The two cowboys in Jim French’s illustration Longhorns—Dance make an odd couple. The one on the left has dark shades and an open denim jacket. He looks cool and mean, like Clint Eastwood in the Dollars trilogy. The one on the right is adjusting the cool one’s neckerchief. He is baby faced and blond, a cherubic Billy the Kid. Both wear Stetson hats and are naked from waist to boot. Their cocks—as long and heavy as the gun in the cool guy’s holster—are facing each other, the heads almost touching. What brought these men together? Are they doing something they’ve done before or experimenting with a new kind of intimacy? Who knows? They are cowboy archetypes rather than fully fledged people. Their backstories are whatever you want them to be.

French sold his drawing in 1969, but it keeps resurfacing. In the mid-’70s, it appeared on a T-shirt by punk-rock designers Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood. And, in 2019, it showed up in “Hope to Die,” a music video by the Toronto-based country singer Orville Peck, which opens with a still shot of two cowboys standing face to face. This time, the cowboys keep their dicks concealed—a concession, no doubt, to YouTube community guidelines—but the poses they strike and the clothes they wear are unmistakable: they are incarnations of French’s characters.

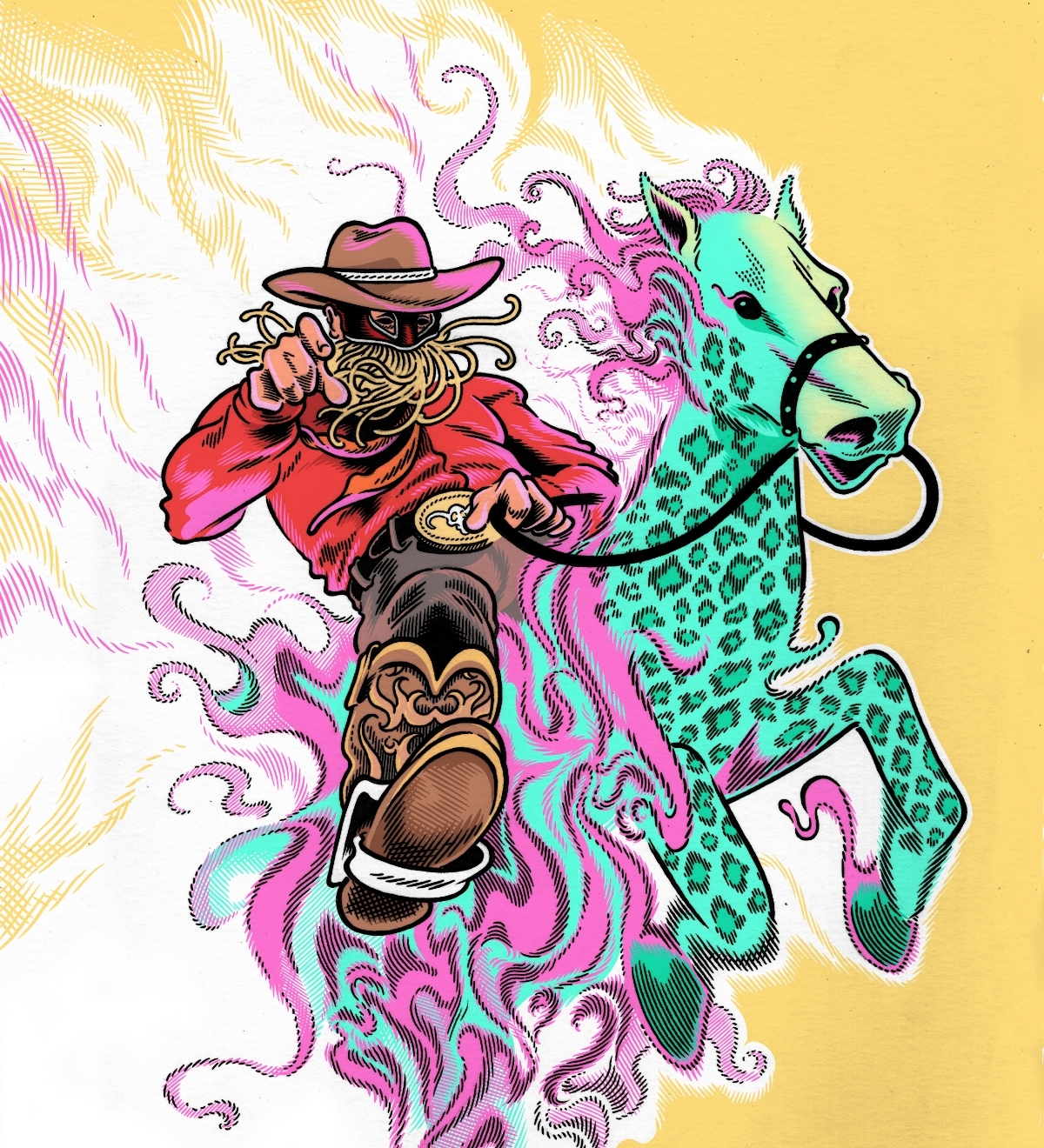

The guy on the left is played by Peck himself, who, like the cowboys in the original illustration, is a persona rather than a person. (Many music fans know his real name, but it hardly matters.) In concerts and videos, he appears in different versions of the same outfit: belts with chunky buckles, boots with rhinestones, patchwork jeans, or colourful Nudie suits—those flamboyant pants-and-jacket ensembles beloved of Elvis Presley and Gram Parsons. Peck never shows his face. Over his eyes, he wears a black bandit mask fringed with tassels, which cover his mouth and neck. His voice is a mournful baritone reminiscent of Roy Orbison’s, and his music is classic country with elements of gospel, rhythm and blues, rockabilly, and punk.

More than the costumes or the eclectic songs, it is Peck’s storytelling—tales of derring-do, heartache, and forbidden love in the Old West—that sets his work apart. His first album, Pony (2019), features noirish ballads like “Dead of Night,” the saga of a gay Bonnie and Clyde evading law enforcement under cover of darkness, and “Big Sky,” about a cowboy drifter who falls in love with a series of itinerant women and dangerous men—a boxer, a jailer, a rodeo king.

His second album, Bronco (out April 8), covers similar themes but with a glossier sound and a greater degree of emotional vulnerability. In “C’mon Baby, Cry,” Peck counsels a lovesick buddy to drop his inhibitions and give voice to his pain. (“I can tell you’re a sad boy just like me. Baby, don’t deny what your poor heart needs.”) And, in “The Curse of the Blackened Eye,” Peck explores the bitter aftermath of a toxic relationship. After a breakup, the biggest obstacle to happiness “ain’t the letting go,” he sings, “but the things that you take with.” In the video, he is followed around by a demon in a black duster—a shadowy embodiment of the ex-lover, played by Norman Reedus, of The Walking Dead—who sidles up to him at bar counters and slips into his bed. Being heartbroken, Peck suggests, is a bit like being haunted: you sense an absent presence everywhere you go.

Peck is himself a kind of absent presence, a masked cipher, which hasn’t stopped him from becoming famous. In the last two years, Peck has collaborated with Shania Twain and celebrity drag queen Trixie Mattel, performed at Madison Square Garden alongside Harry Styles, and covered Lady Gaga’s queer anthem “Born This Way” as part of an official rerelease of her beloved second album. Critics have praised him fulsomely, if somewhat repetitively, for “queering” country music (Xtra Magazine), “subverting” it (Playboy), and “redefining” its “heteronormative” conventions (Hollywood Insider).

I’m not sure what to make of these statements. The problem with verbs like “queering” and “subverting” is not so much that they’re stilted—the language of cultural studies and the academy—but rather that they’re inaccurate or at least inapt. They imply that Peck is adapting a rigidly straight subculture and making it queer. But is this really true? Haven’t country music and the Old West been a little bit queer all along?

Last February, on the podcast WTF with Marc Maron, actor Sam Elliott, a mainstay of Western movies, tore into Jane Campion’s Oscar-winning film The Power of the Dog, which tells the story of a fraught, erotically charged friendship between a young medical student and a wealthy ranch owner. “There’s all these allusions to homosexuality throughout the fucking movie,” Elliott complained, implying that Campion’s subject matter was somehow anachronistic. If anybody was guilty of anachronistic thinking, though, it was Elliott, who perhaps knows less than he thinks he does about the period in which Campion’s film is set.

When midcentury sexologist Alfred Kinsey began researching his classic study Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male, he noted that homosexuality wasn’t only—or even mainly—an urban phenomenon. “There is a fair amount of sexual contact among the older males in Western rural areas,” he wrote. “It is a type of homosexuality which was probably common among pioneers and outdoor men in general. Today it is found among ranchmen, cattle men, prospectors, lumbermen, and farming groups.” The rigours of the homesteading or ranching life, Kinsey theorized, made people adaptive and practical, open to whatever sexual experiences they could get.

Historical research has since confirmed Kinsey’s hunch that this culture of experimentation went back decades. On the nineteenth-century frontier, people attended dances in drag. Butch women were legendary sharpshooters. Trans men worked as bartenders. And property owners allowed miners or ranchers in their employ to cohabitate—and even unite in so-called bachelor marriages—likely because they needed the labour. The “lawless West” was experimental precisely because it was lawless—a world sufficiently removed from metropolitan norms that it could invent norms of its own.

Is it any surprise that these norms began cropping up, albeit indirectly, in early country and western music? The Sweet Violet Boys’ 1939 song “I Love My Fruit” was a cheeky paean to eclectic appetites and sensual pleasures. (“I am always hungry for bananas,” the lyrics go, “so that it almost seems to be a sin.”) And, while Wilma Burgess’s songs of loss and longing never explicitly addressed her lesbianism, they rarely precluded such a reading either. When writing about love, she avoided gender-specific pronouns, enabling listeners to interpret her work in relation to her identity, which was an open secret in the industry.

Even when it wasn’t trafficking in innuendo, country music was often flamboyant in ways that read as queer today. Watch Gene Autry, with his elaborately embroidered pants and shirts, performing “Back in the Saddle Again” in the 1941 movie of the same name and notice how the men around him—like the singing-competition host who rushes to him and holds a microphone solicitously to his lips—all seem to bask in his glow, thrilled just to be in the presence of a cowboy dandy. Or notice how Western movies often fixate on depictions of male physicality—the hoedowns, the rodeos, the choreographed brawls where bodies lunge and limbs flail as in a Théodore Géricault painting.

The country and western genre was not only campy, though; it was also versatile. It has roots in blues music, Appalachian folk songs, and the cowboy traditions of the West. Its epicentre was Nashville, which produced the slickest, most radio-friendly hits. But, as journalist Kelefa Sanneh notes in his book Major Labels, the movement evolved via a tug-of-war between factions: the corporate Nashville establishment versus the many nodes and hubs that sprang up elsewhere. “Often, the most popular country acts,” Sanneh writes, “have defined themselves in opposition to one or another perception of the genre’s mainstream.”

As country music drew talent from beyond its Tennessee nerve centre, its style and subject matter inevitably broadened. In the ’60s and ’70s, outlaw-country artists like California’s Merle Haggard and Texas’s Waylon Jennings wrote songs about drug use and criminality, undermining Nashville’s milquetoast norms, until, in time, Nashville came to embrace both men as heroes. The story of Lil Nas X—the gay rapper whose 2018 trap-country single “Old Town Road” spent a record nineteen weeks atop the Billboard Hot 100 chart—basically mirrors that of Haggard and Jennings. At first, he was an outsider: Billboard editors removed “Old Town Road” from the Hot Country chart, deeming the song more rap than country. Then, suddenly, he was the ultimate trendsetter. Today, nobody in the Nashville establishment is at all surprised when the industry’s biggest stars—white men like Morgan Wallen or Sam Hunt—collaborate with rappers or incorporate hip hop rhythms into their songs. The genre is absorbing hip hop and trap just as quickly as it subsumed disco in the ’70s or alt-rock in the ’90s.

Even before “Old Town Road,” this push and pull between the margins and the mainstream left just enough space for candid explorations of queerness. “Cryin’ These Cocksucking Tears,” a 1973 single by Patrick Haggerty, frontman of the Seattle band Lavender Country, explores the frustrations of a gay man who’s dumped and ignored by a closeted partner. “Miss Chatelaine,” a 1992 country-cabaret mashup by Alberta’s k.d. lang, alludes to lang’s surprise, as a butch lesbian, at finding herself on the cover of Canada’s leading women’s magazine. And Ned Sublette’s 1981 single “Cowboys Are Frequently, Secretly Fond of Each Other,” later recorded by outlaw-country legend Willie Nelson, explores the same Western world that Kinsey had encountered decades earlier. The lyrics are bracing for their psychological realism. They tell how forbidden love can turn to shame and how shame, in time, can turn to hatred and violence.

None of this is to say that country music culture was uniquely tolerant. The industry could be downright homophobic: after coming out in 1992, lang was effectively exiled from Nashville. The point, rather, is that country had always been eclectic, and its thematic preoccupations—individualism, romantic turmoil—made it ideal for explorations of difference.

This dynamic partly explains why queer musicians today, like Brandi Carlile and Brandy Clark—and, of course, Lil Nas X—are drawn to country. It also explains why Jim French was interested in the cowboy archetype and why, for that matter, Orville Peck was interested in Jim French. By opening his music video with an homage to French, Peck nods to an entire queer-country history.

So Peck isn’t really subverting the conventions of country music. He’s highlighting themes that have always been present in the culture, even if they were relegated to its margins. And, because Peck is a persona, he can embody those themes in their contradictory, rhizomic beauty. (Lil Nas X, by comparison, treats the genre and its history with less reverence than Peck does. Still, his success stands as a kind tribute not only to his gay and lesbian predecessors but also to older Black country stars, like DeFord Bailey and Charley Pride, and legendary Black cowboys, like Alberta’s John Ware.)

Because personas don’t have Wikipedia backstories, we don’t know much about Peck—only what we can infer. We notice, for instance, that he’s an outsider. We notice, too, that he cares for the people whose stories he tells. Everything from his mournful voice to his gentle affect seems to confirm this fact. And we notice that he’s unstuck in time. We see him, in the video for “No Glory in the West,” riding on horseback along the snowy mountain passes of the old frontier. Then we see him driving a ’70s Chevrolet in “Hexie Mountains” or touring with his band in a world of Fritos and iPhones in “Nothing Fades like the Light.”

He’s also a composite character, not a man without a face so much as a man with many faces. In his videos, he often appears as a presiding spirit or deity. In “Dead of Night,” shot at a Nevada brothel, needy men meet with women for melancholy, transactional sex. In “Queen of the Rodeo,” a drag queen competes in—and wins—a beauty pageant somewhere in Texas. In both clips, Peck appears as a spectral but empathetic presence. He haunts the hallways of the brothel and manifests, in the rodeo queen’s peripheral vision, as a mounted cowboy who rides alongside her while she hitchhikes to the event. Mostly, he’s a silent observer. Occasionally, though, he proffers a kind nod or places a consoling hand on a character’s knee.

So who is Orville Peck? He’s the embodiment of every misfit who ever populated the old frontier. He is the queer collective unconsciousness of the country music tradition. He knows about the longings that ranch hands and rodeo queens carry around with them. He knows that heartache and loneliness are existential conditions: cowboys, after all, have been singing about them for centuries. He knows, too, that the West is large and that there’s space for all kinds of people beneath its tall skies. “I recall somebody saying, ‘There ain’t no cowboys left,’” Peck sings on “Lafayette,” the most rollicking song on the new record. “But they ain’t met me and they ain’t met you.” We’re still here, he declares. We’ve been here all along.