After forty-two years of dictatorship and crippling Western economic and trade sanctions, change may finally be afoot for the people of Burma, one of the world’s most downtrodden citizenries. Last spring, a series of meetings was held between the ruling military junta and more than a thousand invited delegates. The purpose of the National Convention was to hammer out a constitution and usher in democratic reforms. While the gathering took place, on and off, from May 17 to July 9,there was considerable rancour and it produced little in the way of concrete results. Nonetheless, the governing generals promised the National Convention would continue at a second meeting,to be held sometime “after the rainy season,” perhaps in November.

If the next stage of the conference does take place, and if any meaningful measure of democracy is restored, the world’s governments and corporations may finally drop their debilitating sanctions and help bring Burma—or Myanmar as its military rulers have been calling it since 1989—into the international community. This is the general hope of the delegates to the National Convention and even of those who boycotted that first meeting, including the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy (snld) and, more critically, the National League for Democracy (nld), which won the general elections of 1990 only to be denied power, and whose leader, Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, is still under house arrest.

Meanwhile, life in Burma remains precarious for most of its impoverished citizens. I met Rosie in the city of Mandalay at her Grace Café teahouse, where she employs thirty boys, aged thirteen to fifteen. She had worked as a nurse for years while her husband repaired old cars and resold them, before buying the teahouse with a loan from her grandmother. Teahouses are a Burmese tradition, a social institution where friendly gatherings and business deals can be conducted inexpensively.

“I believe God is love,” said Rosie as boys on her staff darted among the low teak tables that sprinkled onto the sidewalk. Born in the hill station of Taunggyi, northeast of the capital Rangoon (called Yangon by the government), Rosie is Shan, one of eight main ethnic groups in Burma, and one that was partially Christianized during more than a century of British rule, which ended in 1948. A sign on the rear wall of Rosie’s shop cites 1 Corinthians 13:4—“Love is patient, kind, without envy.”

Like any business, running a tea house has its risks, but for her employees the business of survival is even riskier. Her boys, she said, wander in from the streets or are brought by relatives, strangers, or occasionally by authorities. According to unicef, fewer than half of Burma’s children continue their education after grade four, so these boys have nowhere else to go. And yet, as I watched them speed between the tables, they chattered and laughed without reservation.

Contrary as it may sound, Burmese citizens seem to project an old-fashioned, almost uncool embrace of welcome. Maybe they’re obeying the government’s dictum to banish all “negative views.” Emblazoned upon public byways and national centres are the four commandments of the ruling military junta:

“People’s Desire—Oppose those relying on external elements, acting as stooges, holding negative views; Oppose those trying to jeopardize stability of the State and progress of the nation; Oppose foreign nationals interfering in internal affairs of the state; Crush all internal and external destructive elements as the common enemy.”

Also in Mandalay is Mahamuni Paya, the city’s most venerated pagoda, where the devoted fold to their knees on cool tiles decorated with lotus blossoms. Watching the devotees in mid-afternoon as they prostrate and meditate, I wondered: Is it devotion or unemployment that brings them to this serene and golden site?

The focus of all the fervour was a bronze statue, four metres high, of the Rakhine Buddha, said to have been cast about two thousand years ago. Its veneer has vanished, replaced by gold leaves that countless male worshippers have applied with their thumbs. Delicate as butterfly wings, the tiny wafers of gold come in small stacks, like miniature packs of cards, each glistening leaf separated by a smooth square of hammered bamboo paper.

Some of the gold leaves come from Gold Rose, a factory on 36th Street where I was later taken by my guide. A pedal-rickshaw driver, his mouth a scarlet slash of betel nut amid a complexion white with thanaka, a sandalwood unguent used as a sunscreen, he pulled up alongside an inconspicuous emporium touting a medley of brocaded puppets with gilt complexions, lacquerware and, of course, gold leaf. Shaded by a tin awning and woven rattan walls, four bare-chested men without a gram of body fat among them used heavy mallets to pound out the gold leaves.

The rickshaw driver led me out back. We strode through a sooty kitchen to a concrete staircase and down to a small, windowless basement where eight young women sat in opposing rows. Each brandishing two rounded wooden clubs, they were cudgelling small sheets of bamboo into impossibly thin, opaque squares to be slipped between the gold leaves that were being battered into existence upstairs. Their workplace was a reverberating inferno.

“Ears break,” murmured the rickshaw man as we climbed back above ground. But the workers exhibited a Zen-like patience as they focused on their single, repeated task. Under the totalitarian regime, there is no protection for them. The dominant religion—Rosie and the Shan people’s Christianity notwithstanding—is Buddhism and it is, perhaps, their main source of comfort.

The governing generals, loath to relinquish their power, are openly critical of the dangers of democracy. “The Western nations’ theory of democracy first, democracy second, and democracy third has not only failed in many developing countries but has created instability and chaos,” states a Myanmar government publication. “It is regretful that the development of the people of Myanmar is being hampered by the same nations expressing their desire to bestow Myanmar people with human rights, but who are in reality depriving the Myanmar people of their rights to development and prosperity.”

The imposition of increasingly punitive sanctions by many Western nations since 1991 has isolated Burma’s 42.5 million people from the rest of the world and prevented the country’s economy from keeping pace with its neighbours. True, Burma’s teak forests continue to be stripped for export to China and Thailand’s furniture factories. Burmese rubies and jade manage to slip through the barricade and onto Western fingers and throats. And there is always the heroin trade. But the bumpy two-lane highway between Rangoon and Mandalay is sparsely populated with trucks. Only a few barges travel the Irrawaddy River between the nation’s two major cities, and most of those are carrying old-growth teak trunks.

(As George Orwell, who served from 1922 to 1927 with the Indian Imperial Police in Burma, lamented in his first novel Burmese Days: “All the forests shaved flat—chewed into wood pulp for the News of the World or sawn into gramophone cases.” Interestingly, Burmese Days is widely available, an approved text in this censored land, much as Graham Greene’s The Quiet American is ubiquitous in Vietnam. Both books flay the imperial conquerors and paint the oppressed societies in sympathetic brushstrokes.)

In the marketplaces, lacquerware peddlers and jewel merchants display their beautiful fripperies, but few Western tourists buy anything. Since Burma is virtually disconnected from the world banking system, visitors usually bring just enough cash to live on. The few atm machines that exist are idle. Traveller’s cheques and credit cards are rarely accepted. And any tourist who carries a wad of cash becomes a target for robbers.

At a governmental level, Burma is the author of its own misfortune. In 1962, just fourteen years after Burma won independence from Britain, General Ne Win seized power and, for the most part, closed the country to the outside world. The cadre of younger generals who replaced the aging Ne Win, popularly called the “Puppet Master,” in 1988 were only marginally less dictatorial. However, the current leader, General Khin Nyunt, initiated a breakthrough of sorts by promising, in 2000, to pursue a seven-step road map to democracy.

The promise was made just two days after new U.S. sanctions — including a ban on all imports from Burma—came into effect. But it was not until May of this year—shortly after Razali Ismail, the United Nations’ special envoy to Burma, held talks with Nyunt and nld leader Suu Kyi—that the first step towards democracy and national reconciliation was taken.

On May 17, the convention opened at a military complex (and behind checkpoints designed to keep out the uninvited), in the town of Nyaung Hnapin, forty kilometres north of Rangoon. Although the snld and Suu Kyi’s nld were missing, a reported 1,076 delegates, including representatives from seven of the ten political parties recognized by the government, did attend.

The chairman of the assembly, Lieutenant General Thein Sein, promised a “disciplined, flourishing democracy desired by the people,” though no timetable was on offer. A code of conduct cautioned representatives against storming out of meetings or making derogatory comments. To ensure that everyone stuck with the plan, the government issued a document that featured “104 principles” to be followed by the delegates. These “principles” amounted to the junta’s agenda, and made this first step appear uncomfortably close to a goose step. Thirteen groups promptly unveiled their own agendas, proposing stronger autonomy for state assemblies and the decentralization of powers—including the right to raise local armies.

While these alternative agendas were ignored, the talks nonetheless continued until July 9. Then, everyone went home. The National Convention, declared the government, was a success. “They told us to meet again in the dry season,” Sao Khai Hpa, chairman of the Shan State Army, told The Irrawaddy, an English-language publication put out by Burmese exiles in Thailand. But the generals will not be hurried, and some theorize they will not have to introduce reforms until 2006, when Burma assumes the presidency of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (asean). Meanwhile, according to Amnesty International, 1,350 political detainees remain in jail.

The real credibility issue overhanging the National Convention concerns Suu Kyi. Media-wise and charismatic, the Nobel laureate is the political equivalent in Burma of the Dalai Lama. She has been uncompromising, perhaps unrealistically so, in her demands that the usurping generals return the country to its people. Beyond Burma’s borders, she is a heroine, the international symbol for her country’s suffering, and her house arrest the main justification for the sanctions. But within Burma, there are murmurs of dissatisfaction over Suu Kyi’s all-or-nothing stand. Meanwhile, a report by the International Crisis Group explicitly disagrees with hardline factions in Burma and calls for a balance between “what is desirable and what is achievable.”

Between 1993 and 1996, the US imposed over sixty sets of unilateral sanctions against thirty-five nations, even though sanctions are now widely thought to be a “blunt instrument” that hurt the oppressed instead of punishing the oppressors. A 1999 report titled “Feeling Good Or Doing Good With Sanctions” by the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies, looked at five sanctioned countries, including Burma, and noted that such measures allow dictatorial administrations “to blame internal economic problems on the sanctions and to appeal to anti-American nationalism.” What would be far more effective, said the report, would be “proactive, flexible engagement.”

Though Canada is far from adopting such a policy, Bill Graham, as foreign affairs minister in 2003, conceded that the use of strict sanctions “hits the poorest people in the country who produce these products. It’s not going to hit the leaders.” While Ottawa has not imposed unilateral sanctions on Burma, it has taken restrictive measures. “Canadian policy does not encourage trade with, or investment in, Burma, nor do we engage in Ministerial-level visits to Burma,” reads the Department of Foreign Affairs Web page on Burma. “This is in keeping with the stated wishes of Burma’s democracy leader and Nobel Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi.” Consistent with government policy, Canadian companies, such as the Bank of Nova Scotia, Petro-Canada, and Seagrams, turned away from investment opportunities in Burma during the 1990s.

The US has not appointed an ambassador to Burma since 1990. Washington banned all investment in the country in 1997, and last year barred imports of anything mined, made, grown, or assembled there. It also froze any US-based assets belonging to Burma or its leaders and opposed any loan assistance from the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund.

The list of chastizing governments and organizations is a long one. The European Union has been stepping up measures to discourage trade with Burma since 1996. In June 2000, the International Labor Organization censured Burma over its use of forced labour. In June 2003, Japan stopped all aid to Burma after years as its biggest donor. And a month later even Malaysia, which has never ceased trading with Burma, suggested that asean expel Burma over the slow pace of its democratic reforms and its human rights violations.

At a grassroots level, activist pressure has succeeded in limiting commercial trade with Burma. For example, two years ago Amnesty International targeted stores in Switzerland, France, and Holland that carried shirts and lingerie made at a factory in Rangoon. Suppliers subsequently moved production to Cambodia, China, and Madagascar—putting three thousand workers, mainly female, out of work.

Companies such as Anheuser-Busch,Pepsi-Cola, Best Western, Carlsberg, Compaq, Levi Strauss & Co., J.Crew, Motorola, and Philips, among many others, all pulled out during the 1990s, in response to boycotts, government restrictions, or a combination of both.

So how does this marooned nation operate? Well, there’s the drug money and then there is China. With scant criticism from Western powers reluctant to offend the emerging economic giant, China has invested heavily, beginning with a $250-million (US) loan in 1998 for a 280-megawatt power plant near Pyinmana. Its commercial trade with Burma in 1999 jumped 124 percent and has increased significantly since. There have been billion-dollar military deliveries from China, the first shipment of which arrived in 1991, and included eleven F-7 jets. (The defeat of rebels from various regional ethnic groups is largely due to this Chinese arsenal.) Other countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and India have also been busily trading with the sanctioned nation.

Relying on cracks in the sanctions wall, however, is a short-term solution at best. No doubt, the absence of freedom and the passivity borne of low expectations can subdue, even tranquillize, a population. But with power running uncertainly and the economy stagnant,Burma could descend into chaos. Hope resides in the National Convention and, perhaps, in countries such as Canada reviewing their “principled” stance vis-à-vis this, one of Asia’s most abject peoples.

The boys I saw in Rosie’s teahouse looked well taken care of. Their shirts and shorts were clean. And besides feeding and clothing them, Rosie provided two large showers behind the kitchen. At night, she gave them blankets for sleeping on the teahouse floor. After six months or a year, they leave voluntarily, she said, taking the salary they have earned (a pittance) and what basic life skills the teahouse has given them—cleanliness, deportment, skills in sweeping, washing, cooking, and serving the public.

“Do you cry when one leaves?” I asked Rosie.

“No,” she replied.

“Do they love you?”

“I think so,” she said.

Rosie’s boys are the lucky ones, at least for a time, as they settle into this boarding school-cum-orphanage before facing the uncertain future of their unordered Burmese days.

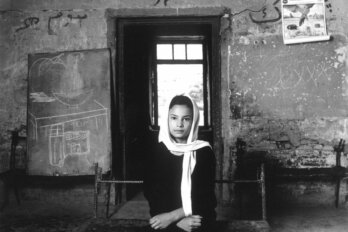

About the Portraits

Born in Kalemyo, Burma, in 1966, freelance photographer Chan Chao left his country at the age of twelve. He returned in 1996 to reconnect with those he had left behind. A book of two hundred portraits by Chao, Something Went Wrong, has been published by Nazraeli Press. He now lives in Washington, D.C. “In the summer of 1996, I made plans to return to my home country of Burma. When I was unable to get a visa, I went to the Thai-Burma border and visited a rebel camp set up by the Karen National Union. There I met and photographed exiled politicians, ethnic rebels, and students of the democracy movement. They were all working together to bring an end to military rule. A few months later, the Burmese government, in its effort to curb insurgencies in the area, over-ran and torched the camp.”