The Happily Ever Esther Farm Sanctuary, about sixty-five kilometres southwest of Toronto, is home to around sixty-five rescued farm animals, including pigs named Hercules, April, and Len, a goat known as Diablo, and a cow whose moniker, Pouty Face, perfectly matches her cuddly demeanour. These animals have come from a variety of places: some are from petting zoos, some have literally fallen off of trucks, and one was abandoned at the sanctuary’s front gate, presumably because its owners could no longer care for it. Other animals hadn’t been cared for at all—two of the sanctuary’s eight sheep were found, still squirming, on a farm’s so-called dead pile, where cast-off cadavers are heaped. Many of the animals at the sanctuary are factory-farm refugees, raised expressly to be consumed. At Happily Ever Esther, they will instead live out their natural lives in comfort and safety.

The animals, or “residents,” as the owners of the sanctuary prefer to call them, inhabit the twenty-hectare farm: the pigs stay in the main barn plus one fenced-in hectare of roamable forest and one of pasture; the chickens overnight in a sun-dappled enclosure also inhabited by two Muscovy ducks and a couple of garrulous peacocks; a few cows, a horse, and a donkey occupy a four-hectare paddock; and a colony of rabbits lives in a condo-like complex known as Bunny Town. But Happily Ever Esther’s eponymous resident lives in neither barn nor paddock. Rather, Esther, a 650-pound, six-year-old pig, shares a farmhouse with the sanctuary’s proprietors, Steve Jenkins and Derek Walter. She has her own bedroom, just off the entrance to the house, though the room has become a bit dingy—the broadloom is stained, the cupcake-patterned wallpaper peeling—as a renovation, which will open her room to the backyard, is imminent. But Esther usually prefers the sunroom, where she can snooze on a tattered, queen-size mattress. The first floor of the house could, in fact, be called Esther Town—paintings and photographs of the pig cover every wall, and porcine sculptures and other tchotchkes occupy most corners. On a shelf above Esther’s mattress are copies of the books that Jenkins and Walter have written about her, as well as a throw pillow emblazoned with “CHANGE the WORLD.”

In many ways, Esther exists far beyond her faded room or even the sanctuary itself. Online, she is known as Esther the Wonder Pig. Close to a million and a half people follow her on Facebook, about half a million on Instagram, and 50,000 on Twitter. On social media, Esther’s life is documented in detail, even if her life pretty much consists of sleeping, sleeping, palling around with a turkey named Cornelius, wearing silly wigs and outfits, sleeping, snuggling her dads, and sleeping. Her YouTube channel, on which Walter and Jenkins also host an occasional low-tech cooking show, whipping up “Esther-approved” vegan dishes, has more than 22,000 subscribers. She is the Kim Kardashian West of the hog world, making appearances on, among other shows, ABC’s Nightline and the CBC’s The Nature of Things. In early March, Walter and Jenkins released their first children’s book, The True Adventures of Esther the Wonder Pig. In July, they published Happily Ever Esther: Two Men, a Wonder Pig, and Their Life-Changing Mission to Give Animals a Home, with a foreword by actor Alan Cumming, a sequel to their 2016 New York Times bestseller, Esther the Wonder Pig. An Esther store, housed in a grey-and-pink trailer on the sanctuary grounds, sells Esther-themed jewellery, T-shirts, onesies, calendars, and toques. An autographed photo of Esther—signed with a rubber stamp of her hoofprint—goes for $20. In 2016, Walter and Jenkins began an annual Esther Cruise, a week-long Caribbean cruise during which the couple regales passengers with multimedia presentations about the sanctuary. (As people-friendly and housebroken as she may be, Esther does not go on the ship.)

For several years, animal shelters and rescue centres have used social media to find homes for pets, and most farm sanctuaries now have at least a rudimentary online presence. Happily Ever Esther, however, was created in reverse: Esther was a social-media phenomenon long before she inspired Walter and Jenkins to open the sanctuary. “Social media allowed us to introduce an animal like Esther to people in a way that was previously impossible,” Jenkins says. “We’re just two people that started in a house in Georgetown that are now able to reach between 4 and 7 million people every week on Facebook. And we didn’t spend a dime to do it. Fifteen years ago, none of this would have happened. We would still have Esther, but nobody would have known about her.” And with that unprecedented awareness came an unexpected responsibility—if people cared this much about one funny pig, couldn’t they, shouldn’t they, care about the welfare of all pigs? And, by extension, all animals?

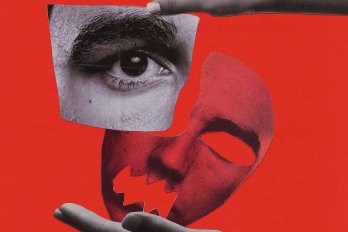

Esther’s hardly the only animal celebrity on the internet. You might have heard of, or just as likely thrilled to, the trials and tribulations of Doug the Pug, Grumpy Cat, Cecil the lion (RIP), or the adorable animals that endlessly populate the popular Instagram account @chillwildlife. Social media highlights our confused, curious relationship to animals—both object of worship and object of scorn, just like us and absolutely foreign to us, disappearing and always present—but it also fulfills the fundamental human desire to somehow collapse the wall between their world and ours. Virtual experiences of the natural world allow us, in an unexpected way, to forge relationships with animals that zoos and circuses and safaris can’t allow: intimate, fantastic, and shamelessly anthropomorphic. Esther’s social media knocks down that wall almost entirely—with her bizarre, pampered, highly visible life, she is reshaping how hundreds of thousands of people, if not more, see an entire species. The paradox is that the more Esther lives like a human, with all the contradictions that entails, the more she reminds humans that animals are deserving of lives as rich and full as our own.

Steve Jenkins narrates Esther the Wonder Pig and, in the book, comes off as self-deprecating, sentimental, and unabashedly corny. In person, however, both he and Walter are thoughtful and clearly devoted to their work. The two met in 2001 at a restaurant in Mississauga, Ontario, where Jenkins worked as a bartender and Walter a tableside magician. Jenkins was not quite out then, but they started dating and have been together ever since. Jenkins, thirty-six, is lean and dark haired, with the perma-grin of a porpoise; Walter, a year older, has reddish-brown hair and a fondness for jaunty neck scarves. In the few times we met over the course of a month, they were usually dressed in Esther-branded merchandise, like T-shirts that read, “Peace. Love. Esther.” or freebies from the likes of Amy’s Kitchen, a vegetarian food company.

Three years after they met, the two moved to Georgetown, a small community about an hour’s drive from Toronto, where Jenkins became a real estate agent. They were typical animal lovers, with a handful of dogs and cats, until 2012, when Jenkins received a random Facebook message from a friend trying to off-load a twenty-centimetre, six-month-old mini pig she said she’d bought off Kijiji that wasn’t getting along with her dogs. Jenkins jumped at the opportunity. “A mini pig?” he thought. “That sounds adorable. Who wouldn’t want a mini pig?” But Esther, as it turned out, was not a mini pig. There’s no such thing as a mini pig breed, even though breeders use the terms mini pig or micro pig or teacup pig to pass off young and underfed pot-bellied pigs as a smaller, cuter pet. And after Jenkins had persuaded Walter to keep her, after they had house-trained her, sort of, after they had convinced their respective families that they weren’t insane, sort of, only then did they realize that their new pet was, in fact, a commercial pig that could easily reach 700 pounds. But they didn’t want to give her up. Esther was playful, cuddly, and as affectionate and smart as their dogs (she could open any locked cupboard, for one thing, and, when being housebroken, quickly learned to pretend to pee in order to get a treat). They fell in love with her, and after just a few weeks, she had taken over their lives. They stopped eating pork and, a few months and a couple of documentaries later, gave up eating meat entirely. They also, as recounted in exhaustive, comic detail in Esther the Wonder Pig, pig-proofed their house. It basically meant reordering their lives around Esther—rarely leaving her alone, removing any and all food from the kitchen (if she didn’t eat it, she’d happily redistribute it, be it basmati rice or canola oil, all over the house), and cleaning up, in Jenkins’s words, “prodigious amounts of piggy pee and poop.”

They also started posting pictures of Esther on Facebook. Cute, sweet, funny pictures. Esther curled up with the dogs! Esther scarfing down cupcakes! Esther in a dress in a kiddie pool! Like any proud parents, Jenkins and Walter wanted to share with far-flung relatives images of their newest family member. But, instantly, the pig’s page started attracting followers they didn’t know. The page was shared by Toronto Pig Save, an animal-rights organization that holds vigils for pigs on their way to slaughter. Other animal-rights and vegan groups likewise shared it. The general public got wind of it, and as noted in Esther the Wonder Pig, ten days after Jenkins posted his first picture, Esther’s Facebook page had more than 6,000 followers. A month later, it had 30,000. “It was just happy messaging,” Jenkins says of the reaction. “Everybody’s used to seeing, in the vegan world, when you’re trying to advocate for pigs, pigs upside down without any heads, stuff like that. And here was a full-sized pig in the house, sleeping on the couch.”

Walter and Jenkins encouraged plant-based eating and animal advocacy on the page but eschewed hard-nosed activism or any whiff of confrontation or extremism (assiduously avoiding the word vegan, for one thing). Their message was two pronged: it promoted animal rights, and coming from a gay couple, it also celebrated tolerance in general. Jenkins quotes the humanitarian Paul Farmer in the epilogue of Esther the Wonder Pig: “The idea that some lives matter less is the root of all that is wrong with the world.” This kinder, softer approach seemed to work: Jenkins and Walter were overwhelmed by people who told them how just seeing Esther, a happy pig hanging out with happy humans, had led them to stop eating meat, or opened their eyes to how intelligent pigs really were, or even, in the case of one septuagenarian in Montreal,helped them learn English. Less than three months after the couple had launched Esther’s Facebook page, she had over 100,000 followers. Animal activism has always had a marketing problem, but Esther is, undeniably, a solid brand.

The attention was dizzying. But it also posed a threat. Jenkins and Walter suspected that they couldn’t legally keep a commercial pig in their 1,000-square-foot home in suburban Georgetown. (They were right—it is, in fact, illegal to keep “swine” on non-agricultural-zoned land in the area.) But, now fully vegan and far more aware of animal-welfare issues than they were pre-Esther, Jenkins and Walter had an idea. They knew from Facebook that there were hundreds of thousands of people, and probably many more, who supported them, their pig, and the ideals they espoused. The “Esther Effect,” as Jenkins had termed her life-changing impact, could be even bigger. What if they left Georgetown, bought a farm, and opened a sanctuary for other rescued farm animals?

It had been done before and with great success. In 1986, in Wilmington, Delaware, the young animal-rights activists Gene Baur and Lorri Houston rescued a sheep from a stockyard’s dead pile in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and began Farm Sanctuary, an organization dedicated to educating the public about factory farming. It later grew into a home for rescued farm animals, including “downers,” those that can’t stand on their own and are often put down. In its early days, Farm Sanctuary bankrolled its operations by selling veggie hot dogs at Grateful Dead concerts. By 1990, with more diverse fundraising efforts, Baur and Houston moved to a rundown, seventy-one-hectare farm in upstate New York, where an ambitious cadre of volunteers took care of around 150 rescued animals. Farm Sanctuary now runs three sanctuaries (the two others are in California) that are home to about 1,000 animals in total, with the organization’s expansion paralleling the rise in public awareness of animal welfare and plant-based diets. In 1999, outside of Stratford, Ontario, Siobhan and Peter Poole opened Cedar Row Farm Sanctuary, Canada’s first farm sanctuary, rescuing hundreds of neglected, abused, and unwanted animals. (They currently take care of eighty.)

An accurate, up-to-date count of sanctuaries in North America is hard to come by, but the Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries currently lists 145 that provide homes for farm animals and also chimpanzees, elephants, and tigers that have had previous lives in labs, entertainment, or the exotic-pet trade. Sanctuaries are meant to be homes for animals rather than places for humans to come and gawk. While traditional zoos and aquariums still like to think of themselves as agents of conservation and education, creating otherwise impossible connections between human and creature, sanctuaries suggest a different lesson: animals should be preserved for their own sake, not ours.

Neither Jenkins nor Walter had ever worked on a farm before or even knew how a sanctuary might work. But they had never owned a pig before either. And, with Esther, they never had to consider selling veggie dogs: four months after the Facebook page began, and two years after they’d adopted Esther, they launched a crowdfunding campaign that raised almost half a million dollars in two months. In 2015, they purchased twenty hectares of fields, forest, and farm buildings called Cedar Brook Farm and renamed it Happily Ever Esther Farm Sanctuary.

Around one in the afternoon on a cold day in early March, Walter welcomes me into the farmhouse and leads me through a dark foyer furnished with carpet mats, a wood-burning stove, and various articles of foul-weather gear, which are scattered about. We walk through the small kitchen, where a half-eaten pizza rests on a cutting board. Nearby is a small table and desktop computer, from which Jenkins runs Esther’s various social-media accounts. And then, there, right next to Jenkins’s makeshift office, is Esther herself, sprawled on her side on her sunroom mattress. A red rubber dog toy and larger plush doughnut lie beside her.

Even though I’ve read all of Esther’s books and seen countless photos and videos, I’m still not quite prepared for meeting her in the flesh. I might well have walked in on Cleopatra reclining on a divan or stumbled across an alien life form accidentally left behind by her spacecraft. She really is enormous, as big as a couch. Paler than expected, too, less pink than white, an effect of the light-coloured bristles that cover her entire body. I’m less surprised to see that she seems to be asleep. I instinctively bend down to hold my hand to her nose, figuring that, like a dog, she’d want a sniff. “No, I wouldn’t do that,” Walter says. “Let her come to you.” Esther doesn’t move. I pull my hand back.

While her size is startling, even more so is seeing such an animal lounging around the house like a sitcom teenager. But the real weirdness comes less from anything animalistic and more from the fact that she is a celebrity. I feel that same stupid shiver of recognition and mild awe that sometimes accompanies the public sighting of a famous movie star or musician or athlete. Later, I sit next to her, somewhat warily, as Walter takes my picture. I want to touch her, and he tells me where to put my hand, about midway up her side. I place it there gingerly, as if about to get a manicure. It’s like resting my hand on the side of a 650-pound hot-water bottle, if that hot-water bottle were wrapped in a wire-brush welcome mat. Esther smells faintly, mysteriously, of maple syrup—something I later learn is a common odour of some pigs.

Even when I sit in the living room to talk with Walter, I keep glancing at Esther across the room like I’ve spotted Angelina Jolie at lunch in Manhattan. She still doesn’t move. But now, I think, it isn’t because she’s a pig who needs to sleep all day; rather, it’s because she’s a diva who can sleep all day. When Jenkins and Walter first moved to the farm, they gave Esther the choice of where to sleep, thinking that, with all this new space, she might choose the barn. But, aside from the brief moment on the factory farm where she was apparently born, Esther has never lived among pigs and has had no desire to live among pigs; aside from Cornelius the turkey, she barely consorts with the other residents. Jenkins and Walter, along with the cats and dogs she grew up with, were her herd. She chose the house.

Staring at Esther and talking about the strange twists her life has taken, I find it impossible not to think about my own somewhat eccentric, arguably sentimental, relationship to animals. I’ve never hunted, never farmed, haven’t been fishing in decades. But I’ve lived my life among animals, many of them pets, many others random creatures who took up residence in my brain and never left. I was named, the story goes, for my father’s friend’s pet parakeet. When I was in my early twenties, living near San Francisco with my parents, we had a chick named Henry that grew into a hen, and a delightful one at that. She perched on the kitchen counter while we made dinner. You could stroke her beak, right between her eyes, and she would topple over to sleep in your lap. Then there’s our runty, neurotic, ten-year-old tabby, Beans, whose skin condition once left her nude as a newt; my cousin’s pit bulls, Gaia and Nova, so abused by their former owners that they’d tremble if unfamiliar people so much as stood next to them; the sad-eyed orangutan who posed with my seven-year-old self in a Singapore zoo, his arm draped heavily around me; the day-old kitten I rescued from a dumpster but which was accidentally smothered when the tiny thing crawled into bed; cows I’ve milked and lambs who’ve suckled my fingers; and the dogs I’ve had to give up, the cats I had to put down, the fish I just didn’t “get.”

Outside of country fairs, I never came very close to any pigs. I’ve read lots about them, though, and know that they’ve always received a bad rap. “The 10,000-year history of the domestic pig is a tale of both love and loathing,” writes Mark Essig in Lesser Beasts, his cultural history of the animal. People still think pigs are lazy, dirty, and gluttonous. And so many of us really, really, really love bacon. I haven’t eaten meat in about twenty-five years, and I have been more or less vegan for the last eight. I’m not opposed to killing animals for food per se, but I hate the horrific and unnecessarily cruel way most livestock are raised, confined, and slaughtered. For all the bougie zeal for family-run farmers’ markets and farm-to-table restaurants, we still routinely consume products from industrial-scale factory farms, or, as they’re called by the US Department of Agriculture, “concentrated animal feeding operations.” I’m lucky. I live in a progressive, cosmopolitan, affluent country with a historically unprecedented amount of choice in what I eat. And, for me, those options don’t have to include animals like the pig peacefully snoozing in the next room. This is certainly the most tangible part of the Esther Effect—she’s made a lot of people feel the same way.

Peter Wohlleben asks in his book The Inner Life of Animals, “Why isn’t the image of the smart pig publicized more? I suspect it has to do with eating pork. If people knew what kind of an animal they had on their plate, many would completely lose their appetite.” But pigs, as I’m learning at Happily Ever Esther, are actually extremely clean, loyal, social, and occasionally ornery—and they firmly believe in hierarchies. They share a number of cognitive capacities with chimps, elephants, and dolphins—including understanding simple symbolic language, playing video games, having excellent long-term memories, and possibly exhibiting empathy. Pig lovers are fond of saying that pigs are as smart as three-year-old children. And, when you meet a pig, especially one like Esther, when you actually spend some time watching a pig, feeding a pig, and playing with a pig, their intelligence and ability to connect doesn’t seem far fetched at all. We sometimes replace valves in human hearts with those from porcine hearts. Supposedly, human flesh tastes an awful lot like pork. Like celebrities, pigs are just like us. Celebrity pigs maybe even more so.

Taking care of a 1-percenter pig is demanding enough. Running a farm full of now privileged animals, all with their particular needs and personalities, is something like hosting a perpetual telethon at a petting zoo. It’s a unique job that is equal parts animal psychologist, tour operator, and carnival barker.

The same day I meet Esther, Walter gives me a crash course in farm-sanctuary management. He and Jenkins basically run two businesses: Walter is an employee of Happily Ever Esther Farm Sanctuary while Jenkins is a social-media manager and content creator employed by Esther the Wonder Pig. The Esther merch helps pay the expenses of the farm. Walter and Jenkins have divvied up the labour accordingly. Walter, who took the four-day course at the Farm Animal Care Conference at Gene Baur’s Farm Sanctuary and has learned much about farm life through trial and error, manages the animal-care team. But he also takes care of Happily Ever Esther and Esther administration, overseeing staff (nearly a dozen full- and part-time employees) and volunteer teams, monitoring ten different email accounts, coordinating fundraising campaigns, and managing charitable donations. (Happily Ever Esther is a registered charity, though Esther the Wonder Pig is not.) Jenkins sits on the board of the sanctuary and spends his days writing the books, taking the pictures and videos, and running the social media. Walter estimates it costs about $1,000 a day to run the sanctuary, an amount which covers, among other things, feed, medications, vet bills, and staff salaries.

Given that many of the residents’ lives pre–Happily Ever Esther were anything but happy, the animal-care staff spends a lot of time on the residents’ mental health. Each animal, when it arrives, is given what Walter calls a “freedom name,” and when Walter takes me to meet the various residents, he bellows these names with great enthusiasm and pleasure. The animals respond, prancing or meandering toward us, eager for an ear scratch or belly rub. I’ve never seen farm animals so delighted by human company. I spend at least ten minutes rubbing the soft, dehorned head of a goat named Catherine, as if I were on ecstasy.

I return to the farm the following morning for a workday. It’s unseasonably chilly, but nonetheless, about twenty-five volunteers show up. Everyone gathers around a firepit in the middle of the sanctuary, gripping cups of coffee and tea, and Walter, wearing a fluorescent-yellow toque, stands up to greet them. “Welcome to the happiest place in the world,” he says. After a brief orientation, the volunteers fan out across the property to spend the next four hours removing old, semifrozen straw from paddocks, raking dried manure, and chopping down a few diseased trees. When they pass by the farmhouse, I notice many of them craning their necks to catch a glimpse of Esther inside, some holding up their phones to get a picture. While most of the volunteers are there because they are animal lovers, their day actually includes very little contact with the residents. In fact, Walter says, they shouldn’t even make eye contact with one of the sows. “April’s in heat,” he says. “And it’s a rager.” Not that April would attack any of the volunteers, but an unfamiliar human could overexcite her and cause her to accidentally trample or butt one of the younger pigs that swarm around her.

Even in this hog heaven, pigs will be pigs, and older and bigger pigs eat first. There are rivalries and occasional disputes. One of those disputes, between two male pigs, Captain Dan and Len, both of whom came from a failed sanctuary in Quebec, left Len unable to walk—his back leg was torn open by one of Captain Dan’s tusks. When we visit Len in the barn, I notice a flat-screen TV suspended above him. This, it turns out, is part of Len’s enrichment program. Temporarily unable to leave the barn—a new door is being constructed to allow that—staff are trying to keep him as stimulated as possible. That stimulation includes scheduled movie time, storytime (a box of children’s books is nearby), massages, coconut-oil brushing, toy time, forage bucket time, song time, and snuggle time. Since Len can only really scoot around on his rear, he is also wearing diapers, slipped over his rear legs, to prevent chafing and sores.

Last year, Esther herself fell ill. Out of nowhere, she started to have breathing problems. Her nose turned blue, her rear end purple. Jenkins and Walter thought she might be having a heart attack, and once they stabilized her, they loaded her into a trailer and hightailed it to the animal hospital at the University of Guelph’s Ontario Veterinary College, the foremost veterinary school in the country. As soon as she got off the trailer, Esther had another episode. And then another. The vets could only hypothesize about her illness without being able to diagnose her with a CT scan. And they didn’t have a CT scanner that was big enough. Walter and Jenkins were incredulous. If the OVC didn’t have a scanner large enough for a big animal, like a cow or a horse, what happened to them? Some of them, it turns out, go to Cornell University, in New York, which does have a sufficient scanner. Most of them are treated with the best care the OVC can provide, but if that treatment doesn’t result in a better quality of life, the animals are typically euthanized. Outside of sanctuaries, pigs rarely get to be as old as Esther is, and the ailments that might afflict her are partially the result of her age.

Jenkins and Walter kept Esther at the OVC, where she had blood work and urinalysis done regularly, until she could be returned home to the farm. The couple began using its network of supporters to raise money for a big enough scanner to donate to the OVC, with the proviso that any animal sanctuaries would be able to use the machine at discounted rates. Less than a year later, the fundraiser surpassed its goal of raising $651,000.

This apparent generosity aside, not everyone loves Happily Ever Esther or its proprietors. Walter and Jenkins have been accused of exploiting Esther, criticized for dressing her up in demeaning costumes. They’ve been called glory hounds, just in it for the fame and money. Some think the couple’s high-profile, media-friendly success means other sanctuaries are being deprived of desperately needed donations in the frenzy of following a celebrity. I was surprised by this, assuming that the sanctuary movement, given that it’s filled with presumably altruistic people all devoted to a similar cause, was happy and cohesive. When I mention this impression to Walter and Jenkins, they laugh, then shake their heads. “We came into this differently than other people,” Jenkins says. “We did not set out to be vegan activists. We called ourselves ‘accidental activists’ very early on. We set out to show people how amazing pigs are and what life with pigs was like and to help people relate to them on a different level that would impact them in the same way she impacted our lives.”

One of the big reasons they ended up starting a sanctuary in the first place was because they learned how much trouble some existing ones were in. Not enough money. Unable to keep the animals they supposedly rescued. No succession plans. “We didn’t want to be one of those sanctuaries,” Jenkins says. “Which is, again, why we do things a little bit differently.” Rather than those struggling sanctuaries acknowledging Happily Ever Esther’s success, Jenkins argues, “they get pissed off that their system is still broken.”

“They’re all doing good,” Walter says. “Anybody that helps animals, in my eyes, is doing it out of love. But love doesn’t pay the bills.”

Happily Ever Esther isn’t quite at capacity. The sanctuary has enough physical space and staff to take on more small animals. And Jenkins and Walter get calls and emails every day. But Walter is deliberate about the process. Saying no to any animal in need is heartbreaking, but he has to ensure that taking on another resident won’t upset the ecosystem he and Jenkins have built. (There’s a cute young pig named Tammy B., for example, that has lived with the sheep because the other pigs wouldn’t accept her.) But equally as important is ensuring that the current residents continue to receive a consistent level of care and that the infrastructure at the sanctuary remains intact and effective. If all goes according to their plan, Walter and Jenkins say, in a couple of years, the organization will be sustainable and successful enough that they can step away from the daily grind of the farm. They may still run Esther’s social-media accounts and administration, but they won’t have to muck out the barn.

But how do you really measure success in this world? By the number of animals rescued, the number of donors or volunteers, the number of Facebook followers who bail on bacon? No metric is really adequate. Like climate-change activism and environmental conservation, it’s heroic work that’s also inescapably Sisyphean. I loved being at the sanctuary and even absently fantasized about opening my own. But it also made me feel something I could only describe as a hopeful sadness. In his 1977 essay “Why Look at Animals?” John Berger writes that animals in the first stages of the Industrial Revolution were used as machines. Later, in post-industrial societies, they were treated as raw material, with animals required for food, in Berger’s words, “processed like manufactured commodities.” If factory farming is capitalism in its purest form, the farm sanctuary is arguably one of the purest forms of resistance to capitalism. It restores to these manufactured commodities their full, individual lives. It challenges the natural order of the world. It’s a way to think against blithe brutality, unfettered consumption, conformity, inequality.

On my last visit, I sit with Jenkins and Walter in their living room. Jenkins serves tea and cookies, resting a tray on the red tickle trunk that contains Esther’s costumes. I drink my tea out of a large ceramic mug shaped like a pig wearing overalls. Esther is sleeping in her room, but a mutt named Alice, recently saved from a Korean meat farm, keeps her eye on me from the couch. A question still nags at me, and I pose it to the couple: “You have about fifty-eight residents now, but there are billions of animals that you can never save. Does this ever discourage you? Does it ever feel futile?”

Jenkins looks instantly pained. His eyes well up. “Yeah, it’s tough,” he says. “That’s the hardest part. I try not to go there, because it’s overwhelming.”

Walter agrees. “We do feel helpless, if you step outside this bubble. As soon as you get on the highway, and the trucks are whizzing by, full of chickens and cows and pigs. Before, I used to get super upset and not even look. I’d just cover my eyes, pull the visor down, and get around those trucks.” He pauses. “Now I look right in them and see what’s going on.”