When Ottawa unveiled the design of its new central library in 2020, the mayor promised it would be “more than just a building with books.” The design of the $192 million edifice, to be split between the city’s main library and Library and Archives Canada, “connects the facility to Ottawa’s rich history and natural beauty,” the city elucidated. “Its shape is reminiscent of the Ottawa River; its stone and wood exterior reflects the adjacent escarpment and surrounding greenspace.”

“I feel like crying,” one onlooker told the CBC. “It’s a magnificent building.”

Not everyone was so generous with their praise. “It looks like any recent university campus build. I was hoping for better,” one commenter on the CBC’s Facebook poll wrote. “I’m indifferent. It’s pretty beautiful, but it’s a colossal expense that could be put in a much more cost-effective building,” another noted. Others saw the price tag and wondered why the city was bothering at all: “Giant waste of tax dollars to pacify a very small number of people and mostly just the employees. Times have freakin’ changed people!!!”

Since then, the Ottawa central library’s price tag has ballooned by nearly 75 percent, for a new total of $334 million—including $28 million for a parking garage.

All of this, dear readers, is why Canadians cannot have nice architecture.

Beautiful spaces invite public participation. Think of the places you love most in your community and consider how they make you feel. What comes to my mind are memories of roaming the narrow corridors of Diocletian’s Palace, in Croatia; enjoying vino rosso on the lively piazzas of Rome; watching fireworks explode over the Old Port of Montréal. These are spaces built for people. All kinds of people want to use a lovely library, bike through a lush park, visit a poignant outdoor monument, even use the rooftop patio of their condo building. Consider our COVID-19 experience, which has seen people clamouring for communal outdoor spaces where they can be safely together. When all this is over, buildings will again be gathering points. Don’t we deserve beauty?

There are scientific reasons, too, for encouraging better aesthetic standards. Studies have shown that certain design elements—windows in offices, for instance—can have positive impacts on our health. (Daylight exposure improves well-being, mood, and quality of sleep.) David Fell, a scientist studying timber in British Columbia, has found that wood in rooms also lowers stress.

Today, barring the newish Halifax and Calgary central libraries (which opened in 2014 and 2018, respectively), one wonders whether the average Canadian could name a building constructed in the past thirty years the country could be proud of. This isn’t only a matter of aesthetics: for a country that is ostensibly concerned about climate change, we don’t do much to push the envelope on environmental design. That’s not to say there are no good, sustainable modern buildings in Canada; there are always exceptions to any rule. They certainly are exceptions, though.

So I canvassed architects, architecture critics, and architecture professors and asked: Why is so much of Canadian architecture so ugly?

“Ça part fort. What a start,” says architecture critic Marc-André Carignan, laughing nervously into the phone. He takes a deep breath before continuing. “Well, it depends. It depends on the era we’re talking about. If we go back to the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s, we saw an enormous number of innovative modern buildings, in housing and in other areas,” Carignan says in French. And it’s true that the modernist era was incredible for architecture, abroad and in Canada. The movement that produced icons like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum, in New York, and Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, near Paris, also inspired Montreal’s Lego-like Habitat 67 and more discrete gems like Bauhaus master Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s gas station, which in 2020 was repurposed into an intergenerational community centre in Montreal. The era also yielded a number of brutalist treasures, some of which admittedly still possess real charm and character.

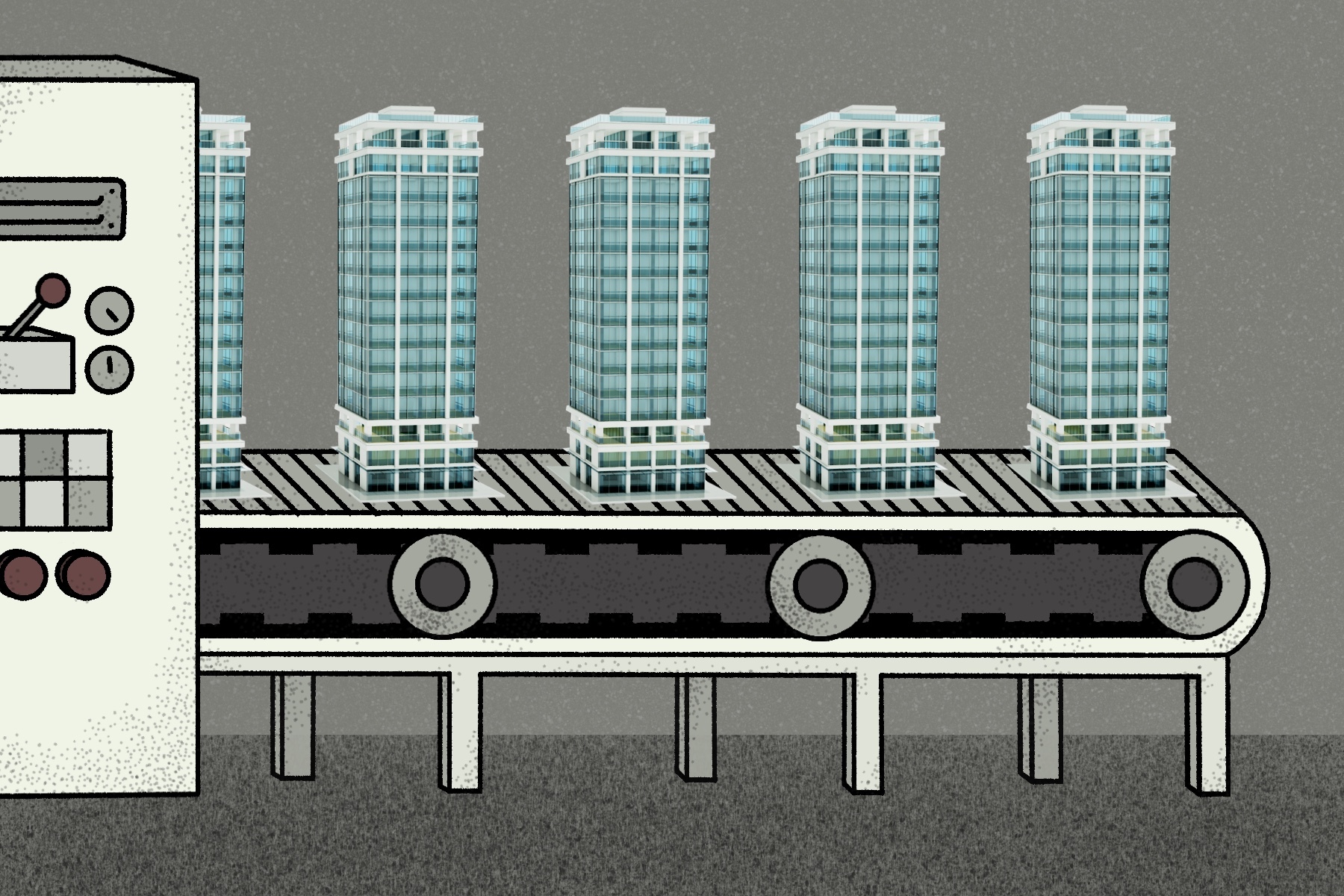

Since modernism, though, architecture in Canada has taken a real nosedive. One possible explanation, suggests architecture historian and critic Hans Ibelings, is increasing suspicion of government spending—especially if it involves frivolous design flourishes. Then came sprawling suburbanization, the economic recession of the 1980s, the spread of the megamall, and the fast-and-furious office tower and condo boom that cast a shadow of sameness across cities. In many places, officials ceded visions for cities to private developers, which is why you can now find massive condo towers in low-rise neighbourhoods.

Sometimes it feels like “design” has become a dirty word. As Ibelings puts it, “I sense a kind of indifference for the built environment.”

Can that really be true?

The reason Canadian cities look so blah compared to, say, European ones is only partly because ours are much younger. After all, Rotterdam was almost totally flattened by German bombs during the Second World War, yet it became beautiful again by making purposeful, daring design choices for its central train station, museums, a culinary market hall, the Erasmus Bridge, and other constructions. We could blame it on not having a home base of exceptional architecture from which to draw inspiration—but that’s not quite it either. The architect community is international, and European firms bid frequently to build in Canada.

Even the United States has more compelling architecture than Canada, particularly in its big cities. Chicago’s gorgeous Millennium Park, for instance, was the result of a public-private partnership that relied heavily on the philanthropic sector. Wealthy individuals, as well as foundations and other organizations, pitched in $220 million (US) for the park and an adjoining arts theatre—almost half of the total cost of the project. Its most recognizable feature, a $23 million bean-shaped mirrored sculpture, was privately funded through donations. In Canada, philanthropy is most generous toward hospitals, schools, and the arts.

When it comes to architecture—and, truth be told, a lot of things—University of Calgary architecture professor and author Graham Livesey suspects that Canadians don’t want to make a fuss. “I don’t think Canadians are any less informed than anybody else in the world. I mean, we’re fairly educated, we’re fairly sophisticated, and we travel,” says Livesey. “I mean, we’re not stupid.”

He disagrees that Canadian architecture is uniformly ugly, although he does call a lot of it “mediocre.” Still, he points out that there are pockets of excellent design that partly redeem us. And some cities do a good job of highlighting the natural landscapes abutting the built environment. Some even take design risks. “You have tiny little rinky-dink towns in Quebec that are building beautiful libraries, performing-arts centres, and often with relatively young firms,” he tells me.

“But,” he continues, “I think Canadians—and this is something that sort of drives me nuts, and I think it’s not just particular to [architecture]—we’re just a bit passive, right? I mean, you could say the same when it comes to the environment. We’re really not doing that much for the most part, and Canadians aren’t really demanding that their politicians do very much either.”

There’s a lot of truth in Livesey’s estimation, but I suspect our commitment to accepting “good enough” isn’t merely about a lack of empowerment or abundance of ignorance. It’s also about our Kafkaesque procurement processes and how our local governments often hand cities over to private developers. Fundamentally, though, it represents our aversion to risk. Why rock the boat when something “safe,” functional, and cheap will suffice?

“Architecture” itself is a subjective term. We use it to label skyscrapers, artistic-looking pavilions, museums, libraries, train stations, and other public buildings. The weird-looking new Canadian headquarters of an international corporation probably counts. Some private homes certainly count: for instance, the midcentury modern homes designed by the late James Strutt in the capital region are architecturally beautiful. But does a Home Depot constitute architecture? What about a new midrise that is built to match other ones already on its block? Or a townhouse community where all the homes look the same? So little attention is paid to architectural significance, leaving our cement-and-drywall castles bereft of uniqueness and joy.

We can’t even blame the weather for our approach to design. Norway has cold winters too, but it has somehow managed to create an innovative movement where structures are built or renovated to produce more energy than they consume (called “energy-positive building”). And the buildings are beautiful too.

Not here, though. “The predominant approach to the design and construction of buildings across Canada has been ‘build cheap, maintain expensive,’” write Ted Kesik, Liam O’Brien, and Terri Peters in a 2019 design guide for multi-unit residential housing.

In many instances, “build cheap” also means “build ugly”—not because good design necessarily costs more but because we have conned ourselves into believing that it does. In reality, good design simply means making more creative choices with the money you have—something that is simply beyond the capacities and capabilities of the people with the rubber stamps. In many ways, our devotion to fiscal conservatism has caused us to settle for buildings that don’t meet even the most basic standards of environmental responsibility. Kesik et al., in their guide, lambasted building designers for allowing a generation of drafty, poorly insulated public housing to be built.

While Livesey isn’t so cynical to think that Canadian architecture as a whole is a chore to look at, he sees many newer private-sector buildings suffering from similar ailments: too much glass, cheap building envelopes, subpar insulation, uninspired design. Canada’s downtowns are still stuffed with cranes piecing together gleaming towers with floor-to-ceiling glass—a design choice that sucks up excessive amounts of electricity in both the summer and winter months. Private developers push for this kind of design because it is relatively easy and inexpensive to construct; it almost always get approved by cities; and when combined with cheap materials, it is the quickest way to get returns into the pockets of promoters and investors.

These motivations come at a cost. In 2014, the CBC reported glass panels falling off the facades of newly built condo and hotel towers in downtown Toronto, including the Shangri-La luxury hotel, where the most basic room goes for a minimum of $575 a night. In another Toronto high-rise, tenants contend with wildly fluctuating water temperatures seemingly due to improperly installed valves. Then there’s Vancouver’s enduring leaky condo crisis, in which tens of thousands of homes built in the 1980s and 1990s have been flagged for water leaks.

Livesey says developers shoulder only some of the blame, though. Subpar building codes and wayward procurement procedures poison our approach to civic design. And even beyond the politicization of architecture, in which a city council with no taste at all can decide how a city looks, the market still dictates most of what gets built. “Canadians accept a lot of this,” he says.

Why we accept it is a patently Canadian phenomenon: our national psyche has us much more interested in checking boxes than in taking chances. Our standard process for contracting buildings often gives projects to the lowest bidders, even if a vastly more beautiful design is just a little bit more expensive. We have become so devoted to frugality and bureaucracy, and are so readily appeased by basic functionality, that we have lost the fortitude to take and demand risks, even if the outcome could be the most beautiful thing we’ve ever seen.

Many Canadian architects don’t like how Canada does design. Often, though, they feel like they’re screaming into the void.

Much of Canadian construction is selected through the Request for Proposals (RFP) process. That includes public buildings: the libraries and city halls and arts institutions and civil service offices that are commissioned by governments and that could be prestige projects if we really wanted them to be. An RFP is simply a way to solicit firms to bid on a project: you describe what you need built and the relevant criteria (budget, site constraints, and so forth) and interested parties submit proposals to build it. Once the application window closes, all bids are then funnelled down to the selection jury, which scores the candidates. RFPs typically prioritize competency and technical details in this assessment. First, how qualified is the bidding team? And how will it approach the project? Then it comes down to cost.

Ottawa-based architect Toon Dreessen has encountered a lifetime’s worth of requests for proposals, and he’s rarely met one he liked. Many, he says, are poorly written or structured and are composed by procurement officers who are usually not architects or designers and may have no real concept of what makes a design proposal great (or not).

Dreessen says he once lost a bid for an environmentally friendly police detachment in the Arctic because his proposal went so far beyond the RFP’s requirements for energy efficiency that the judges didn’t know how to score it. That experience, like many others, taught him that many customers are often interested only in the optics of affixing a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) green-building certification on their projects. That’s a shame considering buildings are responsible for 17 percent of Canada’s and 39 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Worse, he says, the procurement process rarely invites creativity because the top competitors left in an RFP competition have equal technical skill to execute the project—meaning the core differentiator is almost always price.

As a resident of the nation’s capital, Dreessen has butted heads with all levels of government over their shared fondness for cheap, listless public architecture. While he has his qualms with local authorities’ lack of vision, the feds share some of the blame for how Ottawa looks. “The federal government has been shy about making really spectacularly beautiful buildings because they don’t want to get pilloried in the press. Their tendency has been to make fairly functional, reasonably inoffensive, generally mediocre buildings. And those buildings then set the standard,” says Dreessen. “Because why succeed and produce a jewel when you’re in a sea of mediocrity?”

He is part of a cohort of architects who believe a different way of selecting new buildings—design competitions—is one way to fight that tide. It’s an approach with a long pedigree: a war memorial on the Acropolis of Athens (competition held in 448 BCE), the dome of the Florence Cathedral (1418), Rome’s Spanish Steps (1717), the White House (1792), and Britain’s Palace of Westminster and Big Ben (1835) were all the fruits of design competitions. Design competitions are often open to the international architecture community and, in contrast to RFPs, tend to prioritize design, ethos, and innovation over cost.

National and international competitions have led to the construction of some of the most influential buildings standing today. In 1922, the Chicago Tribune received 260 submissions in its international design competition to build its iconic neo-Gothic headquarters. An open design competition in 1956 yielded the design of the Sydney Opera House, in Australia. Zaha Hadid, a groundbreaking architect whose firm continues after her 2016 death, mastered the art of delivering daring, futuristic buildings in design competitions.

Another option is a hybrid competition called a qualifications-based selection, in which the pool of firms vying for the contract is narrowed down by assessing their overall practices. It often includes vetting whether the firm has vision and the right technical skills and whether it can meet deadlines and communicate properly—some of the softer elements that an RFP has a hard time reading. Each firm then gets some money to put together comprehensive design proposals. It can be a more time-intensive, iterative approach as applicants get whittled down to a shortlist and then provide more detailed drawings. One winner is eventually chosen, based not only on cost but also on creativity, merit, and experience.

That’s the process by which Calgary got its award-winning central library. To Kate Thompson, president and CEO of the Calgary Municipal Land Corporation, which oversaw the library’s design and construction, the added time and effort was worth it. “I see a lot of people focusing a lot on ‘on time and on budget,’” she says. She likes to add “on quality” to the mix. “Nobody really remembers the date it opened,” she says, “but they sure remember how they feel in the space two years later.” Prior to COVID-19, the library was busier than ever, hitting the 2 million visit mark in early 2020.

Even more striking is that the design of the building has shifted people’s sense of what goes on inside. For a long time while it was still in the planning and construction stages, Thompson says, “every single dinner party or event I was at, people said, ‘What are you doing building a library? Aren’t libraries dead? And why is it so expensive?’” People shut up after the library opened, in 2018, to global adulation, however. “Suddenly, the discussion was, ‘Wow, that’s really cool. Did you know that was in the New York Times?’”

Carol Bélanger is a rare creature: a city architect. While it has precedent in Europe, his role in Edmonton is distinct in this country—none of Canada’s other largest cities have someone like him. Bélanger’s job is to be an advocate for architects, design excellence, and publicly owned buildings old and new. His office oversees how new construction is commissioned, ensuring greater consistency in the selection process. He is essentially a go-between for the public, the city, and architects, and he has the capacity to speak to each constituency in its own architectural vernacular. “It’s like having an educated buyer for the citizens,” he says.

Bélanger became the city architect eleven years ago, not long after former mayor Stephen Mandel famously said his tolerance for “crap” architecture was zero. Bélanger’s vision and leadership have given Edmonton a number of spectacular buildings and public spaces that set the city apart from so much of Canada. The architect’s favourite project was the result of an international design competition: five parks, five pavilions. The one at Borden Park went on to win a Governor General’s Medal in Architecture—Edmonton’s first in twenty-six years.

The others I spoke to for this story think the advocacy work done by city architects would help dial down developers’ design influence and make more cohesive visions for cities. A number of them also believe Canada needs a national architecture policy, which would explain the benefits of well-designed environments and give guidance to governments on how to make better use of their spaces. This would help make city leaders think more critically about the social and environmental roles of architecture and engage more collaboratively with the architect and urbanist community as they develop new projects.

A policy is great, says Montreal architect Ron Rayside, but he’d like to see architects and architecture associations—normally very cautious entities—go even further to advocate for design excellence and better dialogue between architecture and the public. “I think professional associations should get involved in public policy and make statements and be involved in all kinds of issues,” he tells me, pointing out that professional associations often limit their advocacy to defending their members and industry. “They’re pretty cautious, traditionally, saying, ‘Well, that’s not really our role.’ Well, it is.” Rayside wants more political stances to defend the public’s interest; without them, he says, “they’re really missing the boat because they’re not using their knowledge in a way to make society a better place.”

Would more empowered architects truly make a difference when keeping tabs on Canada’s pocketbook is a national pastime? Could they prove to passive, suspicious, and/or cheap Canadians that good design exists and that it is an expense worthy of our tax dollars?

We can hope, but we shouldn’t hold our breath.