One fall afternoon, my friend Justice and I met up in a park near my apartment in East Vancouver for a songwriting session. We’d both been listening to Bon Iver’s album 22, A Million, a collection of songs with abstract, often distorted, lyrics and frequently without traditional verse/chorus structures. Here’s the verse, now the chorus, maybe a bridge—so much popular music of the last century has had these familiar signposts. On this album, it’s the layers of sonic textures—synthesizers, saxophones, affected vocals—that draw you in. Bon Iver is not alone in this; off the top of my head, I could name a number of chorusless songs by other influential artists, such as Father John Misty’s “I’m Writing a Novel,” or Sufjan Stevens’s “Death with Dignity.” My friend and I were so fired up about the conversation that day that I got to thinking, Is the chorus dead?

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more Walrus audio, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

On mainstream radio, for as long as I’ve been alive, the chorus has reigned supreme. My introduction to Western pop music was via a pocket-sized radio I had in the 1970s and 1980s that churned out three-and-half-minute songs with simple, catchy choruses I could learn in a single play. Later, when I started writing my own music, I adhered to the familiar formula. Choruses are radio-friendly—a sonic marker in an era where some listeners flip “every fifteen seconds,” according to an executive I talked to—so it makes sense that musicians would try to write for that format. If you’re a songwriter, you’ve probably heard the expression “don’t bore us, get to the chorus” (also the name of a 1995 greatest-hits collection by Roxette), and I agree that it’s an effective approach to songwriting.

Take one of the last century’s most instantly recognizable songs, “She Loves You” by the Beatles. It actually starts with its chorus (“She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah”). So do a host of other hits, leading right up to Drake’s Grammy-winning 2015 single “Hotline Bling.” While it’s more common to build to the payoff than to give it away off the top, the door-to-door journey from verse to chorus is pretty short in mainstream music. Scroll through the top-played pop songs on Spotify and you’ll find plenty of examples that mimic the verse/chorus format, and usually, the chorus comes before the one-minute mark. Ed Sheeran’s “Shape of You,” for instance, arguably has three chorus elements: the first comes in at twenty-nine seconds with the line, “Girl, you know I want your love,” the second soon after with “I’m in love with the shape of you,” and the third when he sings, “I’m in love with your body.” Clearly, you can’t have too much of a good thing when it comes to the year’s most popular song.

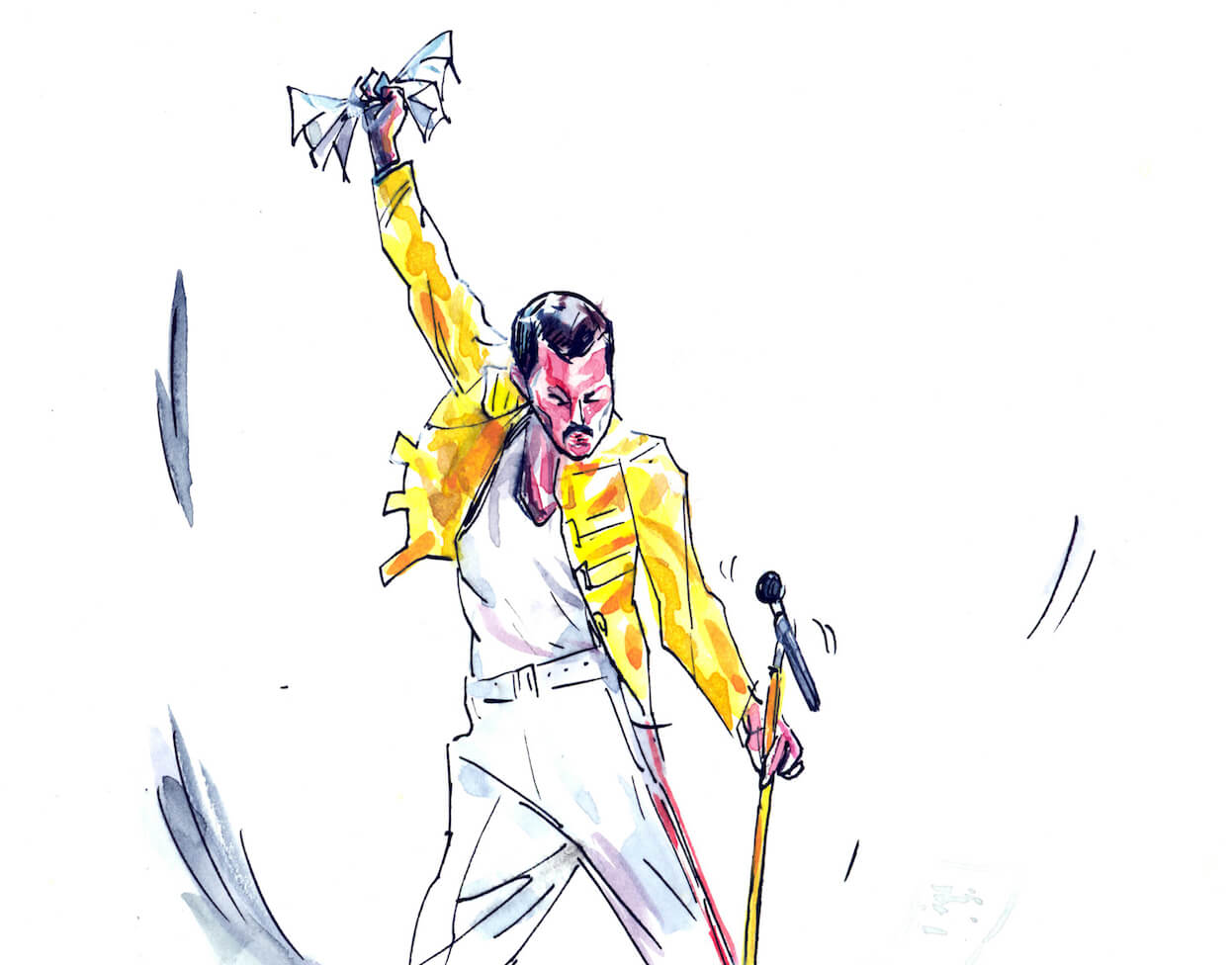

For all their importance, good choruses can be hard to write. I usually find that verse ideas come to me more easily, so it often takes a few weeks, and a lot of trial and error, to finish a song. Getting the chorus down means first asking yourself a number of important questions: Should the chorus be one word or a single line? Two lines or four? Should it be a question (Tina Turner: “What’s love got to do, got to do with it?”) or a statement (Katy Perry: “You’re gonna hear me roar”)? In the lyric-writing classes I teach in the University of British Columbia’s creative-writing program, I start students off by breaking down the components of a song. The chorus, I’ll suggest, is where you can express the main idea. At this point, I usually play them Queen’s “We Are the Champions” as an example of an anthemic chorus. It’s notable for the way the melody rises, the way Freddy Mercury lingers on the words as he sings, “We are the champions, my friends, and we’ll keep on fighting till the end.” Then there’s the repetition of the word champions four times in one chorus. You can’t help but sing along with him—and as you do, you’re declaring yourself to be a champion too.

But I also suggest that songs don’t have to have big choruses that occur in predictable spots. Delaying the chorus can be a compelling way to subvert listener expectations. The title track from Feist’s recent Pleasure holds off on revealing the first chorus until a minute and a half has passed. A way of delaying our pleasure, perhaps, of making it more delicious when the word is finally sung. Or you might skip the chorus altogether. Take Radiohead’s album A Moon Shaped Pool. The second single from this album is a six-and-a-half-minute song called “Daydreaming,” which, despite the use of lyrical repetition and a repetitive musical form verse to verse, contains no formal chorus that I can discern. It’s exactly the kind of less-predictable song fans have come to love and expect from Radiohead. You could argue that Radiohead enjoys a certain stylistic freedom because of its radio success in the nineties with “Creep,” a rather straightforward, guitar-driven rock song with conventional structure. Had it not been for “Creep,” perhaps Radiohead wouldn’t be as big a band today.

Or perhaps it would. Luckily for a lot of songwriters and recording artists, mainstream radio play isn’t the only way to build and maintain a fan base anymore. You might not achieve global success through DIY methods (in spite of the distant promise of YouTube fame), but it’s a way to make music outside traditional creative strictures. The use of home computers has changed how music is produced and shared, but it’s also changed the way songwriters think about composition. Now, instead of writing on an instrument, you can record bits of audio right into your computer and then start manipulating these bits, adding and subtracting instruments and effects, copying and pasting, and so on. Using a program, such as Ableton Live or Apple’s Logic Pro X, also means that production elements can be integrated into the song in real time so that you start to hear what your song is actually going to sound like on your laptop—you don’t have to wait to go into the studio to get the big picture. That is what the songs on 22, A Million sound like: as if they had been composed with an over-arching audio picture in mind from the start, rather than in someone’s kitchen or on a park bench, with an acoustic guitar.

With this approach, a songwriter can rely less on the lyrics to communicate the song’s message and can allow sound to do the work. That electronic drumbeat, those vocals resonating through reverb and delay effects, that weird little synth swirl—all that sonic intrigue can move the listener as much as a chorus can, so why not consider it part of the writing process? If you can create something sonically interesting, maybe there is less pressure to write a formulaic song.

Wes marskell of the Darcys finds himself guessing on a regular basis what the pop-music industry wants. “I think that writing a song with a big melody and a chorus is sort of less the intention of the songwriting machine,” he tells me. “They’re looking more for the uniqueness in the production, and I think that’s what becomes a big part of what they now consider a chorus.” In other words, a five-second hook or audio signature could be what sells a song. Remember that, back in 1998, Cher used an auto-tune effect to add sonic sizzle to her voice on her song “Believe”—it’s pretty hard now to have a discussion about that song without mentioning the way it was made.

Because of my own formal foundation in songwriting—nights in the basement with a guitar, woodshedding on Neil Young’s “Heart of Gold” and Cat Stevens’s “Wild World”—when a song bends form, I notice right away. I wonder if younger songwriters notice as much. Maybe they just think it’s normal. The fact that I’m noticing so many songs pushing the form now might also come from the fact that I’m seeking out this material as a way of informing my own craft. Or it may also be that, like everyone else, I have access to more music than ever before—via streaming sites, YouTube, and downloads. When someone tells me I should really hear a new album, I just add it to my playlist. What used to be called “alternative” is no longer as hard to discover; one can get musically educated pretty quickly with a monthly subscription to a streaming service.

When I asked James Sutton, music director at The Peak, a modern-rock station in Vancouver, what he thought about the new mainstreaming of chorusless songs, he brought up “Avant Gardener” by Australian songwriter Courtney Barnett as an example of one that’s done well on-air. The song is lyrically dense, it clocks in at over five minutes, and it has no real chorus, apart from a few pockets of repeated lines. Still, Sutton agrees that Barnett’s song is somewhat of an outlier. Most of the songs on mainstream radio remain more like Justin Bieber’s “Sorry.”

Personally, I love and respect that great combination of words and melody that will stop you in your tracks, hook you, and make you want to sing along. I can’t imagine a world without traditional verse/chorus songs, though my gut tells me that experimenting with form and structure is a powerful way to push the limits of pop. And as more songwriters try new approaches—whether because of advances in recording technology, curiosity, or just plain boredom—the more listeners will open up to new sounds and approaches. The best argument I can think of for busting up the traditional song structure is the effect it can have on music. It might not be that the chorus is dead so much as that it’s not the only way to make music that will succeed.

I’m happy to report that Justice and I left the park with a rough sketch of an idea. I have a recording of it on my phone, and I’ve listened to it a few times. It’s me singing a bunch of nonsense placeholder words over Justice’s guitar chords mixed with traffic sounds off Kingsway in the background. I haven’t shaped it into an actual song yet, but I think it has potential. Who knows, maybe one day I’ll get lucky and write one of those songs with a big catchy chorus that gets popular and rockets up the charts. Ask me how I feel about choruses then. I’ll be poolside and I just might have more to say.