Before first contact on Turtle Island, we Native peoples were simply ourselves. We, of course, had identities, the names by which we knew, and still know, ourselves: Hopitu, Oceti Sakowin, Kanien’kehá:ka, Powhatan, Chahta, Anishinaabe, Beothuk. Explorers in search of the East Indies landed on our shores in the 1400s and called us “Indians”—a clear misnomer but one convenient lump to be exploited all the same. They bastardized our names to make them more understandable in their own languages of French and English—Iroquois, Mohawk, Coast Salish, Ojibway. None of these are our words or our identities. We have been, and continue to be, defined by settlers.

The continual refusal of Canada to acknowledge our names for ourselves, insisting instead on “Indian,” or later “Aboriginal,” or now “Indigenous,” has ideological roots in the same idea. We name you. We grant you your identity—or not. You are ours to name as we choose. When Prime Minister Justin Trudeau originally announced the split of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada into two new ministries this summer, he admitted the department had been created when Canada’s approach to Indigenous peoples was “paternalistic, colonial.” Canada’s control of us—down to the very names we bear—reflects this paternalism and colonialism in action. The current national confusion around what constitutes Indigenous identity—which we’ve seen play out very publicly at times in a number of different ways, from the debate about cultural appropriation to the scrambling at many organizations to hire Indigenous spokespeople in a kind of retroactive diversity—is the direct result of this painful history. It’s obvious, then, that before we really have a conversation about what post–Indian Act Canada would look like, we need to have a serious conversation about Native identity itself and the ways that Canada’s policing of that identity has historically hurt our communities—and continues to do so today.

Recent identifiers such as “Native American,” “Aboriginal,” and “Indigenous” are deceptively vague, attempting to contain all of the complexities and differences of each individual tribe under one umbrella term. The problem with such terms, of course, is that the bigger the group they attempt to represent, the more they erase complexities and differences and encourage homogenization. While grouping all Indigenous tribes and nations together can be convenient, the reason these terms became necessary in the first place is colonialism. Settler governments needed a term to differentiate us from the settler population (i.e., not indigenous to or claimed by a tribe indigenous to Turtle Island) to figure out how to exactly describe the problem we posed to their burgeoning nation-states. We could not be “The Hopitu-Oceti-Sakowin-Kanien’kehá:ka-Powhatan-Chahta-Annishnawbe-Beothuk, etc. problem.” We must be, simply, “The Indian problem.” Bearing that in mind, the question of how to define Native identity should always be split in two: how the government defines us and how we define ourselves.

As two writers trying to communicate Indigenous realities, we are keenly aware that one of us is Métis and the other Tuscarora. We both live in urban centres. We do not speak for all Native people. To do so would be folly: we reflect different lived experiences with ancestors that come from different parts of this land, practicing a multitude of ceremonies, traditions, and ways of storytelling. Similarly, the appointment of one Indigenous person to a corporate board or news department should not make that individual responsible for reflecting all Native views, experiences, or knowledge. That would be tokenism, and it does not absolve settlers from respecting and researching specific and diverse Indigenous realities.

Some of the things we, as Métis and Tuscarora people, do have in common with other Indigenous tribes and nations is that our ancestors were here before colonizers, we have all suffered from colonization, and we continue to fight against that reality daily.

The term “Indian” has a long history in this country, first appearing in legal documents in the Constitution Act of 1867 to give Canada legislative jurisdiction over “Indians and lands reserved for Indians.” This was the legal precedent for describing numerous distinct Indigenous nations as one homogenous group—and also the model for the paternalistic relationship Canada continues to force upon Indigenous peoples, stripping us of our ability to make decisions for ourselves.

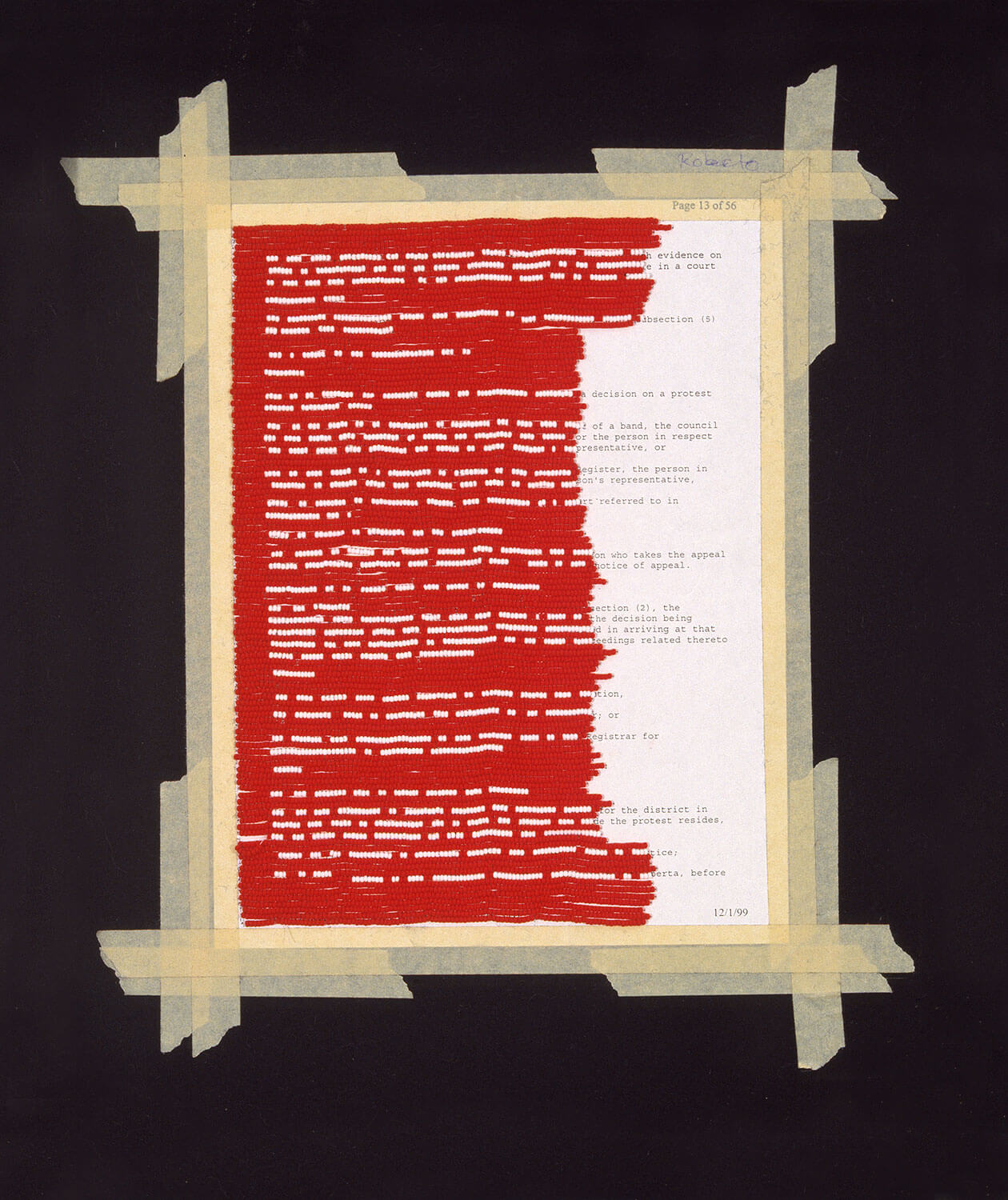

This became further entrenched when the Indian Act was passed under Prime Minister John A. Macdonald in 1876. According to Canadian law, an Indian was defined as “any male person of Indian blood reputed to belong to a particular band,” “any child of such a person,” or “any woman who is or was lawfully married to such a person.” In this way, Canada both systemically discriminated against Indigenous women and forced the lineage of Indigenous people to pass patrilineally, which greatly impacted those nations that traditionally passed on their nations and clans to their children matrilineally. The Indian Act also renamed Native tribes with easier-to-pronounce European names, called them “bands,” established reserves, forcibly installed their own governance systems, called “band councils,” on those reserves, and introduced the residential school system. Every line of the Indian Act was written with the express purpose of assimilating Indigenous peoples, destroying their cultures and languages, and extinguishing their treaty rights—and all of that depended on Canada defining who was and wasn’t Indian.

Like the legal term “Indian,” “blood quantum” is another colonial construct. It’s a unit of measure that determines how Indian you are based on the number of ancestors you have who are “full-blooded” Indians. Unlike the infamous American one-drop rule, which legally classified anyone who had one black ancestor—or “one drop” of black blood—as black, and thus ensured more people were deemed slaves, and later, more people forced into a lower racial stratification, the goal of blood quantum was to ensure fewer Native people. The more Indigenous people married out and had children with non-Indigenous people, the fewer “real” Indians there were—and the fewer “real” Indians there were, the easier it was for the government to deny treaty rights and obligations. Blood quantum turned Indigenous peoples’ tribal identities into a de facto race that the government could now measure in percentages and slowly, methodically legislate away.

One problem with that system, of course, is that Indigenous peoples never relied on blood quantum to determine tribal membership before contact. Many nations, like the Haudenosaunee, for instance, adopted members of other nations or tribes into their own to replace deceased family members. It was a useful strategy to keep the nation strong. In that sense, it’s more accurate to think of Indigenous nations as countries than to think of them as a race. As with any sovereign country, each Indigenous tribe or nation has its own ways of determining membership. Just as a Canadian citizen wouldn’t say she is 25 percent Canadian, a Mohawk person wouldn’t traditionally say she is 25 percent Mohawk. Similarly, just as one isn’t necessarily a German citizen because one has a great-great-grandparent who was a German citizen, one isn’t necessarily Anishinaabe because one has a great-great-grandparent who was Anishinaabe. Focusing on percentage to determine Native identity is a deliberate attempt by historical Canadian and American governments to both force Native people to assimilate into their own national populations and to delegitimize Indigenous nations’ sovereignty.

It’s a testament to the effectiveness of colonialism that DNA tests and blood quantum continue to hold sway in national conversations on Indigeneity. With the rising popularity of sites like ancestry.com, many non-Native people have been eagerly looking for connection, however weak, to a long-forgotten or rumoured Native ancestor. These controversial DNA tests have framed the dubious basis for non-Natives to justify their appropriation of Native culture, land, and resources.

Kim Tallbear, a Dakota scholar based at the University of Alberta, has been studying the phenomenon of DNA and Native-identity claims for years. While Tallbear admits umbrella terms, including “Indigenous” or “Native American,” help us “talk to one another, relate to one another,” generalized “Native” genetic markers lack specificity. There are over 600 Indigenous communities in Canada. If your DNA test says you have 15 percent Native American DNA, for example, what community would that mean your ancestors came from? What would that mean if you had no lived experience with that community? According to Tallbear, Native peoples “construct belonging and citizenship in ways that do not consider these genetic ancestry tests. So it’s not just a matter of what you claim, but it’s a matter of who claims you.”

The Canadian government’s approach to Indian identity has always been selective and inconsistent. Its categorization of Native peoples, which includes status Indians, who receive ever-diminishing benefits, as well as non-status Indians, Inuit, and Métis, allows the government to maintain control over Indigenous peoples and their lands, including the profits made from natural resources.

Experts in the field of Métis research—such as Chris Andersen, a Métis professor, dean of the Faculty of Native Studies at the University of Alberta, and author of “Métis”: Race, Recognition, and the Struggle for Indigenous Peoplehood—have thoroughly recorded the story of the Métis as separate from those of other Indigenous groups because they are an Indigenous nation that developed post-contact through marriages between Native and non-Native peoples. The Métis Nation is rooted in the Canadian Prairies, with a distinct culture, history, and language. For many people, the term “Métis” gets confused with the French word métissage or métis (small m), which literally translates to “mixed.” This erasure of this Indigenous nation’s meaning perpetuates the colonial method of control. Identifying as métis has also been used to excuse or allow for racism, i.e., “I’m métis—therefore I can speak with authority about Native people.” The word métis becomes a catch-all that allows non-Indigenous people to appropriate Native identity while ignoring the complexities of tribal history, identity, and responsibility. This confusion has not been helped by the federal government, who neither included Métis in the Indian Act nor considered them a federal responsibility.

That all changed last year with the Daniels decision, in which Métis and non-status Indians were officially recognized as “Indians,” and therefore fall under the federal government’s jurisdiction in s. 91(24) of the constitution: Canada must now consider Métis and non-status Native issues when legislating, as well as relate to each on a nation-to-nation basis when it comes to rights and claims. However, this decision does not deem Métis and non-status Natives as “Indians” under the Indian Act, so they aren’t eligible for tax exemptions or other benefits retired provincial-court judge Brian Giesbrecht has gallingly referred to as “the gravy train.”

As Saint Mary’s University professor and “settler self-indigenization” researcher Darryl Leroux has pointed out, this hasn’t stopped groups from popping up to claim Native ancestry and identity in misguided attempts to board this mythical gravy train. The Mikinaks are one such group—a self-proclaimed Aboriginal community based in Quebec’s Montérégie region, it requires $80 and proof of any Indigenous ancestry in order to bestow membership. In exchange, recipients given a photo ID that looks similar to government-issued Indian Status cards. Mikinak “Chief” Lise Brisebois has said that even if a member’s Native ancestor is “eight generations back, that’s okay. The most important thing is that you feel it inside you.” This method of ascertaining tribal citizenship relies on romanticized stereotypes and emotions in place of actual acceptance by an Indigenous community.

Scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang have called out these “settler moves to innocence” where white colonizers either deem themselves Native through distant ancestry or through acceptance into a Native tribe as dramatized in films such as Dances With Wolves, Little Big Man, and Avatar, among other examples. Settlers position themselves as Indigenous, absolving themselves of the national history of genocide while simultaneously suggesting ownership of the land. This usurping ultimately decentres and erases Native people from their own land, history, and culture, situating white settlers as more deserving of being Indigenous than Indigenous peoples themselves. Once erased, actual Native peoples are no longer a barrier to resources, land, and culture.

If our identity can be so easily adopted, how do we ensure we are who we say we are? The best way is to let us define ourselves. We have our own ways of relating to one another and determining tribe, nation, clan, and community. And when we ask one another, “Where are you from?” or “Who claims you?” it’s not an attempt to police identity or alienate, it’s an acknowledgement of the importance of community. The answers to these questions situate each of us firmly within the extensive kinship networks inside our communities—networks that provide support, ceremony, and tradition. These relationships are how we maintain our oral storytelling, traditional knowledge, dances, songs, languages, and so on. Without them, we would not be able to tell our people’s stories or pass them on to the next generation. Kinship is our legacy.

Canada’s new buzzword has become “reconciliation,” but many Canadians may have no idea of what that process looks like in their everyday lives. It becomes much easier to imagine when you divide your responsibilities up and examine reconciliation on both a civil and personal level. Canadians can encourage their federally elected leaders to actively comply with all ninety-four of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action, to start, and then encourage them to fully implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (often referred to by its acronym, UNDRIP). Canadians can support federal efforts to fund the full restoration of our endangered languages and demand that governments respect our right to decide what happens on our land. Voice your expectation that your elected officials resolve all outstanding land claims in a manner that respects all involved.

On a personal level, the most important thing Canadians can do is educate themselves more regarding Indigenous realities. While the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report is indeed intimidating, at more than 900 pages it’s still shorter than the most recent book in the A Song of Ice and Fire series. Plus it’s very well written, surprisingly readable, and free to access online. Committing to reading a little bit every week shows that you want to be not only an active participant in reconciliation but also a more informed citizen. You can take a free online course provided by the University of Alberta called Indigenous Canada. Other essential things Canadians can do: Learn the treaty history of the lands that you live on. Learn how to say the names of the Indigenous nations who traditionally cared for those lands—in their language. Teach these lessons to your children. If you’re a member of the media, make it a priority to be properly educated around topics that concern Indigenous communities so that you can write responsibly and avoid perpetuating harmful myths.

Knowing what mistakes Canada has made in the past, why they were mistakes, and, most importantly, how they have shaped our present, will ensure that we stop paternalistic, colonial patterns from repeating. It will ensure that fifty years from now, our own descendants won’t have to look back on our actions and feel ashamed, clumsily claiming we shouldn’t be judged so harshly because we “didn’t know any better.” We do know better. We have known better for years.

It will take all of us to reconcile our collective past, and the process will be difficult. But it’s a necessary step on our path to create a newer, better course for our collective future.