1: DAAKU

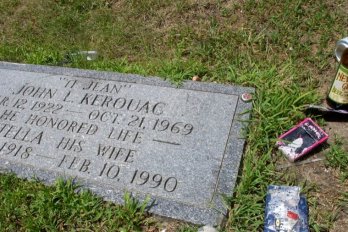

There was a notable book launch in the city of Surrey, British Columbia, in the spring of 2006. It heralded the publication of the novel Daaku, by a thirty-year-old writer named Ranj Dhaliwal. The book—about early-’90s Indo-Canadian gang activity in Surrey and Vancouver—is arguably an important novel, although the literary establishment wasn’t on hand to help celebrate.

Of course, the launch was a little off the beaten track by CanLit standards. It wasn’t held in a bookstore or independent coffee shop, but at Central City, a mega-pub in the Surrey Central Mall. And the crowd, too, would have been unfamiliar to many book launch veterans: a demographically sexy batch of young people, numbering nearly a hundred. Yes indeed, people in their twenties. And not a bookish crowd either. More gold chains and ball caps, more short skirts. More tuners and suvs in the parking lot. Certainly more of a police presence. And when the author finally arrived, he was surrounded by bodyguards. Not the sort of thing you’d expect to see at your typical Michael Ondaatje reading.

Dhaliwal may or may not have needed the security. He’s a big man: six feet two and 215 pounds, a devoutly observant Sikh with a blue turban and a chest-length beard, proficient at a joint-dislocating style of Brazilian jiu-jitsu. But he chose to have six biker friends accompany him that day because, as he tells me calmly, exuding the gravitas of the faith into which he was officially initiated in December 2007, “nobody has ever published a book like this before. And you just never know, right? ”

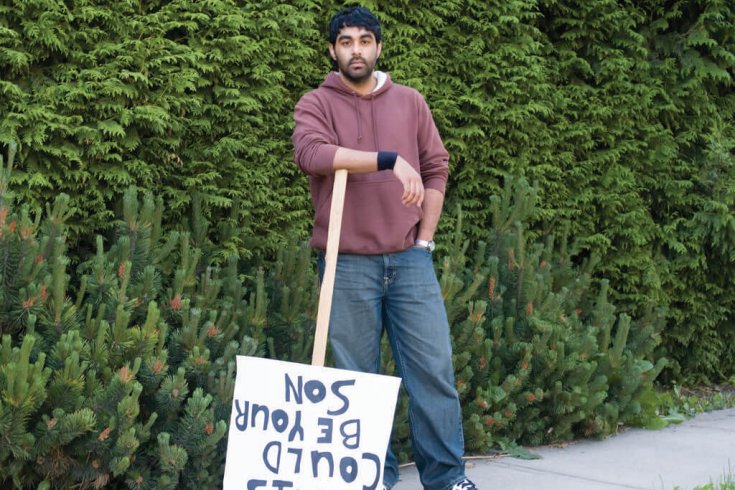

You just never know, that is, if you’ve written a fictionalized account of a gangster—a daaku (“outlaw” in Punjabi). In case you’ve missed it, over the past year or so gangsters in Vancouver and Surrey have been tragically newsworthy. Forty-eight dead this year, at the time of writing, and many more over the past decade. In the staggering closing sequence from filmmaker Mani Amar’s recently debuted A Warrior’s Religion, Amar holds up the names of all the Indo-Asian youth killed in gang violence since the early ’90s, each printed on its own large white card. At about 100 cards, you can see Amar’s arms droop with fatigue. And on the last four, he has written, I pray I never / …have to write your name / …here. / Peace.

Amar, like Dhaliwal, is from the community. But his enactment of the death toll captures the effect the news has had lately on outsiders, too. People showing up dead in their cars or alongside major thoroughfares week after week suggests a senseless frenzy, as if some orderly cycle of gangster reprisal has spun out of its groove and now cannot be stopped. When I talked to Vancouver detective constable Doug Spencer, who has worked on gang files since the mid-’90s, he said, “We’re seeing shootings now that are just completely paranoid. These guys are shooting people they don’t even have to.”

Given all the media attention on gangs, it’s no surprise that Dhaliwal’s publisher, New Star Books, is playing down the literary merits of Daaku in favour of its real-world authenticity. Publisher Rolf Maurer tells me, “Well, you know, Ranj isn’t Henry James.” Maybe not, but he may remind some readers of S. E. Hinton, whose 1967 novel, The Outsiders, achieved a similarly skilful blend of what’s thrilling and what’s good for you. Daaku’s depiction of gang culture is moderated by a restrained moral voice advising the reader not to get involved. But Maurer knows what sells. So he’s pitching the insider angle, playing up an unsubtle suggestion that at one point in Dhaliwal’s life, before the turban and beard, before his full initiation into Sikhism, he may have been a daaku himself. “Oh yeah,” Maurer says to me, “Ranj knew Bindy Johal growing up. They were gym buddies.” (Johal was one of the most powerful Lower Mainland gangsters in the mid-’90s. He was killed on the orders of his trusted lieutenant Bal Buttar in December 1998.)

Dhaliwal may or may not have hung out with bad guys. He certainly cared enough about authenticity to research the wholesale price of marijuana for the book and confirm various other details through “friends of friends.” But given that the novelist now spends his off-hours talking to school kids about the perils of crime, his book is better seen as an attempt to bring about change in the Lower Mainland’s Sikh community. For some, he has come to represent a possible future. Here is someone whom colleagues describe as a “sharp dresser,” who once drove a leased white SUV, but now espouses the egalitarian and ecumenical ideals of his faith. A man who is committed to social justice and the environment (he works by day as a paralegal for Ecojustice, formerly the Sierra Legal Defence Fund), whose identity is yet embedded in a conservative interpretation of Sikhism. “My whole thing is to get kids out of gangs and off drugs,” Dhaliwal tells me. “But we need to educate our own community about their religion first.”

2: VISIONS OF THE GURDWARA

What people attending the Daaku launch at Central City that night wouldn’t have known is that Ranj Dhaliwal was on his way to becoming—in addition to an important writer from the area—an important elected community leader. In the fall of 2008, the author was asked to join a slate of young candidates running for the leadership of one of the largest temples in the Lower Mainland: the Guru Nanak Gurdwara, on Scott Road in Surrey. That election contest would prove to be a protracted and litigious battle between two visions of what the temple should represent in the Sikh community.

Outsiders with Christian church backgrounds might underestimate the importance of this election. But temple committees are more than vestries. Their members assume responsibility for independent non-profit organizations that can control significant real estate assets and annual revenues from the donation box running into the millions of dollars. Temple leaders are also important political power brokers. Committees can’t tell their congregations how to vote, but individual committee members often endorse federal and provincial candidates. Ask Ujjal Dosanjh how significant it was that Balwant Gill, president of the Scott Road temple, failed to endorse him during the 2008 federal election for Vancouver South. Dosanjh won the long-time Liberal riding only after a recount, and then by just twenty votes.

The most important role the temples have played in Sikh life historically, however, is as sites of social and cultural security for new Canadians. The country’s first gurdwara was built by the Khalsa Diwan Society in Vancouver in 1908, in the heart of Kitsilano. The temple was open to anybody at that time—Indians of all castes were welcome, for example—in keeping with the teachings of Guru Nanak Dev Ji (1469–1539), the first of ten Sikh gurus who established the doctrine that all races, religions, and genders should be considered equal, and that a true Sikh should not discriminate against anyone. Even so, the sense of displacement for new arrivals, who often came from small farms in the Punjab, would have been radical. In Sarjeet Singh Jagpal’s 1994 book, Becoming Canadians, the oldest surviving members of the community recalled the earliest days: Men having to pantomime in order to buy eggs, all of them dancing around, flapping their arms and squawking like chickens. A woman screaming in surprise the first time she saw a Chinese person—and the Chinese person screaming back. “Coming here would have been like you and me going to the moon,” says Jagpal, whose grandfather arrived in 1907.

Local racism further isolated new arrivals. In 1907, Vancouver’s notorious race riots broke out, led by the candidly named Asiatic Exclusion League. Four decades later, Jagpal’s mother was blocked by residents when she tried to buy a $6,000 house in Kelowna on which she’d already put down a deposit of several thousand dollars. She took the matter to city council, where it was debated for weeks before the sale was approved. The Kelowna Courier’s top story for August 22, 1946, recaptures the priggish ignorance of the day:

Local residents… are protesting over the contemplated purchase of a house on Wolseley Avenue by a Hindu family on the grounds… that the area would slowly grow into a Hindu settlement, thereby lowering property values and causing general unpleasantness in the neighborhood.

The size of the deposit suggests another “Hindu” quality that might have alarmed white, middle-class Kelowna: intense industry and thrift. Hard labour was the order of the day for most Sikhs. Men often worked twelve-hour days at the most back-breaking job in the province’s sawmills: the dreaded green chain, stacking fresh-cut lumber before it fell off the conveyor belt.

“These guys had to be tough,” says Jagpal, who worked the green chain himself decades later, while attending university to become a teacher. Against that backdrop, he explains, the temple became a critical place for regrouping and gathering one’s strength. “They went through a lot of crap together. And the only way to handle it was to get together on the weekend at the temple, compare stories, blow off a bit of steam, pat each other on the back, and say, ‘Well, at least we have each other; we’re like family.’ Then get back out there and work six days again.”

The temples have of course evolved over time, alongside the community. A dramatic example was the transformation of Vancouver- and Surrey-area temples in the wake of Operation Blue Star, the tragic storming of the Golden Temple in Amritsar by the Indian military in June 1984. Following that came several other high-profile events: The reprisal assassination of Indira Gandhi in October. The anti-Sikh riots in Delhi in November. And then the bombing of Air India Flight 182 in June of the following year.

The impact of these incidents on the local community was “visible and immediate,” in the words of Hugh Johnston, professor emeritus of history at Simon Fraser University and co-author of the 1995 book The Four Quarters of the Night: The Life-Journey of an Emigrant Sikh. He describes to me how, after Operation Blue Star, many Sikh men began to adopt traditional markers of the faith: turbans, beards, the kirpan knife and kara iron bracelet. “It was a collective shock,” he says, “and it gave birth to a tremendous sense of threat.”

That threat also contributed to a surge in support for an independent Sikh state called Khalistan. Although most Sikhs did not embrace the separatist cause, according to The Sikh Diaspora in Vancouver, by Kwantlen Polytechnic University instructor Kamala Elizabeth Nayar, “The popularity of this movement was evidenced in the growth of several organizations in Vancouver, which held as their single-minded goal the establishment of a separate Sikh homeland.”

Nayar mentions two particularly significant organizations, the Babbar Khalsa International and the International Sikh Youth Federation, both started in the ’80s and listed as terrorist entities by Parliament in 2003. The prime suspects in the Air India bombing were members of Babbar Khalsa International. And the ISYF grew in influence to the point that it was able to take over control of some of the largest and most important gurdwaras in the Lower Mainland.

The ISYF, whose members typically dressed in the orthodox style, took over the Scott Road temple in 1986, and held power for over a decade. But there were concerns from the start about their leadership. Prominent Vancouver businessman Harpal Singh Nagra, a founding member of the ISYF in Canada and author of the group’s constitution, quit outright in May 1986, the day after four ISYF members tried to assassinate the Punjabi planning minister on Vancouver Island. “I told them, you did not follow the constitution. We do not accept any violent act here in Canada. That’s it.”

Nagra notes that the ISYF’s initial support rested on the community’s belief that it was best suited to fighting for Sikh and human rights. “But that didn’t happen,” he says. “People were given the wrong idea. And by then [ISYF members] had gained control of most of the temples and were using their funds for their causes. Wherever they wanted to promote the cause of Khalistan, they had discretion. They had full power.”

Members began to leave the ISYF-controlled gurdwaras. “Many families pulled out of [temples] controlled by Khalistani leadership,” Hugh Johnston says. “They didn’t feel comfortable there.” Others stayed, he says, but kept quiet.

The ISYF era at the Scott Road temple ended in 1998, when a coalition of conservative and liberal Sikhs won the temple by 250 votes at the first election held since the ISYF came to power. The election was contentious, to say the least. At one point before the vote, Harpal Nagra—who helped pick the candidates opposing the ISYF, including Balwant Gill, the incoming president—was attacked with a sword. The best-known element of the conflict, though, was the notorious “tables and chairs” controversy, which hinged on the question of whether the communal langar meal—a traditional Sikh practice emphasizing the equality of participants—should be taken sitting on the floor, or whether members could be permitted to sit at tables, on chairs.

Tables and chairs had always been tolerated in the gurdwaras, dating back to the establishment of the Khalsa Diwan Society in 1906. The original Sikhs in Vancouver typically wore Western dress, no doubt to forestall the magnified discrimination they would have otherwise faced from locals. And there was simply no way for a Sikh woman to sit politely on the floor in a Western dress. Add to that the sketchy central heating of the day and the fact that Vancouver streets were a notorious mud bowl, and tables and chairs might have been the only way for Sikhs to preserve the langar tradition in the region.

Despite that history, and despite the fact that while they controlled the temples the ISYF leadership had never previously thought to remove the tables and chairs, the issue became a flashpoint shortly after their narrow electoral defeat. According to Nayar’s timeline, the ISYF was voted out in January 1998. And in April 1998—some say after ISYF agitation—the senior Sikh religious governing body, the Akal Takht in Amritsar, issued a formal edict against the use of tables and chairs.

The Scott Road temple management committee, and at least two others in the Lower Mainland, failed to conform to that edict. And again, some congregation members left to start their own temples. But more important, a division formed between notional categories of Sikhs in British Columbia—categories that had never been a factor in the past, and which were no doubt entrenched by media coverage shaping the terms of debate. On one side were “fundamentalist,” “traditionalist,” “orthodox” Sikhs—thinly veiled code words for “Khalistani,” whether the people being described believed in the cause or not. On the other side were “moderates.”

The election at the Scott Road temple on November 23, 2008, must be considered against that divide. After ten years of rule by Balwant Gill, and more than twenty years since the Air India attack, the “moderates” were at last unseated. By a youth slate, no less, most of its candidates under the age of thirty-five and quintessentially of the twenty-first century: president-elect Amardeep Singh Deol, a software engineer; vice-president-elect Ranj Dhaliwal, an environmental activist and author. All of them adhering to the panj-kakaar observances of their faith: all wearing turbans and the traditional kirpan and kara, and all the men bearded. All, as the press and the defeated parties had it, “fundamentalists,” “traditionalists,” “orthodox.”

And amid all the coverage, a single question seemed to lie in the subtext: how on earth did this happen?

3: A WARRIOR’S RELIGION

Mani Amar’s documentary, A Warrior’s Religion, didn’t set out to answer this question. But by addressing head-on the role of gurdwaras in the community, his film throws light on a prevailing mood in the Sikh community, and therefore the electoral result.

Amar is twenty-seven years old. I meet him in his home studio, where he cut together the movie he had more or less single-handedly written and shot over three years. He’s in T-shirt, jeans, and a frayed ball cap, looking antsy because game seven between the Detroit Red Wings and the Anaheim Ducks is due to begin in just over an hour. There’s Red Wings insignia throughout the room, nunchaku and other martial arts weapons hanging on one wall, and Ganesh and Lakshmi statuettes perched high on a wall sconce.

“My manager gave me those to help me prosper by staying out of debt,” Amar says. “I don’t care if you believe in Allah or Christ or the Dalai Lama; as long as you’re doing good in the world, I’ll see you in the end. And I don’t care if you shave your head or if you’re circumcised. I just don’t give a fuck.”

Pause. Then: “Sorry for swearing. I’m a total island boy.”

Vancouver Island, that is. Amar was born and raised in Port Alberni, in the interior of the island, and moved to the Lower Mainland nine years ago. He still fondly remembers small-town life, including one of the famous bush parties he attended, although he’s never had a sip of alcohol in his life. But it’s quickly apparent Amar doesn’t pine for safe and stable patterns. He’s all about change. The phrase “making a difference” comes up a dozen times in our conversation. As in: “I was the sixth grader fighting for the recycling program at school. The kid writing articles, trying to make a difference.”

Tellingly, his film opens with a quote from the Talmud: “Whoever destroys a soul, it is considered as if he destroyed an entire world. And whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world.” This is a call to activism, Amar says. A call to reject consumerism’s core value “that the more you have the more you are,” which leads to young people “forgetting their God-given abilities… the ways in which they really could make a difference.”

Amar wanted his film to get the community talking about why well-off kids are dealing drugs and shooting each other in drive-bys. And the film has had this effect. Thousands of people have shown up for early screenings. Lots of local press. By the time I speak to him, Amar has already fielded a request to discuss gang issues with the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights.

The film covers a lot of territory, in interviews with IndoCanadians from then BC Supreme Court Justice Wally Oppal, to former chief constable Kash Heed, to grieving mothers who’ve lost kids, to gangbangers both active and retired. And while the gang issue is massive and multivariate, with each relevant factor he raises—whether lingering racism, Indo-Canadian family dynamics, or something else—Amar holds out hope that, through discussion, opportunities for positive change can be found.

There are no easy answers. Amar may criticize an Indo-Canadian tendency to minimize family problems to save face, but he’s also quick to tell me, “That whole mainstream idea about Indian parenting being old and backward is bullshit.” The underlying issue is the adaptation of a communal Indian parenting style, dependent on multiple generations, to the fast-paced, individualistic Western life. And for that adaptation to be successful, education and coaching is required, either from temples or the broader community.

On the influence of the Sikh religion, Amar navigates similarly tricky waters. Does the history of Sikh martyrdom contribute to the gangster mindset? The bad guys in the film all seem to think so, including Bal Buttar, who was himself shot and left paraplegic after arranging Bindy Johal’s death. But Amar doesn’t buy the excuse, nor do most of his interview subjects. As Kash Heed says in the film, thousands of kids learn about Sikh history every year and don’t join gangs.

Where Amar takes a harder line—and raises matters relevant to the November 2008 election—is on the role temples have played in contributing to an atmosphere in which gangs have sprung up. Specifically, he’s critical of the lack of programming, such as alcohol or domestic abuse counselling, to address problems that feed into gang violence. That lack is precisely the reason Ranj Dhaliwal decided to run for office himself.

Both men, from their respective liberal and conservative perspectives, praise the innovative work of one gurdwara in New Westminster, a temple run by another young group of devout, observant Sikhs. Among this temple’s initiatives are courses on subjects like parenting, and translating Gurmukhi texts and Punjabi services into English, both of which encourage the younger generation to plug into the faith and provide them with a sense of community that might forestall the appeal of gangs. As Amar says to me, “Those guys in New West are cutting edge in the Sikh world.”

Though his film points out that crime is a societal problem, and that temples can’t be held responsible for solving crime in neighborhoods that happen to have large Sikh populations, he continually comes back to the question of what the temples might have done over the past twenty years to foster an atmosphere of cynicism toward authority, which might in turn have contributed to the influence of gangs on young people. His critique is twofold, aimed at two very different eras of temple leadership. Regarding the current “moderate” temple leaders, Amar holds—in person and in the film—that “everybody knows” leaders who have used their positions for personal gain, and therefore “lead by bad example.” He tells me of temple officials who have fancier cars and bigger houses after a year in office.

Suspecting an ulterior personal motive is one thing. But the suspicions expressed by Amar and Dhaliwal of the leadership in a previous era fall into a different category. Dhaliwal’s novel, so meticulously researched, is set in “the time of the original Indo-Canadian gangsters,” during the early-’90s ISYF days, when such gangland figures as Bindy Johal and the Dosanjh brothers (Ron and Jimmy, both active ISYF members) were regulars on the nightly news. Notably, a central narrative turn in the novel comes when temple officials (“the old religious guys”) hire a soon-to-be gangster named Ruby to beat up a political rival. When I ask Dhaliwal if that’s pure fiction or whether it represents what young people believed in the early ’90s, he answers flatly, “Yes, that’s what they thought. Definitely. Oh, definitely.”

Amar heard similar stories from the gangsters he interviewed from that era. One of them, he says, described his earliest hits, for which he was paid $10,000, as being carried out for clients who were “religiously and politically motivated.”

The biggest shocker in A Warrior’s Religion, however, has to be the comment let slip by Detective Constable Doug Spencer of the Vancouver Police Department. On camera, he says to Amar, “I was actually rather disappointed with the temple when they were taking Bindy in and protecting him… He was keeping guns in there, and it all came out in the media. And I was surprised that [the temple] didn’t ostracize him.”

Only it hadn’t all come out in the media. Spencer later confirmed with me, though, that the VPD had a warrant to remove guns from a temple in the mid-’90s, and that informants told him at the time that the weapons were being held for Johal. Amar says he checked out the story independently with former members of Johal’s crew, who said the gangster had been hiding “a lot of stuff” in a particular temple. But these sources declined to go on the record.

The critical point here for those seeking election in November 2008, however, is that this story, true or not (the police never laid charges), speaks to a lingering speculation about gang-related temple corruption during the late ISYF era. And that in turn may well have contributed to people’s willingness to question the motives of leaders, even today. All of which was highly relevant to those heading to the polls.

4: IT’S NOT OVER ’TIL IT’S OVER

The youth slate won the election on November 23, 2008. Deol and his eighteen-member committee prevailed by a margin of 1,153 votes, taking 41 percent of the 14,594 ballots cast. But the victory was narrower than the numbers suggest. In fact, the youth candidates might very well have lost had not the “moderate” group led by Balwant Gill split into two parties, the other led by Sadhu Singh Samra, in the wake of a year of court challenges on technical matters relating to voter registration. Not even the resurrection of the tables and chairs debate (more peaceably this time) could keep the two factions united. Nor could Gill’s and Samra’s breathless assertions that the youth slate were “Khalistanis,” which may be the scariest thing the two moderates could think to say about them, but is not a charge insiders especially buy. So the youth slate went to the polls with an underdog’s dream scenario: an opponent divided. Yet, seven months later, they were still not in office. And they won’t take office unless they manage to win a new, court-ordered election scheduled for November 2009.

According to Gill, whom I met at the Scott Road temple, the new election stemmed from a disagreement about two weeks. After the first vote, Gill conceded and agreed to hand over the temple on January 1, 2009. But the youth candidates demanded that the transfer take place December 8, fifteen days after the election, as stipulated in the temple bylaws. Gill says he would have ultimately agreed to the earlier transfer date, but only if the youth slate would agree to a term expiry date of December 8, 2011—i.e., three years to the day later. But here the youth slate decided to resist, insisting their term run until January 1, 2012.

So the parties went to court, again, by my count the seventh time some combination of Gill, Samra, and the youth slate had appeared before BC Supreme Court Justice Bill Smart in two years. During this latest application, it came to light that there were irregularities on the youth slate nomination forms. Balwant Gill, it seems, had gotten to wondering about the group’s haste to take office. “I thought, ‘What’s the rush? ’ It created a doubt. I thought, ‘Something must be wrong.’”

Something was wrong. Of the eighteen newly elected committee members, none had been nominated properly.

Among the twenty-five required signatures on each of their forms, there were duplications, some that didn’t match sample signatures on file, repeated signatures, and evidence that people had signed on behalf of others. The society filed an application to annul the election. And back it all went to court. In his ruling, Justice Smart explained that he couldn’t annul or validate the election without another trial—the cost of which, he noted tartly, would hopefully be “less than anticipated.” Or they could send the whole matter back to the polls. And on that suggestion, all sides finally agreed.

Socially progressive religious conservative Ranj Dhaliwal won’t be running, however, having resigned from the youth slate. He’d signed on for the job believing the matter would be settled within a few months, not a year and half. “It’s just sad that a temple election has to go to court,” he tells me. “It’s like these guys are trying to be prime minister or something. I just wanted to get religion back into the temple.”

As for socially progressive religious liberal Mani Amar, a career in politics is unlikely to tempt him. He tells me, “I’m not big on being known. I’m just big on getting something done.” And on that note, his mom brings in hot tea and a platter of samosas with chutney. It’s time to eat and watch some hockey. Talk of politics and religion must wait for another time.