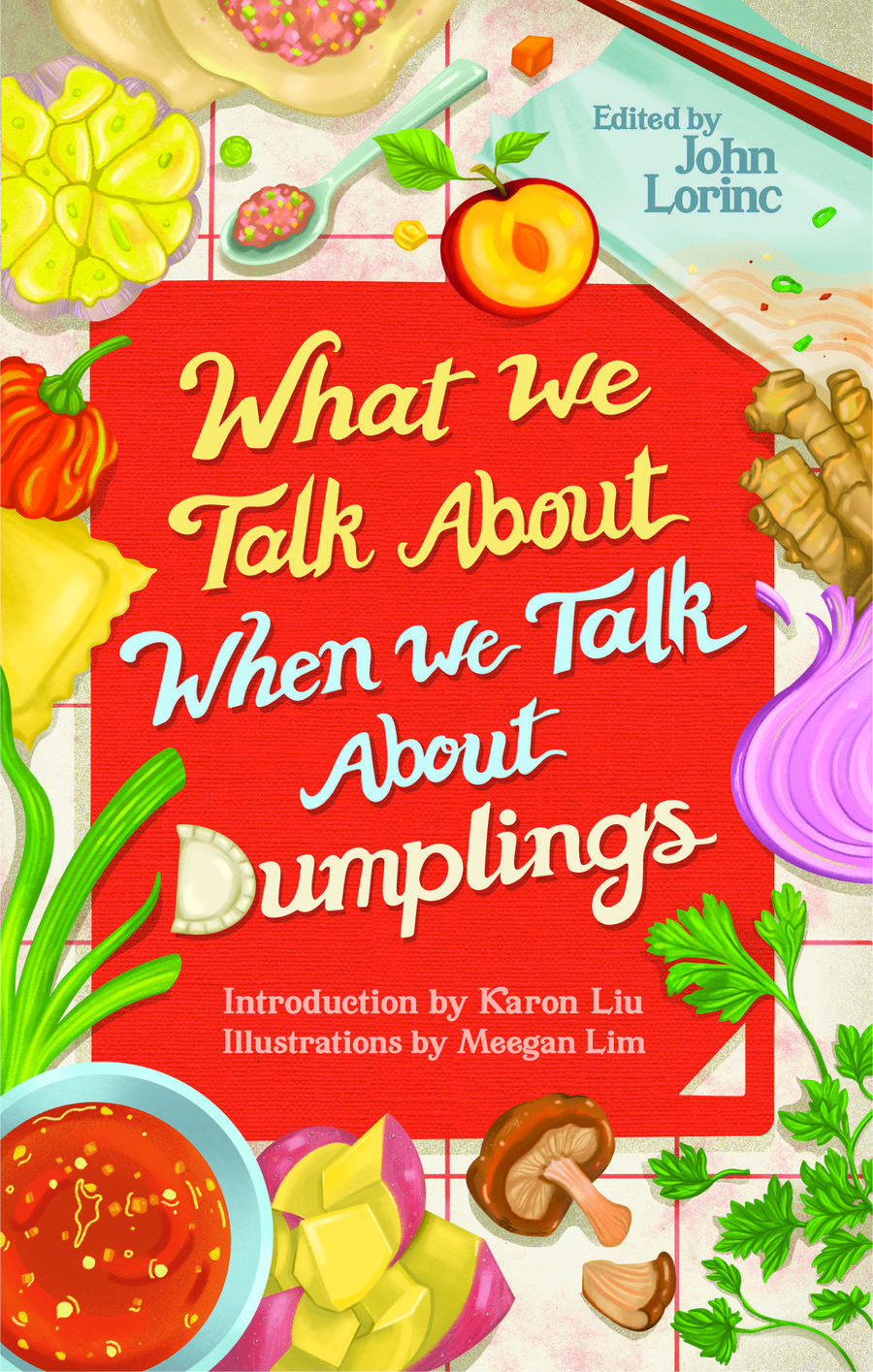

Excerpted from What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings, edited by John Lorinc. Published by Couch House Books. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Excerpted from What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings, edited by John Lorinc. Published by Couch House Books. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.When chef Angela Dimayuga published Filipinx: Heritage Recipes from the Diaspora, in late 2021, her recipe for siopao was accompanied by a story from her childhood. Having grown up in a family of six children, she wrote about how she and her older siblings would sneak in through the back door of a fortune cookie factory in San Francisco’s Chinatown to watch the assembly line while her mom waited at the bakery to pick up baozi—“what we call siopao,” Dimayuga wrote. “We’d buy a dozen with fortunes and another dozen discards, broken cookies left flat and unfolded, just to eat alongside our [buns].”

Most Filipinos, both in the Philippines and abroad, have memories of eating siopao as children. “I went through a phase as a kid where I only ate the filling,” wrote one food blogger, whose page I scoured for siopao-making tips. But ask even the most avid, non-Filipino restaurant goer and food enthusiast in my city, Toronto, or places like New York, Chicago, or Boston, and it’s likely they’ve never even heard the name—pronounced shoh-pao.

Why does a Chinese bun filled with a meat dish—originally inherited from Spain and sold frozen in plastic packs in the Little Manilas around the globe—exist mostly within the confines of Filipino homes and mouths?

In Tikim: Essays on Philippine Food and Culture, the late Filipino food historian Doreen Fernandez explained it best when she wrote, “Philippine foodways have been difficult even for Filipinos to understand, so variegated they are, coming as they do from different cultural strains. . . . When one asks today, therefore, ‘What is Philippine food?’ the answer can be neither brief nor simple.”

Siopao is hard to understand because Philippine food culture—forever changed by our history as a colony of both Spain and America—is hard to understand. This steamed dumpling, relatively unknown outside the Filipino community, tells the story of our history through its exact parts: the bun—Chinese ties; the filling—Spanish conquistadors; the means by which we eat it—American culture.

Siopao, in fact, might be the way that you and I can better understand Filipino food.

“Pinch, pinch, pinch,” I mumbled to myself after four already-failed siopaos unravelled before my eyes. I was hovering over the island in my kitchen, trying to be as present as possible. No one had told me that closing a dumpling required such focus. My husband looked over at me while reading a book to our son. He’d watched me slog all day over this dough. I’d spent the morning making two batches: the yeast hadn’t activated in the first one; the second was perfect. But siopao dough needs to proof three times over the course of a day. And, while I’m an avid home cook, I’m practically a dough virgin.

I’d never seen anyone make siopao by hand—not my late mamang (grandmother) or any of my titas (aunts) or my mom. I panic-messaged the Filipino chefs I follow on Instagram: Dennis Tay, chef de cuisine at DaiLo in Toronto, was the most helpful: “After the first mix, you should let the dough double in size while covered,” he wrote. “Then portion it and form it into balls, cover it, and let it double again. And then, after you’ve stuffed, folded, and closed them, you should let it proof again uncovered until the lines from the folds soften a little.”

I was out of my depth. The convenience of frozen siopao was something I’d enjoyed my entire life. The siopao I loved didn’t come from the hands of any matriarchs I knew personally, let alone from a bamboo steamer. It came out of a plastic box.

Most people won’t know that this commercialization is an American legacy. The story of siopao unfolds bit by bit through our history.

Alex Orquiza is a Filipino history professor and author of Taste of Control: Food and the Filipino Colonial Mentality under American Rule. He says American advertising for canned goods—and the attributes like ‘cheap, easy, healthy’ that marketers assigned to them—took hold in the Philippines in the 1920s and ’30s. It had been some thirty years since Spain ceded the islands to the United States, and America was profiting. By 1934, the Philippines was the largest market for US exports like cigarettes, soap, and canned milk and its ninth-largest export market overall.

The Philippine middle class in Manila welcomed the canned foods whose ads they saw in print and on their televisions. (In fact, Spam, a canned, cooked pork, is still considered a national favourite.) “Industrialized labour really takes off during that time period and is picked up again after World War II,” says Orquiza over the phone from Boston. “The fact that Magnolia brand exports [frozen siopao] so we can buy a pack of six here is along the same lines as [Philippine consumers] being ingrained into buying Del Monte canned fruit [from America].”

But, long before Americans brought industrialization to a primarily agrarian society, there were the conquistadors. Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese explorer, landed in the Philippines in 1521 and claimed it on behalf of Spain. In 1543, the territory was named “Felipinas” after the crown prince, Don Felipe of Spain, who would later become King Felipe II. The archipelago of over 7,100 islands later became known as Las Islas Felipinas. The anglicized version: the Philippines. Along with capturing a share of the spice trade in the resource-rich country, Spain’s mission was to convert Filipinos to Christianity and also to make connections with China and Japan in order to establish Christian missions there.

From 1565 to 1898, a Spanish colonial government—the friars—ruled the country. In his book A History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos, Luis H. Francia so accurately describes the way colonialists changed us evermore. (The word Indios was what the Spanish used to describe Philippine native peoples. José Rizal, hero of the Philippine nationalist movement, which began in 1863 and culminated in 1898 with the expulsion of Spain, borrowed the term to name his group of intellectuals the “Indios Bravos.”)

“In a sense we were [also] Indios Bravos ourselves,” Francia writes, describing himself and his writer friends in the 1960s, “not just intensely aware of but embodying the legacies of the Spanish and North Americans in our lives and ways of thinking, even in our blood—to be wrestled with, confronted, transformed, but not eliminated.”

In the ways in which Filipinos eat, the Spanish influence has not been eliminated but rather transformed. Pork asado braised—not grilled as the name intends—is a dish originating from Mexico (think: carne asada). In fact, the Spanish expedition to the Philippines from New Spain (Mexico) in 1565, to establish Spain’s first colonial government, was part of an effort to build a trade route carrying Chinese silks from the Philippines to Mexico while shuttling silver, missionaries, and soldiers back to the islands.

Chinese traders have been on the islands since the tenth century, importing Southeast Asian commodities like cotton, coconuts, and woven mats. Under Spain, they migrated in mass numbers from southern China’s coastal provinces, like Fujian, Amoy, and Guangdong, to work as craftsmen and artisans. Initially, Spain placed all of these siong lai (Hokkien for frequent visitors, or “sangleys,” using the Anglo term) in a Manila ghetto. In 1594, the Spanish governor encouraged cultural assimilation among the sangleys who had converted to Christianity, and they were moved to Manila’s Binondo area, now known as the oldest Chinatown in the world.

As University of Southern California associate professor Adrian De Leon, a Filipino Canadian, writes in his 2016 essay “Siopao and Power: The Place of Pork Buns in Manila’s Chinese History,” the Spanish view of the Chinese was that they were entrepreneurs and capitalists, but they remained the perpetual “other.” “By the 19th century, the Chinese mestizo [descendants of sangley Chinese and native Filipinos, which included José Rizal] exerted influence on public affairs. The Spanish administration, seeing this as a threat, sought to turn the natives against the Chinese middle class to dispel anti-Spanish tensions,” De Leon writes. “These attempts failed. . . . By the end of the Spanish occupation, those with Chinese blood and those of native heritage were collectively known as ‘Filipinos’ in the campaign for independence.”

Prevailing Chinese culture is woven into the lives and dishes of Filipinos: lumpia are rice paper–wrapped spring rolls; pancit, the Philippine national noodle dish, means something “quickly cooked” in Hokkien; while siopao literally translates to “hot bun.”

Like Filipino food, the story of siopao, as Doreen Fernandez said, can be neither brief nor simple.

At family gatherings, after I’d spent hours sprawled on my tummy, with my neck arched and my eyes dry from watching the television while we kids took turns playing Nintendo games, a flash of hunger would jolt through me, and I’d run downstairs. “There’s siopao,” my mom would say as she pulled apart the plastic hinged takeout container that housed six white buns. She’d plop one onto a plastic plate and put it in the microwave for forty-five seconds. I’d watch that plate go round and round until she pulled it out and peeled off the square parchment paper placed at the base of the siopao (a trick that prevented the bun from sticking). Cutting it in half to reveal the shiny brown sauce and the quartered, salted duck egg inside, she’d hand me a Sprite, and I’d march back upstairs. I could hardly wait until I had one free hand to take a bite.

Nicole Ponseca is the author of I Am a Filipino: And This Is How We Cook and the restaurateur behind New York City’s Jeepney and the now-closed Maharlika, one of Manhattan’s first modern Filipino restaurants. She says eating siopao is just like eating a Kit Kat in Kourtney Kardashian’s famed “Six Steps to Eating a Kit Kat” clip from Keeping Up with the Kardashians: everyone has a particular way they do it.

“My mother would rip the paper off the bottom, then gently peel the thin skin around the siopao that is formed when steaming—it was a very thin, imperceptible crust,” Ponseca says. “I adopted my mom’s way of eating it, because you can sink your teeth into the gummy bread. The way people eat it shows me who knows siopao.”

This ubiquitous Filipino steamed dumpling, which one can find frozen in packs of six at any Filipino-run store in North America, is more than the sum of its parts: its Chinese-inherited bun, its meat filling with a Spanish name. One bun tells the story of our history as Filipinos—through conquest, commerce, and culture—and it will never be brief or simple. One thing is for sure: siopao is not just for kids.