Dianna Hu spoke at TD presents The Walrus Talks at Home: Inclusion (Part 1), which took place on October 27th.

You can watch all The Walrus Talks speakers from this event here: The Walrus Talks at Home Inclusion

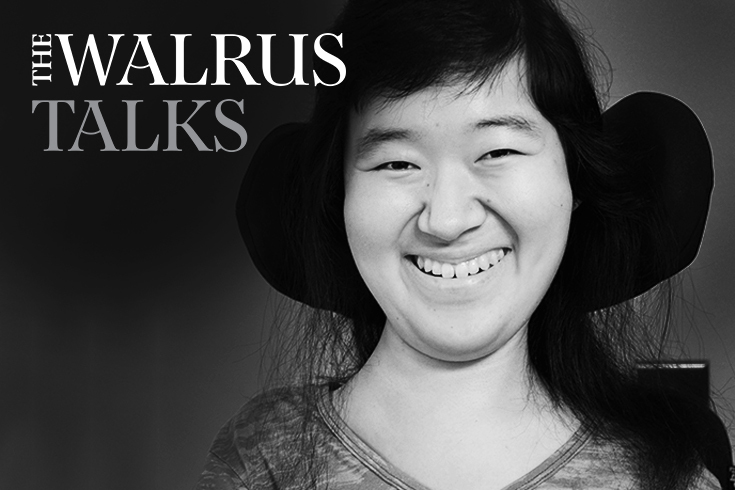

My name is Dianna Hu and I’m a software engineer at Google. I’m wearing a black T-shirt with the emblazoned words, “30th Anniversary of the ADA 2020: Equity, Diversity, Inclusion” to commemorate 30 years of the Americans with Disabilities Act in the United States. I am sitting atop my motorized wheelchair, a Permobil. I’ve been driving wheelchairs since I was two years old. I was born with Spinal Muscular Atrophy, SMA for short.

SMA is a neurodegenerative disability that severely weakens the muscles, making it difficult to perform many basic activities of daily living. Walking, sitting, even breathing become challenges for someone with SMA. It’s been called the top genetic killer of infants. When I was diagnosed at 18 months, the doctors told my parents they weren’t sure whether I’d make it to my next birthday.

From the start, my life has been a struggle for survival. And that struggle for survival has strengthened me. It has hurled obstacle after obstacle in my path, and it has unlocked the resiliency to confront them. There’s a theory about confronting the challenges of life with a disability. It’s called spoon theory. The disabled person starts out each day with a small, finite set of spoons—units of energy—to spend on tasks they need to carry out during the day. Once you’re out of spoons, you’re out of luck.

Here’s what my day of spoons looks like: I almost always wake up exhausted, because I need to be turned multiple times every night to avoid bedsores. Just getting out of bed and ready for the day, that’s a spoon gone. Then I wait for the shuttle to take me to work. It usually has a ramp, but that ramp is sometimes broken without warning, or the bus is too crowded for a wheelchair even though it can somehow fit the five able-bodied people who were waiting next to me. Waiting for the next shuttle, realizing I’ll be late for my meeting, that’s another spoon gone. Then trying to get to my meeting, navigating a series of elevators with buttons that are too high for someone in a wheelchair to reach, the time spent grappling with the limits and the irony of an elevator inaccessible to a wheelchair user, that costs at least another spoon. And on, and on, and on. It’s not even lunch time yet, and more than half my spoons are gone. These are the sacrifices that a person with a disability must make every single day just to get through the day. The physical world is a spoon sucker.

But that state of the world is changing. The pandemic has forced the world at large under quarantine, and work in many areas—including Google—has gone remote. Work from home. And there is no environment more optimized for my accessibility needs than home. I love it.

Now I have the freedom to wake up each morning a little bit later, with a little less sleep deprivation and a little more energy to face the day ahead. I’ll take that spoon back. I also don’t have to grapple with the uncertainty and stresses of transportation, another spoon for me. And not to mention eating, and drinking my favourite cups of tea throughout the whole day. I no longer have to intentionally dehydrate myself to avoid the far too few accessible bathrooms wherever I’m going. I can drink when I want to drink! The flexibility of working from home has let me take back my freedom one spoon at a time.

With more spoons, I can do more. My boosted energy throughout the day translates to boosted productivity. I can attend more meetings and events without the anxiety of planning accessible routes and contingency plans for inevitable failures in the physical world. I can focus on managing my code more than my spoons. I have the physical and mental bandwidth to dedicate myself to accessibility passion projects, both in and out of work. This kind of freedom and flexibility of working from home has been a longstanding accommodations request from the disability community. And now it’s revolutionizing the world at large.

I’m incredibly fortunate to have a manager who will support a continued work-from-home accommodation for me, even after the chaos of the pandemic subsides and the world returns to “normal.” He is looking out for my well-being, and he recognizes that optimizing for my well-being is also optimizing for my ability to contribute to my company. This is a satisfying win-win for all parties involved. I urge employers, event organizers, everyone who has a say in crafting the way we interact with the world around us: let the new “normal” continue to include this virtual, equalizing agent of accessibility, this ultimate spoon redeemer.