On Christmas eve, Jude drove to his brother’s house. The sun hung low. He pulled up and parked. Everything looked the same as the year before—the rows of brick, a tree with lights, an inflatable Santa. Nothing was.

Gabe’s wife, Linda, had promised to keep it light. She called Jude inside, gave him a hug, and started laying out food on a tablecloth: a salad, a quiche, bacon, a bowl of chopped fruit, and an assortment of crackers and cheese. She was small and contained, a delicate person, but the clasp on her velvet jacket broke open when she bellowed up the stairs. “Boys, he’s here!”

Josh, who was sixteen, and Ben, two years younger, took their places across the table from Jude. They were glad to see their uncle but unsure of what to say. They both looked down, shoulders curved over their chests and hands twisting in laps. Under the table, Ben’s knee started bouncing. It sent a tremor through the cutlery.

Josh decided to make the first move. He cleared his throat, looked across the table, and said, “Hi Uncle Jude.” Jude smiled back and gave him a little wave. “Hi.” Gabe and Linda joined them. With some relief, they all started to eat.

The boys grabbed at food. Linda reminded them to pass, and Ben used his Yoda voice. “The bacon passing, it is please.” His voice sounded like a recording of his cousin, but Linda pretended not to notice. She kept directing the platter traffic until everyone’s plates were full. Jude took three pieces of bacon, two crackers, and some cheese.

Gabe swallowed hard and asked a detailed question about an insurance claim Jude had filed the week before.

“Really, Gabe?” Linda rolled her eyes. “What a boring question.”

And that made Josh snicker. Ben almost snorted the milk out of his nose. They chewed and murmured about the food and agreed it was good.

Linda cast her eye over the table. “Hey, Jude, you’re missing salad!” She sounded excited to make this simple discovery, picked up the salad bowl, and held it out. She waited for Jude to take it.

“No, thank you,” Jude said.

“Ah, come on.” Linda pushed it closer, glancing at the boys. “I didn’t roast pine nuts for these guys.”

“Really, thanks,” Jude said. “Noel doesn’t like vegetables.”

Linda’s expression stayed in place. The salad hung in mid-air. The boys stopped chewing. Gabe looked over at his brother. Jude didn’t understand why they had all stopped eating when they had seemed so hungry a moment before. Then he realized what he had just said and why the salad still hovered.

“Sorry,” he said. “I meant . . . the vegetables, he didn’t . . . like them.”

“You okay?” Gabe asked, his voice gentle.

“No,” Jude whispered.

When he was young, Jude thought he would stop having nightmares. He imagined growing up was supposed to be about leaving all of his childhood fears behind. Now that he was older, he knew life didn’t work that way. He was still scared, but the things that terrified him had changed. His greatest fears no longer came when his eyes were closed. They appeared when he was awake. He had to stand and watch.

The day after the diagnosis, Noel asked, “What will happen to me?” Jude didn’t know what to say. All he could do was pull Noel close and hold the boy until he tried to wiggle free.

Noel started treatment. He sat attached to a tube, a needle in his arm, the drugs loaded into a clear bag. Jude stayed beside his boy, shifting in a plastic chair, pressing feet flat on linoleum tiles, fighting the urge to rip the syringe out, pick up his boy, and run away.

It was nearly impossible to watch the poison solution drip. Instead of running, Jude grasped for things that were still the same. He bought apple juice from a vending machine, retied the boy’s left shoelace, thanked the two nurses twice each; he smiled, he tried, and failed, to find words that might make Noel feel better.

Noel was a perceptive only child, who thought of his mother’s face as a smudge. He was a creature carefully attuned to his means of survival. With a sniff, he sensed Jude’s inner struggle, pulled over the small table, and suggested they draw to pass the time. Noel got to work with crayons, spreading wax on paper to make a large green alien.

“Dad?”

“Yeah?”

“I don’t want to worry you,” Noel said, peeling back the paper on a crayon to expose the green nub. “But I’ll be leaving soon.”

“Is that right.” Jude forced his voice flat. “Where are you going?”

“Aliens dropped me off when I was born. When I turn eight, they are coming to get me.”

“Where will they take you?”

“Back to our planet. We’ll travel to galaxies to help other aliens when they need it.”

“Sounds like important work.”

“It is.”

“I’ll miss you,” said Jude.

“I know.”

That summer, even as the cancer chewed through Noel’s cells, his body grew in defiance. His face lengthened. Jude watched the chub of childhood cheeks melt just enough for him to catch a glimpse of the future. Noel’s limbs extended around him, but his muscles couldn’t keep up. Soon his knees looked like a man’s fist interrupting the line of a boy’s leg. He lay in bed, sweating. Jude pulled back the sheet and fanned him with a magazine.

Noel looked down at his knees. “I don’t like how they stick out.”

“They are the best knees I’ve ever seen.”

The boy sounded shy and lowered his voice. “I wish they were smaller.” Jude assured Noel that his leg muscles would grow around his knees, but that turned out not to be true. From that day on, Noel’s strength started wasting away.

The passing year turned into months. Jude hoped Noel could live to see Christmas, the same day as his eighth birthday.

Noel didn’t start school in September. Instead, they did things like drive to Gabe’s house for a visit. Noel was too weak to play ball hockey with Josh and Ben, but they found old Lego sets to build with Noel.

It became hard for Noel to keep up with friends. Between appointments, the boy and his dad started spending their time quietly at home together. They ate waffles for dinner, extra syrup, no peas, and no one mentioned broccoli; life was too short and precious. Before bed, they climbed onto the large trampoline that took up most of the space in their small backyard. Noel couldn’t jump, so they lay on their backs and looked up. Noel said he could feel how the earth tilted on its axis. They downloaded an app that showed the constellations. They learned the names of a few favourites, Ursa Major and Ursa Minor. Noel turned a skeptical eye to the sky. “Is there really a bear up there?”

“No,” Jude said, understanding that this question came from a maturing mind. Soon, Noel’s childhood beliefs would start falling out like baby teeth. “I guess we all pretend to see a bear.”

“But there’s no pretend,” Noel countered. “I see stars right in front of my eyes and there are spaceships and aliens and stuff all over. I just don’t see a bear.”

Jude nodded and tried another angle. He explained to Noel how early explorers set sail for lands they didn’t know. There were no maps. They used the stars to navigate and find their way home. Noel considered this far-off reality, then shrugged, unimpressed. “Maybe they should’ve got GPS.”

By early December, the months became weeks. Noel could no longer leave the hospital, but he found joy in the remote control for his hospital bed. He used his thumb to manoeuvre until the tilt was just right for a pilot. “Hang on, Dad,” said Noel. “I’m sending us into hyperdrive.”

Jude grabbed the arms of his chair to brace. “The speed of light?”

“No, faster,” Noel said, explaining for the millionth time. “We jump into hyperspace to travel across the universe through another dimension. It’s like time folds in, like two halves of a piece of paper. We zoom through the middle.”

Maybe Jude didn’t understand the idea of time folding because time had lost all meaning. A year, a month, a day—he started measuring moments instead. They bought a string of holiday lights. The only ones left in the store by then came with separate bulbs, but Noel enjoyed twisting in each light. Once hung, they helped him sleep. He was scared of the dark.

And each good moment became a reason to add more. Jude and Noel would look forward to doing something fun—anything other than needles and tests and blood work. When it was done, they would twist the next bulb into the strand to make it shine. Every moment together added up to something brighter. Soon the lights defined the edges of Noel’s small room. “We live in this galaxy now,” he said.

They talked about what Noel wanted from Santa. He asked for the same thing that he had wished for two years in a row, the Death Star Lego set. “But I know it’s too much,” he quickly added, watching Jude’s face. “It won’t fit in the sleigh, for starters. And 4,000 plastic pieces is too many for one kid. Isn’t that right, Dad?”

Jude nodded as if playing poker. He didn’t tell Noel he had bought the Death Star set the day before. It was almost $600, yes, but Jude felt steadied when he slapped his credit card down on the counter, a kind of insurance.

Jude wrapped the box and wrote a card. “With love from Santa,” it said. He brought the Death Star to the hospital the next day, thinking they could celebrate early. When Jude parked, he saw the number of Noel’s doctor flash on the face of his phone. A tumour had responded to a drug they hadn’t tried before. Jude didn’t allow for hope, but he didn’t want Santa to appear suspiciously early either. He left the Death Star in the trunk.

What Noel talked about the most, the one thing besides Lego and Santa, was the new Star Wars movie. By then, Jude knew Noel would never go to high school, on a date, or even play shortstop that coming spring, but he could look forward to a more complete understanding of the Skywalker family tree.

“Dad?”

“Yeah?”

“Why can’t Jedis get married?”

“You mean in Star Wars?”

“I mean in real life. There is a rule. They can’t get married.”

“I don’t know.”

“I’m going to be a Jedi.”

“Does that mean you want to get married?” Jude asked.

The question ended the conversation. Noel clamped his lips into a tight line and gave his dad a stern look. “That’s gross, Dad,” he said. From then on, Jude didn’t talk about the future. They would stay in a timeline together.

They spent hours speculating about who might be a Skywalker brother or sister or mother or father in the Star Wars movie. Noel confessed—“I’m scared only because maybe I won’t get to see it ever.” He did get to watch it. A nurse downloaded a copy of the movie within a few days of its release. Noel worried they were stealing from George Lucas. Jude promised it was all right and gave Noel a wink. “Don’t worry; George owes me a favour or two.”

“Really, Dad?”

“No.”

Noel lowered his voice. “No jokes like that, please.”

And though the movie didn’t provide all the definitive answers that Noel had hoped for, he loved it. Jude would never forget the look of rapture on the boy’s face as he watched, thin bones bathed in the warm light of the computer screen. While the credits rolled, they lit up a whole new string of lights.

Josh and Ben came to visit the next day. They were impressed that Noel had seen the movie before them and asked all about it. Noel took their willingness to listen and tolerate plot spoilers as a sign of the deepest respect. “They can barely believe I’m their cousin,” he said after the boys left.

Noel wanted to visit the stars again. The Death Star was so big that they might be able to see it at night. When Jude asked the head nurse for permission, she put a finger to her lips. “Ssssh,” she said. “I never heard a thing.”

They climbed up to the hospital roof early to watch the day fade. Jude had the boy wrapped in his jacket to keep warm and carried this cocoon up the metal stairs. His shoes landed on each step with a hollow clang.

“Your feet sound like they belong to stormtroopers,” Noel whispered.

“I am like that,” Jude whispered back. “Part dad. Part machine.”

Jude shouldered out the heavy fire door, and they stood out on the rooftop. The buildings spread out forever. The sky was clear and strong, and they craned their necks to look up. Jude pointed out their house in the distance. They took a selfie with the tall buildings standing like guards behind them. The sun bled away from the edges of the sky and soon the light flattened. The dark moved around them.

They used Jude’s phone to find the constellations. Noel noticed how the sky had shifted since they lay on their backs on the trampoline. He found a new shape in the stars, a large wrestler, which he tried to show Jude by outlining it with his finger.

“See? That’s his knee, and his nose is above that. He is wearing a tight bathing suit.”

“Wait—point to his head?”

“Can’t you see it, Dad?”

“I think I can?”

“He calls himself Charles,” Noel said, knowing his dad was lying.

Jude laughed, and they agreed Charles was a great name for a wrestler; a name like that would command huge respect inside the ring. When they returned to the hospital room, Noel twisted a new bulb on the strand of holiday lights. One light stood for all the stars. And Charles.

Noel had trouble sleeping that night. Jude twisted, restless and uncomfortable, in the hospital chair. Sometime deep in the night came a whisper.

“Are you gone yet?” asked Noel.

“I’m right here,” Jude said, leaning over to switch on the strings of lights for comfort.

Noel was within days of turning eight when the years seemed to shift into reverse. Jude stayed at the hospital every night. He could hold his boy in his lap again. He spooned food into Noel’s mouth, changed his pyjamas, and bathed him in warm water with a sponge. Noel lost the strength to resist being small. Jude let his lips brush the top of the fuzzy remains of Noel’s hair.

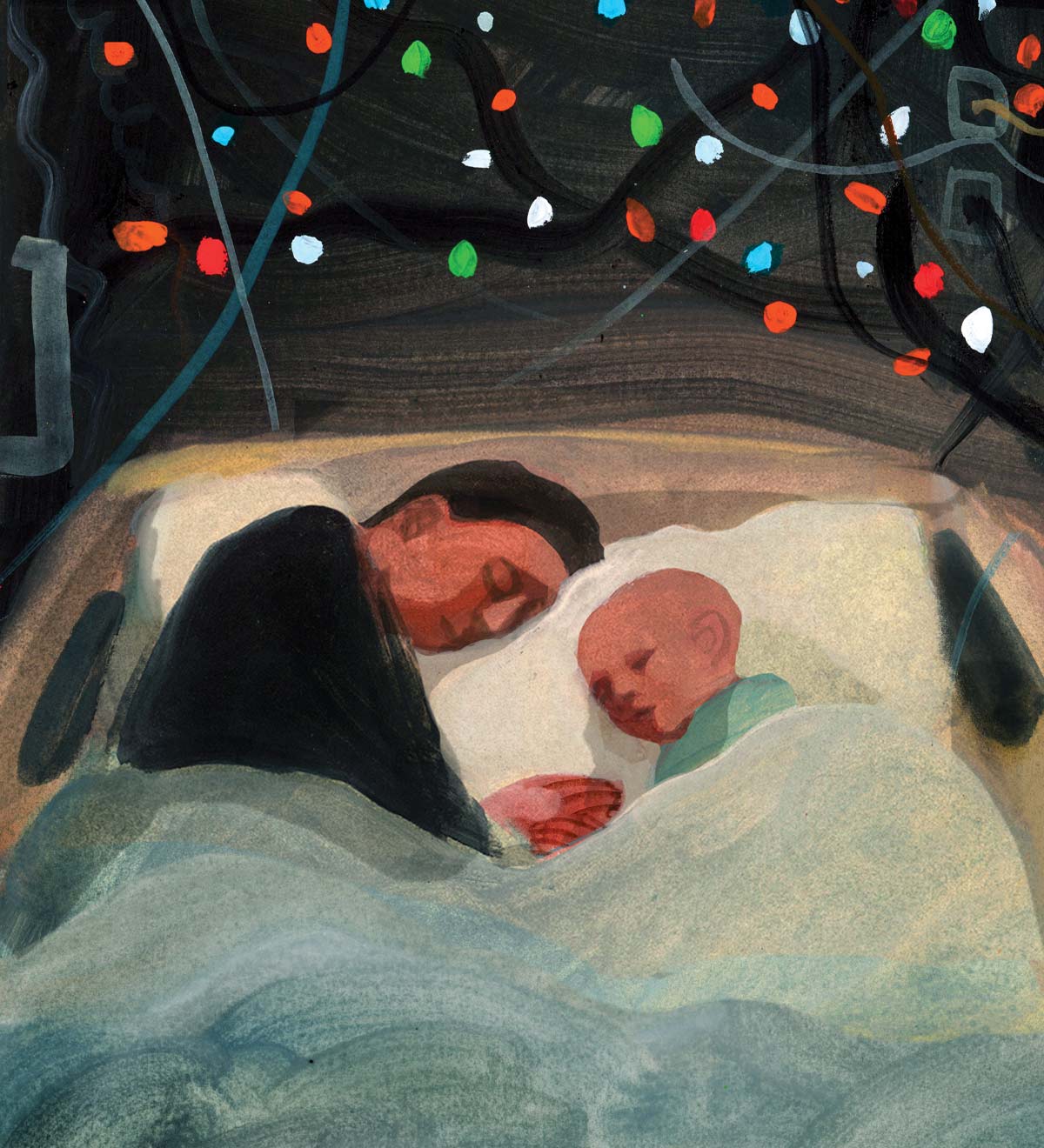

Jude climbed into the bed to hold the boy when he shivered. They tried to pretend there wasn’t a web of tubes around them. Noel nuzzled into his dad’s shoulder, quietly sedated. His bones were slight and the fat was gone, but there was so much more to him than his physical shape. His eyes still burned with life. When the sun caught his skin through the window, it almost shone. When a needle pricked his skin, the blood was a radiant red. The heat from his body felt vibrant enough to glow.

Jude rested a hand on Noel’s belly and felt it rise with each breath. When it was quiet, he could hear the beat of the boy’s heart. His pulse was steady and strong. Jude didn’t believe in God, but he did believe in physics. Energy doesn’t disappear; it is stored or it changes form. It can’t just go.

Noel’s mom, Zoe, left her new baby in Vermont to drive up to see Noel. Jude watched them lying together on the bed. He wanted to place their boy back inside her for protection. Once, she had supplied Noel with everything he needed: blood, warmth, and nourishment. Now all she could do was kiss his soft head.

Outside the room, Zoe gave Jude a long hug. “You are more to him than we could ever be.” But once she left, Jude doubted what she had said. His useful functions were gone. The only thing he could do was squeeze a pain pump. It wasn’t enough.

The nurse talked Jude through the process of dying. She said some people experience a surge of brain activity at the end, a leap of the imagination that feels like reality. For Noel, time might stretch out. He could perceive his life as long and full. She was trying to offer assurance that this death might not feel tragic. To Jude, it was only an end.

That night, a nurse had to pry the pump from Jude’s fingers. “It’s time to let him go.”

Noel died three days before Christmas. The sun was thin and pale and had just crept into the sky. They had left the strings of holiday lights on that night. The bulbs became fainter as the sun took over. Jude was too terrified to sleep for more than twenty minutes or so by then. Noel lifted his eyelids slowly.

And as if some kind of current connected them, Jude immediately woke up from a fitful doze. He knew the pain was bright, and when he fingered the pump, Noel blinked once: “no.” He opted for a lucid look out the window at a city street leading to a big wide world that stretched out for miles and miles beyond his horizon.

“Dad?”

“Hey, Noel.”

“I’m becoming something else.”

“Okay.” Jude crawled gently into bed beside him. “It’s okay.”

“It’s almost Christmas.”

“We’ll get a tree.”

“Can you write Santa a note? I need you to tell him where I’ll be.”

“Yes, of course,” Jude whispered.

He lay with Noel as the boy’s chest levelled out. His heart stopped beating. The room went still. His eyes never opened again, but Jude could still hear him breathing.

Ayear and two days later, Jude woke up in a silent house. It was Christmas Eve. He went downstairs to start the coffee. The gurgle of the percolator, the tick of the clock—he closed his eyes and heard the sounds of their life. For over seven years, he had followed the rhythm of Noel’s play. It started with the sighs of sleep through the monitor, a wake-up cry, and the soft grunts of effort when Noel tried to escape from his crib. With time the sounds grew louder and fuller, and guessing became harder. A soft thump and then the padding of feet: Noel had hopped out of bed and gone on the run. Was the gate across the top of the stairs? These sounds had sent Jude running too.

As Noel grew, the sounds had changed, and still, it had been Jude’s job to hear everything. His eardrums tightened; the sensitive membrane became finely tuned. He could distinguish the clicking of Lego blocks from the pieces of a puzzle; the thumping of drumsticks was different from the whack of a wood sword. The clash of lightsabers came with an entirely different tone, the buzz and hum as they idled. Noel battled a friend, fought against his stuffed bear, or talked to Yoda. All those sounds, the ones that filled the house, were no longer made out loud, but Jude could still hear them.

The phone rang and startled Jude. It was Gabe double-checking that dinner was still on, as Jude had a recent habit of cancelling. When he hung up, Jude looked at the back door and saw Noel’s skates hanging on a hook. The running shoes were on the mat; no one had used or moved them. A Blue Jays backpack sat on the floor where it was thrown after the last day of school. Jude knew what Noel would say as he slung it over his shoulder again. “Well, I’m all ready to go.”

On the kitchen counter sat a stack of mail. Jude took a sip of coffee and opened a card. Inside was a photo of Noel’s camp in Vermont. There was a note from the director. “Noel, we missed you so much last year. Did you go somewhere fun?”

Five casseroles were stacked in the freezer, each with the name of a person who loved Jude written on masking tape and stuck to the bottom. The funeral had been just after the holidays last year. Many friends and family had come to Jude’s house with their arms full of baking and food and flowers, but he had found it difficult to talk. Gabe had worked the door. Linda had stacked food in the freezer, and it sat. They might be full of the spicy stuff Jude had once preferred—Tabasco, paprika, and hot peppers—but he hadn’t touched them.

Instead, Jude boiled a hot dog, cut it into one-inch tubes, and ate it slowly with a fork. No ketchup. He spooned the last of the chocolate syrup into a glass of milk and stirred. Often, for dinner, he ate plain noodles slathered only in butter. Memory became a thing he could chew.

The milk in their fridge had chunks. The curds plopped like wet cheese in the sink. “Dad, that’s gross,” came the voice. Jude agreed and pulled his coat from the hook and walked to the corner store.

The houses in their neighbourhood in Toronto were built close. When Noel was little, Jude would walk with Noel in the stroller to the daycare or the library or to catch the streetcar. When Noel became a toddler, he wanted to walk by himself. It used to take them hours to waddle down the block. Mr. Silva, their neighbour, lived five doors down. He always came out to say hello with a stash of treats to give to the kids who passed by, but he kept special candy just for Noel. Mr. Silva would call out from the porch, “Son, you are Christmas every day!” Noel’s eyes would light up as a small candy cane appeared in his hand.

The lace curtains twitched. Jude kept walking, hoping to slide by in silence, but the door latch clicked and Mr. Silva appeared. His cheeks were wet and shining, and he took forever to shuffle to the end of his shovelled path. Standing close, he dipped his head in a small bow. “I went to church this morning,” he said to Jude. “I said a prayer for my Christmas friend there.” He held a hook of red and white candy.

Mr. Silva waited for a child’s hand to stretch out and take the candy cane. Jude looked down to see it hovering in the air. And then a jolt, stars blurred by, and Jude lifted his eyes to look at the man, but now it was a salad bowl hovering in front of him. He saw a hand with a wedding ring holding onto it and an arm, thin, covered in velvet, stretched over a tablecloth. He followed the arm to find Linda holding onto the bowl. She waited for Jude to take it.

At the other side of the table, Josh and Ben sat frozen, a fork halfway to a mouth, an unwiped moustache after chugging milk. They had stopped talking. They were staring at Jude. A series of silent questions slid across their faces, and he knew they were wondering if they had said something wrong. Was Noel hiding? Maybe the last year had been some kind of sick joke.

The next moment, a pain flashed across Ben’s face. “Noel is dead,” he said.

Linda said no, but yes, and then no again. Gabe stood up quickly. A pain pierced Jude’s chest; he clutched it. He didn’t want to be there, he needed to leave, it had been a mistake to come, too soon. Not yet. He said nothing as he pushed away from the table, grabbed his coat, and rushed out. The key fob jangled in his pocket. He fumbled. Mistakenly, he popped the trunk.

“Jude?” He heard Gabe calling from the house.

Jude slipped on the icy drive, righted himself, and went around the car to slam the trunk so that he could make his escape. With one palm on the glass of the window, he caught a glimpse inside. The Death Star, still wrapped, sat in the back. He had driven around with it all year. His fingers trembled against the back windshield.

“Hey Uncle Jude,” Josh called out, his voice cracked. “Come back?”

The family stood at the door. The light outlined their shapes, the warm house behind their bodies; there was too much distance between them.

“Please,” said Gabe. “Jude.”

“I didn’t mean to say something true,” Ben was sobbing.

It was the sound of Ben’s cry that stopped him, a cousin’s voice like a recording. It broke Jude open. He stood still, trying to breathe, eyes falling on the large box. “I brought you guys something,” Jude lied. “I wanted it to be a surprise.”

He popped the trunk. It took more courage than he could imagine to lift the large box out of the car. With the Death Star in his arms, he almost slipped. Gabe came to help, and they made it back through the front door. Linda took Jude’s coat. He carried the wrapped box into the living room and set it down near the tree. The family gathered around.

“So huge,” said Linda. “What is it?”

The boys already knew. They started shouting and ripping off the paper. Ben confessed he had always wanted this but never asked. “I knew Dad would freak.” Josh appointed himself the director of the building process.

“Best present ever,” said Ben.

Outside the window, the stars lined the sky around the house. Gabe set a fire. He turned on the lights on the tree. Linda made coffee and passed around cookies. The boys started piling clear bags of bricks. Josh gave Jude the job of collecting all the instruction booklets. Stacked together, they were as thick as a Bible.

A log on the fire crackled. Small plastic bricks started to click.

Jude went to the window and craned his neck to look out. Maybe the blur of tears made them multiply, but he could see thousands of lights. It was like every bulb in the galaxy had been twisted. Five points of light clearly defined the tight bathing suit, the boots, the broad shoulders, the tough-guy expression. Stark and bright, standing in the middle of the night, stood a wrestler named Charles.

Noel must be close.