For my Lolo, 1941–2023

Before news of the bankruptcy hit the press, Delta and Dizzi were already on a plane. Their grandfather sat in the row ahead with Dizzi’s Pomeranian, Wilfred. Ever since Delta had heard whispers of the bankruptcy, she had been on a kind of high. Fuelled by adrenaline, sure, but also a keen sense of vengeance that alerted her worst instincts. Dizzi, on the other hand, was asleep. She had left her job at the nursery school the day before without notice, sad to leave the children but moved to action by familial duty. Delta tapped her fingers on the tray table impatiently and leaned over to her grandfather. “Lolo, how are you feeling?”

He barely turned and raised a shaky hand. “Okay.”

Dizzi had been raised by Delta’s mother, Elaine. The girls were cousins by blood but treated each other with the coy annoyance of sisters. They held a resemblance to each other still, and most people found the pair striking. As children, when Elaine worked late shifts at a white-tablecloth restaurant, they’d often stay with their grandfather. Lolo was in the golden hour of his life and brought the girls along to things that gave him a thrill. After school, he’d take them to a rundown boxing gym where they’d all have at it on their respective punching bags. The real boxers would spar, and Lolo and the girls would crunch on peanuts, laughing when a little blood was spilled.

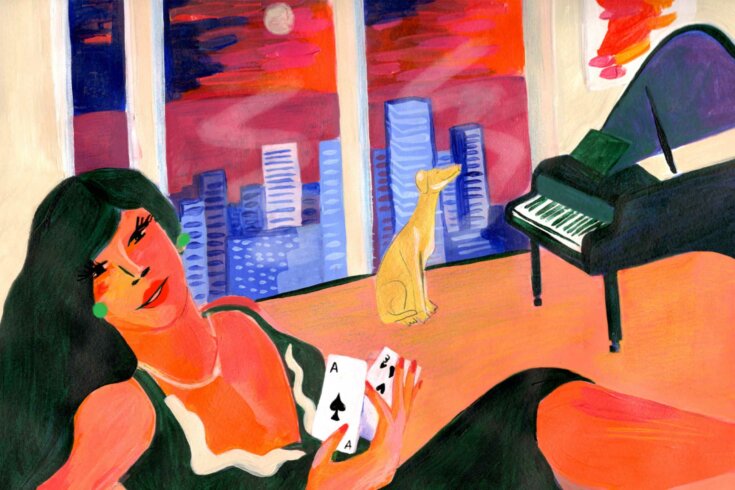

Lolo had been a mathematician in his youth and had a gambling streak. He’d won a humble sum in the eighties and used it as a down payment on their house. You’d think he’d stop trying his luck—after all, who wins the lottery twice? But every night before dinner, they’d all walk to the convenience store and play Lolo’s lottery numbers. Lolo taught the girls card games and eventually, when they were good enough, introduced poker chips. Delta was a natural talent, confident and unreadable. Dizzi played so believably naive that it disarmed most of her opponents. Lolo would later say that the early presence of these skills was the greatest indicator of how the girls would turn out—more than anything like education or astrology.

The plane landed in Miami, and the girls helped Lolo into a wheelchair. A rush of humidity met them on the tarmac. Delta tied a silk scarf over her hair and slipped her sunglasses on; it was not a disguise per se. Dizzi plopped Wilfred on Lolo’s lap as they wheeled him to baggage claim. Delta’s eyes narrowed at the dog. “Why did you have to bring him?”

Dizzi ignored her tone. “Who is going to stay with Lolo when we’re out doing business?”

They checked into the Fontainebleau, right on the beach. After some persuasion, the hotel gave them an ocean view at no extra charge. Delta was good at things like that. She told the concierge that Lolo had never been to Miami and, because of his age, who knew if he’d ever come back. The girls diligently unpacked their things and discussed their strategy for the week ahead. Wilfred sat on Lolo’s lap as they watched the waves from the balcony. Delta pulled on one of Dizzi’s dresses. “We’ll have to shorten some of these a few inches. I can send it down to the hotel tailor if you want.”

Dizzi hit her hand away. “I don’t want to look like we’re out to fish.” The girls had mostly brought a collection of “night-time” clothes for the trip. Beaded dresses, satin skirts, and only the tallest of heels. Daytime would be reserved for strategic planning; some might even have called it scheming.

Parkinson’s had taken over, and Lolo had been on a steady decline for the past few years. His dry humour only showed through in brief episodes, and when it did, the girls would start crying. Some days, he got their names wrong, and others he lived in decades past, still thinking he needed to drive the girls to school. As the first born, Delta was taking it hardest. The thought of him fading away unmoored her, and she was scared for when he would go. She was torn between her life as a playgirl and being around for Lolo’s advancing age. It was Dizzi who’d always been the nurturer, and between balancing all her pursuits, she took on the role of Lolo’s caretaker whenever she could. She wanted Lolo’s time to be as comfortable as possible, even though, day by day, she noticed the sly sparkle in his eyes disappear.

Lolo was a Freemason. For all their lives, the girls did not know what that meant. They grew up with the insignia around the house and thought nothing of it. Last year, the nephew of one of his Masonic brothers had come to Lolo with a proposition. At the time, Delta had been in Paris, working through an exhausting romance with a diplomat, and though she’d made it a habit to check in weekly, calling home often slipped her mind. Dizzi was steadfast about making daily visits to the house, but on the day in question, she’d been stuck in class at the local culinary school. Lolo would never deny a visitor and had invited the nephew in for coffee. It was lonely when the girls weren’t there.

The nephew had spoken of a new kind of currency that was free from the plain rules of stocks and bonds. It lived somewhere in the ether. It was enticing to Lolo, especially when the nephew spoke of high returns on retirement funds. The value went up for no rhyme or reason. Later, the girls found out that the nephew had approached all the aging Masons with this proposition, targeting their wallets like a cold caller. They were at the end of their lives and had an urge to make a last-ditch effort to provide. By the time Dizzi came home with a fresh batch of eclairs, it was too late. Lolo had signed away his life’s savings.

Delta had heard about this kind of investment. She ran in circles with wealthy people who threw cash at anything “innovative.” They wanted to be first. They wanted to laugh and say, “I told you so!” Delta believed that, for many of them, it was a way to simulate romantic feelings that were absent in their personal lives. After all, finance and love are both built on promises and speculation. For them, it was an expensive hobby, and that did not conjure much public sympathy. They would still live cushioned lives after losing millions. Delta was suspicious about anything too good to be true. She believed in keeping her money where she could see it—in her jewellery box. Wherever she went, she carried two gold bars and put them in the hotel safe, for contingency. Dizzi begged Lolo to take the money out of the illusive investment, but he was stubborn, citing the trust he had in the nephew. From what he’d been shown, his returns were on the up and only getting higher.

December in Miami imported all the worst characters. Finance people, art people, people who made a living from being looked at.

All these new schemes to make a quick buck had the bones of an old-world con. The face of the con was always someone who embodied the fashion of the time—a slob, a genius, or finally, a charismatic dum-dum. Now, for this particular exploit, the windfall had been swift for early investors. It made the front pages of all the newspapers. The figurehead was Adam Mercer-King, and after poring over articles about him, Delta determined he was half dum-dum, half slob.

It was December, and Delta was having coffee at Claridge’s with a well-known entrepreneur. It had been months since Lolo’s investment, and she’d almost forgotten about it. The entrepreneur excused himself to take a call, and though he tried to be discreet, his voice rose. It was his financial adviser calling to tell him that he could not cash out assets from a certain venture. Delta had known enough businessmen who went bankrupt, but her ears pricked up when she heard the name Adam Mercer-King.

Delta predicted that it would be a matter of days before the venture imploded. The high rollers would try to withdraw their deposits, with no luck, and it would leak to the press. Once the government’s interest was piqued, the Securities and Exchange Commission would come calling. Delta rang Dizzi from London to say she was on her way home and to pack her bags; they were going to Miami. As she threw clothes into her luggage, Delta yelled, “Why couldn’t he have been defrauded by the air duct cleaning people!”

The nephew who had made the transaction with Lolo had been dealt with—Dizzi was to thank for that. She still hung around the old boxing gym, and the crowd had always been distinctly crooked. Picking Delta up from the airport, she said, “I’ve gained a few cronies, and they’d do anything for me.” Then offhandedly: “Everyone should have a few.”

This was a paltry consolation, though, and the girls wanted to go higher up the chain. They thought of all the grandpas just like Lolo who’d have their savings evaporate. The big-name victims would make print, but what about the everyday people who had taken their chances? Their love for Lolo powered the girls, but so did a strain of guilt. They knew his decision had been made with his love for them in mind. “I want you to be safe,” he’d say. Which just meant secure well past his departure.

Success in wealthier circles depended on being pretty and agreeable. If you really worked it, you could find your way into any room. People found Delta attractive, and she had a sly, back-handed way of seeming docile. From her widespread network, Delta had gotten a tip that AMK (what the press called him) would be in Miami for the art fair, ignoring his upcoming disaster. The girls respected this: to act like nothing is wrong for as long as possible and to live in a dream for just a few moments more. December in Miami imported all the worst characters. Finance people, art people, people who made a living from being looked at. It only made sense to come to a town where the end of the world feels so much closer.

For the first few days, the girls cased the art fairs, talking to dealers and art advisers who loved to brag. They would say, “I can’t tell you who, I can’t tell you how much,” and later, with little persuasion, lean in and whisper names and numbers. On the way to one of the big galleries, the girls ended up sharing a car with a reporter. He was in town to cover the Art Basel party circuit, though his preferred mode of journalism was investigative. Stuck in Miami traffic, he told them stories of Baltic crime lords and corrupt politicians that he had finagled time with.

As he got out of the car, the girls shook his hand. “It’s your lucky day having met us by chance.” They took down his number for future use.

AMK was staying at a suite in the Faena Hotel. The girls heard he had quietly been in talks about the purchase of a few blue-chip pieces, something about “mobile assets.” The few dealers who were in on it knew they’d have to close fast and ship the pieces out of the country. Dizzi had started to bite her nails. “Why waste time on this stuff?” Delta reassured her. “Be patient.”

Lolo, not having stayed away from home in years, fell into a state of confusion and wandered through the halls of the hotel. Each floor was the same, with two elevators on each end of the hallway and towers with names like Chateau and Versailles. He did not remember his room number when hotel staff asked. The staff guided him to the lobby and carried Wilfred in their arms. The girls’ hearts had stopped when they came back to an empty hotel room. They later found him and the dog lying in the sun by the pool. Delta pulled at Lolo’s sleeve. “Please don’t wander, you’ll get lost.” He looked at her blankly, trying to place her face in his memory. Dizzi took a deep breath as her eyes welled, and she scooped Wilfred from Lolo’s grasp. She went straight to the front desk to print out a lanyard with the girls’ phone numbers.

That night, Dizzi and Delta dressed to compete with all the other girls in Miami. Though they could not mimic the high art of synthetic beauty, they put in enough effort to look at the very least expensive. They blew out their hair and mixed tanning drops into their lotion, even consulting a Kevyn Aucoin book on how to contour. Dizzi pulled on her silk dress slowly, careful not to get lotion on it. Delta zipped her up and said, “You waste all this on taking care of kids. Unbelievable.” Delta wore a tight Cavalli dress that had a glittering snake wrapped around the neckline and cabochon earrings that gave her the sheen of a socialite. Her shiny dark hair was flipped out at the ends. The girls helped Lolo put on a suit and slipped his Masonic ring on his pinky. They had dinner plans they could not be late for.

It was one thing to snag a reservation at a Michelin star restaurant but another to have a good table. After slipping the maître d’ a $100 bill, the three of them were sat in the section with the best view. The section was raised a few steps above the other tables, and scanning the room took only a few seconds. The crowd was polished and coiffed, not just for dinner but for the many parties that lay ahead of them. Dinners in Miami were more of a formality, an obligation to sit through out of politeness before you went off into the night. They established a civilized pretense in an otherwise raucous town. The table was the perfect vantage point to be looked at from all angles. And everyone did look. It was sweet to see two beautiful girls with their aging grandfather splitting the côte de boeuf.

Dizzi cut the steak for Lolo into small bite-sized pieces as he tried his best to eat without incident. There were times when he put a fork to his mouth and missed. She patted him on the knee. “You’re doing great.” A man sitting alone at a corner table caught Delta’s eye. He was wearing a baseball hat and glasses. She squinted, having disavowed optical aids. “I can’t tell. Dizzi, you look.”

Dizzi put the wine list up to her face and peered over. “I think so.” She wanted to be sure. As Lolo was mid-bite, Dizzi took him by his arm. “Don’t worry, Lolo, I’ll take you to the washrooms.”

A server came to untuck Lolo’s chair, and confused by the frenzy, Lolo took his cane and got up. “Did I say I needed to go?”

The restaurant was lit by a large chandelier that took up a quarter of the ceiling, filling the room with an orange sultry glow. Diners sat on red velvet chairs and leopard banquettes as the uniformed servers walked a steady stream in and out of the kitchen. Dizzi led Lolo slowly through the restaurant while people glanced over and smiled. “What a nice girl,” they would say or, “I should call my grandparents.” As Dizzi and Lolo neared the corner table, the man in the baseball hat asked his server about dive bars nearby. “Coocoo’s Nest,” the server responded. “It’s where we all go after our shift.”

Dizzi made the swift decision to make contact. She knocked Lolo’s cane out of his hand and paused for effect. As Lolo slowly bent down to reach it, the man in the baseball hat jumped out of his seat to help. “Don’t worry, I got it, I got it.” As he handed Lolo the cane, Dizzi and Adam Mercer-King locked eyes.

She smiled. “Thank you.”

Back at the hotel, the girls tucked Lolo in. Even as Lolo slept, his breathing was heavy and uneven from years of smoking. The girls sat on the counter of the bathroom, freshening up their makeup. It was simple: they would get AMK in a quiet room and have him open up to them. “Is recording someone legal?” Dizzi asked, reapplying lip gloss.

“If only this was New York or Nebraska. Recording someone in private is a felony here. I think if it’s at a bar or club, it’s fair game.” Delta crossed her arms.

“But if he said something bad enough, we wouldn’t have to worry, right? I feel like we’d be in the clear for a little felony like recording him.”

Delta laughed. “By the way, did you notice if he was wearing a watch?”

Coocoo’s Nest was tacky, even by Miami standards. Plastic palm trees were nestled in the bar’s corners, and the floor was gummy with a history of spilled drinks. It was still early, and the only other patrons were at a table in the back. Adam Mercer-King sat at the bar with his hood up. Delta approached slowly and asked the bartender for a dirty martini and glanced over at AMK as though she were doing a double take. “Weren’t you just having dinner at the Robuchon restaurant?”

He barely turned his head to her. “Yeah.” Delta noted that AMK smelled cleaner than she thought he would. His recognizable mop of curls peeked out from under his hood, framing his face. It gave him a cherubic quality, one that had clearly convinced many investors of his pure intentions. He did not have the frenetic energy you might expect from someone who’d allegedly lost $8 billion. Rather, he seemed grumpy, like someone getting over a brief heartbreak.

Dizzi leaned over the bar. “He’s the one that helped me with Lolo.”

AMK arranged himself to face them. Sizing them both up with a grin, he said, “You’re the girls with the grandpa . . . or is that an older patron?”

“Oh! Can you imagine?” The girls giggled, inventing a bashfulness that did not come naturally.

He put their drinks on his tab and ordered a round of shots for them and the bartender. The girls threw their heads back and let the tequila fly past their mouths. AMK asked them what they were doing in Miami. Delta slid back on the bar stool and told him that they’d decided to take their Lolo on vacation after they realized he hadn’t had one in twenty years.

Dizzi put her arm around Delta. “We’re the only ones left who can take care of him.”

AMK tapped his fingers on the bar. “That’s really, really nice.”

“It’s terrible how we treat the elderly. There’re just no proper structures in place.” Delta sighed, taking a sip of her drink. She was being genuine. As children, the girls would walk past a retirement home on their way to school and wave to the people inside. Sometimes they would forget, and they’d run back out of guilt. The people all reminded them of their Lolo, and they would never want their grandpa to feel forgotten.

Dizzi’s face fell. “Sometimes we feel powerless to help . . . ”

Delta interrupted, “ . . . but we do everything we can.”

A karaoke machine sat in a corner of the bar; it took $2 per song. Dizzi tapped AMK on the shoulder with a $20 bill in hand. “Do you have change?”

He was a little looser than when they’d first spoken. A few shots and he’d mellowed; a few more and the girls had the feeling he would teeter into gloom. But for now, he was having a nice time. He took out his wallet and began thumbing bills. He handed them three $100 and a $2 bill each. Dizzi shook her head and tried handing it back.

Delta laughed, snatching the bills out of Dizzi’s hand. “Buckle in, I’m going to sing $604 worth of songs.”

Dizzi, still embarrassed from the exchange of cash, leaned into AMK’s ear. “She really will.”

The bartender kept the drinks coming, and AMK clapped as though Delta needed encouragement. She stood under the one spotlight with the mic in hand, the beaded snake around her neck giving off its own glow. She hadn’t picked “Folsom Prison Blues” with any thought to its significance, but when she sang, “But I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die,” she smiled at AMK. He did not catch on to anything sly in her performance. As she walked back, he handed her a beer. “Amazing! Amazing!”

Showmanship was important in the girls’ family, but it was important to not be too rehearsed. Lolo would tell them the key to success was to make people feel like they’re seeing something they shouldn’t. Leave room for being spontaneous and vulnerable. Being too polished doesn’t get under anyone’s skin. He would hold both their wrists and say, “You want to get inside.” After Delta sang the last notes of “Dream a Little Dream of Me,” AMK took a deep breath.

The hotel room was the penthouse suite with floor-to-ceiling views of Miami. Five bedrooms, a grand piano, and a bathroom the size of the girls’ room at Fontainebleau. A gold statue of a greyhound stood next to the sofa. Dizzi petted its head. “Sweet digs you have here. Who exactly are you?”

AMK opened a bottle of champagne. “A king by name—soon to be dethroned.”

Delta sank into a down-filled sofa and brought out a small plastic bag of mushroom capsules. “Let’s have some fun.” She’d read enough articles about psychedelics and the tech world to know this was enticing to people like AMK.

“I actually have my own I like to take. Nothing too strong. Just a little buzz.” He handed the girls a drink and showed them a bottle of pills labelled “Golden Teacher.” Below, the music from the pool bar was faint to their ears. They could see the crowd disperse into the hotel as the weather became far too unsociable. The palm trees and umbrellas were left to endure the high winds.

Dizzi asked AMK to show her around the suite. He put on some classic rock, marvelling at the surround sound. With a sleight of hand, Delta switched AMK’s pills with the ones she had bought off their hotel valet, who had promised “a highly psychedelic reaction.”

Forty minutes later, they were sprawled across the floor in front of the fireplace. Delta had been doing card tricks for AMK while he’d sat, like a child, completely mystified. “They should hire you here, at the hotel!” His eyes watered. “I admire you girls. You’re both so free, so elegant. I wish I could be as pretty as you. I’m jealous of you.”

Delta gave a bemused smirk to Dizzi. “That’s quite nice, Adam, thank you.” Men had told them this before. Delta had her own theories about the hatred men had for the feminine. Beauty had power, but for men like AMK, power had to come from money . . . and wasn’t that so much uglier? “Tell us more about that story you mentioned, about the big mix-up.”

With her phone set to record, Dizzi sat next to AMK and clapped. “Yes! The big mix-up.”

He let out a pained sigh and dramatically laid down on the shag rug. “It was innocent at first, just moved a few things around to cover the losses. But then it ballooned . . . and I loved the feeling of being loved by everyone, and I wanted to do anything to keep that feeling. I was doing something good for the world. I just thought it would balance out, eventually. We moved everything offshore . . . You girls know I would never do anything bad on purpose, right? Say it. Say it. I’ll give you $10,000 to say it.” It was curious that the mushrooms had given him a desperate edge. His pleading face against the backdrop of this gilded hotel room—and, beyond that, Miami alight—did not help his case.

The girls got up slowly. “Of course not.”

“You’re a good, kind person, Adam,” Delta said, smoothing down her dress.

Dizzi chimed in, patting AMK on the head. “You’ve always just been in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

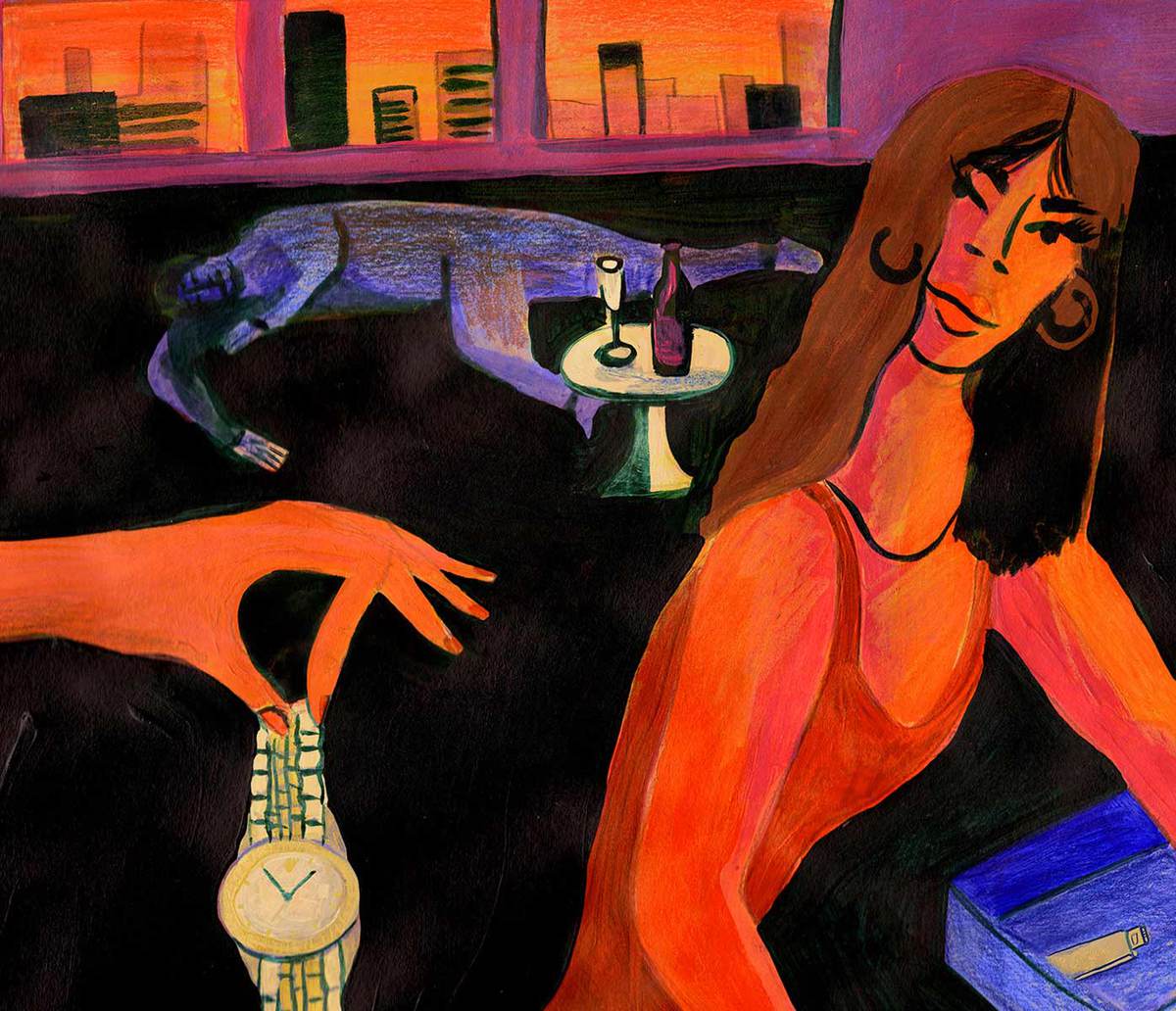

Delta cased the place while Dizzi tucked a sleeping AMK under a blanket on the floor. He looked like a little boy in this light, and it made Dizzi feel guilty. He reminded her of the kids she took care of, the ones who didn’t mean any trouble but had too much imagination to know what trouble was.

“You’re a bad criminal!” Delta said when Dizzi disclosed her misgivings.

“I’m just having second thoughts.”

“Don’t you see? What we’re doing is so much less bad than what’s going on here. At the current scale we’re looking at, I think this is petit larceny, very small. Tiny.”

“I feel like he’s not malicious. We already have him saying all that stuff on tape. Let’s just go.”

Delta ignored her plea, emptying AMK’s suitcases on one of the beds and shaking out all the drawers. “Go watch him.” She did not want to seem cold, but it would be a waste not to finish the job. Dizzi was always sensitive growing up, and that was to be respected and kept untarnished. Anyway, Delta was fine handling the dirty stuff alone.

Behind a few hard drives, she finally found a small grey safe at the back of a closet that could only be opened by a fob. She looked in all the pockets of the hanging jackets and pants and yelled from down the hall, “Check anywhere on him for keys!”

In order to reorient herself to their plan, Dizzi scrolled through the search results for AMK’s name. She gnawed on her manicured nails as words like “fraud,” “Ponzi,” “financial sociopath” flashed onscreen. A beeping sound could be heard coming from the bedroom. They’d found the key fob but not before Delta had made a dent in the safe by throwing it across the room. Amongst passports for different countries and more hard drives, a compact jewellery box sat on the bottom shelf of the safe. The beeping was coming from a diamond tester that Delta was wielding like a bona fide jeweller.

“Taking all the watches would be too much,” Dizzi reasoned. There were six, all rare and highly resalable, probably totalling a cool one-point-five.

“Okay . . . but if we only take three, it makes it even more obvious that three are missing.” Delta took a loupe to the Rolex and turned to Dizzi. “What one is he wearing right now?”

Leaving AMK’s hotel room, they slipped the watches on so as not to arouse any suspicion. A Patek 2499, a Cartier Crash, and a Rolex. Delta looked down at her wrist, watching the diamonds catch the streetlights.

It was three in the morning, and their new reporter friend was at a party on the beach. Things were winding down, and he’d told them not to come. Delta said, “We don’t want to go to your dumb party!” and asked him to meet them outside.

The taxi idled on the corner. They watched the reporter walk up from the beach in his white shirt and thick-rimmed glasses. Rolling down the window, Dizzi handed him a USB stick with their recording.

Delta called out to him, “Do something with that, will you?”

“You girls are strange, wonderful, heaven sent. I’m in love with you!” He blew them a kiss as they drove away.

Delta sat on the porch with Lolo in the family house they’d finally paid off. Wilfred was rolling around in the grass out front. It was one of the first true days of summer. Lolo leaned back in his chair as Delta flipped through the pages of a family album. Dizzi came outside with some lemonade and collected that day’s newspaper from the mailbox. AMK was on the cover with a headline that said, “FRAUDSTER,” and a caption: “Incriminating evidence uncovered by the Washington Post seals the deal at trial.” Without a second thought, she folded the paper under her arm, walked around the house, and threw it in the recycling.

The three of them sat quietly, flipping through old photos as the birds in the neighbouring bush chirped in harmony. Delta stopped at a photo of her and Dizzi as children. She asked him gently, “Now, who’s this, Lolo?”

He was silent and traced the girls’ faces with his finger. A minute passed before he said, “I . . . don’t know.”

The author would like to acknowledge funding support from the Ontario Arts Council and the Government of Ontario.