Summers are as much defined by songs as they are sweat; however this past season’s hits were considerably less predictable than its heat.

One of the most critically acclaimed albums came courtesy of Carly Rae Jepsen, whose Emotion is being rightly hailed, even by bastions of indie culture, for its collection of “perfect pop songs.”

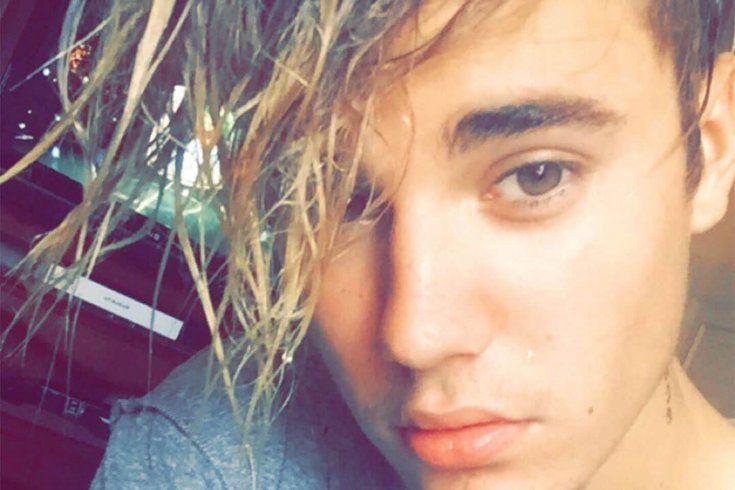

In 2012, Jepsen’s pal Justin Bieber helped her blow up the first time, after hearing her “Call Me Maybe”—an inescapable viral hit that went on to hold Billboard’s number-one position for nine weeks. Still ubiquitous worldwide, it seemed destined to trap Jepsen as one-hit wonder trivia question before Emotion remade her into a critical darling.

Bieber is no stranger to chart-topping hits. Despite his many sales accomplishments, until recently he’d never enjoyed much love from music critics or non-tweenage fans. Note the past tense. Five years after his excruciating, repetitive “Baby,” he somehow landed song-of-the-summer contender “Where Are Ü Now,” an unexpected collaboration with electronic dance music (EDM) producers Skrillex and Diplo. (The latter’s Major Lazer also delivered, with DJ Snake, the best and weirdest summer smash, “Lean On,” which currently boasts over 500 million YouTube plays.)

In late August, Biebs upped the ante with a Skrillex-produced sequel, “What Do You Mean,” that not only debuted at number one within hours but also prompted Noisey, the music wing of Vice’s hipster empire, to declare “sorry we’re not sorry, it rules” and “We have high hopes for the album.”

All this just three years out from Bieber being booed at the Grey Cup (for the audacity of performing in front of a crowd old enough to drive), and one year out from being booed in absentia at the Junos (for the audacity of winning an award).

The Weeknd, on the other hand, is no stranger to acclaim. Beginning in 2011, the Canadian singer (born Abel Tesfaye) released a series of mixtapes recounting his hedonistic Toronto adventures. The debauched lyrics and murky beats helped define alternative R&B and proved that he didn’t need the mainstream to be a success. That was then. Now he is the latest Canadian to reach the top of Billboard’s charts: The Weeknd’s “Can’t Feel My Face” is a collaboration with Max Martin, a Swedish songwriter/producer who first achieved the feat sixteen years ago with Britney Spears’s “. . . Baby One More Time.”

Tesfaye, the once-underground hero, has gone from singing creepily about a sexual conquest needing to be “High For This” to making music that my five-year-old sings himself to sleep with. (“I can’t feel my face when I’m with Pikachu.”) Again, the result is as beloved by critics and cool kids as it is by the general consumer.

What’s happened is that pop has become the new alternative.

Back in the 1980s, pop music was taken seriously thanks to the likes of Prince, Madonna, George Michael, and Michael and Janet Jackson. Sure, there were one-hit wonders and atrocious acts (every era has those), but “pop star” was a compliment even for “real” artists. That changed in the 1990s as the alt-revolution caught fire amidst pop’s precipitous decline in quality. With the pop cultural pendulum swinging back toward anti-corporate authenticity, music’s most corporate genre reacted by becoming increasingly conservative. Even the era’s best pop act, the Spice Girls, were assembled and sold as living dolls (and sold as real dolls, too).

Acts like Jane’s Addiction, Nirvana, Nine Inch Nails, and Breeders sold millions and fuelled the rise of alt-radio and alt-festivals like Lollapalooza. But they were literally the alternative to pop, which at the time was repped by Disney themes, Michael Bolton’s blue-eyed soul covers, and Natalie Cole’s duets with her dead dad. Exceptional exceptions like Deee-Lite’s “Groove Is in the Heart” emphasized how far pop had fallen from its effervescent and experimental ’80s heyday.

By the end of the decade, hip hop had grown into its own distinct self-sustaining industry while the rave scene pushed a few electronic acts like Chemical Brothers, Daft Punk, and Fatboy Slim slightly above ground. Pop, meanwhile, targeted the teen market, with the still-mighty mainstream music industry giving Backstreet Boys, ’NSync, and Spears heavy pushes.

Ironically, our current golden age of pop can be traced to this much-maligned cultural moment—because the mastermind of the ’90s teen-pop explosion was the aforementioned Max Martin.

His Weeknd smash was actually his twenty-first number one song, catapulting him past The Beatles’ twenty, and his fifty-eighth top ten hit. But to put Martin’s pop cultural omnipresence into proper relief, in the last sixteen months alone, he also wrote Katy Perry’s “Dark Horse,” Arianna Grande’s “Problem,” and Taylor Swift’s “Shake It Off,” “Blank Space,” and “Bad Blood.”

Music genres have always cycled through peaks of cultural prominence. Pop is an anomaly, though, because even though it is by definition popular, it’s rarely been respected. But as Vice’s electronic site Thump points out, “we now very much exist in a culture that is prepared to intellectually value pop music more than ever before.”

A few things have happened between the low point of the ’90s and now to make this transition possible.

First, the rise of the critical theory of “poptimism”—a rejection of the so-called rockist tendency to place more value in music that comes from a rock or folk tradition of singer-songwriters and instrumentalists—provided pop with cultural credibility. This led to media coverage in hipster publications like Pitchfork, Vice, and Fader. Their blessings helped broaden pop’s audience to people who may previously have been too snobby to even consider it.

As well, what used to be one of alternative and indie music’s big selling points—that they were made free from corporate influence—ceased to matter. Hip hop’s aspirational attitude made it okay, even cool, to actively seek popular success—just as the collapse of record sales made self-promotion more necessary. Then there is pop music’s cultural diversity compared to, as Pitchfork put it, “the unbearable whiteness of indie.”

But arguably the biggest shift has come courtesy of Martin and his former protégés.

Britney Spears, our prototypical pop princess, may have gone down as a pre-millennial trivia question, but for 2001’s “I’m a Slave 4 U,” an experimental mega-hit that smoothed producer Pharrell Williams’ transition from hip hop to pop, and 2003’s similarly daring “Toxic,” produced by Sweden’s Bloodshy & Avant.

During her infamous 2007 meltdown, Spears dropped Blackout, a record defined by its underground club beats. Radio gave it a chance because of her pop pedigree, unintentionally opening the mainstream’s doors to what would become known as EDM.

Former ’NSync star (and Spears ex-boyfriend) Justin Timberlake also helped change the perception of pop with the one-two punch of his albums Justified (2002) and FutureSex/Love Sounds (2006).

But perhaps the most influential modern pop artist is Robyn, the Swedish singer who had a minor hit in the late ’90s with the Martin-penned “Show Me Love.” She re-emerged in the mid-2000s as an independent artist who made electro-pop rather than indie rock. The soaring cinematics of 2007’s “With Every Heartbeat” laid the groundwork for her Body Talk trilogy, which ushered in the 2010s with perfect epics like “Call Your Girlfriend” and “Dancing on My Own.” Suddenly pop was legitimately great.

Martin was also improving at his job. Beginning with Kelly Clarkson’s rock-fuelled 2004 smash “Since U Been Gone,” he pumped out successive chart-toppers for Pink, Ke$ha, Katy Perry, Usher, Bieber, Taylor, and Spears, whose “Til the World Ends” provided another genre highlight. Near the same time, Rihanna and Nicki Minaj started hooking up with EDM producers like Calvin Harris and David Guetta, just as Bieber would later find success with Skrillex.

Other pop stars are taking different routes. Miley Cyrus’s Disney breakup album Bangerz (2013) was executive produced by Atlanta trap hero Mike Will Made-It, while her just-released (and admittedly critically panned) surprise album Miley Cyrus & The Dead Petz is a collaboration with alt-era survivors Flaming Lips. Bruno Mars achieved his greatest hit, “Uptown Funk,” by teaming up with Amy Winehouse producer Mark Ronson.

Jepsen, meanwhile, has mined the indie underground for songwriting and production assists from Blood Orange’s Dev Hynes, Vampire Weekend’s Rostam Batmanglig, Haim producer Ariel Rechtshaid, The Zolas’s Zachary Gray, and one of Martin’s many protégés, Shellback.

What defines this current musical moment is cross-pollination, experimentation, and quality, all forced upon a free-falling industry that’s had no choice but try something different to make ends meet. The rise of online streaming, and ever-increasing importance of live ticket sales, has given fans far more influence over what becomes popular—and therefore pop—than radio’s top-down playlists ever did. (And let’s not forget that both Drake and Bieber began as YouTube phenoms, or that the video site sent Psy’s regional K-pop global, to the tune of about 4 billion(!) views.)

The result is a world where mainstream music is weirder and underground music is catchier, and the difference between them fades by the day. Perhaps pop’s new golden age, like alternative, will eventually eat itself. But in the meantime, all we can do is follow Taylor Swift’s lead and party like it’s 1989.