Iwas on my way to the city of Kobanî, in northern Syria, this past spring when I stopped at one of several roadside coffee stands for a break. To my surprise and delight, this particular kiosk had an espresso machine—a luxury, considering most of its competitors served instant coffee.

Amgihan, a twenty-six-year-old Kurdish woman who asked that I use only her first name, told me she has helped manage the stand for the past ten years, eight of which have been during the ongoing civil war in Syria. She has had dreams of adding a small seating area to expand her business, but for years, her world wasn’t stable enough for even so much as a plastic table and some chairs.

Her home was damaged during the incursion of Islamic State militants, a group most locals refer to as Daesh, and she and her husband and children moved in with her father-in-law. Now, with Daesh mostly out of the picture, she planned to return to the expansion project she had long dreamt about.

Amgihan’s ambition is a reflection of the hopes that animated Rojava, a Kurdish-led, semiautonomous territory in northern Syria, when I visited this past spring. (Though many still call the territory Rojava, or “sun sets” in Kurdish, it was officially renamed the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, often shortened to NES, last September.)

Against the backdrop of Syria’s civil war, Rojava seemed to have been emerging as a remarkably progressive democracy that brought together communities of diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds under one secular territory.

I wanted to see for myself how a democracy might fare in this corner of the Middle East—a region largely dominated by authoritarian regimes and torn apart by sectarian conflicts and foreign intervention. In April, I travelled through the territory with Lokman Mirza, a local journalist who had agreed to secure and translate interviews for me. As I listened to the stories of Rojava’s residents, I tried to capture how a seemingly impossible vision was trickling down to their daily lives.

Some told me they referred to the Kurdish-led territory as “the project.” It’s a fitting term for a place that shows promise—although it seems almost too good to survive.

The Kurdish community’s history as a marginalized minority in Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Iran seems to have shaped its vision of Rojava as a tolerant, multiethnic society. In 2014, the territory’s administration installed a new charter that mandates, among other things, equal rights for minorities, gender equality, and environmental protection.

But Rojava’s democracy is under severe threat. The Turkish government, which sees Kurdish resistance as a threat to its power, launched a military incursion on October 9 after Donald Trump greenlit the invasion and the US began withdrawing some of its troops in the region. In the absence of its former US ally, the Kurdish resistance has turned to the Russian-backed Syrian government for help. Some speculate the Syrian regime may use this opportunity to reclaim the region by force; Rojava contains key resources, including oil fields, dams, and agricultural land.

Residents of Rojava also have to contend with the continued trauma of war. The city of Raqqa, to the south of Kobanî, was liberated from Daesh in 2017, but some of the extremist group’s sympathizers remain within the walls of the old part of the city. Suicide bombings, car bombings, and targeted killings devastate Raqqa residents’ daily lives. During my visit to Raqqa, two car bombs exploded, killing nine. With ongoing Turkish airstrikes and ground incursions, some fear Islamic State detainees may escape and remobilize.

Rojava’s most existential weakness, however, may come from within. At least one Kurdish opposition party has accused Rojava’s leading political party of being dictatorial. Human Rights Watch has accused Rojava’s administration and military of human rights abuses and the exploitation of child soldiers; Amnesty International has accused them of committing war crimes. The territory’s governing party is affiliated with the Kurdish Workers Party, or the PKK, which Canada and the United States consider a terrorist organization. Some Arabs describe Rojava’s Kurdish-led administration as a form of occupation.

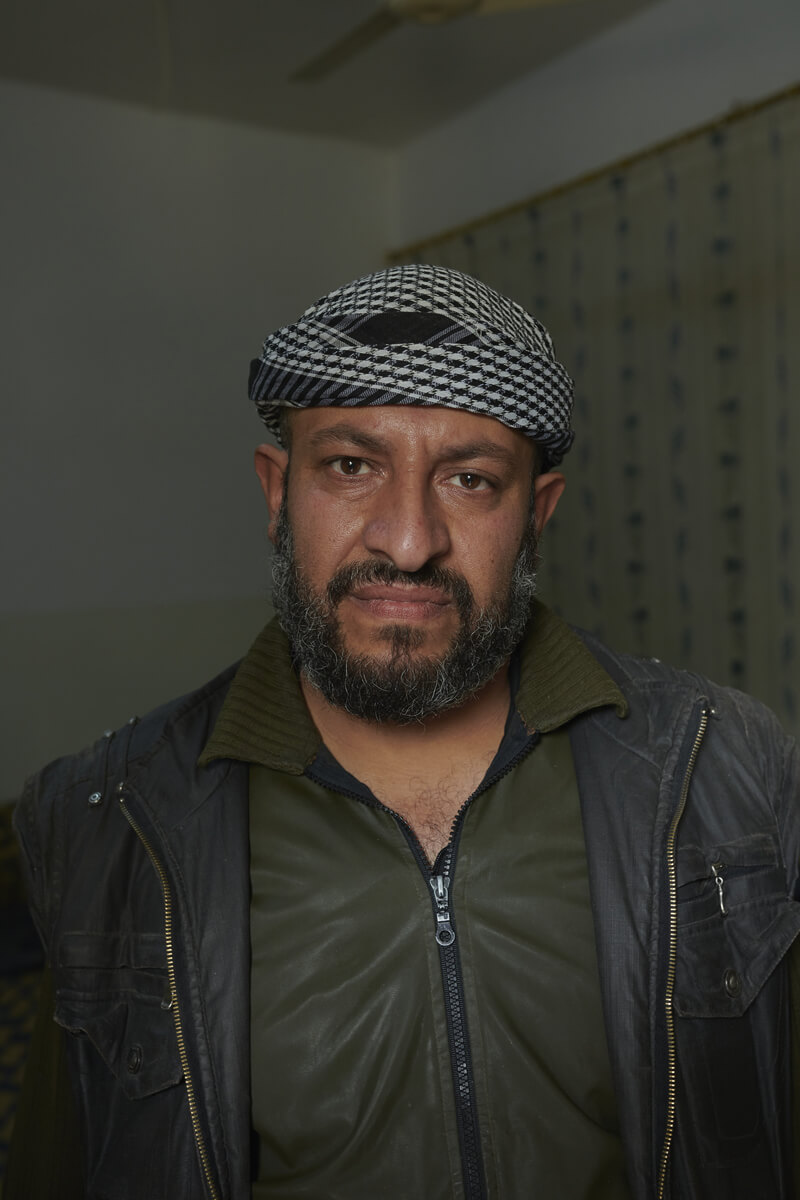

But, to many residents I met, these were minor concerns. “I’ve known the regime of Hafez Al-Assad, of Bashar Al-Assad, of the Free Syrian Army. . . . I don’t want to go back,” Mohammed Khair Al-Shiekh, who is Arab, told me, referring to Syria’s past and current president as well as a militant opposition group. “Today, I’m a democratic Syrian citizen.”

The thirty-nine-year-old former mechanical engineer serves as copresident of the executive council, with a Kurdish colleague, of the city of Manbij and its surroundings. The council oversees public services, such as hospitals, schools, and infrastructure, and as per Rojava’s constitution, all offices are co-led by a man and a woman.

Not all Rojava residents have embraced the project. Some view officials’ attempts to court minorities not as an exercise in inclusion but as a ploy to shore up power against hostile neighbours.

To some Assyrians, for example, the Kurds’ rising dominance has sparked fears of losing their identity. In the Christian village of Tal Jomaa, where many still speak Aramaic, the language likely spoken by Jesus, there are few families remaining out of what was once 450 households. Many of the younger residents have left in recent years, and the town’s seniors see themselves as their community’s guardians.

“It’s been eighty years since we came here from Iraq and built everything. Daesh destroyed everything in one night,” one woman, who spoke fluent French, told me. “The young people will return—they’ve left for Canada, the US, or Europe. It wasn’t their choice to leave their country. They were forced to.”

During our lengthy exchange outside of a café, it became evident that a lifetime of oppressive rule and state surveillance had left their mark. She refused to be named or photographed. “Usually,” she said, “people here don’t talk to outsiders.”