In september 2016, I accompanied my father, Tony Urquhart, to the Art Gallery of Ontario, in Toronto. We’d been at a memorial service for a family friend that morning, and we were spending the afternoon touring the gallery. My father, who was then eighty-two and has had white hair for as long as I can remember, guided me to a collection of Canadian postwar paintings on the second floor. As we stood in the centre of the room, he asked, “Do you see any of your friends here?”

Sometimes I can identify the hands behind the brush strokes, but that day, I was uncertain. My father opened the catalogue to the page referencing the east wall and ran his finger across the list of paintings and their makers until he came to rest on his own name. The Earth Returns to Life (1958), by Tony Urquhart, born 1934.

“No death date,” he said. “I’m the only one still alive.”

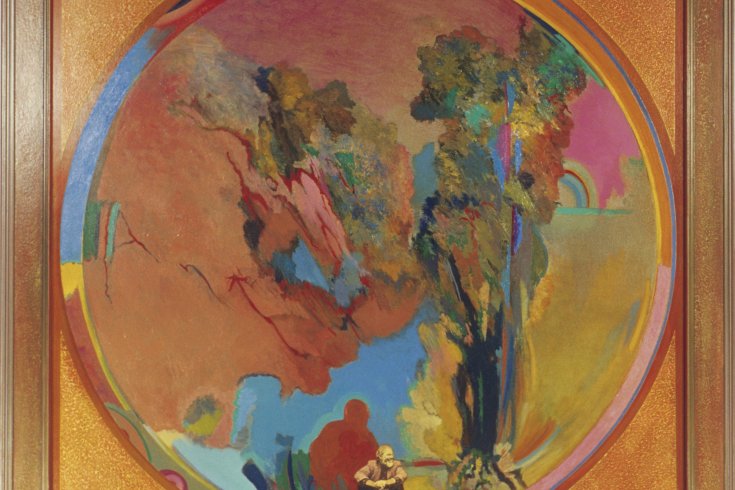

The painting was completed in my father’s final year of art school, when he was twenty-four. It’s a landscape in oil, with an atmospheric background and otherworldly organic matter. Patches of earth, frothy water, trees, and roots have all been tossed apart by some unseen natural force. The work has the kind of frenetic energy we associate with youth, and it hints at his later and better-known abstract expressionist paintings that are now in collections across North America.

My father is a remarkable painter, and this was clear even from an early age. At twenty-three, he’d already had his first one-man show at Toronto’s famed Isaacs Gallery; in Painting in Canada: A History, published in 1966, he was referred to as a “child prodigy.” But as we stood in front of The Earth Returns to Life that September day, he had his own choice words about his painting: it was immature. He told me that he’d rather see one of his later pieces displayed in the AGO, to better represent the peak of his painted work. He even had one in mind: Allegory. It’s a mysterious tangle of earth and weed set in a deep blue fantastical landscape. It was completed in 1962— when he was still a young man, though less so.

I understood my father’s position, though I thought he was wrong about Allegory. Like many of his other early to mid-career works, it’s a fine painting. But I’d argue that now, as my father is in his ninth decade, he has honed his skills, and his art has reached its zenith. I may be biased, but I’d say his recent works show a powerful coupling of intellect and experience. Young Tony Urquhart was undoubtedly gifted, but senior Tony Urquhart, at an age when we expect artists’ careers to fade and their output to end, is constantly surprising me with the unpredictable, often astounding ways he sees the world.

My father’s large-scale oils from the 1960s to the 1980s were earth-toned abstractions inspired by the European countryside. Spooky shapes were often foregrounded by a hovering darkness. These were the products of uneasy times: Canada was on the fringes of the Cold War, and his art was imbued with nuclear threat. That changed when he entered his sixties. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, freed from those earlier anxieties, vibrant, almost supernatural, colours appeared on his canvases in a series of self-portraits called My Garden. The tension of his earlier work remained, but the mood had lifted. Where there had been foreboding, there was now intrigue. Something spiritual glowed on the horizon.

Perhaps the best example of his new vision, though, is Strong Box I (2013), the first of a recent series. The painting shows a central peach-hued rectangle bracketed by a pinkish red so intense it seems backlit. The repeated rectangular shapes are ambiguous, suggesting a cage or a series of rooms— familiar territory for my dad, as is the marbleized effect of the blended background colours and the mottled balls of organic matter that cling to the four corners of the painting’s sharp, straight lines. But the colours— that pink!— are new, and they are electric. Just shy of his eightieth birthday, he’d imagined and executed something novel.

We tend not to associate aging with creative bursts. Historically, critics saw advancements by elderly artists as peculiar. According to twentieth-century art historian Kenneth Clark, the work of older artists conveyed a feeling of “transcendental pessimism,” best illustrated in the weary, lined eyes and pouched cheeks of Rembrandt’s late self-portraits. Claude Monet’s contemporaries decried his Water Lilies series as a symptom of cataracts and advanced age. The paintings were dismissed as “the work of an old man” in Comœdia, France’s most important daily arts journal at the time. Fellow painter André Lhote described them as “artistic suicide.” In J.M.W Turner’s final two decades, as he painted rain, steam, and speed in his increasingly abstract landscapes, he found himself brutalized by peers— a kind of aesthetic elder abuse. Turner was “without hope” wrote John Ruskin. Another less tactful critic said that Turner’s late work was the product of “senile decrepitude.”

Many older artists, however, sense the significance in their new creations, even if the public reacts with hostility. In the eighteenth century, Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai, known for his Great Wave woodblock print, claimed that everything he’d “done before the age of seventy is not worth bothering with.” Above a black chalk drawing of a formidable old man propped on two walking sticks, wild-haired and defiant, an eighty-year-old Francisco Goya inscribed: “I’m still learning.” And he was; Goya was in his seventies when he mastered the emerging process of lithography.

“Now it’s recognized that there was not a falling off of creative powers [as an artist ages] but that their creative powers have changed,” says Ross King, author of Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies. “They were deliberately working in different ways.” One brush stroke from Monet— a silhouette of a petal at dusk— holds all the shadow, richness, and texture of a life as a painter. But this is something that people often overlook. Today, it’s doubtful that most gallery patrons know that Monet was in his seventies when he created the most famous paintings in his Water Lilies series. Turner’s late creations are now widely recognized as works of incomparable brilliance. The same could be said of art from Paul Cézanne, Titian, Michelangelo, and Rembrandt.

We have been conditioned to think that age is a barrier to creativity. But, in reality, it is ageism that can be stifling. As legions of baby boomers tilt toward their third act, the old artist will become less of an outlier. It’s time to rethink creativity as the realm of the young and embrace Carl Jung’s statement that “the afternoon of human life must also have a significance of its own and cannot be merely a pitiful appendage to life’s morning.” Our lifespans elastic, our twilights are stretching. For some artists, the finale will be the best part of the show.

Amore recent argument that older people are less creative than the young can be traced back to Age and Achievement, a 1953 book by psychologist Harvey C. Lehman. He tracked artistic success in various disciplines over five-year periods and concluded that each art form has its own unique decline corresponding with age. Poets peaked in their mid-twenties, classical composers and painters withered in their thirties, and prose writers prevailed, if they were lucky, into their early forties. Old artists may possess wisdom, Lehman conceded, but their best work was behind them.

New research contests Lehman’s methods and theories. His critics say that he drew conclusions based on citations in art-history books and encyclopedias— texts written by the same gatekeepers who dismissed Monet and Turner as useless geezers. (Women and people of colour were also largely absent from these books; therefore, much of the population wasn’t even considered.) In the late 1960s, psychological researchers discovered that older people are actually brimming with cumulative wells of skills, knowledge, techniques, and style attained over their lifetimes. Still, the damage from Lehman’s book was done, and his thesis still pervades our popular culture. A 2017 article about genius in National Geographic featured an infographic drawn from Lehman’s study.

“There are two very different kinds of creativity,” says University of Chicago economics professor David Galenson, author of Old Masters and Young Geniuses: The Two Life Cycles of Artistic Creativity. One type, Galenson explains, is a “conceptual innovator,” a person who works from a single idea. These people tend to be radical: they may draft a quick sketch of a concept, and then, almost immediately after, assemble a masterpiece (consider Pablo Picasso and his Les Demoiselles d’Avignon or Andy Warhol’s screen prints). Then there are “experimental innovators,” who progress incrementally, learning with each sketch and layer of paint. These people often work on series and angle toward an ideal vision that can feel just out of reach— think Rembrandt’s late self-portraits and the 250-odd paintings that make up Monet’s Water Lilies. Galenson’s theory applies to the artist’s process, but he also noticed a second trend: “There’s a tendency for conceptual innovation to come early and a tendency for experimental innovation to come late.” The idea that creativity declines with age is, in Galenson’s opinion, “just wrong.”

There is a theory concerning a shift in technique, medium, or scale that can occur in an elderly artist’s work. It’s called Altersstil, or old-age style. Some art historians, Kenneth Clark among them, claim that the same old-age style characteristics appear across different forms and genres: an aging artist’s work is seen by experts as increasingly abstract, spiritual, or ethereal, and the blurring of formal and informal styles is described as a nod to eternity.

But others in the art world say the idea that formal attributes can correspond with a creator’s age is absurd. Galenson, for one, finds the idea ridiculous and ageist. “I mean, is there a middle-aged style?” he asks. This school of thought argues that there are no definitive attributes that characterize late-stage creativity: yes, Monet, Rembrandt, and Goya were all geniuses in their later years, but each in their own incomparable ways.

A sudden bolt of brilliance late in an artist’s life is something that has been repeatedly documented. The author of a 1989 study published in the journal Psychology and Aging looked at more than 1,900 works by nearly 200 classical composers and identified what he termed the “swan-song phenomenon”— a burst of creative output in the final stage of life that is often considered the musician’s best work. Richard Strauss composed Four Last Songs as his finale. It is my father’s favourite piece of music. I once asked him to describe it to me. “I can’t,” he said, his eyes welling with tears.

The crowning example of a swan song in visual art may be Monet’s Water Lilies. “He was an old man in a hurry,” says King. “I guess that’s one of the things you do when you get older— you begin thinking about posterity and also wanting to make an artistic statement. You don’t have decades left and, therefore, you have to synthesize what you’ve learned and create a final masterpiece or series of masterpieces.”

Consider Nunavut-based artist Elisapee Ishulutaq, whose drawings and prints depict life in the Arctic. Her early works were typically smaller than two by three feet. Then she learned to use oil sticks, and her canvases expanded. She began working in a drastically different scale when she reached her mid-eighties. In a 2010 review, Georgia Straight visual-art critic Robin Laurence wrote, “The oil stick medium seems to have given the octogenarian Ishulutaq licence to bust out of all constraints of colour, form, and scale.” In 2016, at ninety-one years old, Ishulutaq created her largest work to date. In His Memory is a four-panel oil-stick drawing that stretches thirty feet. It’s a monumental work to honour a harrowing event: the paintings depict the aftermath of a young boy’s suicide in the 1990s and its impact on Ishulutaq’s small Arctic community. In the third panel, small brightly jacketed people retreat from a modest cairn topped with a cross. Two members of the group, a young child and an adult, reach for each other. It’s a small gesture of hope, writ large.

Not all older artists have the same opportunities to show their work, however. And if we don’t check our biases, their art might be lost to obscurity. This is particularly true for women who’ve sharpened their skills over decades. In some cases, their creative work was done while caring for their families or tending to a husband’s larger artistic ego. The belated critical acclaim for artist Sonia Delaunay, whose colourful geometric abstractions cross the boundaries of fashion, decorative art, and visual art, serves as an example. Her husband, pioneering abstract expressionist Robert Delaunay, died in 1941, and it was only after this that Sonia was recognized as a serious artist in her own right. She was celebrated in 1964 with a one-woman show at the Louvre— the first for a living woman— when she was seventy-nine. Cuban-born American painter Carmen Herrera was 101 when she had her inaugural solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2016. It focused on her work from 1948 to 1978, and included many pieces that she created in her fifties and sixties. Herrera, however, only made her first sale after she turned eighty-nine.

“The art world finds it very hard to accept older artists if they’re not already well known,” Galenson tells me. He argues that more resources, such as prizes and grants, should be focused toward older artists. “It’s not just from an equity point of view, it’s not just about fairness,” he says. Rather, it’s about “making our society as creative as possible.”

Prompted by our conversation at the AGO, I visited my father over the next three seasons and we spoke about the past, present, and future of his creative work. We sat together in the drawing room of my parents’ home in Colborne, Ontario, where pens are corralled in silver soup tins on his desk and jars of black ink line the windowsill. His newest creations—cactus-inspired mixed media on paper—were stacked in modest piles along the seat of a high-backed sofa that was made by our undertaker ancestors (furniture making being a natural side business). His record player and extensive collection of classical music occupies the space to the left of his desk. A ticking clock keeps a background beat to his days.

This room has become his world. He has mostly abandoned his current painting studio, which is poorly heated and cramped compared to the barn-like structures he occupied during the years of my childhood. Those cavernous spaces aren’t really necessary now. In the past decade, my father hasn’t been able to lift the large canvases that he previously worked with, some of which reached ten feet long. His newer paintings are smaller and fewer. But his technical skills remain sharp; his weird sense of the world, attuned; and his work ethic, unwavering. He continues to make art every day. “You have to work hard at it,” he told me. “It’s like sports— you can’t sit around and then do your best score at the golf course. You’ve got to be doing it all the time.”

I asked him if he felt that his greatest creation might still be ahead. He isn’t sure, but he doesn’t rule it out. “It would be nice to think that the best painting I’m ever going to do is still waiting to be done, but I have a hunch that that won’t be the…” he trailed off, glanced at a pile of drawings. “The best work on paper might be,” he said. “But you can’t will a masterpiece.”

Above where we sat, on the top row of the bookshelf along the east wall, there is a line of fraying red Michelin travel guides to Europe, evidence of past artistic journeys. France, 1958: his first trip to the continent. It was just after he had painted The Earth Returns to Life, and during the voyage, he underwent what can only be described as an aesthetic conversion, brought about after seeing the Roman Catholic churches— flickering candles, the solemnity of High Mass, the gilded and the golden, the frescoes— paleolithic cave paintings, and, the crowning event, master draughtsman Goya’s drawings in the Prado archives during a jaunt to Madrid. Deutschland, 1967: stationed in Dublin for the summer, he took a short trip to Bavaria with his then wife and saw the pilgrimage churches and their triptychs and diptychs. He returned home, and, using a sabre saw, he pried apart the sculptures he’d been creating. He then made doors to form curio cabinets that opened to reveal three-dimensional landscapes. He calls them, simply, boxes. The most recent, finished this past spring, is speckled with tiny pebbles from Middle Cove Beach that we’d gathered together when I lived in Newfoundland. Inside, antique keys hang like bats in the crevices of a cave.

Aging, however, does change the reality of being an artist. In the last decade, there have been several long gaps in the string of Michelins on my father’s bookshelf. Suitcases must be lighter now and can’t contain art supplies when going over or gallery catalogues when coming back. Travel itself can be exhausting.

Another recent issue for my father is that his ideas can be elusive. They come, but, almost as quickly, they go. His “idea books,” which is what he calls his small portable sketch pads, now double as a kind of aide-mémoire. “The notes are in the drawings and in the paintings, and that doesn’t change,” he said. “You may add to it, but, nevertheless, it’s there, literally in black and white.”

The notes are also on the wall. My father has always kept a corkboard across from his place at the kitchen table. He pins up unfinished drawings, which he then surveys while eating. “It happened this morning,” he told me one afternoon in mid-August. He showed me a black-and-white pen-and-ink sketch of a split-rail fence. It had been pinned to the board for six months, but today, something in it had sparked plans for a new painting. “While I was sitting there eating my breakfast, I kept seeing it,” he said. “I kind of had the idea, and I think it will work.”

There is a missing chorus in this story: the voices weakened by frailty and hampered by failing senses. In the process of researching late-stage creativity, I set up several interviews with artists who are over eighty, but for whom the realities of aging ultimately made meetings impossible. They were still making art, their gallerists and caregivers assured me, but age intrudes. It happened to them as it happened to Georgia O’Keeffe, Edgar Degas, and Monet, all of whom experienced vision loss in their later years. Each of those artists continued to work, but, as Degas said, “Everything is trying for a blind man who wants to make believe that he can see.”

My father doesn’t know if he’ll see the art he’s creating today displayed, purchased, or revered in his lifetime, but it’s possible. Based on the recent successes of older artists, such as Herrera, it seems that the art world’s gerontophobia is poised to shift— and maybe, based on demographics, that’s inevitable.

Last year, Britain’s prestigious Turner Prize got rid of its age limit, previously set at fifty, and is “acknowledging the fact that artists can experience a breakthrough…at any age.” Eighty-eight-year-old Yayoi Kusama, arguably the most successful living artist in Japan, opened her own museum in Tokyo this fall. A quick survey of exhibiting Canadian artists who are over eighty include Ann Kipling, Mary Pratt, and Rita Letendre, who was the focus of a recent solo exhibit at the AGO.

So far, aging hasn’t kept my father from making art, but it’s something that he fears could come to pass. “I think about that occasionally and then promptly forget it because it would be terrible,” he told me, adding that he’s following a strict regime— plenty of water, a good night’s sleep— in an effort to maintain his working life. “I enjoy it as much as I ever did,” he said. “I’m still discovering things.”

Take, for example, the genesis of Strong Box I. Five years ago, when he was seventy-nine, my dad visited me in Victoria, British Columbia, where I lived for a time with my husband and children. In the past, rain or shine, he would leave our house to ramble, perhaps discovering a grouping of oddly pollarded trees or some vegetation germinating on a tombstone to sketch. On this trip, though, he remained in our living room. There, he spent several dark winter days drawing a battered First World War chest that we’d inherited from my husband’s family and used as a coffee table. I was surprised by his interest in the trunk, but even more so by his reluctance to leave the house and explore the outdoors, which has long been his muse. Months later, when I visited my parents in Ontario, the trunk was there, immortalized in an oil painting hanging above the fireplace. The trunk’s worn, brown patches were converted into rose, fuchsia, and vibrant blues, my living room eclipsed by a fiery-red background. And that fluorescent-pink was at its centre. The trunk was still familiar, as was my father’s style, but both appeared to be transformed.

“What is it about the trunk, Dad?” I asked.

“I don’t know why I like that trunk,” he said, shrugging.

I think I know the answer. As a younger man, my father found inspiration for his large-scale oils by trekking across European landscapes and into the dark flicker of far-flung churches. Those destinations are now unreachable, but there is one place that remains accessible to him: the terrain of his imagination.