea so they can enjoy pleasant breaks in their day. And, most importantly, I love to draw, and art supplies certainly don’t come cheap.

When self-care is promoted online with a mélange of luxury beauty products, herbal supplements, and speciality blankets and pillows for meditating, it ceases to be accessible. When self-care is co-opted by capitalism, when it becomes a product, it ceases to become something we all need and deserve. It becomes a luxury for the privileged, a commodity for the people who are probably the least exasperated and exhausted. If self-care is nothing more than getting your legs waxed, your skin brightened, your hair relaxed, your cellulite removed, and your favourite foods replaced with supplements and powders, then it’s also nothing more than conforming to the patriarchal, Eurocentric expectation of how we should look and act.

I believe that we all deserve self-care, but when consumerism and self-care mix, the very idea of us all deserving a break becomes muddied. It becomes difficult to separate it from the oppressive, suffocating, impossible ideals of beauty, luxury, and worth for which we’re all pressured to strive. It becomes not just something you have to purchase but a small reward after a long hustle. If you “kill it,” then you deserve a break—or, say, a gold-infused face mask. But self-care shouldn’t be yet another thing you have to earn. It isn’t a one-time (expensive) reward for hard work; it’s the necessary rest, medicine, and overall wellness that we all need in order to survive.

I want my art to send messages of self-care that are accessible. I like to draw different bodies experiencing joy, community care, and respect. I intentionally draw bodies that defy what we see in commercials, movies, and music videos: fat bodies, brown bodies, Black bodies, disabled bodies, imperfect, scarred, hairy, stretch-marked bodies. I draw images of flowers, animals, cups of tea, glasses of water, medicine, books, and blankets because these things are often more accessible in our daily lives than expensive vacations, lip injections, bubble baths, and bottles of champagne. My messages are not perfect, and they are undoubtedly influenced by my own privileges, but my intention, and hope, is that they will bring solace to people in a way that the sponsored post about the latest brunch place in town cannot.

One of the most common comments I receive on my art is “I needed this.” People tell me they “needed to see this today,” or they “needed to hear this.” Self-care and messages of compassion, empathy, and understanding are things that we do need. To be told you are worthy is necessary. People need to know they are worthy simply for existing as a person. They’re not inherently worthy because they lost weight or did a keratin treatment on their hair or bought underwear that sucks in their tummy. They’re not worthy because they got a promotion or got a boyfriend or went to the gym or were able to afford a designer dress. I want to tell people they’re worthy because they wake up every morning—maybe even when they’re feeling suicidal, sick, or too tired to shower and when they got fired, got dumped, or screwed up big time. I want our worthiness as people to be automatic and not a thing we have to put in a shopping cart.

My only hope for self-care is that it remains a practice that grows from the ground up, not something offered down to us from a pedestal of luxury that most of us can’t reach. After all, we need this.