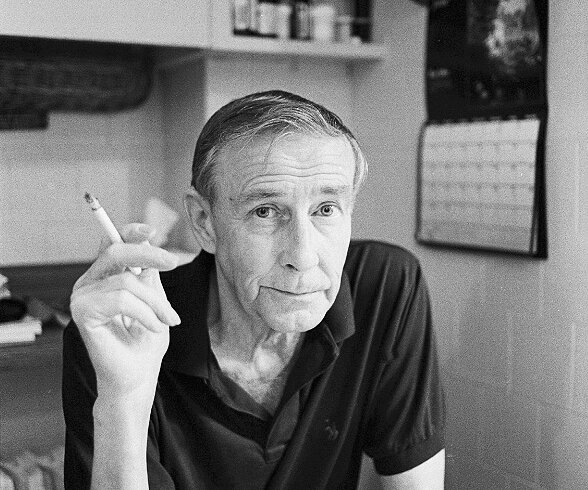

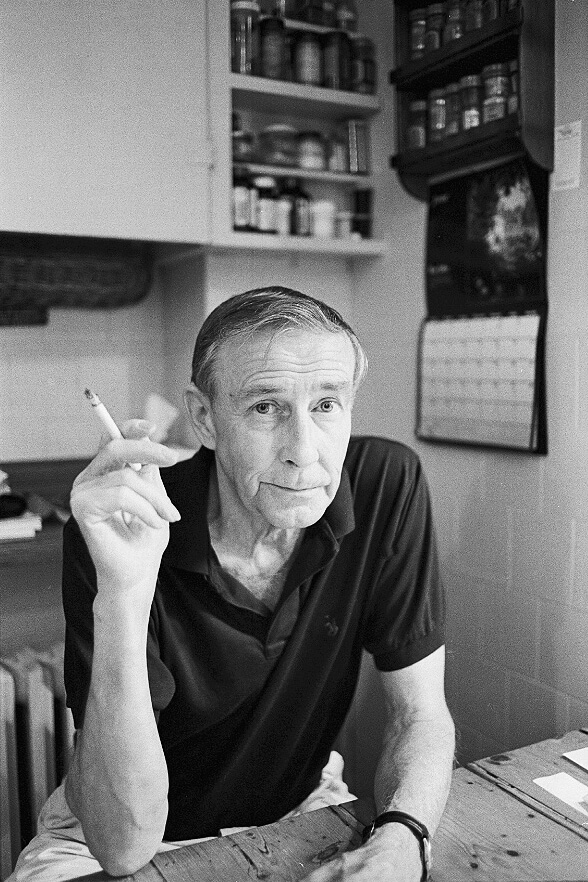

I first interviewed Doug Jones on a snowy day in 1986 at his Houghton Street home in North Hatley, Quebec, in the company of two cats. Our talk was punctuated by his explosive laughter, the occasional thwack of his butane lighter, and one brief cat fight.

He was a fabulous interviewee: charming, forthcoming, and ready to elaborate on any topic I raised. “One of the images I have of a poem and of living,” he said, “is broken-field running. The thing is to keep going and not to fall flat on your face with whatever comes up: bumps, holes, ups and downs, winds, logs.” The range of interests he negotiated was extraordinary. He was into I Ching, particle physics, Japanese painting. In a later interview, it was Taoism, Jacques Derrida, Marshall McLuhan. For over half a century, his mind sped freely over wide expanses of thought—as did his poetry. Poets, Jones claimed, “watch what’s coming up”—they give shape to our vision of ourselves. With his death on March 6, 2016, at the age of eighty-seven, Canada has lost one of its defining voices—a co-creator of the cultural house we all occupy.

Jones was born in Bancroft, Ontario, in 1929, received a bachelor’s degree from McGill and a master’s from Queen’s where he wrote a thesis on the work of Ezra Pound. He taught at the Ontario Agricultural College until he ran into difficulty with a parent who objected to a racy poem by Irving Layton that he was analyzing with his students. After short stints at Royal Military College and Bishop’s University, he settled in at the University of Sherbrooke where he stayed until his retirement.

Jones is today recognized not only as a major poet, but as a translator of the first rank. In 1969, he co-founded, along with Sheila Fischman, the journal Ellipse in which English and French poets were—for the first time—placed side by side in mutual translation. His well-known study of English Canadian poetry, Butterfly on Rock, was published in 1970 and remains an indispensible source for insights into the growth of a distinctive Canadian imagination: “life is now a matter of naming and discovering, “ he wrote, “of finding words for the obscure features of our own identity.” Louis Dudek, Jones’s mentor at McGill, said the study was not literary criticism, but poetry. Jones won the Governor General’s Award for Poetry in 1977 for Under the Thunder the Flowers Light Up the Earth and was made an officer of the Order of Canada in 2007. In all, he published ten volumes of poetry, including a collection, The Stream Exposed with All its Stones, released in 2010.

Poems, wrote Jones, have backbones. They are “stalks of syntax” on which sway flocks of images “which rise and whirl / shifting / like the red-wings in their single cloud then “arrow into statement.” His poems have a wondrous intellectual height: images and perceptions drop, phrase by phrase, down the page in cryptic or ironic notation. From US poets Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams he learned how to construct an image, how to use the white spaces between lines, and how to apply an intense focus on objects as a way of compressing and communicating feeling. For Jones—to use one of his own lines—“Everywhere some small design erupts.” He discovered a kindred soul in Quebec poet Paul-Marie Lapointe, whose poems he translated. When he describes a Lapointe poem as “a series of luminous tracks that betray invisible electrons startled from atomic sleep,” he could be explaining the way his own poetry moves elliptically and unpredictably towards an indeterminate destination.

I Annihilate

I annihilate the purple finch

in the apple treeit is a winter dawn

it is ‘La Guerre’ Henri Rousseau

saw charging through the shattered space

of the Second Empireit is a faint

raspberry

in the silent cosmosc’est une tâche

sur la page blancheun cauchemar en rose

c’est le Québec

librea bird

c’est ça

un oiseau dans un pommierit may fly off

but it won’t go away.I neglected to mention the snow.

By inserting French phrases into his poems, Jones created a neat musical and often ironic counterpoint to the English. Much of his career was spent attempting to close the gap between the two languages. In 1998, he co-edited a fine anthology of Quebec poetry of the late twentieth century, Esprit de Corps. And along with Lapointe, he also translated the poetry of Normand de Bellefeuille, which won him the Governor General’s Award for Translation in 1993 and the poems of Émile Martel’s Pour orchestre et poète seul. He was drawn to Québécois poets who were intellectually and stylistically compact, often hovering on the edge of sense. Jones was instrumental in moving translation away from creative treason, toward a kind of heroic madness which brings special delights. “At least in this country,” he wrote in Ellipse 50, “an argument about poetry or its translation is not likely to produce tombstones.”

As a self-confessed pastoral poet—sometimes his best poems were nothing more than weather reports on rain and snow—Jones sought harmony in his immediate surroundings, which for most of his life meant the village of North Hatley on Lake Massawippi, a twenty-minute drive from Sherbrooke, Quebec. He lived with his wife, Monique Baril-Jones, on the same street as fellow poet Ralph Gustafson and novelist Ron Sutherland. Through much of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, the town—in a tongue-in-cheek coinage by Sutherland—became the Athens of the North, and was site of the annual Seventh Moon poetry readings which brought English and French poets to the same stage in various venues throughout town. North Hatley’s community of writers included mainstays like Rob Allen, Steve Luxton, and Avrum Malus. Three literary periodicals were published during those years. Besides Ellipse, an editorial team at CEGEP Champlain in Lennoxville launched Matrix in 1975 while Allen and others founded The Moosehead Review in 1977 which came out of various cabins in the woods at the southern end of Lake Massawippi. For a while it was indeed as if some sort of regional poetic renaissance was taking place. It didn’t survive the turn of the century; all three literary journals eventually moved out of the region.

I was one of the founding editors of Matrix, and went to Jones seeking guidance before we actually embarked on the mad business of starting a literary magazine. He was both encouraging and candid in his advice during our nearly thirteen years of publication. When I undertook an ambitious article on his poetry and translation, he wrote me a gently qualified compliment, saying I had got it “nearly” right.

Friends and fellow poets mattered. Poetry, for Jones, became a way of staying in touch, keeping people in view, making them part of his human constellation. He dedicated poems to poets Anne Hébert, P. K. Page, Robert Kroetsch, Patrick Lane, Steve McCaffery, Erin Mouré, Al Purdy, and others. There are poems to friends, family members and a very touching elegy to Robert Taylor, his “perfect carpenter,” and who, in the poem, becomes an absence framed by the window Jones is cleaning.

In his later years, he took up computer drawings, composing unique digital sketches full of eye-catching shapes and quick strokes that he would mail out as gifts. I’m not sure when his interest in art started but I remember being part of a life drawing course, in the early ’80s, conducted by Morton Rosengarten in the grungy depths of a yet-to-be-renovated McGreer Hall on Bishop’s University campus. Jones and others were part of the group which produced some rather alarming charcoal renditions of the naked figure. By that point in his career, Jones was already combining an interest in visual art with his practice of poetry. He remarked once how he found confirmation of his poetic technique in a work by Paul Klee that made use of small details, lines, squares, blocks, and stick figures to create serious meaning. Jones’s poetry is a bit like this too; he works on the scale of the phrase, the image, perceptions of detail, asides, thefts, and verbal cartouches, and made them indicators of profound experience. He found a kinship with other Canadian artists, such Alex Colville and especially David Milne. The latter’s light-filled landscapes inspired the poem “A Garland of Milne” which celebrates the artist’s gentle touch in transforming “god-forsaken country” into a garden—“All space came out in flowers / miraculous.”

For Jones, such transformation required openness to the world. “Let the wilderness in,” he wrote in the concluding pages of Butterfly on Rock. His laconic, witty, and verbally ingenious poetry deserves to be read in the light of this injunction. Some of his poems may fall by the wayside because of their topicality (Who will remember Myriam Bédard in the years to come? Or even now?) but the intensity and relevance of his vision, the daring of his broken-field running, will endure.