This story was included in our November 2023 issue, devoted to some of the best writing The Walrus has published. You’ll find the rest of our selections here.

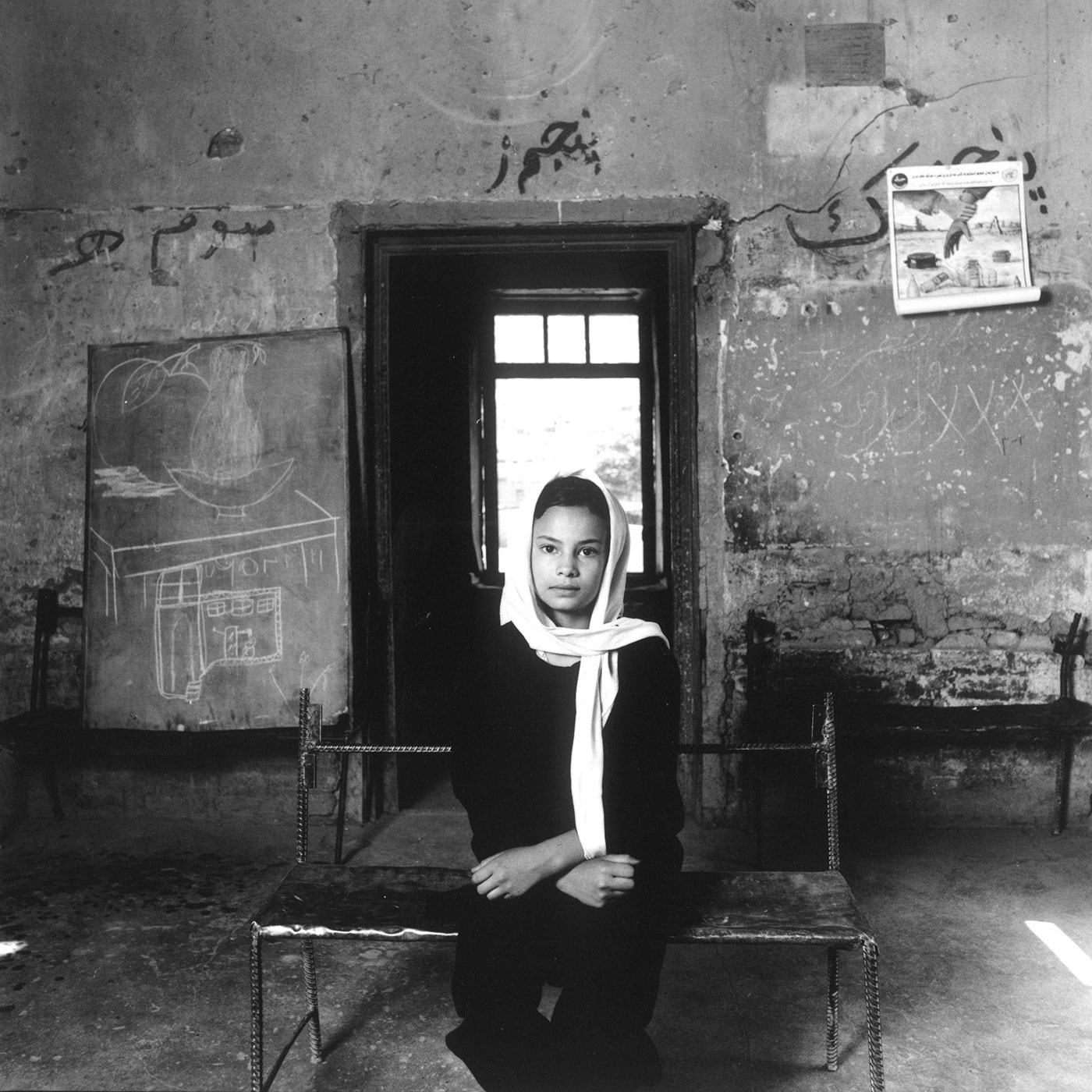

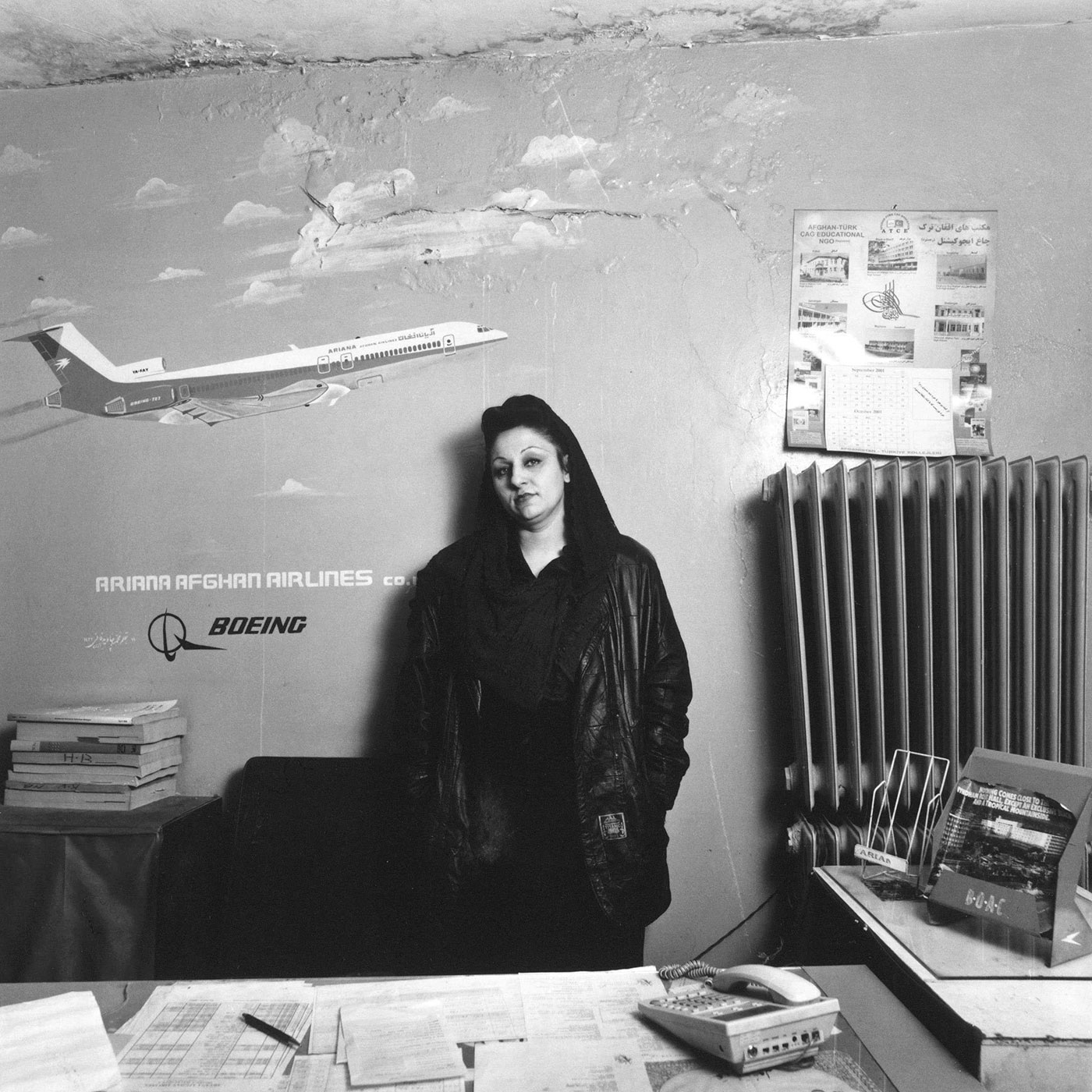

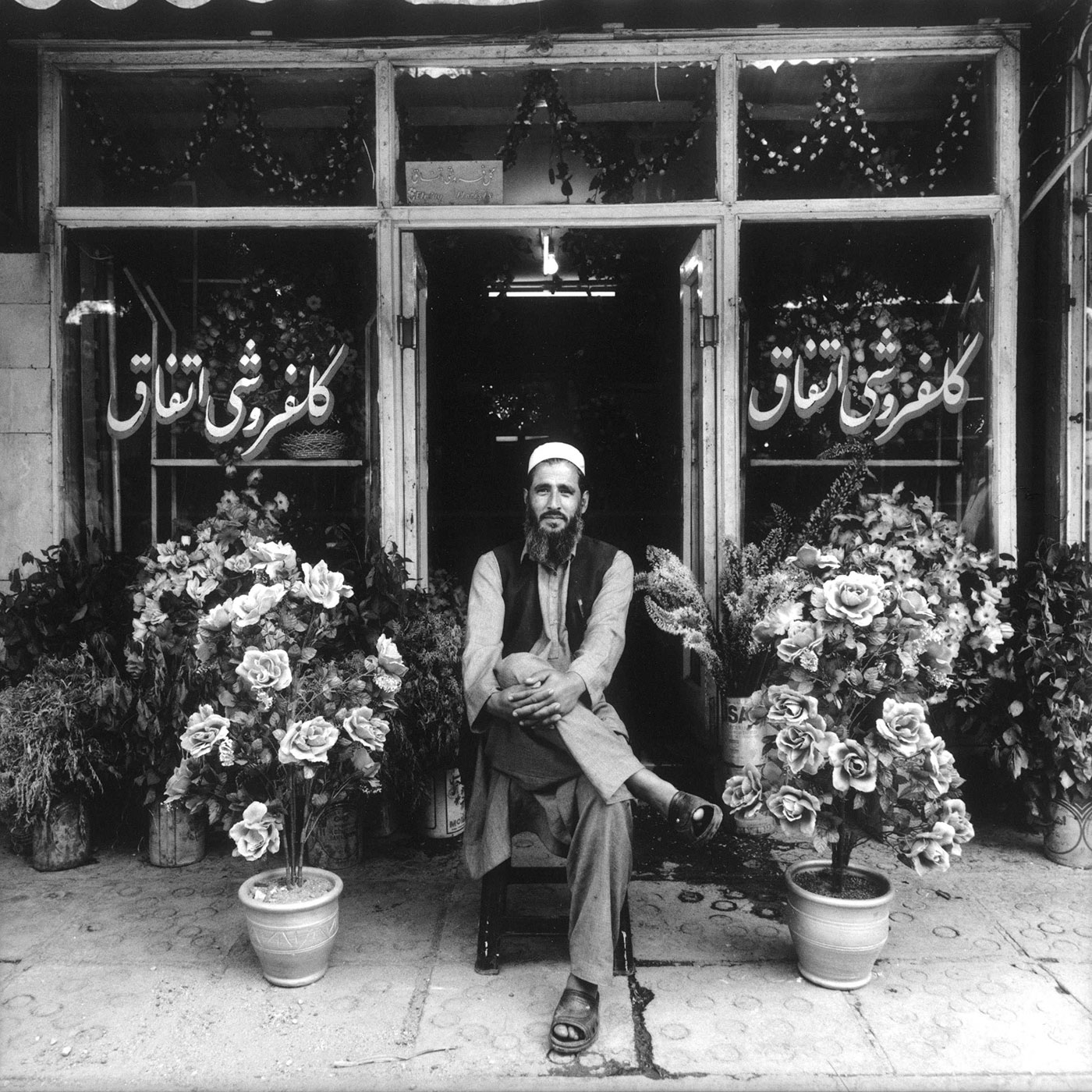

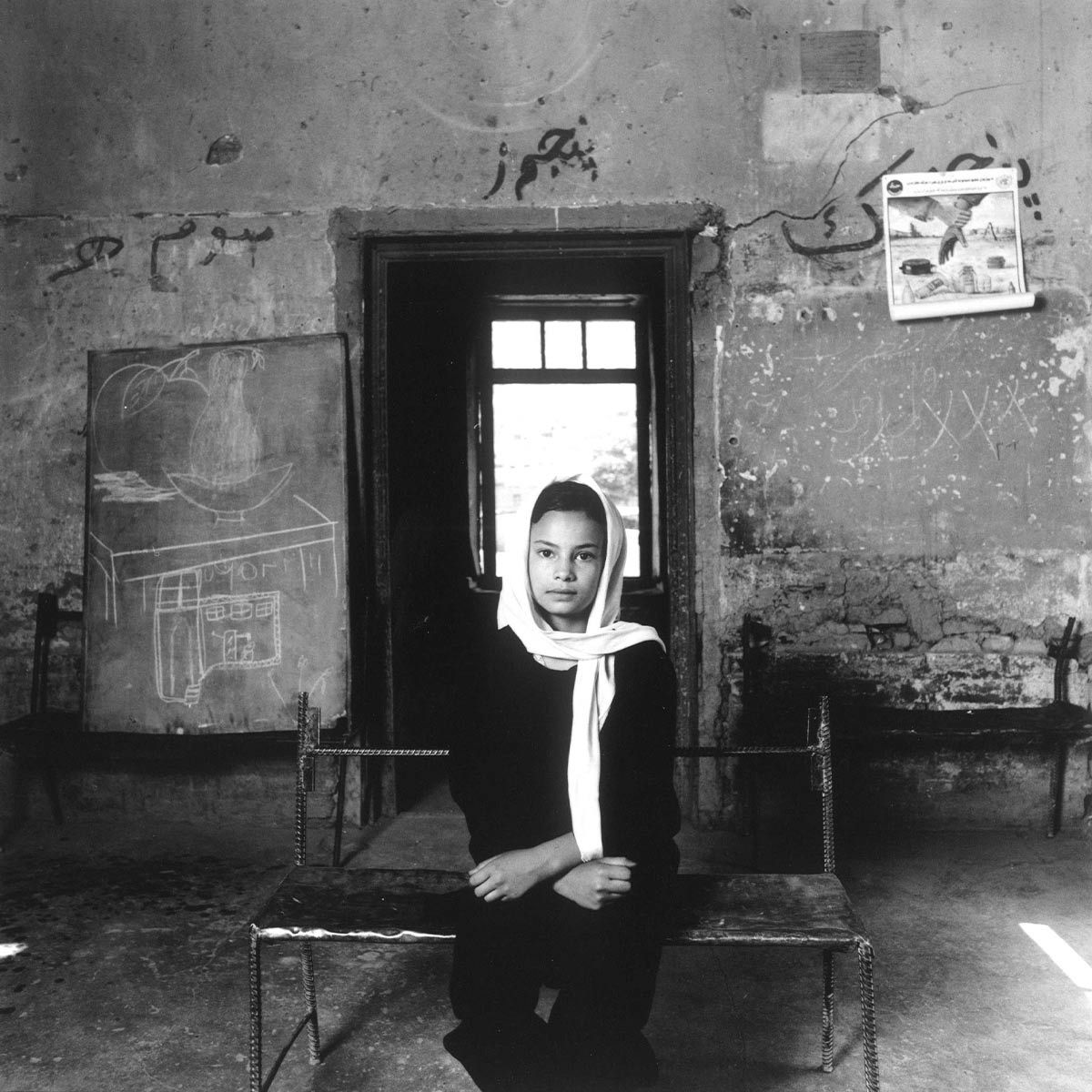

The background details in Ahmet Sel’s 2002 portrait series tell their own stories: a poster on a school wall warning children of potential mines, a flower shop in Kabul named Ittifaq—unity. One of the portrait subjects, Sabara Rahmani, is photographed among the ruins of the Afghan National Gallery, where she was the deputy director at the time. She still works there as a manager. Over the past two decades, she helped resurrect the gallery and even toured exhibits abroad. Since the Taliban returned to power in 2021, she and her colleagues have had to hide art that authorities might deem blasphemous, including work by women.

An artist herself, Rahmani has destroyed her own paintings to keep a low profile, but she tries to quietly support other women in the field. She’s seen the country’s potential in the past twenty years and hopes the world will try to help again. One day, she might even return to her art. “Why not?” she says. “Art is my love and art is my wish.”—Soraya Amiri, Journalists for Human Rights fellow, and Samia Madwar, senior editor, November 2023 issue

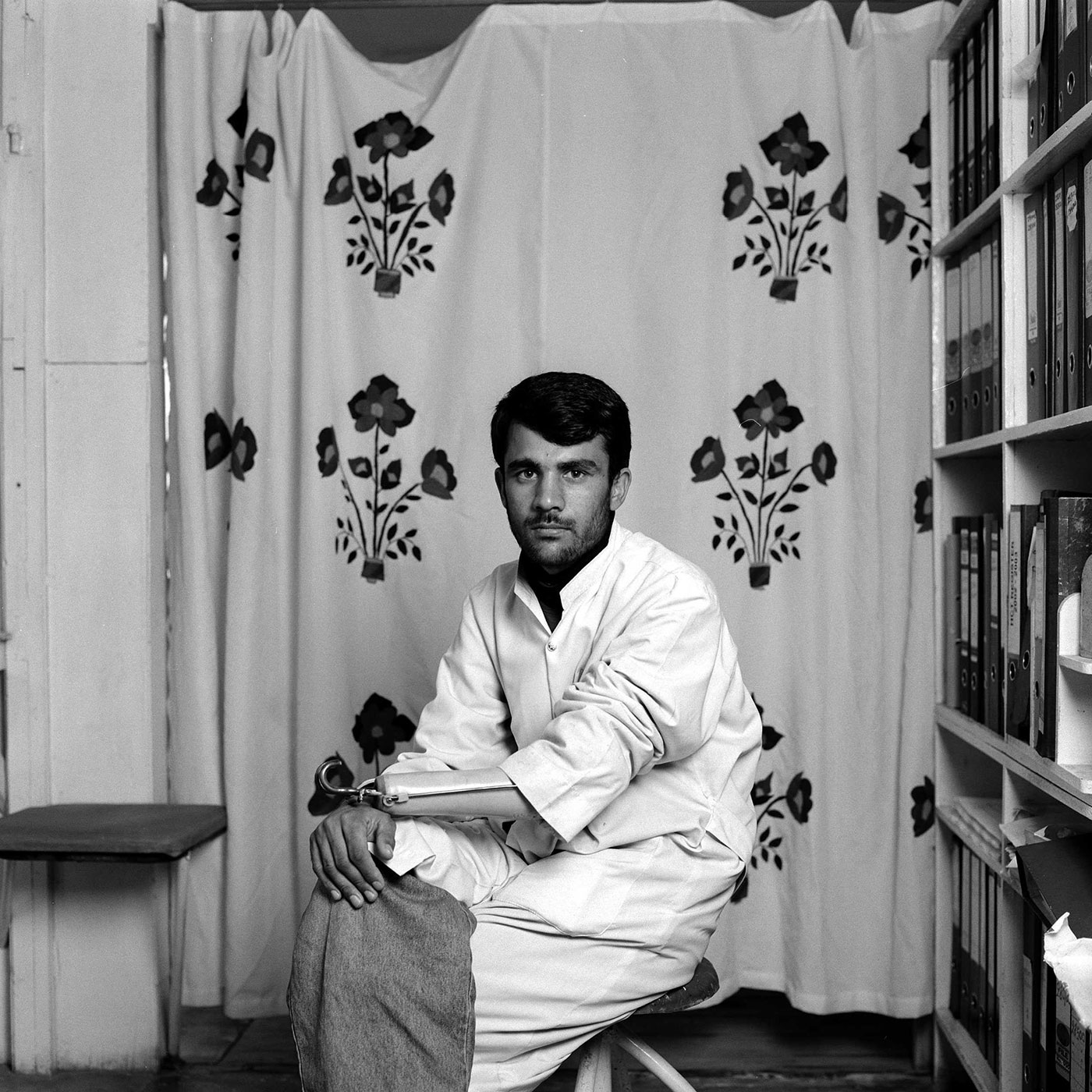

When the Taliban fell in Afghanistan in 2001, Turkish-born French photographer Ahmet Sel settled in Kabul for three months to shoot portraits. At first, he left his camera in his room because he didn’t want to be mistaken for a photojournalist. “People would have been afraid,” Sel said in an interview before this story was first published. Instead, he spent his days wandering the dusty streets and alleys of the war-ravaged capital, getting to know the city and allowing locals to get to know him. “To understand the light, the climate, and the people, I walked a great deal among the ruins of the city, down little lanes in the working-class quarters. I observed the bazaar merchants, I listened to the imam of the mosque speak of war, the war veterans evoke the memory of the resistance leader, Commandant Massoud. I became a fan of green tea, strongly recommended when it is hot, but also in winter when the snow falls on Kabul.”

Sel was frustrated by the generalized images of Afghans being exported by news media. He wanted to get into the guts and marrow of individual struggles, the spiritual architecture of post-war interior lives. How did people here perceive the future? How did they move beyond the emotional debris of deceased relatives, lost jobs, and bombed-out homes? Sel forged dozens of relationships that “ran deeper than photography.” He invited his new friends for a portrait session, and together they would select an environment that was personally significant: a garden or room or a familiar street. Sel provided minimal direction during the shoot, treating each portrait as a partnership. “Life can be normal,” he says, “and then in one moment, everything can change into a nightmare. I believe some of the people I photographed killed others in the war, and many had friends or family killed or were maimed. But we can permit optimism. These lives are larger than catastrophes.”