Early in the morning on a dark Sunday in September, gunfire echoes over a secluded range in rural Alberta. Rob Furlong, one of the world’s most gifted snipers, paces behind a line of shooters. His hulking frame is covered in desert camouflage marked with his corporate logo—crosshairs over a maple leaf. His face is tanned from a recent training mission in Iraq. He divides his focus among a collection of psychiatrists, dentists, builders, teachers, and oil riggers who’ve each paid $1,500 to learn the art of the long shot.

I’m one of his eighteen students. He stops above my station and peers at my target—a hole in a cut-out of a deer set up 600 metres away. I’m sprawled on my stomach with a rifle scope at my eye, and in this way have come to glimpse the world through the crosshairs that have defined my instructor’s life. I pull the trigger and wait for Furlong to tell me whether I’ve hit my target. But he says nothing. I inhale the scent of burned gunpowder, lift the stock from my bruised shoulder, and begin running through the list of potential causes for this latest miss.

Furlong taps me on the foot and tells me to hand over my weapon.

He takes my place on the shooting line, peers through my scope, and senses what I can’t: a wind cutting through the rain. The gust is from the east, forceful enough to alter the trajectory of the bullet he’s about to bury into a hole the size of a tuna can—too far for the naked eye to see. He eases the stock deeper into his shoulder, raising the crosshairs until they hover just to the right of the target.

Then he stops moving. There’s a manufactured tranquility as he steadies his limbs and core for the recoil. His body flattens into the earth. His finger rests on the trigger. His lungs fill then empty. Fill, empty, then fill again. He exhales half his breath then holds onto the rest—the ideal amount of air to prevent shaking. He gives the final signal.

“Stand by,” he tells me.

I focus on his target using a binocular-like device, then utter the words he’s taught us, confirming permission to fire.

“Send it,” I say.

A twenty-millimetre-long projectile rips through the sky at 2,500 kilometres per hour. The sound of the explosion penetrates my ear plugs.

The sniper reloads quickly. His finger never leaves the trigger. The spent cartridge from his last shot tumbles to the ground. He rams the bolt forward, sliding another bullet into the chamber. His chest rises then falls, rises halfway again, and then:

“Stand by,” he says.

“Send it.”

He threads another bullet into the hole. He adjusts the scope on my weapon and resumes his place behind the firing line of Rob Furlong’s Marksmanship Academy.

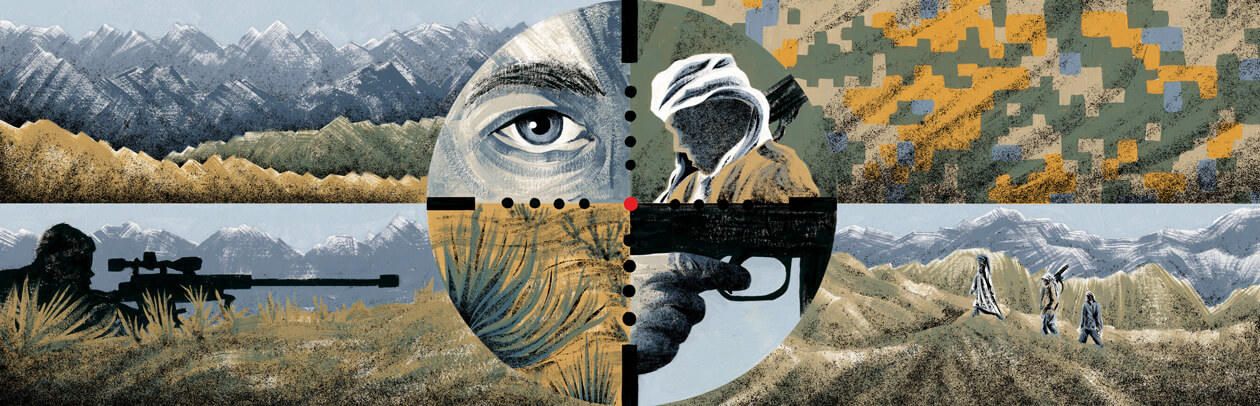

The first rule here is that no one calls it “sniper school.” At this shooting range, Furlong helps pre-screened gun owners become better marksmen. He also runs a sniper school, but it has a different purpose: training police and soldiers from the deserts of Iraq to the jungles of South America how to hunt humans. The distinction between “marksman” and “sniper” is important to Furlong, who, fifteen years ago, killed a man from 2,430 metres away—the length of about thirty typical city blocks. It was the longest confirmed kill shot known to military history.

For a while, that achievement made Furlong the pride of the Canadian Forces. Now, at forty-one, he’s a largely forgotten man. In 2002, he and five other snipers from the third battalion of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry supported a mission to destroy Al Qaeda and the Taliban. Among the first Canadians to see combat in Afghanistan, the Newfoundlander killed more insurgents in nine days than either he or his country has ever been comfortable admitting.

He’s hardly spoken about any of it in years—the code of anonymity that governs the sniper class can be hard to break. (Of the two soldiers present for Furlong’s kill shot, one could not be reached; the other declined to comment for our story.) But Furlong embodies the legacy of what he and the rest of the Canadian Forces accomplished during their tour—whether or not anyone cares to celebrate it. “Every soldier that went in there proved that we are a world class military,” he says. “We lost a lot of guys, but we killed a lot, too. Canadians don’t like that, because it’s dirty.”

After doing what he was trained and ordered to do, Furlong came home to a different kind of fight. It isn’t easy, he learned, being a war hero from a country that doesn’t like war.

Furlong’s earliest memories include waves crashing against the rocks across the road from his family’s tan-coloured house. He could smell the sea from his bedroom. The eldest of six children, Furlong grew up in Joe Batt’s Arm, an outport on the north shore of Fogo Island where, for generations, his family had been fishermen and sea captains.

He doesn’t remember the first gun he ever saw, though he suspects it was one of the many his grandfather kept stashed behind the stove. He does remember the first gun he fired: an air rifle with a plastic stock and iron sights that was good enough to pick off a fly on a rotting trout from three metres away. He was around nine when he got that weapon. He liked school, but dreamed only of the bell. When it rang, he would grab his brother, join his friends, and head for the hills that rolled from the sea. There, he’d drop to his stomach and wait for shorebirds to enter his sights. He bagged his first partridge before he downed his first beer.

High school came and went. Restless, he headed to St. John’s to spend his nights working security on the big docks. When friends fled for the mainland, he felt trapped. It was the mid-’90s and the cod stocks had collapsed. When he wasn’t patrolling the waterfront, Furlong went out running or sat in the apartment he shared with his brother, asking himself if this was all there was to life.

He was twenty-one and driving home from a night shift one morning when he spotted a Navy officer in whites placing a sandwich board on the sidewalk outside a recruitment office. Furlong stopped his car, went inside, and was taken to a room full of VHS tapes. Videos of soldiers on frigates or standing next to howitzers didn’t appeal. Then he pulled out a cassette marked “infantry.” Soon he was watching guys jumping from the bellies of Hercules transports. He’d never been on a plane. Furlong shipped off for basic training two and a half months later.

“My parents understood my decision,” he says. “They knew I was lost. As a country, we weren’t engaged in war, so they weren’t that concerned.”

The hangover from the 1993 Somalia Affair—in which members of the elite Canadian Airborne Regiment had tortured and murdered a Somali teen during a peacekeeping mission—had left the military demoralized. It had been nearly fifty years since the country had gone to war as a full-on combatant.

Furlong began to distinguish himself at basic training, where he was classified as the second-best shooter in his cohort. Then, with the girlfriend he’d met while working in St. John’s, he moved to Canadian Forces Base Edmonton. Under the tutelage of hardened ex-members of the disbanded Airborne Regiment, Furlong joined the third battalion of the Princess Pats, Canada’s rapid-deployment force at the time. In 1999, he was stationed in Bosnia, where NATO was tasked with preserving the ceasefire between Serbs, Croats, and Muslims.

In Bosnia, Furlong shadowed Graham Ragsdale and Arron Perry. Ragsdale had belonged to the Airborne Regiment and was a rising star in the Princess Pats’ sniper cell. Perry was also ex-Airborne and a skilled sniper, though he was known for having an attitude problem. From them he learned that you have to be born a marksman before you can become a sniper. Only soldiers with a natural ability to fire accurately under duress can be trained to understand the effects of barometric pressure, temperature, and humidity on the trajectory of their shots; to calculate the speed of wind rustling through the leaves on a distant tree; and to track and predict human movements.

Together, they engaged in war games against other NATO forces. “The snipers back then were basically like nuclear weapons,” says Furlong, who claims they were rarely used “for the real thing.” As a non-qualified sniper in a mock combat mission targeting others with lasers, he found a perch and neutralized more targets than any other participant.

Back in Canada after his tour, Furlong began accumulating the credentials required to become a fully certified sniper. “The recon course nearly killed me,” he says. “Little food or sleep for five days. Just water and nearly a hundred pounds of gear. It was essential training to operate autonomously behind enemy lines.” At one point, they gave him a potato and a live chicken. He had to kill, pluck, and cook the bird to finish the course.

He also began familiarizing himself with his legendary predecessors. Francis Pegahmagabow, the Ojibwa First World War sniper from Parry Island, Ontario, who killed 378 Germans. Or Carlos Hathcock, the United States marine who, during the Vietnam War, famously shot an enemy sniper through his own rifle scope and also set the record for what was then the longest confirmed kill shot at 2,286 metres (he was known as “The White Feather” because of the feather he wore in his cap to taunt the Viet Cong). More ominous was the story of Tommy Prince, a highly decorated sniper and commando in the Second World War and Korea, who died homeless on the streets of Winnipeg in 1977.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Furlong was packing his bags and preparing for a training exercise he needed to graduate. He walked by the orderly sergeant’s desk just in time to see, on the television, the second plane hit.

Days later, he was in full camo, lying in the dirt outside Wainwright, Alberta, and peering through a scope of a Parker-Hale .308. Fourteen men were on the cusp of becoming snipers. Five passed the course. But there would be no time for graduation ceremonies.

“They told us to report back to our regiment,” Furlong says. “We were going straight to war.”

On October 7, 2001, a US-led coalition began dropping bombs on Taliban targets across Afghanistan. Waves of special forces hit the ground. After Kabul was secured, they moved in on Kandahar. By December, it was believed that Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden had fled to the cave complex of Tora Bora, located in the White Mountains near the Pakistan border. The US launched a campaign of air strikes in early December. Around 200 Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters were reported killed. By January, it had become clear that bin Laden was not in the region.

Back in Edmonton, the Princess Pats were preparing to ship out. “It was an exciting time,” Furlong says. “We were among the first Canadian soldiers chosen to go in.” The day before he left, he took possession of a house with his wife in Edmonton. He had no idea how long he’d be gone.

By the end of the first week of February, roughly 900 Canadian soldiers had deployed to Afghanistan. Their initial task: hold the perimeter around Kandahar Airfield while the Americans and British went looking for the enemy.

“When we arrived, we were wearing green,” says Furlong. “I was told to bring my snowshoes and my arctic sled. I remember walking off the plane and these Americans just staring at us and saying, ‘Who in the fuck are these guys?’”

Members of the sniper cell knew they’d be picked off the moment they saw action if they wore the same green as the rest of the Canadian military. So, before deploying, Furlong says they purchased their own desert camo—old surplus British Army fatigues—that a seamstress in Edmonton then customized by adding corduroy patches over the elbows and knees. The cell set up in a tower outside Kandahar Airfield. Six snipers: the unseen defenders of the Kandahar contingent. But the Taliban and Al Qaeda were nowhere to be seen. They were hiding in the rugged Shah-i-Kot Valley, a high-altitude stronghold protected by caves and snow-capped mountains.

One afternoon in late February, Furlong and the other snipers were told to pack their kit. They flew to Bagram Airfield, in northern Afghanistan, where US Special Forces were preparing for the largest US-led military assault since the Gulf War. “The ramp lowered, and we walked out into a different world,” says Furlong. “SAS, CIA, Delta—a who’s who of Special Forces. We weren’t in the Boy Scouts anymore.”

The six snipers would split into two groups and be dropped by separate choppers into the Shah-i-Kot Valley as part of Operation Anaconda. Each team would carry a McMillan Tac-50, a twenty-six-pound gun that fires bullets two inches long. Team members were assigned different roles: the spotter would line up the kill, the shooter would make the kill, and the guard would protect the other two while they worked. Together, the units would safeguard other divisions and special forces in the area and destroy as many enemy targets as possible.

Tim McMeekin was the ranking officer on Furlong’s team. Furlong was the lead shooter. They’d alternate between spotting and shooting. Perry would man the Tac-50 on the other team, which would be led by Ragsdale as spotter. Dennis Eason covered them as guard.

By morning, Ragsdale, Perry, and Eason were in place. They moved quickly to high ground and started taking down targets from 1,500 metres. But the Chinook helicopter carrying Furlong’s team was forced back to base after it came under fire. Amid the mayhem, hostiles downed another chopper filled with US troops. The valley was quiet by the time Furlong’s team deployed later that day. They ended up landing on lower ground, away from the crash site. That’s when they got their first glimpse of the enemy.

“We saw movement up on a high ridge,” recalls Furlong, who claims they spotted men wearing American fatigues. “We got on the radio and said, ‘We have friendlies in the area.’ Then we heard, ‘Negative, there are no friendlies in the area.’ We were looking at Al Qaeda fighters. They’d just killed the American soldiers in the downed helicopter, and now they were wearing their clothes. They were too far away to engage. But they were watching us come in. We were moving straight into a fishbowl.”

The enemy forces waited until dusk to attack. First came the mortars. Then came the direct fire. According to Furlong, he took cover with his face in the dirt while McMeekin got on the Tac-50 and started lining up shots. Furlong then grabbed the spotting scope. They’d spent months being drilled to take out targets while under threat. But their guard struggled. “The mortars really affected him,” says Furlong. “I remember yelling at him to put his head up, but he wouldn’t. The mortars were landing in front of us and behind. I remember thinking, the next one is going to hit us.”

Under fire, fine motor skills fall away. Simple actions such as pulling back the rifle bolt and reloading become laboured as mind and body are overwhelmed by adrenaline and fear. The closest Furlong had ever come to being shot at was in battle school, when he had live ammo fly above his head so he could hear what a bullet sounds like when it tears past. “The military can’t inoculate you for the real thing,” he says. “When you’re in the moment, you either have the mental stamina to do the job or you don’t.”

The fight carried on until dark. Then the Taliban quieted down. McMeekin and Furlong put on their night-vision scopes and took turns covering Americans from the 101st Airborne and 10th Mountain Divisions, who were operating farther down in the valley.

By morning, an American scout had taken over as guard for the snipers. That day, while the 101st pushed its way along the valley floor, Furlong’s team climbed to a position 2,600 metres up. “It took us a while, but we found where the mortars were coming from,” Furlong says. The mortar operator was his first kill. He says he didn’t feel anything after neutralizing the threat. “It was just my job.”

Furlong watched through his scope as armed fighters moved mortars by donkey through the valley. “We were so effective at killing those guys that they would try to crawl on their hands and faces, but we were so high we could still see them. They had no idea where the bullets were coming from. We shut down their resupply lines. Then we ran out of ammo.”

Furlong refuses to disclose the number of men they killed. Snipers operate with a “one shot, one kill” ambition. It’s a motto often tattooed, along with crosshairs, on their bodies—though not on Furlong’s. But they rarely bring up the subject of casualties, especially when speaking to civilians, who may equate killing with murder. All he’ll say is that he went into battle with 110 rounds of ammunition. When they ran out, the men called in air strikes.

Around the sixth day, they finally received a new supply of American ammo. The new bullets exited the Tac-50 at a higher velocity than the previous set of rounds. Furlong and the snipers had anticipated that the gun would be effective at a distance of up to 1.8 kilometres. Anything beyond that, they thought, and accuracy would be compromised by the effects of gravity, wind, and air resistance. But the snipers’ elevation in the valley allowed them to shoot targets farther away than expected, and the Taliban were pushed farther from their position. Soon the snipers were firing rounds that travelled 2.2 kilometres. Then Furlong took the shot that would make him famous.

“Tim saw them first, three guys walking into the valley floor,” Furlong says. One of them had a machine gun over his shoulder. “We let them come in.”

According to Furlong, McMeekin confirmed the enemy’s distance with his rangefinder—2,430 metres. Furlong made the adjustments to the elevation knob on his scope, raising the crosshairs and the barrel to compensate for the arc of the shot. He prepped his breathing and steadied his finger on the trigger. “Stand by,” he said.

“Send it,” McMeekin replied.

Furlong fired, and about five seconds later, the bullet dusted up in the dirt to the right of the target. Furlong heard McMeekin call out the correction. Furlong reloaded, then fired another.

“I didn’t see where it hit,” says Furlong. “But Tim said, ‘The guy just jolted. I think you hit his backpack.’”

The targets scurried for cover behind a rock. But they were facing the wrong way and remained fully exposed. Furlong reloaded and lined up another shot. The next bullet tore through the target’s torso. Furlong heard McMeekin confirm the kill.

Furlong reloaded, but the two other fighters ran out of range. For three more days, McMeekin and Furlong remained in the valley, telling no one about what they’d accomplished. According to rumours at the time, it was the American guard who let the Americans know what he’d witnessed.

By the ninth day, Bin Laden was believed to have escaped into Pakistan. There was nothing human moving in the valley.

While Furlong and McMeekin waited for their transport back to base, the American commanders began the paperwork to award them Bronze Stars. Back in Bagram, the snipers reconvened with Ragsdale, Perry, and Eason. As they slipped back in with the rest of the Canadian contingent, Furlong showered off a month’s worth of dirt and sweat. But soon after going to sleep, the two teams were ordered back into action. The Canadian battalion, which had mobilized while the snipers were in combat, was headed to the Shah-i-Kot Valley to do “cleanup.” The military called it Operation Harpoon.

Furlong remembers feeling tired as he loaded up his gear once more. “But we were the only snipers they had.”

The bodies of Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters lay rotting in the sun when the snipers returned with their battalion. While the troops flushed out caves, destroyed bunkers, and combed the valley and mountainside for holdouts, Furlong, McMeekin, and a fresh guard attached to their team went back to the high ground. Furlong remembers the smell of the men they’d killed. For five days, they kept watch over the Canadian contingent. But there were no more hostiles in the region. Operation Harpoon wrapped up.

When members of the sniper cell returned to Kandahar, they learned that they were under investigation. Arron Perry had been accused of cutting a finger off a corpse as a souvenir, putting a cigarette in the dead man’s mouth, and posting a sign saying “Fuck Terrorism” to his chest.

Furlong says that he and the rest of the snipers were kept in virtual lockdown at the base while military police, still haunted by the Somalia Affair, looked into the allegations. They seized Perry’s knife for lab testing and interrogated the entire cell. Perry agreed to be shipped home to face a court martial. Ragsdale was stripped of his command. McMeekin, Eason, and Furlong sat waiting for orders while news spread about the investigation.

The incident contributed to a broader sense of unease about the sniper cells. “Even within the Canadian Forces, there was a reticence to glamorize the snipers’ function,” recalls Colonel Pat Stogran, commander of the Afghanistan mission during Furlong’s deployment. He says his superiors were uncomfortable because, politically, Canada still wasn’t fully ready to make the transition from peacekeeper to combatant.

Stogran supported the snipers. But he understood the discomfort in Ottawa. A sniper’s job, he explains, is sometimes seen as more morally suspect than that of a soldier. “Snipers get right up close and personal. With the optics, they can basically see their targets blinking and breathing.”

As the investigation dragged on, Stogran worried for the snipers’ mental health. “We asked them to do things that no human being should be asked to do. I don’t think you’re a rational person if you don’t come back changed.”

In July 2002, Furlong and the rest of the sniper cell left Afghanistan for Guam, where they were given counselling sessions at a US military base. When he was back home on leave, the phone would periodically ring, and Furlong would drag himself to the base to answer questions about the investigation.

The investigators never found the finger or any other evidence that would justify a court martial. But the damage was done. Perry quit the army. The combined stress of the battle and the investigation left Ragsdale unable to function. With the sniper cell falling apart, Furlong set his sights on joining Joint Task Force 2 (JTF2), the Canadian Forces’ elite commando unit. When he told his wife of his plans, she threatened him with divorce. She knew that if he became a commando, he’d be living off a pager and disappear for who knew how long. He removed his name from consideration, received an honourable discharge, and tried to reclaim a civilian life.

By 2004, Furlong had taken a job as a patrol constable with the Edmonton Police Service. It wasn’t easy going from world’s deadliest sniper to beat cop, even if few in the police knew what he was capable of doing with a rifle. He had been unknown to the general public for more than four years, but that changed in 2006, when his name and the full details of his role in Anaconda were discovered by the media (Maclean’s appears to be the first to correctly identify him). The History Channel interviewed Furlong for a staged recreation of the 2,430-metre shot. By September 2007, he was cruising around north Edmonton with a CBC camera crew in his police car.

In November 2009, when a British Army sniper was reported to have broken his record with a 2,474-metre kill shot in Afghanistan, the media reached out again. Furlong didn’t say much at the time, but he now seems relieved. “I’m proud of what we did. But that shot never held any special value to me.”

Though the cameras captured a veteran who seemed to have his life in order, in private he was beginning to struggle. Six months after the birth of his first son in 2006, his marriage to the woman he’d been with ever since his days in St. John’s fell apart. Furlong prefers not to explain why, but acknowledges that he wasn’t truly present in the relationship, even after he’d left the army. He began taking training courses to upgrade his police rank. When he got tired of patrolling the streets at night, he took courses to go undercover. When the G20 summit came to Toronto in 2010, Furlong was there in riot gear. Ultimately, he ended up on the drugs and gangs unit in Edmonton, working on a task force to fight organized crime.

Furlong was also reaching for the bottle a lot. “There was a culture of drinking that permeated the Edmonton Police Service,” he says. “I got caught up in it.”

On September 30, 2011, ten years after he’d travelled to Afghanistan, Furlong went to a riot-troop training course where, during a night of heavy drinking, he clashed with a former army captain with whom he’d had problems in the past: Furlong saw him as a bully. At around 2:30 a.m., Furlong tried to rally a few sleeping officers to join a party in the hallway. When the captain refused to get up, Furlong told him, “You get out of your bed, or I’m going to piss on you.”

“Fuck off, Rob,” came the response.

Then Furlong urinated on the officer’s sleeping bag.

Days later, Furlong was informed that his conduct was being investigated. He apologized for his actions, admitted he had an alcohol problem, and sought treatment. He believed he was still a valuable asset to the force, which he’d grown to love. His superiors saw it differently. Seven months later, he was dismissed from the police force—the presiding officer at his hearing concluding that Furlong’s “actions show[ed] such an astonishing lack of respect for another human being.”

Furlong doesn’t like to talk about his firing. He sees nothing of himself in the presiding officer’s description of him. He says the months that followed were more traumatic than anything he’d experienced in the army. He felt betrayed by the command unit and by the media. He received calls from friends encouraging him to blame what had happened on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Furlong refused. There were no faces haunting him in the night. No shots fired that he wished he could take back—“except the ones that missed,” he says. Going to war had been the pinnacle of his professional existence. He wasn’t going to dishonour himself by blaming that war for what had happened.

“I’ve educated myself quite a bit about PTSD and about what some of the side effects of it are on the brain. Do I think I had PTSD due to operational stress? I don’t.”

Regardless of the underlying causes, Furlong’s life was in shambles. He began to wonder where he’d be if he’d never left the army. Furlong still visited his old battalion regularly. He’d become a legend; his portrait from a cover of Soldier of Fortune hung on a wall of photos. He even contemplated re-enlisting. The Canadian Forces were in the final stages of withdrawal from Afghanistan, and it was unclear where, if anywhere, they’d be deploying next. But he was too notorious to make a run for the Special Forces. All he’d be good for now was becoming a grunt. And at thirty-six, he was getting too old for that.

Furlong says he owes his salvation to the woman who would become his second wife—someone he’d known for years who was friends with one of his sisters. They’d just started a relationship before he was fired. He says if she hadn’t encouraged him to dust off his old scope and gun, he doesn’t know what would have happened to him.

Dressed in camo, Furlong gives no warning before he pulls the trigger. He reloads and fires another bullet—and then another, eliciting awe from his students. He unloads the gun and walks to a table behind the range where he begins cleaning the barrel. “One thing I learned from the Airborne guys is your weapon should always be meticulous and ready,” Furlong says.

He’s more active now than he would be had he re-enlisted in the Canadian Forces, with no war to fight. He hasn’t shot anyone since he left the army. The notoriety that limited his ability to recast himself as a commando also allowed him to set up as a defence contractor. He employs other former snipers now, men who followed him into Afghanistan. It’s lucrative work, escorting VIPs into hostile territory and training allied forces to line up enemy combatants in their sights.

Furlong loads his students’ rifles into the trailer he hauls around Alberta behind his truck. When the guns have been put away, he changes out of his camouflage and rejoins society. He knows better than most how to keep a low profile, blend in with his surroundings.

There’s a reckoning, he says, that veterans face when their actions in war are exposed. It’s why many choose not to speak about them. Maybe that’s the reason he never tattooed the crosshairs on his skin—even if, ultimately, he’s marked by them forever.

This article appeared in the March 2017 issue under the headline “Kill Shot.”