Fame is not new to Margaret Atwood—it’s a by-product of life as a perennially prizewinning, bestselling author. But in September, The Testaments, her long-awaited sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale, was released, and she became something else entirely: a worldwide cultural phenomenon. The novel, set in a not-so-distant United States where fundamentalist fascists have gained power and stripped away women’s rights, sold more than 300,000 copies across the US, the UK, and Canada within the first two weeks alone. Atwood appeared on cover after cover leading up to the launch—Time, The Sunday Times Style—and her release-day interview, onstage at London’s National Theatre, was broadcast to 1,000 cinemas around the world. Before The Testaments hit stores, it had already been nominated for both the Giller and Booker prizes (it made the longlist for the former and would go on to win the latter), and a television show—building on the wildly popular series The Handmaid’s Tale—had been announced.

It’s remarkable that Atwood, who turned eighty in November, has reached this crest after spending six decades writing into an ever-shifting cultural landscape. When she was starting out, writers, for the most part, didn’t get published in Canada. Canadian literature as a concept didn’t even exist. To understand how Atwood grew into the literary celebrity she is today, we reached out to some of the writers, publishers, and friends who know her, and her words, best.

Charles Pachter is an award-winning contemporary artist whose work has been exhibited in the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Royal Ontario Museum, and across Europe and Asia.

Adrienne Clarkson served as the Governor General of Canada from 1999 to 2005 and was a long-time broadcaster with the CBC.

Rosemary Sullivan is the author of fourteen books, including The Red Shoes: Margaret Atwood Starting Out and Stalin’s Daughter.

Adrienne Clarkson: I think she was already publishing in all kinds of little magazines—everybody got published in little magazines then. What I remember from that first day is that she read a poem. I don’t remember what poem it was, but she read it in her inimitable voice. It was a true poem.

Charles Pachter: We were constantly writing to each other. So many letters—over 300. These were the days of those little Olivetti typewriters. She was interested in me as an artist, and whatever misgivings I had, whatever was on my mind, I would write to her because she always had an answer. I remember when a high-school teacher gave me a D-minus in art, and she said, “Never mind, someday you’ll be writing God’s murals in the sky and she’ll be roasting in hell.”

Adrienne Clarkson: None of us, at that time, aspired to the heady heights of being world-famous writers. We thought that if we just got our writing down and somebody could publish it, that would be enough.

In those early days, Atwood set her mind to poetry. In 1961, while still a student, she published her first collection, Double Persephone. Only 220 copies were made. Three years later, she released The Circle Game. The volume began as a collaboration with Charles Pachter, who created fifteen handmade books as part of a university assignment. When it received a wider release, in 1966, it won her the Governor General’s Literary Award. Atwood was twenty-seven at the time, making her the youngest winner in the prize’s history.

Eleanor Wachtel is a writer, broadcaster, and host of the CBC’s Writers & Company.

Adrienne Clarkson: I always love it when she puts out a volume of poems. It’s as if something just happened.

Charles Pachter: I truly believe that her poetry will be her most enduring legacy. I’ve read through her more dystopian novels, but I don’t remember them the way I remember the poetry. When she sent me the manuscript for The Journals of Susanna Moodie, I was so floored by its beauty. She’d read the original Susanna Moodie book, Roughing It in the Bush, which is a quite florid, very Jane Austen–like account of a nineteenth-century British settler in Upper Canada, and she condensed each chapter into a poem. For example, her describing the cholera epidemic:

After we had crossed the long illness

that was the ocean, we sailed up-river

On the first island

the immigrants threw off their clothes

and danced like sandflies

We left behind one by one

the cities rotting with cholera,

one by one our civilized

distinctions

and entered a large darkness.

Eleanor Wachtel: Some people argue that they like her poetry more than her fiction, but you don’t have to choose. You can have it all.

Between finishing graduate school at Harvard and teaching in Montreal and Vancouver, Atwood worked on her first novel. The Edible Woman, released in 1969, tells the story of Marian, a young woman, newly engaged, who gradually loses her ability to eat. The book satirizes the consumerism and stifling gender roles of the sixties, anticipating the feminist movement that grew in the following decade. This kind of cultural foresight would continue throughout Atwood’s work. Three years later, she published Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature. It was one of the first attempts to categorize the country’s nascent literary scene, and it set Canadian writing apart from that of the rest of the world. Survival soon became a staple in English-literature courses across the country.

Sarah MacLachlan is the president and publisher of House of Anansi Press.

Donna Bailey Nurse is the author of What’s a Black Critic to Do? and the editor of Revival: An Anthology of Black Canadian Writing.

Esi Edugyan is a two-time winner of the Giller Prize, for her novels Half-Blood Blues and Washington Black.

Donna Bailey Nurse: At that time, she got a lot of flak for it, I think partly because she’s an ideas person and there were a lot of men who resented that: they were resisting everything she had to say.

Rosemary Sullivan: I’m a product of the sixties as well, and you have to remember, we were told that all genius in the arts was male, that the role of the woman was as the handmaid to the artist. It used to be you’d set a novel in Paris because who knew Toronto; you had a male protagonist because who wanted a female protagonist. If you were a woman, you’d disguise your name as P. D. James or something. You didn’t expect to have a career as a woman writer. Then, suddenly, all these writers came along: Margaret Atwood, Margaret Laurence, Alice Munro. One became a Nobel Prize winner, and Atwood has had a cultural success that’s been matched by only one other woman writer, the author of the Harry Potter series.

Eleanor Wachtel: She became extraordinarily well known in media circles in Canada—not just literary ones but as a phenomenon in the second-wave feminism of the early seventies. Power Politics came out in 1973, which I still quote: “You fit into me / like a hook into an eye / a fish hook / an open eye.”

Charles Pachter: She had what I would call positive ambition. Despite what many people saw as her shyness and awkwardness with people, she became more polished in front of the camera. She became a media star and seemed to relish it.

Eleanor Wachtel: She did tons and tons of media, especially television. My pet theory is that it affected how she did subsequent interviews. Because she was interviewed by so many people who hadn’t actually read anything she’d written, she was not exactly more guarded, but she knew what she wanted to say and would say it.

Atwood’s exposure continued to grow with each book, winning her admirers and detractors. In 1979, William French, writing in the Globe and Mail, said, “There’s a strong feeling at the end of Life Before Man that after four novels, she still hasn’t reached her potential.” His critique would prove prescient. Six years later, she released The Handmaid’s Tale and introduced readers to the theocratic state of Gilead, where reproductive slavery is rampant, public executions are the norm, and state surveillance is a constant threat. It became her most acclaimed book yet.

Rosemary Sullivan: I think Margaret Atwood has her finger on the cultural pulse, and she’s usually six months ahead of the rest of us. Before breast cancer became a plague that everybody was talking about in the eighties, she was writing a novel about it—Bodily Harm. Then she was living out behind the Berlin Wall, when East and West Germany were still divided, and began to think of America and its Puritan history and wanted to write a dystopia.

George Saunders is the author of the Booker Prize–winning novel Lincoln in the Bardo and four short-story collections, including the New York Times Best Seller Tenth of December.

Adrienne Clarkson: When The Handmaid’s Tale came out, I think a lot of people felt that it was a diversion for her. I found it deeply, deeply disturbing, and I remember thinking, “Why has she done this?” And now we know—what is it, thirty, thirty-five years later—that she understood there was something going on underground. It’s like people looking at a body, looking at you, and thinking, “That’s you.” She looks at the nerves underneath and the veins and the arteries.

Michele Landsberg is a feminist activist who has written columns for the Globe and Mail, Chatelaine, and the Toronto Star.

Esi Edugyan: Coming to Atwood, you understood this was serious literature, but it was also something that spoke to you. I hesitate to use the word “accessible” because I don’t mean to downgrade her work, but it certainly was something I could easily understand and even connect with as a teenager.

Rosemary Sullivan: You don’t feel the sky is falling until it falls on you, right? We’re in a moment where it feels like the sky is falling. Things are happening now—children being separated from their parents, being held at the American border—that are just unacceptable, yet there’s no way we can figure out how to react cohesively to stop them. You feel that this wave is taking over—of suspicion, of white supremacy, of racism—and this idea that we’re somehow at risk. Atwood doesn’t just listen to that, she actually writes about it and finds a way to warn us about it. She writes The Handmaid’s Tale in ’85; it takes over thirty years for the world to catch up with it. But how bizarre and how tragic that we seem to be catching up with it now. Most of us who were feminists—Atwood would accept being a feminist but only in a particular sense—thought, “Okay, we won something.” We now stand here looking at the misogyny of the world—you’ve got Putin, you’ve got Trump, all these misogynistic leaders in power, and you’ve got to say, “How did that happen?” The Handmaid’s Tale is as current as it needs to be now.

Adrienne Clarkson: We studied E. M. Forster in our fourth year—Howards End and A Passage to India. Forster said two things. One, at the front of Howards End, was, “Only connect.” The other was that a true novel is prophetic. By that, he didn’t just mean that it would tell the truth about the future. What he meant was that there was the nature of prophecy in it. That’s what we have with Margaret Atwood’s work.

Sarah MacLachlan: She leads, you follow. When she was asked to be a Massey lecturer and she agreed, we thought her subject would be literary criticism. Then she told us it was going to be about debt. We all thought, “Oh, you’ve got to be kidding. What do you know about that?” It turns out that, when we published it as a book, Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth, in 2008, it was the beginning of the economic crisis, the meltdown on Wall Street. It was an instant bestseller. She’s got an idea, you just go with her. She is a bit clairvoyant.

Thomas King is the author of The Inconvenient Indian and The Back of the Turtle, which won the 2014 Governor General’s Award for Literature.

Over the following decades, Atwood released a steady stream of novels. Cat’s Eye explored the cruelties of adolescent friendships; The Blind Assassin, an intricate mystery about the fraught relationship between two sisters, won her the Booker Prize. After sixty years as a popular thinker, writer, and speaker, working across genres and formats, a mythology has grown around Atwood. She has been described as a trickster, a man hater, an oracle.

George Saunders: I knew she was at the Salisbury Literary Festival, and I was kind of nervous about meeting her, as a person tends to be. Then I found out that we were supposed to travel to another event together in a bus. And then I found out that the bus was just Margaret and her partner and me. And then I found out that I was hungover. And, I think, a little jet-lagged. I was really not feeling well. So I got situated in the front seat of this van, next to the driver, and Margaret and Graeme were in the back. My mission was twofold. One: don’t engage. And two: don’t throw up. Those were my high-minded aspirations. And so I was sitting there, really feeling terrible, and the driver figured it out and had a bit of a mean streak, so he was kind of speeding and swerving and looking over at me kind of slyly. I was bearing down and trying not to disgrace myself. At some point, I felt this little tap on my shoulder, and I’m thinking, “Oh no, Margaret’s going to yell at me for being hungover at a literary event.” But she handed up this little pill, and I was in such a sorry state that I just took it. I thought, “That’s Margaret Atwood. She wouldn’t poison me. She wouldn’t drug me—with anything too powerful.” So I ate it. It was some kind of homeopathic hangover remedy, but it was a sequence of pills that made up this remedy.

Charles Pachter: I know she takes a lot of vitamins—I’ve seen her scarf down about twelve or fifteen vitamins a day. [Atwood later clarified that she takes closer to ten a day and that some of them are minerals.]

George Saunders: I just kept taking them, and every so often she would lean up and whisper, “Just focus your eyes on the horizon”—almost like philosophical advice. And it worked!

Eleanor Wachtel: She’s what my high-school teacher would call a “good citizen.” She engages with the community and the world. Whether it’s street life in Toronto or the CBC lockout in 2005 or—on a whole other scale—environmental disaster.

Michele Landsberg: I once was asked to write a feature about her, I think it was for Chatelaine. She and Graeme were on a farm in the country, and I remember how delighted she was to show me around the things she was growing and talk about birds.

Jonathan Franzen is the author of ten books, including Purity, Freedom, and The Corrections.

Adrienne Clarkson: She and her partner, Graeme Gibson, helped form The Writers’ Union of Canada in 1973. Then, they breathed life into the moribund Canadian branch of PEN, the oldest civil-society organization dealing with human rights in the world.

Eleanor Wachtel: Atwood is out there. When there’s an event to celebrate another writer, she’s there. If there’s a benefit for a noble cause, she’s there. She shows up, she writes articles. And the thing is, for someone with her kind of career, she doesn’t have to. She’s already won all the prizes available, more or less, in Canada.

Adrienne Clarkson: The Giller, the Governor General’s, the Commonwealth, the Trillium—and on and on.

Thomas King: I think she’s gone out of her way for Native writers. She’s not a rah-rah, wave-the-flag advocate, but she does it as part of her social conscience. With me, for instance: I got to Canada in 1980. I was out in the Prairies, Lethbridge, and I didn’t know her, she didn’t know me. I published a couple of short stories—this was very early on in my career—and she, out of the blue, wrote an article on them. I was sort of like, you know, “Oh boy!” It gave me a boost in my writing career that I hadn’t expected to get. You can’t get any better than that, having a major Canadian writer write a very nice article about your work.

Eleanor Wachtel: She says she does it because her character was ruined by the Brownies and the Girl Guides, and that she still has difficulty resisting “lend a hand” appeals. She can recite the Brownie Promise if you ask her to.

Sarah MacLachlan: When we were on the road for the Massey Lectures, we used to go into the hall to do a sound check, and she would sing camp songs. Like, “They built the ship Titanic, to sail the ocean blue . . . ” So she and I, we’d sing. People thought we were a little bit nuts.

Karma Waltonen is a lecturer at the University of California, Davis and the president of the Margaret Atwood Society.

The release of The Testaments marks seventeen novels, seventeen volumes of poetry, ten books of nonfiction, eight short-story collections, eight children’s books, and one graphic novel for Atwood. She’s still writing today. In a recent interview, she didn’t rule out returning to Gilead for another story.

Sarah MacLachlan: I mean, this is Harry Potter territory, right? As I look at the sales numbers, it’s something. It’s something.

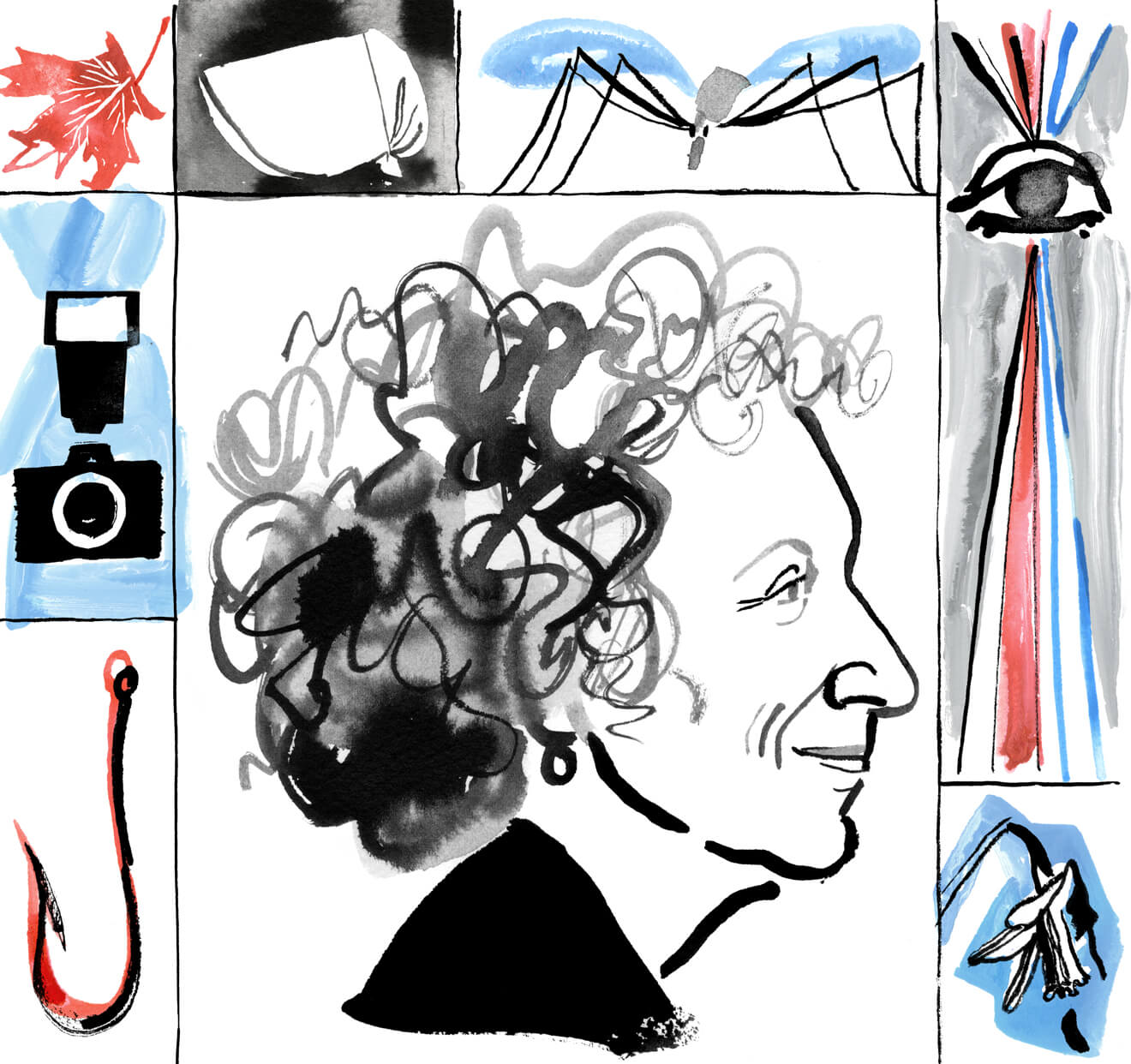

Thomas King: In many ways, she’s much bigger than life. If you tried to create her character in fiction, you wouldn’t be able to. Did you see those pictures in the Times that Tim Walker took of her? The ones with all the hair like Bride of Frankenstein? I said to myself, “Only Peggy would do something like that.”

Heather O’Neill is the bestselling author of The Lonely Hearts Hotel, Lullabies for Little Criminals, and The Girl Who Was Saturday Night.

George Saunders: It’s a real privilege to be on a stage with her. It’s a little scary because she’s so smart and she has such a low threshold for bullshit. You have to aspire to be like she is, which is 100 percent alert. I don’t think she likes boredom, and she doesn’t like phoning things in. You see that little ornery look in her eyes and it’s like, “Uh oh, this moment will not be allowed to be dull.” Most of us, I think, live another way, which is to say, “Please, God, help today be a succession of dull moments, moments when I don’t shake anything up or risk making a fool of myself or risk making somebody uncomfortable.” But, I think, with a few great ones in the world, they feel life so acutely that it offends them to allow a dull moment. My hunch is that she recognizes stasis and boredom and the status quo as enemies of intelligence.

Rosemary Sullivan: Margaret Atwood has always said, “I don’t want to be a role model.” Because what she’s doing is not giving you prescriptions for living. That’s really not, in her mind, her assigned role. Her assigned role is to be a writer.

Heather O’Neill: I think that she’s such an incredible reader. She just reads everything, and you can feel the intertextual influences in her work. You realize how important reading is to writing and also how important reading is to having a good life. Why is she so alive? Because she reads constantly and has all these ideas bubbling in her head.

Rosemary Sullivan: When she’s asked if it’s time for the Nobel Prize, she says, “I don’t want it because everybody who gets the Nobel Prize never writes another book.”

Thomas King: If they were going to give the Nobel Prize to another Canadian writer, it certainly should go to her.

Esi Edugyan: I was in California, being interviewed onstage, and I was talking about how, when I was in graduate school, I asked my fellow students if they could name ten Canadian writers, period, in any genre. Many of them couldn’t. So, onstage, I said, “Of course, everyone knows this particular set of writers now,” and I mentioned Atwood. And then I was interrupted by the interviewer, who said, “Well, she’s a world writer.”

George Saunders: Tolstoy says a real artist is someone who genuinely insists on getting themselves lost in the process and insists that the search be for something really big. I think that’s what she’s done. It feels to me that with each new project, she’s a little kid again. She’s an eighteen-year-old aspiring writer who’s like, “Wow, writing! What can you do?” Every time you get done, you start over. That takes a real spiritual capaciousness, but if you can do it, that’s a guarantee of a long career.

Rosemary Sullivan: I’m quite nervous—about climate degradation, about totalitarianism. In 100 years, there’s two options: either her books will be burned or they will be seen as extraordinary explanations of what happened at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Charles Pachter: I want to see what she’s going to do when she’s 100.

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.