A handcuffed middle-aged man with pale skin and fiery hair enters the prisoner box of Court 102 in Toronto’s Old City Hall, mumbling conspiracies. “I’m not crazy,” he says—but he’s clearly unwell. At times, he seems unsure of where he is. He’s here because he refused to comply with court orders after he allegedly assaulted a nurse—punched her and kicked her repeatedly, leaving her with a bloodied and swollen face and a lump on her head the size of an egg. Now he stands before Judge Beverly Brown, coordinator of the only full-time mental-health court in Canada, waiting to find out where he’ll sleep tonight.

The court hears from forensic psychiatrist Kiran Patel, who met with the accused earlier to assess his fitness to stand trial. The threshold is low, but in Patel’s opinion, the man doesn’t reach it. He suffers from schizophrenia and anti-social personality disorder, and he hasn’t been taking his medication. Asked whether he understood the charges against him, the accused responded in non sequiturs: “You gave me AIDS,” he said. “Are you sweating me?” Asked whether he understood the choice of pleas available to him, he swore at the doctor. The hearing lasts about thirty minutes, punctuated by several interruptions from the accused—the kind that could see him charged with contempt in a regular court. Eventually, Brown decides the man will start a sixty-day treatment program tomorrow. Tonight, he’ll have to go back to jail.

Founded in 1998, Court 102 has been a bright spot in the dark history of mental-health treatment in this country. Starting in the 1950s, the increasing use of Valium, lithium, chlorpromazine, and other drugs allowed asylums to divest themselves of a growing number of patients. Many who were discharged found themselves unable to cope with the world into which they had been released. Government cuts to health care and social programs made things worse. Today, the mentally ill are one of the most criminalized populations in the country: by some estimates, nearly 35 percent of federal inmates suffer from psychological disorders.

Court 102 helps the mentally ill by ensuring that offenders spend less time in pretrial custody and more time getting well, be it well enough to stand trial or well enough to re-enter society. It’s a catch in the drain that keeps this vulnerable population from recirculating through a system not designed to support them. Yet beyond the legal and mental-health communities, almost nobody knows that Court 102 even exists.

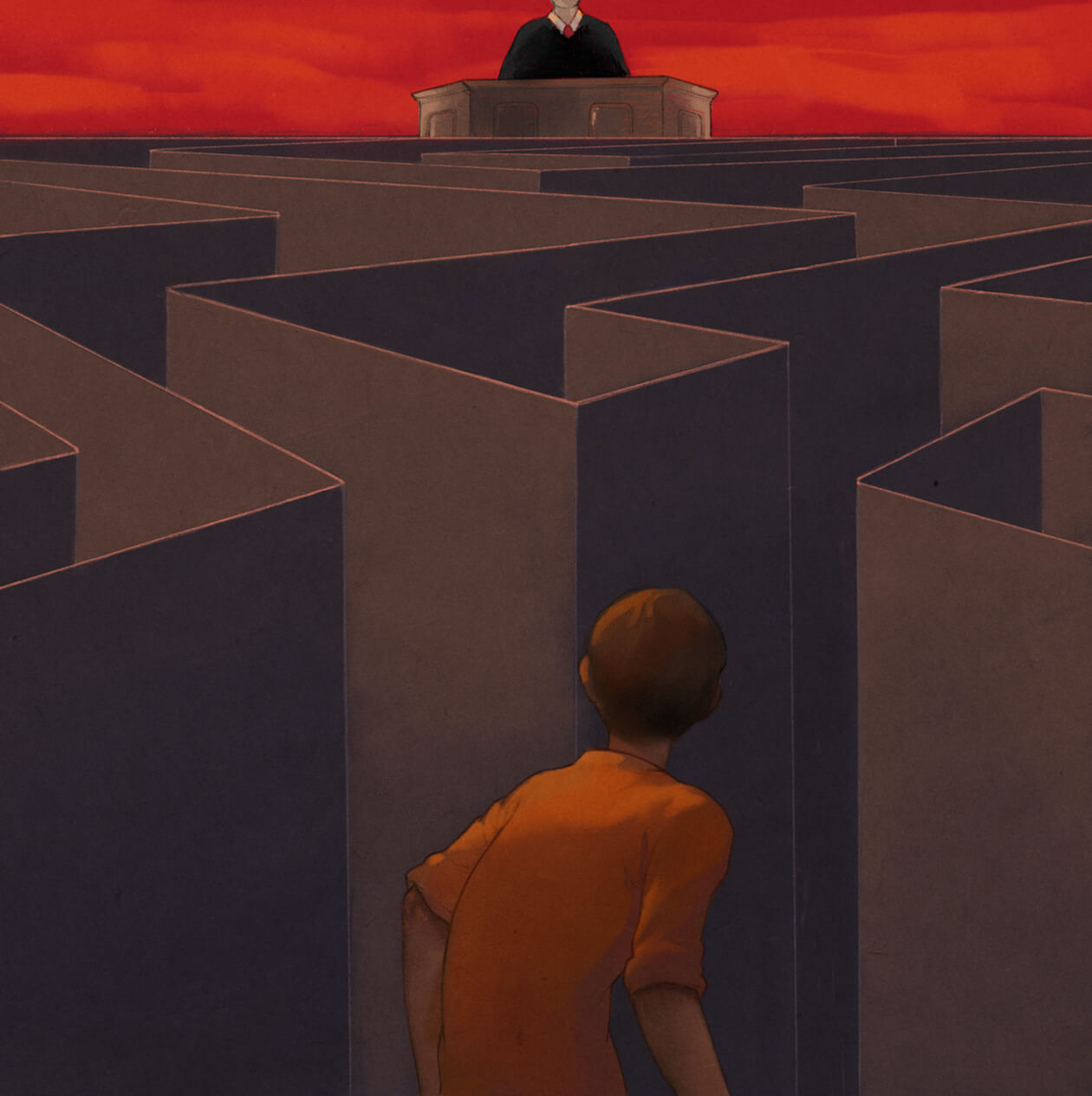

For mentally ill offenders, the criminal-justice system is a grim place. Everywhere an accused turns, says Natasha Bartlett of Fred Victor, a charity that serves homeless and low-income Toronto residents, “there are biases and judgments and barriers”: judges and lawyers lack mental-health training; prisons lack adequate treatment programs. It’s a system that ostensibly supports rehabilitation, but is structured to punish, and it’s one that Bartlett says criminalizes mental illness. “It’s no longer the 1950s where we can force some cookie-cutter kind of justice on everyone,” she says. “Why can’t we see the court as something that helps people make a change so they can come back to society?”

In Court 102, the first objective is to make sure pretrial issues of fitness are dealt with quickly. One-on-one assessments with a forensic psychiatrist are conducted in the next room, and orders for treatment are usually handed down the same day. Those charged with non-violent or relatively minor offences can volunteer to enter an intensive support program without having to plead guilty. They’re set up with a community worker, a psychiatrist, and shelter—and their criminal record will be unaffected.

The culture of the court has been adapted to accommodate the people it serves. One trio of accused includes a woman in a baseball cap and a Toronto Raptors hoodie, a man who intermittently paces back and forth, and another who cracks open a Sprite during his testimony. “We just look the other way,” Brown says. “We’re more understanding of people’s individual situations.” Many have severe anxiety issues, she explains, and if wearing sunglasses or carrying a trinket makes them feel more at ease, then taking those things away would be a greater blow to justice than permitting them would be to decorum.

The approach does have its critics—among them a few legal theorists and many conservative pundits—whose objections run along familiar lines: mental-health courts are another means of mollycoddling offenders; they don’t respect the victims of crime; they give hardened criminals a softer landing. “And to those critics, I’d say, ‘Have you lived with schizophrenia for twenty years without support?’” Bartlett says. Serious mental illness can feel like a life sentence in itself. And treatment is not soft time. Patients must check in regularly with their social workers, psychiatrists, and the court. The program can be stressful and invasive, Bartlett adds. “They have to be willing to change the behaviours of a lifetime.”

In the traditional court system, mentally ill offenders typically are released without financial assistance, without social supports, without anywhere to turn. Say a psychotic defendant does a week-long stint for some petty crime, having already been held in custody far longer, and then is turned back out onto the street. “What do you think is going to happen again?” Brown asks. “How creative is that? Here, we’re trying to get them the supports they need so they don’t fall into that pattern and don’t keep committing crimes—so the outcome for the community is better in the long run.”

For most offenders, however, the old way is the only one available. Funding for mental-health courts remains scarce—perhaps because there’s still a lack of published research to justify their existence. However, a 2007 article in the Journal of American Psychiatry shows a 26 percent drop in recidivism among those who’ve graduated from similar programs in the United States, where the courts are kept afloat through federal grants. And York University will be releasing a report on Court 102 this fall. The hope is that similar findings in Canada will encourage politicians to fight for increased funding. “If you want to sell something, you’ve got to prove that it works,” Bartlett says. “Some politician needs to get hold of this like a pit bull and not let go.”

Brown has all the proof she needs. Throughout treatment, offenders show up to court regularly to see her—their stories don’t end after one court appearance. She sees men with psychosis find work, women with schizophrenia find shelter. She’s even seen a young woman go on to study social work and return to the courtroom on a field trip with her classmates. And each time someone graduates, the judge tells them they’re always welcome to pop in: “You can come back if you’re under stress, or you can come back just to visit us.” First they laugh at her, Brown says. Then they come back to say hello.

This appeared in the November 2016 issue.