When the graphic novel Skim (2008) opens, the chapter title tells us that it’s fall. But the heading is almost redundant. Jillian Tamaki’s ink rendering of the wind—crisply whipping the young women’s hair and skirts, and sending oak leaves cascading to the ground, where they crunch underfoot—is enough to convey a sense of the season’s chill. The tableau is so show-stopping that turning the page to find it feels like a dramatic act: an unveiling, a revelation.

Here, and in other lavish spreads, Tamaki stages the action and emotion that her cousin and collaborator, writer Mariko, leaves unarticulated. The book recounts a few months in the life of Kimberly Keiko Cameron (a.k.a. Skim), a goth teenager in 1993 Toronto who dabbles in Wicca at the lonely margins of her all-girls private school and whose life capsizes when she falls into a dalliance with her free-spirited, long-skirted English teacher. The boundaries of each author’s duties are porous: Mariko’s sparse words leave empty spaces that images must fill, while Tamaki’s eloquent pictures help narrate the coming-of-age tale.

Many felt this sophisticated, intuitive approach to illustration was overlooked when, in 2008, Mariko was nominated for a Governor General’s Literary Award for children’s literature, but Tamaki was left out of consideration. The snub galvanized a comics community that had grown exasperated by the way cultural gatekeepers misconstrue their medium. Traditional picture books take existing text, such as a nursery rhyme or folk tale, and bring choice passages to life in a series of disconnected images (it’s clear, for example, that Dennis Lee wrote the children’s poems in his 1974 classic Alligator Pie, while Frank Newfeld provided the accompanying art). A graphic novel, Skim was different. “Jillian’s contribution to the book goes beyond mere illustration,” insisted cartoonists Seth and Chester Brown in an open letter to the GG Awards that featured prominent comic creators as co-signatories. “She was as responsible for telling the story as Mariko was,” they wrote.

The controversy is now years in the rear-view—Skim has become a staple in university courses on Canadian literature, and the GG Awards have since rejigged their troublesome category to honour collaborative teams as well as individuals. In retrospect, however, the dust-up can be seen as a sign of why Tamaki’s rise has been so trailblazing. She confounds expectations because she takes techniques often tied to writing—characterization, plotting, irony, metaphor, even cadence and rhyming—and uses them to sequence images and drawings. In their subject matter, too, her books are about breaking out of strictly defined categories. Skim is, among other things, about whom you’re allowed to love. And her and Mariko’s celebrated follow-up, This One Summer (2014), set during a vacation at a beachside retreat, features the crises of maturity of a girl named Rose, who longs to be a part of the teenage world, with its passions and sexual fumbling.

Comics are often cast as a hybrid art. Literature asks readers to create their own mental images, and painting encourages viewers to construct their own narratives—contemporary cartooning is a peculiar amalgam of the two.

Boundless, Tamaki’s new book of graphic short stories, inhabits a similar shifting terrain—blurring style and substance, form and content. Using maximalist flourishes to tell minimalist accounts of women’s lives stripped bare, it confirms that Jillian Tamaki, the go-for-broke illustrator, has always been a front for Jillian Tamaki, the consummate storyteller.

Tamaki started off as an illustrator, and was renowned early on for her technical mastery. Soon after graduating from Calgary’s Alberta College of Art and Design in 2003, she was already winning laurels for her gift for visual metaphor, her ability to encapsulate a book or magazine concept in one sumptuous image (in one of her later works for the New York Times, a portrait accompanying a piece on compulsive hair-pulling, each of the frazzled lines that makes up the subject looks like a strand of yanked-out hair). Her work with The Walrus has netted her several National Magazine Awards, and her resumé includes plum gigs from the likes of Penguin Books and the Criterion Collection.

Tamaki’s detour from a successful illustration career into the byroad of comics is uncommon—the rewards in comics are fewer and the prestige far less. “I wanted to make a comic, but I never really thought that I would be a graphic novelist,” the artist has said. Skim came about because a zine editor was commissioning comics from creators who were new to the form. Tamaki, who devoured Archie comics as a child and was struck by the sophistication of alternative cartooning when she discovered it in art college, was eager to try her luck. “It’s just my personality that I get bored and anxious if I don’t feel like I’m moving forward or improving,” she has said.

Still, for an illustrator, the switch comes with creative risks. The concision of a single image can get lost when ballooned into sequences. Her work, however, sidesteps this pitfall. In This One Summer, she uses single-image grace notes to evoke the rhythm of a summer’s day: each is part of a larger whole, rather than its own composition. The atmosphere of a lazy cottage afternoon—bugs zapping, a hose faucet dripping, girls passing time playing MASH—gets split up over several frames, the proceedings moving at a slow pace.

While she was painstakingly building the world of This One Summer, Tamaki also diverted her attentions to less time-consuming work, posting an online series of bluntly drawn, single-page gag strips that were collected in 2015’s SuperMutant Magic Academy. Her first full-length solo story, SuperMutant hypothesizes that prep schools for witches and paranormal teens, such as Harry Potter’s Hogwarts or Charles Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters, would be just as steeped in hormones, anxiety, and sophomoric tomfoolery as any real high school.

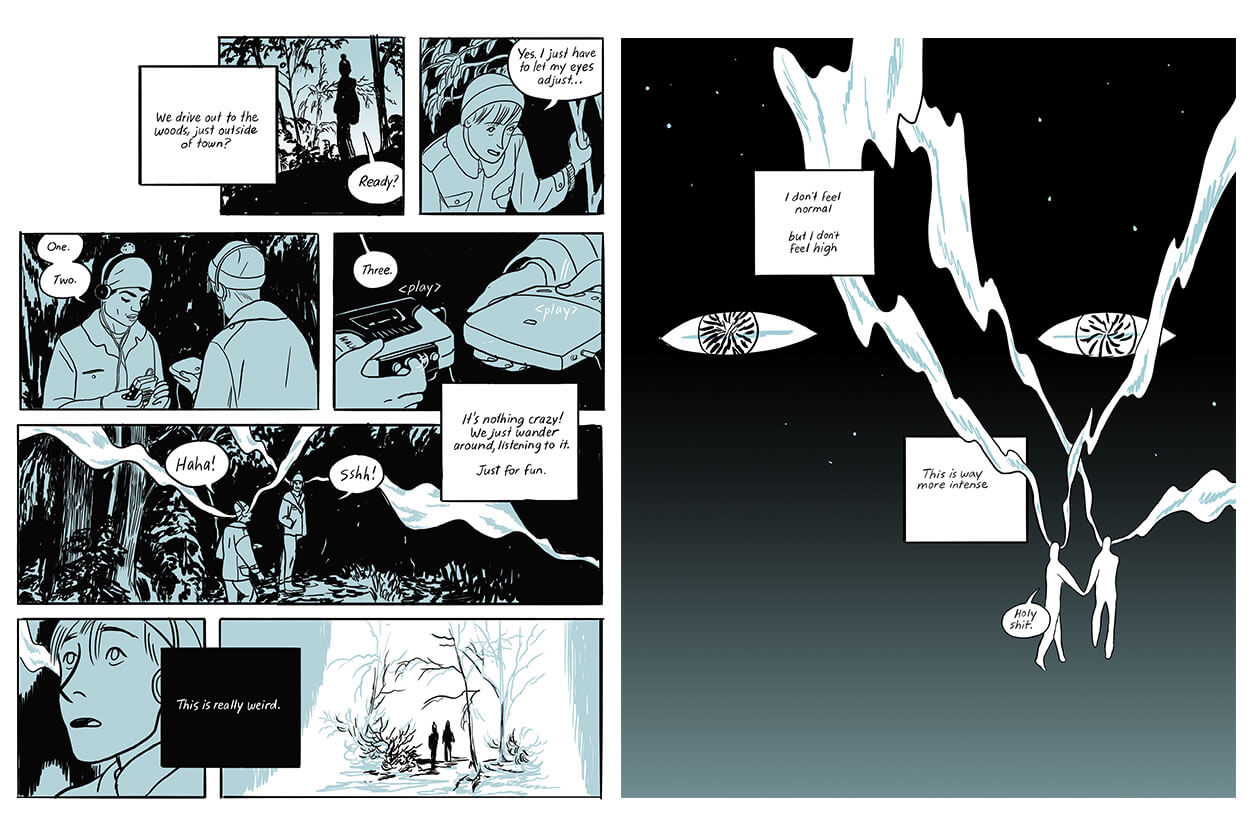

Tamaki links the prosaic and the preposterous with far more assurance in Boundless, which, for the first time, sees her focusing exclusively on adults (although there is one strip about birds, squirrels, and a housefly). Many comics in the book explore offbeat storylines. In “Half-Life,” a woman starts to shrink to nothingness; in “Darla!” a television show spices up the sitcom format with straight-up porn; in “Sex Coven,” an audio file anonymously uploaded to the web seems to have almost occult properties.

Throughout these disparate stories, Tamaki reveals an unmatched aptitude for visualizing the lives we live online, in part because she rejects any moralizing. We’re told of the existence of a “mirror Facebook,” where users can stalk alternate versions of themselves; of a curse that dogs the stars of a cult film, whose deaths seem to align with the love life of the narrator. But Tamaki doesn’t care about clarifying these mysterious circumstances. There are no epiphanies or explanations, just people forced to live with uncertainty. Tamaki’s characters get swept up within larger currents over which they have no control—from pyramid schemes to viral internet shadiness—and her emphasis on the individual, rather than on the system engulfing her, is part of what makes Boundless feel so raw.

Because she has parachuted in from a field outside of comics, Tamaki obeys no preconceptions about how cartooning should work. This means that she has remained mercifully divorced from the genre’s retrograde history. Virtuosic illustration in comics—where each composition is a heroic feat of line work—has long been perceived as the domain of male artists. Women making comics were often written off as having primitive skills, or as lacking professional polish.

“This scribbly stuff’s just a gimmick, right?” asks an art professor in one autobiographical strip by Aline Kominsky-Crumb. “Ya can’t really draw.” When Sylvie Rancourt tried to find an English publisher for Mélody, thinly fictionalized comics about her experiences dancing nude in 1980s Montreal, she was told that her drawing, “though charming, would not be well received by most American readers.”

Tamaki’s peerless craft puts the lie to that line of thinking. “I remember doing a panel or something with [cartoonist] Gabrielle Bell, who said that the only things that drive her stylistic choices are to make her drawings not look girly,” Tamaki told The Comics Journal. “And I think I might be the same way, subconsciously.”

Her work rescues the fully rendered style from the realm of the muscular and macho, investing it with feminist views on girlhood, maternity, desire, and infidelity. In Boundless, Tamaki’s avoidance of anything “girly” involves turning her fantastical tales relentlessly back toward the external facts of her characters’ existence—their bodies, jobs, partners, and homes. Tamaki refuses to let her inspired ideas become more intriguing than what they reveal about the women she creates. For stories that deal with life on the internet, her comics are remarkably corporeal and thickly textured.

Partly, this physicality derives from the fact that so many of these stories are about women who are forced to define and redefine their lives once they’ve crumbled. A figure from the opening story, “World-Class City,” could serve as an emblem for everything that follows: barefoot, wearing little more than a tattered shift, a thick rope of hair down her back, she literally peers over the edge of the page, anchoring the goings-on with her aloof but bulky presence.

Tamaki’s characters exist in this ur-woman’s shadow, each of them starkly exposed to the world, wondering at her place in her own story. In “Half-Life,” Helen must come to terms with her gradual disappearance. In “Sex Coven,” Raven must figure out whether she still belongs in the cult devoted to the audio file, years after the craze around it has peaked. And in “Bedbugs,” Angela must not only divest herself of all her belongings in the hopes of making her living space clean—but also engage in a moral cleansing, sloughing off all the excuses she’s used to justify her extramarital affair, confronting her behaviour nakedly, candidly.

The style of “Bedbugs” is the book’s simplest and sparest, but its story is perhaps the most complexly affecting. As Angela tries to pare her life down to something “compact and stripped of excess,” Tamaki likewise winnows her art down to a few careful brushstrokes, or to borderless panels that float in the white expanse of the page. The minimalist look of the images, however, can hardly tamp down the emotions that surge through the story.

One image from the tale stays with me. “Bedbugs” concludes with a close-up of Angela’s eyes and knitted brow: her features, drawn with expert, observant precision, are captured in an inscrutable and indecisive moment. The story, to this point, allows us to read any number of meanings into that Mona Lisa expression. Does it suggest relief, fear, sorrow, despair? Tamaki’s artistry—as an illustrator and as a cartoonist, and as someone who can seize on exquisite single images—leaves every possibility achingly open.

This originally appeared in the July/August 2017 issue.