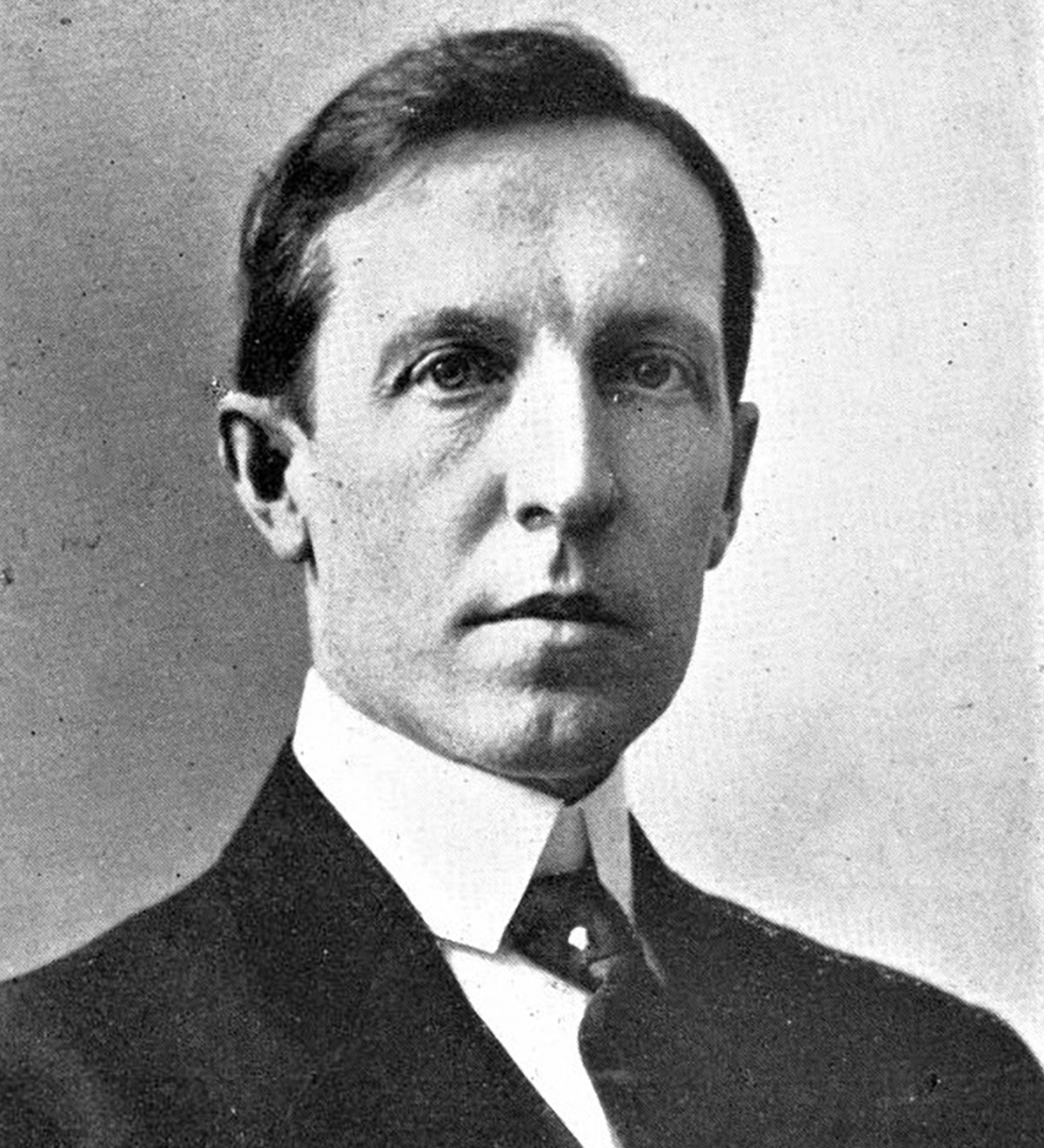

Throughout much of the twentieth century, a man who is now a byword for infamy was widely seen as one of Canada’s best poets. In 1982, when Margaret Atwood edited The New Oxford Book of Canadian Verse in English, she praised the “moral jaggedness” and “condensed tragedies” of Duncan Campbell Scott’s poetry and allowed only two writers, living or dead, more pages in her anthology. “His place is secure in the canon of major Canadian writers,” wrote the critic Robert L. McDougall the following year. Scott took the traditions of English Romanticism and immersed them in a northern wilderness. His poetry evoked the landscapes around him and the Indigenous peoples who lived there:

Quiet were all the leaves of

the poplars,

Breathless the air under their

shadow,

As Keejigo spoke of these things

to her heart

In the beautiful speech of the

Saulteaux.

Scott was, in fact, a central figure in Canadian culture. Both the University of Toronto and Queen’s University awarded him an honorary doctorate; a patron and connoisseur of the arts, he helped found the Dominion Drama Festival. Soon after his death, in 1947, Saturday Night magazine ran a tribute headlined “Great Poet, Great Man.” He received the extraordinary tribute, for a Canadian writer, of a memorial service in one of London’s grandest churches, where Britain’s poet laureate, John Masefield, gave a eulogy. Masefield stated that, as a young man, reading one of Scott’s poems “impressed me deeply, and set me on fire.”

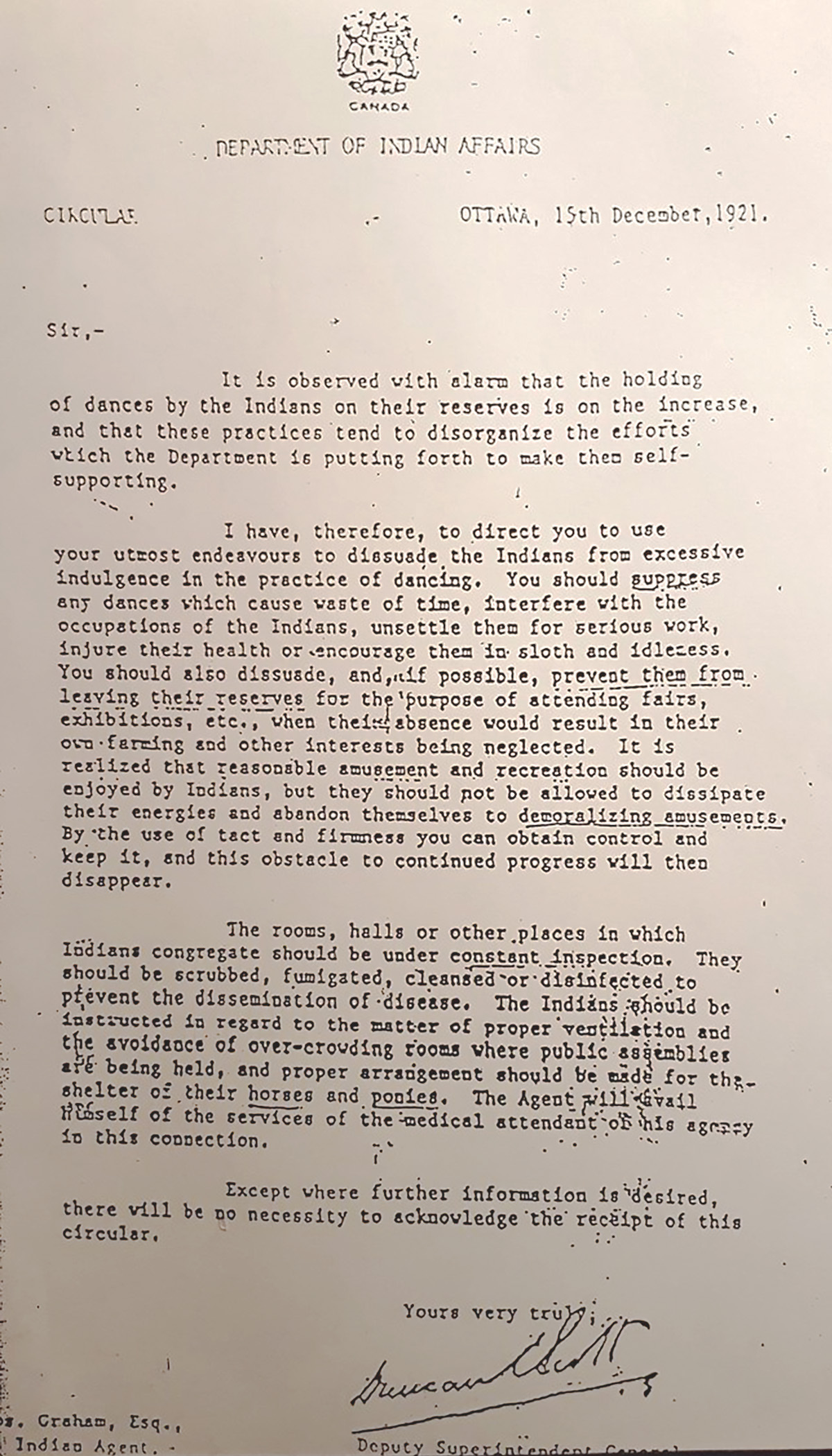

Yet today, seventy-five years since his death, Scott’s image lies in ruins. When the magazine The Beaver (now Canada’s History) asked a panel, in 2007, to name the worst Canadians of all time, Scott was among them. His disgrace has nothing to do with changes in literary fashion but with the work he did in his day job. As the long-time deputy superintendent general of Indian Affairs, the overseer of a residential school system created to strip Indigenous children of their culture, and the civil servant who declared that government policy aimed to “get rid of the Indian problem,” his name has become a source of shame.

Though he praised “the beautiful speech” of the Saulteaux people, Scott also did everything in his power to obliterate Indigenous languages and cultures. The writer who defined the role of the imagination as “to set up nobler conditions of living” was also a powerful bureaucrat who seldom lifted a finger to improve conditions for the Indigenous people whose lives he governed. The author whose lyrics could tenderly explore death also oversaw an expansion of the residential schools where many thousands of children died after suffering neglect, mistreatment, and abuse. He stands accused of facilitating genocide.

The person who has held Scott’s legacy most forcefully to account is Cindy Blackstock, a professor of social work at McGill University and the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society. Because of her activism, the plaque beside Scott’s grave now focuses on his damaging career in Indian Affairs, and the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada has put his designation as a “national historic person” under review. (Scott is far from alone: at least 187 historic places, events, and sites are being reexamined partly or wholly because of “colonial assumptions” in their descriptions.)

After a public challenge from Blackstock, the Royal Society of Canada, a national body of Canadian scientists and scholars, sponsored a 2021 collection of essays, Royally Wronged: The Royal Society of Canada and Indigenous Peoples, in which several authors confront Scott’s legacy. One of them, Carole Gerson, a professor emerita at Simon Fraser University, adroitly summarizes the reasons to read his poems and the difficulty of doing so: “If Scott had not written about Indigenous people, who appear in a very small portion of his total oeuvre, it would be easier to continue to appreciate his literary work as lyrical, aesthetic, stylish, and often very good.”

Although Scott ran the Department of Indian Affairs with glacial detachment, he fused emotion with grace in his best poetry—which is “unequivocally worth teaching,” says David Bentley, the Carl F. Klinck professor in Canadian literature at Western University. Bentley expresses dismay at the prospect of airbrushing Scott out of literary history: “It goes against the very fibre of my being to see that here.” Scott used what he knew of Indigenous peoples and culture as occasional subject matter; like nearly all white Canadians of his time, he believed they were fated to disappear by the process of assimilation. His sonnet “The Onondaga Madonna,” for instance, describes, “This woman of a weird and waning race, / The tragic savage lurking in her face.” The child at her breast, having a white father, is “the latest promise of her nation’s doom.” The poem forcefully expresses ideals, widespread in the past, that most today find repulsive.

Scott’s adherence to those ideals and the power he exerted in Ottawa mean that his memory is still under fire. Queen’s University and the University of Toronto are facing pressure to revoke the honorary doctorates they granted him long ago. Amanda Buffalo, an Indigenous PhD student at the University of Toronto, co-sponsored the petition there. “Our task at hand,” she tells me in an email, “is getting a prominent ‘historical figure’ who both advocated for and acted on genocidal objectives with respect to Indigenous People, defrocked by the U of T. This is one of many necessary steps in reconciliation.” A boilerplate reply from the university notes only that it is committed to making sure “these complex matters can be resolved appropriately and respectfully.” The Queen’s petition states: “Duncan Campbell Scott is responsible for cultural genocide. To honour such an abhorrent individual is to condone violence and murder.” In response, the university senate asked for an official review of his degree.

Is it possible to arrive at a nuanced assessment of a man who did so much damage and who wrote so well? As Scott’s downfall reverberates, the echoes may hold clues for how to think about other writers with a legacy of pain or villainy.

A ten-storey chunk of concrete brutalism on the campus of McGill University has been known as the Leacock Building ever since it was put up, in 1965. The name honours Stephen Leacock, who spent more than thirty years as a McGill professor and whose witty books of fiction were, a century ago, widely read across the English-speaking world. Though his fame has thinned of late, he still has countless admirers, and many of his works remain in print. They include Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town, a book of short stories that concentrate on flawed yet kindly Canadians of British descent. Mingling nostalgia with keen-eyed observation of human foibles, Leacock’s stories bespeak a wise, affectionate tolerance. “For my money,” Bentley says, “Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town is one of the really great books written and published in Canada.”

Leacock’s writings, however, are not all works of fiction. He was also a prolific author of popular history—nonfiction books containing passages that are now hard to stomach. He expressed scorn for people of Asian and African origin, and in The British Empire: Its Structure, Its Unity, Its Strength, he praised “the ‘white races’ whose superiority no-one must doubt.” His disdain for women was extravagant; in 1915, he scoffed that “the ordinary woman cannot do the ordinary man’s work. She never has and never will”—and added that “in point of morals the average woman is, even for business, too crooked.” On several occasions, Leacock attacked the Iroquois and Huron peoples, using language whose violence went beyond anything Scott ever wrote. Leacock’s opinions were not uncommon then, but his rhetoric could be particularly vile.

That rhetoric has drawn complaints for years. In Geist magazine, historian Daniel Francis characterized Leacock as “a misogynist and a racist.” “That a building is still named after him,” charged a columnist in the student newspaper the McGill Daily, “and that he is still touted as someone to admire speaks to McGill’s own colonial, sexist, and racist history.” Such attacks help explain a key detail of the announcement McGill University made last November: Gerald Rimer, a venture capitalist now living in Switzerland, would give his alma mater $10 million to renovate the aging Leacock Building; the Rimer family would provide an extra $3 million toward a new Institute for Indigenous Research and Knowledges. The institute is to be housed inside the Leacock—henceforth to be known as the Rimer Building.

“The University may rename an asset for several reasons,” explains Shirley Cardenas, a media relations officer at McGill, in an email, “including alterations to the asset (such as renovations) or at the end of the useful life of an asset.” McGill lighted on a deft way to eliminate a problem before it turned into a public embarrassment. In doing so, it is following the lead of other organizations linked to contested figures: the Canadian Historical Association, for example, which removed the name of John A. Macdonald from its signature book prize, and Toronto Metropolitan University, formerly named after Egerton Ryerson.

“I think it’s just horrible that a writer of that stature should have his name dropped by McGill,” says Bentley. But, with Leacock’s prejudices laid open on the internet for all to see, keeping his name on a building would be highly problematic. Perhaps in 1933 it seemed acceptable for Leacock to write, “It came to be the destiny of America that the whites cleared out the red men, and brought in the black men to work under white direction.” But terms like “red men,” “cleared out,” and “white direction” are seen differently today—and the deference once given to a pipe-smoking, suit-wearing, Scotch-swilling elite has vanished. It may be only a matter of time before Leacock’s fiction also loses its appeal as an “asset.”

“Revolt is essential to progress,” Scott, then the president of the Royal Society of Canada, told members at their annual meeting in 1922. He praised “the revolt that questions the established past and puts it to the proof, that finds the old forms outworn and invents new forms for new matters.” In an age of instant judgments, what new forms might we invent and what questions might we ask to help us remember uncomfortable figures from the Canadian past?

Time shows no respect for courage or beauty, the British poet W. H. Auden once observed, yet it “worships language and forgives / Everyone by whom it lives.” Will time forgive Leacock for his racist blustering? Will it forgive Scott, under whose authority Indigenous people went to jail for taking part in a potlatch or sun dance and who made sure First Nations communities couldn’t hire lawyers to represent them without approval from his department?

CanLit Guides—a website run by the Canadian literature team at UBC and aimed at undergraduates—offers no forgiveness. “It is important,” the guide states, “to remember that the beauty of a poet’s expression is itself an ideological tool: Sometimes saying racist things in poetic ways makes them seem all the more true . . . . By trying to schism the racism of Scott’s poetry from his poetic expression, scholars are ignoring how poetic form was being used as a tool for the dissemination of racism.”

While debates about artistic dishonour and shame are international, they are especially intense in Canada, a nation with serious historical guilt and few great writers. Perhaps genius can make it easier to absolve certain figures—and to keep celebrating them. Scott and Leacock were not authors of the calibre of Joseph Conrad (an anti-imperialist but also an out-and-out racist) or Flannery O’Connor (fiercely racist). One of America’s leading modernist poets, Ezra Pound, made hundreds of pro-fascist broadcasts from Italy during the Second World War; charged with treason, he spent twelve years in a psychiatric hospital after pleading insanity. But, during his confinement, his lengthy and erratically brilliant Cantos appeared from major presses. In France, the writer who took the pen name Céline—he was, if anything, even more rabidly antisemitic than Pound—is revered as an outstanding novelist; this year, one of his long-lost manuscripts, Guerre, was published to considerable fanfare.

The Canadian poet and philosopher Jan Zwicky argues that the situation is complex. “I’m absolutely horrified by Tolstoy’s view of women,” she says. (He idolized motherhood but excoriated childless women and spoke of women’s rights as a “remarkable piece of stupidity.”) “But War and Peace is an extraordinary novel, and reading it and thinking about it has deepened my life, made it richer. It has enhanced my feminism in complex ways. I would not want it pulled from the shelves.”

Unlike Tolstoy, Scott kept overt political debates out of nearly all his writing. But, if anything in his battered poetic legacy is worth preserving, the way forward may be to bring his twin careers into dialogue. Eli MacLaren, an associate professor of English at McGill, teaches “The Onondaga Madonna” and a longer poem by Scott in an undergraduate course; he also gives a lecture on residential schools and, after exposing the students to Scott, introduces work by the Mohawk writer Pauline Johnson, whose poems offer a contrary perspective on the Canadian past. “Purging and cleansing are little help,” MacLaren says. “What helps is deepening our understanding of all motives, hopes, perspectives, and events in our country’s history.”

“You can’t wish away what happened,” remarks Julie Rak, a professor in the department of English and film studies at the University of Alberta. “We can’t change the past.” She first read “The Onondaga Madonna” as a student—and no attempt was made to contextualize the poem. “Scott was pictured by my professor as someone in favour of Indigenous rights. That was deeply insulting.” Rak insists that “Canada is a neo-colonial entity—it’s not over, we’re not postcolonial. So it’s important to teach these figures.”

Cindy Blackstock agrees. She simply wants more attention paid to those who spoke out against Duncan Campbell Scott in his own era. A few people defied his power and dissented from his beliefs—notably Peter Bryce, chief medical officer of the Department of Indian Affairs, who, in 1907, wrote a scathing report on the terrible conditions in residential schools, later published as The Story of a National Crime. Bryce dared to confront established power; he sensed that revolt was essential to progress.

“The narrative that should always be heard,” Blackstock suggests, “is Bryce and Scott in conversation. I believe Scott’s poetic contributions are far outweighed by his work for Indian Affairs. But he was a person of national significance.” We don’t need to forget Duncan Campbell Scott, she says. “We need to decide how to teach him.”