Detective Joe Ricci and his partner, Alex Sinclair, were out on a routine bust in Vancouver’s Chinatown. It was 1916, and Ricci and Sinclair were front-line officers in the war on opium. The drug had been criminalized in Canada eight years earlier through the introduction of the Western world’s earliest drug prohibition law, and the Vancouver police department had been chasing down traffickers ever since. Ricci was a familiar sight in the neighbourhood. He had made such a big arrest in 1913 that for days after, the Vancouver Daily World reported, “not a light [was] to be seen and the ringing noise of the chuck-a-luck dice [had] stopped.” But the gamblers and the opium smokers were soon back, and Ricci was out patrolling the streets again.

This time, something went wrong. As Ricci and Sinclair moved in to make the arrest, one of the smokers threw an opium lamp at them—the den erupted into flames, trapping them. Sinclair grabbed an axe and hacked his way through the wall as smoke filled the room. The two cops narrowly escaped.

By 1920, with the enactment of a new, tougher law, news stories of police pursuing Chinese opium users and pushers had become commonplace. “Chinks Pay Heavily for ‘Hitting Pipe,’” read a headline in the Prince George Citizen that December. The local chief of police, they wrote, “has been busy of late in the prosecution of the heathen Chinee for dallying with the forbidden opium. Under the new Opium Act it is perilous for an Oriental to be found in possession of this drug either for purposes of smoking, chewing or snuffing up the Chinese nose.” But no one was more influential in drawing a causal nexus between race, crime, and drugs and then embedding that connection in the public imagination than “Janey Canuck,” who shocked Canada with a series of articles published in Maclean’s that same year.

Janey Canuck was the pen name sometimes used by Emily Murphy, an Edmonton-based writer and temperance advocate who was also a pioneering feminist and the first female magistrate in the British Empire. Murphy was the lead instigator of “The Famous Five,” a group of five women, who, in 1927, launched the petition that began the celebrated Persons Case, which argued that women were indeed “persons” under the British North America Act and therefore eligible to serve in the Canadian Senate. Although her advocacy on behalf of women’s rights is the most celebrated part of her legacy, her role in the criminalization of drugs, including marijuana, has been no less important. Her anti-drug crusade is a classic illustration of moral entrepreneurism. Drugs were bad, but more evil still in her calculus were people of colour, who used them to subjugate white Canadians. Murphy lent her authority to and popularized a racialized theory of drug use that was used to justify the expansion of draconian legislation in the early 1920s. She was not the first public figure to exploit nativist prejudice to advance an anti-narcotics agenda, but she, along with her predecessor Mackenzie King, was among the most significant in the moral transmutation of drugs from benign private indulgence to public evil.

The Opium and Narcotic Drug Act of 1929, which was largely a realization of Murphy’s legislative ambitions, remains to this day the framework for Canadian drug laws. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has promised that the latest iteration, the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, will soon be significantly amended. As we wait for the passage of these belated reforms, it is worth examining why it has taken so long for reason to replace prejudice when it comes to drug policy. Our misguided approach began with the story of Emily Murphy, and the story that she told Canada—a toxic tale of racism and moral panic. The resulting criminalization has long been subject to moral reconsideration. Only now does it seem ripe for legal reform.

There were two populations of North American opiate users in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The larger, by far, was composed of many hundreds of thousands of middle-aged, middle-class white Americans and Canadians dependent on an unregulated market in opium-fortified remedies and cure-alls such as laudanum. Those addicted to these patent medicines were chiefly women. They were regarded as suffering from a medical misfortune or personal vice—these addictive elixirs were not regarded as a menace to society, unlike alcohol, which was increasingly viewed with suspicion.

Those members of Chinese immigrant society who smoked opium made up the second and much smaller using group in Canada. Initially welcomed as a cheap source of labour, the Chinese in British Columbia became objects of hostility as they found themselves competing with an influx of white workers for a dwindling number of jobs. Canadians increasingly demanded that Chinese immigration be restricted or curtailed, and beginning in 1885, a “head tax” (graduated from $50 to a prohibitive $500 by 1904) was imposed on every new migrant from China.

Continuing job insecurity and local newspaper provocations led to anti-Asian demonstrations in downtown Vancouver in September 1907. Full-scale riots ensued. Mackenzie King, then deputy minister of labour, was dispatched to Vancouver to conduct a one-man inquiry and provide reparation to those Asians, both Chinese and Japanese, who had suffered property and business losses during the rioting. King was affronted when he received claims from several provincially licensed Chinese opium merchants. Moving well beyond his mandate, and guided by local anti-opium advocates, King undertook an unofficial investigation into the opium trade in BC. He was quickly satisfied that opium smoking “was making headway, not only among white men and boys, but also among women and girls.” In King’s view, set out in his report to Ottawa, remaining indifferent to the scope and gravity of “such an evil” in the country would “be inconsistent with the principles of morality which ought to govern the conduct of a Christian nation.” He pressed for criminal prohibition of the importation, manufacture, and sale of opium. Only that destined for “medicinal purposes”—that is, to satisfy the cravings of white consumers—was to be exempted.

Two and a half weeks after King submitted his report, Canada’s first criminal narcotics legislation—which reflected all of his proposals—was drafted. It then passed without debate in the House of Commons and was soon given royal assent. Anti-Asian sentiment, particularly that emanating from Vancouver, undoubtedly helps explain the absence of any opposition. No other Western nation had criminally prohibited the non-medical distribution of narcotics; similar American federal legislation, the Harrison Narcotic Act, was not passed until 1914. The penalties set out in the 1908 “Act to prohibit the importation, manufacture, and sale of Opium for other than medicinal purposes” included very stiff fines and imprisonment for up to three years. (In contrast, the Proprietary or Patent Medicine Act, tabled the same year to regulate the contents and labelling of narcotic medications, carried a maximum penalty of a $100 fine or twelve months in prison—despite the fact that such medications carried a greater risk of drug addiction.)

King’s fingerprints are all over the next several generations of drug legislation. The Opium and Drug Act of 1911 added cocaine and morphine to the schedule of illicit substances. Mere possession of a prohibited substance was made a criminal offence, extending the reach of the law beyond traffickers to addicts and casual opium smokers. The amended Opium and Narcotic Drug Act of 1920 further amplified both the scope and the harshness of the criminal law. The RCMP was formed the same year and became both the policing arm of the federal Health Department and Canada’s first centralized drug enforcement agency. Further amendments in 1921 and 1922 increased maximum penalties to seven years and granted the police extraordinary powers of search and seizure.

Those who did express occasional disquiet about the proposed erosion of civil liberties were mollified by assurances that the rigid sanctions would not be visited on “ordinary citizens”—that is, non-Chinese Canadians. The Senate agreed that “dwelling houses” should be exempt from warrantless searches. Police enforcement efforts, the Senate reasoned, would not be compromised by the amendment: Chinese users and dealers, the true focus of these efforts, tended to live—unlike law-abiding Canadians—in their stores or in contiguous shacks. The health minister reported to Parliament that nearly three-quarters of the convictions secured between 1921 and 1922 had involved “Chinamen.” The possibility that such measures might someday target their own grandchildren appears never to have occurred to Canadian legislators.

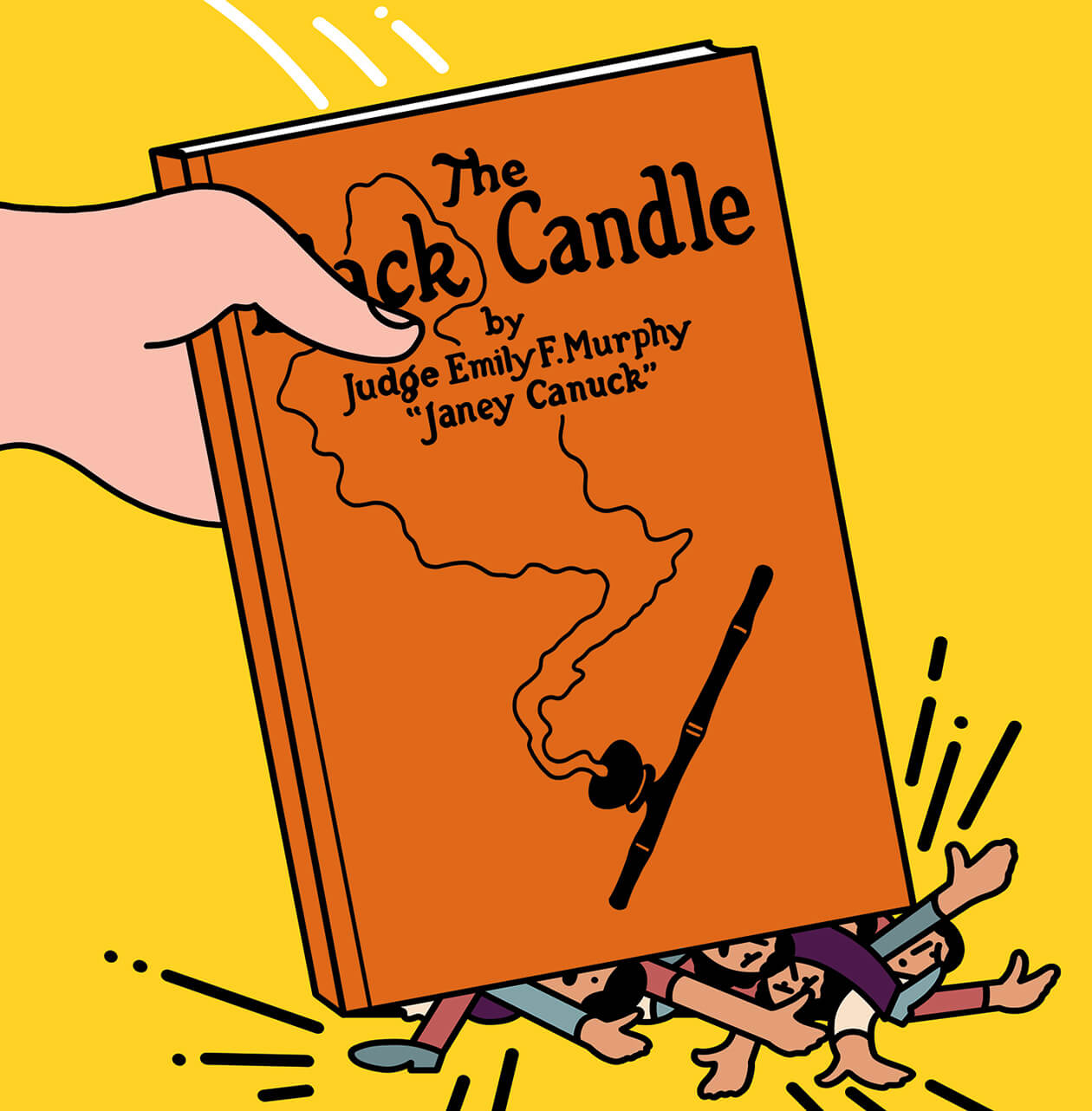

Some civic groups condemned the non-medical use of opiates and cocaine, but these drugs were secondary players: it was alcohol that the vocal and well-organized temperance movement identified as the fountainhead of sin. Although the legislators who made frequent enhancements to the criminal law routinely invoked the horrors of Chinese drug peddlers, the general public outside of Vancouver and Victoria was little concerned with the subject of drugs. That changed in the 1920s, when Maclean’s magazine commissioned a series of sensationalist articles by Emily Murphy. The articles were later expanded and republished as a book, The Black Candle, in 1922. While Murphy’s magnified sense of her own crusading importance has undoubtedly contributed to her notoriety, her influence cannot be denied. Catherine Carstairs, a professor of history at the University of Guelph, has tried to deconstruct Murphy’s inflated stature. “Nonetheless,” she allows, “Murphy’s articles did mark a turning point, and her book, which drew heavily on the Vancouver [anti-drug] campaign . . . brought the Vancouver drug panic to a larger Canadian audience.”

The Black Candle was dedicated to reversing what Murphy portrayed as profound public indifference to the widespread consumption of drugs: “It may be stated without fear of error,” she writes, “that the lack of public sentiment is the chief reason for the halting gait of the law on its way to enforcement.” Governments were equally negligent, she contended, because they “have failed to grasp the seriousness of the situation,” and “the sums allotted to dealing with the drug traffic have been entirely inadequate—indeed pitifully so.” Her articles and book had the desired effect. They attracted widespread media attention, galvanized a previously apathetic citizenry, and enabled a broad expansion of the scope and severity of drug control legislation. Maclean’s was so pleased with the moral panic Murphy’s first article triggered that an editor’s note encouraged newspapers and the public to join the crusade: “It is only through an aroused consciousness of the gravity of the situation . . . that the menace can be successfully grappled with” and “much more stringent prohibitory laws” secured.

A firm subscriber to the contagion theory of social pathology, Murphy urged drastic measures—including mandatory imprisonment, deportation, and whipping—to suppress the “evil” of drugs, as “a single drug user in a community should be considered a menace to the whole of it.” All of Murphy’s legislative proposals were soon reflected in the criminal law. (Murphy also recognized that an effective solution required therapeutic initiatives, but her recommendations in the area of addiction treatment were entirely ignored by both Parliament and the Department of Health.)

Some apologists claim Murphy was simply a product of her times. It is true that she did not invent racism: the indignities visited on Chinese, Japanese, Sikh, and black immigrant populations, among others, were but a natural, if less murderous, extension of the same systemic discrimination experienced by Canada’s Indigenous peoples. Racism is baked into Canada’s DNA, and Murphy both understood and shared the values it promoted. She struck a deeply resonant chord as she exploited racial bigotry to advance her anti-drug campaign. “There is,” she writes, “a well-defined propaganda among the aliens of colour to bring about the degeneration of the white race.” The role of villain in her accounts was uniformly played by “foreign” persons—most frequently Asian (“Chinamen”), sometimes black (“Negroes”—“many [of whom] are obstinately wicked persons”) and, on rarer occasions, “Jews.” Lest her point be lost on slow readers, The Black Candle was illustrated with lurid photographs of white women reclining in opium dens with black men.

But when it comes to drug policy, Murphy was the author of her times, not its historical artifact. Murphy did not just sign on to social-justice issues; she publicly championed them, promoting eugenics and, more specifically, the coerced sterilization of “mental defectives.” Murphy’s bigotry toward persons of colour was at least as strong as her commitment to the cause of female equality. Nor were her racist attitudes culturally inevitable. Helen Gregory MacGill, for example, was Canada’s third female jurist and Murphy’s contemporary. Like Murphy, she was a popular national journalist and ardent feminist. Unlike her, MacGill never incited racial prejudice to advance her concerns about the exploitation of women.

To dismiss Murphy’s fulminations as little more than colourful background to the intensification of Canada’s drug laws would be to do a disservice to both the power of her rhetoric and her historical impact. More than any other single source, Murphy’s puritanical, anti-immigrant writings were responsible for promoting the “dope fiend” mythology and fuelling the moral panic that informed drug legislation for decades. Other stakeholders such as the RCMP, the federal Department of Health, and anti-vice agencies played their part in the campaign, but it was Murphy’s celebrity and her inflammatory advocacy that set the table for the punitive excesses that followed. As Brian Anthony and Robert Solomon note in the introduction to the re-publication of her book in 1973, “The Black Candle, which now may be dismissed as grim humour or condemned as outright propaganda, was a landmark both in the life of its prominent crusading author and in the history of Canadian drug legislation.”

Most important for the current debate is the fact that Murphy was the first public figure to draw attention to “Marahuana—The New Menace,” as one of her chapter titles put it. That the recreational use of marijuana was virtually unknown in Canada did not concern Murphy, who pressed her case by favourably quoting Charles A. Jones, a Los Angeles police chief:

Persons using this narcotic, smoke the dried leaves of the plant, which has the effect of driving them completely insane. The addict loses all sense of moral responsibility. Addicts to this drug, while under its influence, are immune to pain . . . While in this condition they become raving maniacs and are liable to kill or indulge in any form of violence to other persons, using the most savage methods of cruelty.

Murphy failed to note that Jones’s tenure as the chief of the LAPD lasted less than six months, and she selectively cited the supportive claims and opinions of like-minded advocates in Britain, the US, and Europe. Murphy, however, made no mention of the preeminent study of the time, the report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission—although she would almost certainly have been aware of it. A model of early public inquiries, the British-Indian commission was created in response to a question raised in the British Parliament about the deleterious effects said to be associated with “hemp drugs” (marijuana and hashish) in imperial India. The commission released its 3,281-page report in 1894. The null hypothesis—that cannabis consumption led to insanity—was readily debunked. Indeed, the commission concluded that moderate cannabis use “is practically attended by no evil [physical] results at all,” “produces no injurious effects on the mind,” and “produces no moral injury whatever.” They also concluded that, “for all practical purposes it may be laid down that there is little or no connection between the use of hemp drugs and crime.” Murphy, though, was not going to let evidence get in the way of her crusade.

Absent scientific research, public dialogue, or any challenge from a cowed medical community, it is perhaps not surprising that in 1923, only a year after The Black Candle was published and fifteen years before US federal legislation followed suit, cannabis joined opium, morphine, and cocaine on the schedule of prohibited drugs. Tens of thousands of Canadians have been jailed and hundreds of thousands more burdened with criminal records as a result. Yet not a word of Parliamentary debate accompanied this amendment.

Murphy was far from unaware of her importance, and she was not shy when it came to self-promotion. In 1923, she nominated herself for a Nobel Prize for her anti-drug efforts. As for the pending scourge of marijuana about which she warned a blissfully naive nation—the first reported police seizure did not occur until 1937.

Canadian drug legislation was consolidated and then renamed the Narcotic Control Act in 1961. The penalties for drug-related offences were by then much more severe than those that had been in force in the wake of The Black Candle. Cannabis remained scheduled with cocaine and pharmacologically true narcotics such as morphine and heroin. This persistent misclassification has had significant consequences. From 1961 to 1977, the share of convictions involving opiate narcotics declined from 98.3 percent to 1.3 percent, while convictions relating to cannabis increased dramatically. A penal regime intended to deter the distribution and use of arguably pernicious substances was overwhelmingly visited on consumers of marijuana, which, even by the late 1960s, was generally recognized as relatively benign.

At the same time, drugs historically confined to criminal and ghettoized communities spread to college-age populations—as did arrests, convictions, and imprisonment. Mounting public and media pressure prompted the federal government to strike a public inquiry in 1969. The Commission of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs, popularly known as the Le Dain Commission, was charged with investigating this phenomenon and making recommendations. Drawing on empirical evidence and applying rational measures of harm, the commission concluded in its final report that the criminalization paradigm was unjust, unfair, and ultimately unsound. A severely penal approach to drug use was, it reasoned, a failed social policy that ruined far more lives than it salvaged, while enabling the very criminality it was intended to repress. Members of the commission also recommended that simple marijuana possession be decriminalized and that the penalties for production and distribution be dramatically reduced.

The work of the Le Dain Commission attracted an unusual degree of attention from the media and the public, and there was a palpable sense that legislative reform would follow the release of the commission’s final recommendations. They have had, however, little effect on the statutory landscape over the intervening forty-plus years. A similar Senate inquiry begun in 2000, the Senate Special Committee on Illegal Drugs (or Nolin Committee), fared no better. Its bipartisan recommendations—including that cannabis be licensed for distribution to persons over sixteen and that all those ever convicted of possession of the drug should receive amnesty—were greeted with equally profound official silence.

Simple possession of cannabis remains a criminal offence, and one that is widely enforced. Nearly 50,000 cases of cannabis possession were recorded in 2015—more than half of all criminal drug incidents. And despite popular sentiment and the direction of scientific research, penal sanctions have only intensified over the past decade. Merely passing a joint between marijuana users remains a criminal offence subject to a term of imprisonment.

Still, a number of recent developments signal that reason will ultimately triumph over morality. Cannabis is now recognized as medically beneficial for some conditions. A growing number of authority figures in the fields of science, medicine, law, and law enforcement have publicly sided with reform positions. And, of course, there is the shared experiential reality of Canadian consumers. Public-opinion polls mirror these developments: support for the decriminalization of personal possession of cannabis rose from 55 percent in 2003 to 71 percent in 2014. Set against this background, the Liberal Party’s 2015 campaign promise to legalize cannabis once elected was neither radical nor politically risky.

The racist origins of Canadian drug legislation should not be forgotten. As the Le Dain Commission noted in its 1970 Interim Report: “There can be no doubt that Canada’s drug laws were for a long time primarily associated in the minds of its legislators and the public with general attitudes and policy towards persons of Asiatic origin.” But what the Le Dain Commission neglected to consider is that racial inequities continue to flow from our reliance on a prohibitionist model of drug control.

Street-level narcotics users and their hand-to-hand suppliers are those most exposed to law enforcement. Their repeated arrests, and the longer sentences that accompany each conviction, funnel them into a revolving door of drug-fuelled criminality. Inevitably, this population is disproportionately poor, marginalized, recently immigrated, or relocated—in short, it is made up largely of people of colour, including Indigenous persons, who make easy pickings for the police. The vulnerability of racialized Canadians to harsh sanctions is largely a product of institutionalized poverty and despair: structural discrimination with intergenerational consequences.

Race maintains its power to kindle a connection between drugs and crime in the public imagination. The explicit imagery that ushered in the criminalization of drugs a century ago is now filtered through the barely coded language of class, neighbourhood, and country of origin. “Carding,” an offensive police procedure founded on racial profiling, would never be tolerated if it targeted white communities. The role of race in the crafting of drug policy is a not an historical aberration. Drug laws continue to give cover to systemic racism, and the racially uneven effects of their application must be addressed in any future legislation.

While the Liberals may be tempted to take the middle ground, the architects of any new drug-control model need to understand that an assessment of harm must include not only the effects of drugs on their users, but also the broad compass of social harms associated with alternative drug-control regimes. These range from sustaining a criminal industry and financing its expansion to undermining confidence in the law and other democratic institutions. Meanwhile, the artificially inflated cost of prohibited drugs drives addicts to commit collateral crimes such as burglaries, muggings, petty thefts, and prostitution. Overdoses and the transmission of disease through shared needles are additional, and sometimes fatal, downsides of continued prohibition. Concerns about stigmatization and police intervention impede access to even voluntary treatment and counselling.

The war against drugs has really been a war against people, many of them barely past childhood. The Le Dain Commission, like the Nolin Committee a generation later, understood this. Political will has almost caught up with their forceful pleas for the application of reason, and their sound judgment will be vindicated by the pending legalization of recreational cannabis. The recognition that the problems associated with dependence on “hard” drugs are better approached as matters of health than criminal policy will perhaps eventually also find purchase. These days, drug dependence is increasingly seen as a matter of personal or circumstantial misfortune rather than a moral fault. The current opioid epidemic and the gentrification of addiction have contributed to this redefinition. The closer the user demographic is to the levers of privilege and power, the more likely the problem is to be framed as one that requires doctors rather than police.

While drug use is inevitable, a dysfunctional approach to its management is not. We need to recognize both our regulatory mistakes and their consequences. We need to craft laws that are grounded in medical and social science, that favour education over punishment, that urge inveterate users to adopt safer drugs and methods of consumption, that sustain personal and public health, and that criminally target only those traffickers who exploit the young and vulnerable. The minister of health, Jane Philpott, said nearly as much when she told the United Nations last April that Canada intended to “introduce legislation . . . that ensures we keep marijuana out of the hands of children and profits out of the hands of criminals.” Logic, science, and good sense all tell us that this noble commitment should inform any discussion about the regulation of recreational drugs. Abstinence is a delusional and unenforceable policy goal; on the other hand, the minimization of harm is a socially worthy and achievable objective.

Progressive policy initiatives require courage, collective intelligence, and meaningful consultation with both user and therapeutic communities. The vested interests of law enforcement must cede to those of public-health professionals. Dogma, from whatever side, needs be replaced with empiricism, the experience of reformist nations such as Portugal and Uruguay, and sensitivity to the historical implications of the task. George Bernard Shaw, another contemporary of Emily Murphy, expressed the nature of the challenge thus: “It is much easier,” he said, “to write a good play than to make a good law. And there are not a hundred men in the world who can write a play good enough to stand daily wear and tear as long as a law must.”

We are on the cusp of a defining moment in our nation’s social contract—one that favours science over ideology and public health over a reflexive resort to the criminal law. So long as the mantra of harm reduction remains central, we may, at least in this one small domain, achieve a measure of personal and social justice.

This appeared in the January/February 2017 issue.