I have always been attracted to professions for which I have little talent. Yes, that includes writing, and no, this isn’t false modesty (Say it isn’t so!). Nor do I feel sorry for myself (most of the time). Seen now from my platform of fifty-seven years, this odd propensity, this drift toward arenas where I am not necessary, seems like simple bad luck. Like being born in Cleveland.

For a long time (as Proust might say, we’ll get to that in a second), I wanted to be a drummer. I don’t know where it came from—my parents weren’t musical—but that winter when I was thirteen, I tapped and tinkled on my mother’s glass night table (using only the best of the family silverware) to the Beatles’ “It Won’t Be Long,” Duane Eddy’s “Mr. Guitar Man,” the Beach Boys’ “409.” Those are the ones I remember. The Ventures, a strictly instrumental band, did a song called “The McCoy” with a drum roll at the end of every twelve bars that made me nearly hysterical with excitement. I wanted to fire a gun out the window or throw myself down the stairs. Tap, tap, tap went my little silver knives, the blades dancing along the glass. Sometimes my brother stuck his head in the door; he wasn’t crazy back then, just older and bigger and calmer and admirable. He looked in, he watched me for a moment (I loved that part), and then, quietly closing the door, he went back to his blue bedroom and listened to a baseball game on the radio.

The snow melted outside my mother’s bedroom, the ice fell from the eavestroughs in the late afternoons, and the Beatles released “I Saw Her Standing There.” (“One-two-three-four!” Was there ever so irresistible a beginning to a song? ) By now, I was playing on books with real drumsticks. I played all the time, after school, after dinner. But it was peculiar. I wasn’t very good; I couldn’t “work things out” the way other drummers could; they’d hear a snappy, left-hand pattern on a record and reproduce it, beat for beat. It was like magic, like watching someone levitate. (It was talent.)

But I, for the life of me, couldn’t “work out” Ringo’s drum roll in the chorus of “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” You know that part, “I want to hold your haaaaand.” Was it, in fact, just a series of staccato beats with no hand-over-hand succession? Or was it something else? I still can’t figure it out.

Back then I went to a private school which entertained the conviction that young men of the “right sort” needed a taste of military training. You marched, you learned how to take a rifle apart, how to snap to attention, to salute, how to present arms. You put on a horsehair uniform and three times a year you paraded down Yonge Street, all these rich little pricks marching in lockstep.

I joined the band. That’s where the bad boys went, the insolent, the untrainable, the unmusical, the sociopathic. While young boys with faint moustaches paraded across the green fields of Upper Canada College, the band “rehearsed” in the basement of the school. Have you ever heard twelve snare drums playing the solo from “Wipeout” at the same time? But here’s the hook. Being a “rock ‘n’ roll” drummer, I figured I was doing them, the band, a favour, slumming a little with the less gifted, less electric personalities of the school. Like Jesus among the Nazarenes, I was in that world but not of it. But then a painful thing happened. That October, when it was time to choose four drummers to front the band (with all the rest hidden behind in nowheresville) for its first parade down Yonge Street, the bandleader held a competition down there among the broken chairs and coverless hymn books. You stood up, you hooked on your drum, did your thing, then sat down.

I came in fifth. Fifth! The second row, in other words. The fucking “B” team. To make things worse, when I complained, the bandleader, a boy with violently swept-back hair who played seventeen different instruments, all well, said (one never forgets a childhood slight), “Gilmour, you don’t seem to have the natural instincts of a drummer.” He didn’t stop there. “You don’t seem to understand where a drum roll belongs, even when you’re kidding around.” Hang on. Life hadn’t put down the horsewhip yet. Those guys who did make the front row? They didn’t practise for hours on their mother’s night table; they didn’t sit in the basement at home trying to work out the 5/4 bass-snare syncopation in Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five.” No, no. One of them went on to own a highly profitable string of slaughterhouses in Calgary. The other did time for shooting a man in the face with a shotgun during a “drug hassle.” This was my competition.

I read somewhere that Ernest Hemingway wasn’t an especially bright fellow; he had, so the article said, a completely average IQ, and owed his phenomenal success in literature more to willpower than to talent or brains. I’ve always found that factoid, true or not, reassuring. It was one of the things that made me decide to go to acting school in New York. But there was another reason as well, to be honest.

When I was twenty-two years old, I saw Last Tango in Paris at the old Uptown theatre in Toronto. It was 1972. After the movie I walked up Yonge Street, speechless. My girlfriend, a passive-aggressive with a minor speech impediment, nattered on about this and that in that little-girl voice of hers. She didn’t like the movie or Brando’s character. Thought guys like him were “thellfish.”

“Shellfish?” I inquired sadistically.

“thellfish! ” (We were getting near the end.) As for me, I had never been so stirred, so affected by a movie before. It was as if someone had glimpsed the inside of me and put it on the screen. The music, the lighting, Brando in that long coat, it made me long for another life. It made me want to be an actor. (It was only years later that I understood I wanted to be in the movie, literally, as opposed to being “in the movies.” Big difference.)

I saw the movie thirteen times, Marlon Brando lying on the floor of an apartment in Paris, talking about his childhood (“We had a big black dog named Dutchy. She used to hunt for rabbits in that field . . . ” ), and I thought, I can do that too. All I need is a camera and a girl like Maria Schneider.

So that fall, buttressed by a small inheritance, I hopped on a plane and flew to New York. I took a long-term room in the Chelsea Hotel and signed up at a pretty good acting school, the H. B. Studio down on Bank Street in Greenwich Village. But what became clear to me very soon was that I was surrounded by authentically talented people. They didn’t just have a “dynamic personality”; they could sing, they could dance, they could do breathtaking imitations of Al Pacino (a school alumnus) and Steve McQueen (another alumnus) in the washrooms and hallways. What I could do, what I could only do, was sit in front of a scene-study class, frozen with terror, and recite Ibsen in a voice not my own—all of which gave me, so my drama coach said (in tones I now reserve for children), a “certain intensity.”

The coup de grâce came a few weeks later when I took a “break” and flew back to Toronto. I was going to stay for the weekend, but one thing led to another and five or six days later I was still in town. It was early November. I was taking a shortcut through the university campus when I ran into a young man, my age, who had graduated from university with me. He had grown a red beard since then and developed a slightly English way of speaking, jerky, as if he were tripping, almost involuntarily, from one brilliant aperçu to the next. “A bit of a theatre man,” he was now. What was I up to? In a few moments I described an actor’s life in Manhattan which didn’t in the least resemble mine. (Mine consisted largely of reading show-business biographies in my hotel room.)

“Do you know Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker?” he asked. “We’re looking for somebody to play the older brother.” Did I want to give it a go? I agreed on the spot to “give it a go.”

I was, after all, a “New York actor” with seven scene-study classes to my credit. I bought two paperback copies of the play and hurried to see my nephew. He was younger than me and still very impressed with me. A perfect person to rehearse with. But when I arrived at his second-floor apartment above a pizza parlour, he wasn’t there. His roommate was, though—a burly, unkempt young fellow known around town as “the Bear.” I quickly outlined my good fortune, explained my haste; the audition was the following day. Could he, the Bear, give me a hand? He shuffled over to a ripped armchair (beside which stood a tower of paperbacks) and sat down. “Okay, you’re going to play the tramp,” I said, “and I’m going to play Aston, one of the brothers who brings the tramp back to his flat to stay for a few days. Got it? ”

“Why does he bring him home?” the Bear asked.

“Don’t know. Doesn’t matter.” We started, the Bear hesitantly. Jesus, I wondered, can the guy even read? But soon we came to a small speech where the tramp talks about why he left his wife. “Fortnight after I married her, no, not so much as that, no more than a week, I took the lid off a saucepan, you know what was in it? A pile of her underclothing, unwashed.”

Something curious was happening. I began to feel that I was in the presence of a sour, deceitful, slightly crazy loser. But when I looked up, it was just the Bear hunched forward in his chair, holding the book between his legs. We went on. “Who was this git to come up and give me orders? We got the same standing. He’s not my boss,” the Bear growled. And as he read, it seemed as if he was growing in stature, in weight, whereas when I spoke there was a sensation of diminishment, a small unconvincing voice that might well have been saying, “Hey kids, we can have the party here!”

To mollify my escalating discomfort, I suggested we switch roles; I’d read the tramp, he could read the brother. We began. Suddenly from across the room I heard the voice of a mean-mouthed prick. I understood in a flash why the brother had brought the tramp home. He was a recreational sadist; it was for entertainment. The Bear had shown me! Me, a New York actor, slumming in a college production. I had been in the presence of talent before but I had never had so precise, so unexpected a brush with it before that afternoon.

I never went back to acting school after that. I never phoned in, I never dropped out formally. I just vanished. In fact, I didn’t go back to New York for many years. I left all my stuff (Cavett, by Dick Cavett) at the Chelsea Hotel. I may have gone to the Pinter audition the next day, I think I did, but my heart wasn’t in it. Which was a good thing. I might have wasted quite a few years there as a half-assed actor. No, the Bear showed me the real thing that afternoon. He was the one who should have gone to New York, not me. But he didn’t. Something else I’ve learned along the way: just because you’re good at something doesn’t mean you have to do it. Last thing I heard, the Bear was a happily married man who ran a health-food store in Vancouver.

I wish I could say that when I settled on writing, when I managed finally to give it some time and actually did it (as opposed to telling girls at parties I was a writer), there was a click somewhere in the universe and everything fell into place. But that didn’t happen.

For a few years in my late twenties I looked in the mirror and thought I saw Scott Fitzgerald looking back at me, but that didn’t last long. Very soon it was Ringo’s drum roll again. I found myself reading novel after novel—good ones, bad ones—feeling a kind of cold hand clutch my heart, a hand that said, “You can’t do that. Or that. Or that either.”

But I went on to write books anyway (I was compelled to), a half-dozen short novels. Some did okay, others sank faster than a new Chevy Chase movie. None of them did as well as I’d hoped. But more important, none of them was as good as I thought they were when I was actually writing them. Once, when I was giving a reading in a bookstore in an American city, I looked at the small audience, the empty seats, the stack of my books waiting hopefully at the signing table, and I had a not-so-small, not-so-pleasant “moment.” I suddenly understood that I had a completely average talent, that I was never going to be a front-ranking writer, and that if I did better than some of the competition it was because I worked harder. I realized with diamond clarity that my work would vanish when I did, that I had (and this seemed particularly painful) kept my novels, my writing “career,” aloft over the years by the force of my personality alone. But if I stepped away for even a second, it would crash, all of it, to the ground.

You’d think this might have been a moment of liberation, that afterwards I was a less tormented man. But that’s not true either. A few years later, I watched with dismay as another freshly published novel shot heavenward for a hundred metres, sputtered, then sank slowly back to earth. I lurched about my porch that summer with a gin and tonic in my hand, saying over and over to my wife, “They fucked me again!”

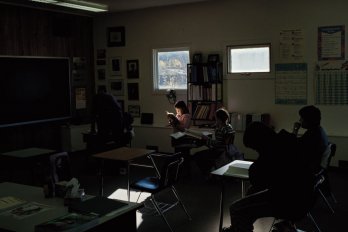

So why does anyone keep at it, these things you’ll never be quite good enough at? Why play the drums if you can’t even get the roll in “I Want to Hold Your Hand” right? Why act if you can’t do it like “Jack” or “Bobby” or “Dusty?” I remember once when I was about fourteen, maybe fifteen, I played in a little band, three guitars and drums, and one Saturday night we played a dance for a Christian youth group. There weren’t many people, a few boys, a few girls way at the back of the room, but it was eight o’clock. Time to start anyway. They turned down the overhead lights; someone turned on a small lamp, which fell over the drums and the amplifiers in a mysterious red glow. The lead guitarist tapped his foot uncertainly, One-two-three-four. I struck my tom-tom, then struck it again, and we fell into an instrumental version of “Needles and Pins.” What happened next had nothing to do with the Beatles or making a record or hoping to be famous. As our little band found its footing and settled in, I could feel my young soul reaching inside my chest; it was reaching upward, as if it were trying to leave my body, as if it were trying to sail forth from sheer joy alone.

Sometimes when I come downstairs in the morning and I look at my writing desk, papers scattered all over the place, books open, I feel the most inexpressible joy. I know that later in the day I’ll walk into a bookstore and they won’t have any of my books. Or worse, the books of somebody I loathe will have a prominent place in the window and I’ll feel as if I’ve eaten something poisonous. I know I’ll run into somebody next week who’ll pull me aside to tell me about a bad review, or a thin woman at a cocktail party will tell me that she got “halfway” through one of my books. I know all this will happen. But at that moment, coming down those stairs, I think, this is it, this is my life. And I feel like that young kid on the drum kit. As if I have finally arrived in the present, that the universe has a point and, for a few private, ecstatic, stolen seconds, a centre. That I am—what is the word that dies the moment it reaches your lips? Ah yes. Happy.