If you’re anything like me, you might have felt your cheeks start to burn and your heartbeat quicken as you stepped into the pink glow on the sidewalk outside 2200 Dundas Street East, in Mississauga, Ontario. Looking up, you’d come face-to-face with Iris, the forty-four-year-old mannequin, standing silently in the window. Her close-cropped, airbrushed plastic hair and voluminous vinyl eyelashes would likely be the second thing you’d notice after her feathered crimson brazier and matching crotchless thong. Her outstretched hand usually held several silicone vibrators or, sometimes, a butt plug. Next to her, the word “Lovecraft” hummed in red neon. Inside the small shop, Pepto-Bismol pink walls and fading silk flower arrangements surrounded an enormous wooden phallus statue in a gilt triptych—part of an original Japanese Shinto shrine symbolizing fertility and sexual health. Facing the door was a neat arrangement of greeting cards, the kind you wouldn’t give to your grandmother.

In the centre of the floor, glass cases displayed a rainbow of girthy silicone phalluses. At the bottom of one case sat what looked like a steel impact drill but was, in fact, an antique “massager.” Farther in stood a wall of chains, ribbons, Velcro handcuffs, and whips, all dangling next to an arsenal of colourful oils, organic lubricants, jellies, and chocolate sauce. A trademark selection of dirty novelties included penis lollipops, gummy breasts, and “pin the macho on the man” posters. Another display featured sexual health accoutrements, including dilating toys that ranged in width from a modest centimetre to an impossible-looking two inches.

Standing near a family restaurant and an electronics-repair shop, this haven of sensual delights seemed strikingly out of place—especially to me. Barely five feet two inches tall and wearing a too-big dress shirt and braces, I looked more like a Catholic schoolchild lost on a field trip than the newest employee of Lovecraft sex shop. To make the situation stranger, the only other person in the store was my aunt Pamela, laughing quietly at me from behind a vintage cash register.

I grew up on a farm in Amaranth, Ontario, population 4,079. I was a goody-goody Christian nerd with no television and scarce internet access. In the tenth grade, someone told me what a dildo was, and I didn’t believe them. When I moved to Toronto, for university, I desperately needed a job but had little experience. My aunt Pamela, who owned a small shop just outside the city, tentatively offered me a sales position. I was nervous—and by nervous, I mean I was mortified and leagues out of my depth—but I did need the work.

At the time, my grasp of sex was shaky at best—I had seen breasts a few times, mostly by accident, and had kissed a total of two people. My parents gave me a vague “talk” when I was twelve and then barely spoke of it again. In my first and only high school sexual health class, I was told that abstinence was imperative and then shown some gruesome images of sexually transmitted infections. Now, I was supposed to be providing advanced, confidential sex advice to all manner of clientele. In my first week, I was told that I needed to possess an “encyclopedic theoretical knowledge” of everything Lovecraft sold—this was a joke, but I took it literally. The weekend after I was hired, I ignored my jackhammering heartbeat, wrapped myself in a blanket, and spent Saturday evening blitzing the entire supplier’s catalogue—complete with step-by-step written instructions, anatomical reference guides, and tips—and reading every clinical article and op-ed I could find on sex. By 5 a.m., I had learned that toys exist in every shape, size, and material, from plastic to diamond, rings to beavers, bullets to the ten-inch Man o’ War. I learned that alarmingly few men really know how to find the clitoris, let alone what it is. Most men have a prostate, and it can be stimulated. Kegel exercisers—silicon spheres intended for insertion—strengthen the pelvic floor, which can enhance sensitivity during intimacy. Always use lubricant (it’s not just for engines). You might know all of this already. I did not.

By the time I strolled into my Sunday morning shift, still wearing my church clothes (I’d attended a service earlier that morning), I was a different person than I’d been during my previous shift. I’d learned, among other things, that sex toys and paraphernalia are masterful works of craftsmanship and passion. I made my first sale—to an elderly woman who, upon entering the store, had stared at me with an expression that read, “Who left this little boy alone in this adult place?” She left carrying a plain, unassuming bag containing the Black Cherry Bullet (a tiny, two-inch starter vibrator), our finest organic lubricant, and a box of Lelo Hex condoms. I later had the opportunity to assist everyone from cancer survivors to LGBTQ couples to my high school classmate (who, yes, did recognize me and, no, had not known I worked there).

When I started, Lovecraft saw few daily walk-ins and was resigned to a crumbling Mississauga plaza on a tired stretch of Dundas Street. Today, its doors are closed, its energy focused instead on a revamped e-commerce website. Similar sex-positive shops have cropped up in Toronto over the years, some performing brilliantly and others not, but all promoting the idea that sexuality should be openly explained and explored. Working at Lovecraft obliterated and reconstructed my understanding of what sex meant to myself and others. Sex is an inextricable part of human life, contentious and wonderful and endlessly misunderstood, but it remains a taboo that we don’t talk enough about, and my own sex-ed absolutely suffered for it. In the same way that working at Lovecraft filled a fundamental gap in my understanding of sex, the shop helped open up a public conversation about sex and pleasure.

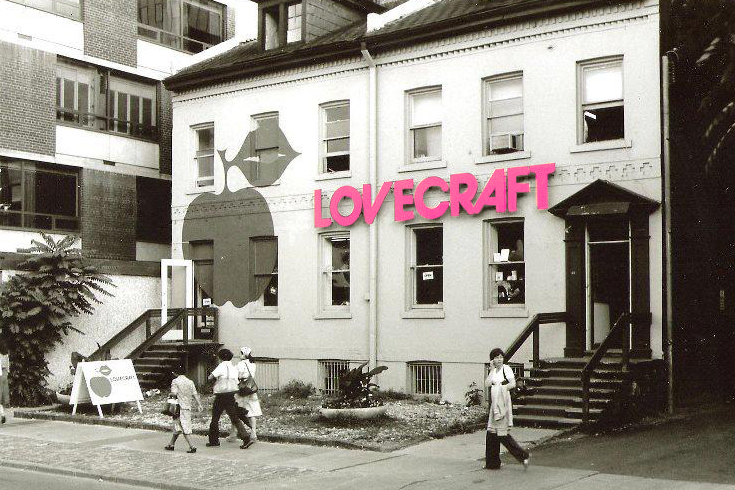

Lovecraft first opened, in Yorkville, in January 1972. Back then, the neighbourhood had no towering Louis Vuitton flagships or sky-puncturing condominiums—it was, as then Ontario Conservative MPP Syl Apps put it, “a festering sore in the middle of the city.” Yorkville in the 1960s was a glowing, smoky cesspool of youth, poetry, coffee houses, and nonconformity. It was a place, Neil Young would later sing, “where burnouts stub their toes on garbage pails.” Paddy wagons were regular fixtures on the corner of Hazelton and Yorkville Avenues. Drugs were easy to find, and creativity and sex abounded.

The following decade brought a gruesome end to the neighbourhood’s bohemian glory: in December 1971, a young woman, Marika Sokoloski, was found stabbed to death in her third-floor apartment at Rochdale College, the disintegrating hippie educational experiment that turned from an idealist school of free expression to a haven for drugs, communal mess, and failed leadership. Land deals peeled away Yorkville’s red-brick Victorian houses to build the 540-room Hyatt Regency high-rise hotel. Anne Amitay and Mary Sutherland saw the city changing and joined the new throng of Yorkville trend-seekers.

The Sutherlands had recently moved from the UK to Montreal for a job that Mary’s husband lost before they arrived. Mary met Anne Amitay at a Montreal dinner party—Amitay was a mother, twelve years Sutherland’s junior, teaching nursery school while her husband tried to make a living as an artist. The two women saw their situations reflected in each other and decided to work together to support their respective families. Lovecraft, then, was born not out of passion but necessity.

In an interview for her granddaughter Kate’s undergraduate thesis on Lovecraft, Sutherland said she had originally envisioned opening a store that sold equipment for children with special needs, but the startup costs were too high. While researching other options, she stumbled across Ann Summers—a chic white-walled sex-toy store in the UK. Stores like Ann Summers did not yet exist in Canada, their closest equivalents being what Amitay called “seedy head shops” and sleazy pornographic video dens. The idea of bringing a clinical, women-centric “marital aid” shop to Canada began to materialize. This was October 1970, not long after the Front de libération du Québec kidnapped Quebec labour and immigration minister Pierre Laporte and British trade commissioner James Cross, provoking the federal government to invoke the War Measures Act. In the midst of the crisis, the ethos of a sexual revolution hovered over Toronto and manifested in the city’s first women’s publishing houses, the first meetings of what would soon become the Pride Parade, and the sexual freedom of Yorkville. This energy convinced the entrepreneurs that Toronto was to be the home of their sex shop.

The pair spent days scouting location after location, recording patterns of foot traffic and shopping behaviours, looking for target customers. After fighting for a place to rent—no one wanted to rent to two women with no business experience selling “marital aids”—they landed a small storefront at 108 Yorkville Avenue.

“Brace Yourself,” warned a Toronto Star headline on January 14, 1972. “If you’re a staunch, Establishment Toronto matron who’s never been outside the country, yes, you’ll be shocked,” wrote Helen Worthington. “Don’t go into Lovecraft unless you’re prepared to have your eyebrows raised to an uncomfortable level.”

People filled the sidewalks, lining up for blocks. News spread across the country that Canada’s first approachable sex shop was open, and prospective customers packed themselves between the store’s clinical white walls. “It was pandemonium,” said Sutherland.

Shoppers were nervous—Amitay was repeatedly asked, “This goes where?”—but the crowd offered a sense of anonymity. The store’s target clientele was supposed to be professionals and married couples, but extensive media coverage pulled in people from all walks of life. “What’s the most popular toy?” was asked over and over. Women wanted to feel as if they weren’t alone in their interests. Men bought what they thought their wives might want.

For the first few days Lovecraft was open, the store saw a few timid customers alongside handfuls of young adventurous types. But soon, Lovecraft had sold out of its stock, down to the bare walls. Amitay’s husband, Johnny, drove in a frenzy to Montreal, in the middle of the night, to purchase the entire stock of The Garden, the only other comparable Canadian sex store, in order to catch up with the weekend’s demand.

But its popularity did not mean Lovecraft could suddenly slide into the blooming Toronto retail scene without difficulty. On November 24, 1972, Toronto police raided the boutique, seizing all merchandise and charging the store’s owners and manager with obscenity. The defendants were found not guilty on January 15, 1974, after proving that the store operated in the interest of the public good. The store was charged again with obscenity in 1977. No one in the Crown prosecutor’s office was interested in taking the case, and all charges were eventually dropped.

Sutherland told her granddaughter that she felt most customers treated Lovecraft as a gag gift tourist trap rather than a progressive, sex-positive shop. Tiny wind-up penises, edible underwear, and phallic straws were often top sellers. Men would hit on the staff and make filthy prank calls. While Lovecraft’s owners always refused to sell pornographic magazines or films, there was a hint of implicit vulgarity to the store’s early years. According to Sutherland’s interview with her granddaughter, people purchased gags because they felt uncomfortable buying what they or their partners really wanted. But, by the early ’80s, the sexual revolution was building to its peak, helped by the rise of second-wave feminism and the changing conversations around female sexuality and queer identity. Lovecraft’s clientele began to reflect these changes—and the ethos was spreading. In late 1977, Amitay and Sutherland moved the store to 63 Yorkville Avenue, more than doubling Lovecraft’s original size.

On her first day at Lovecraft, in June 1987, my aunt Pamela held a vibrator for the first time—a hard white plastic German cylinder with an unwieldy dial. An older female customer, imposing in high heels, had asked her what was popular. The vibrator took two C batteries, and Pamela had to work hard to hide her surprise when she demonstrated its top speed. Both women’s eyebrows raised slightly, the excitement of the unknown flickering between them. She made the sale.

Like mine, Pamela’s Christian upbringing had ensured scant knowledge of sex toys, so she felt like a fraud at first. But, as I later would, she quickly became enamoured with the store and her coworkers. She learned of Lovecraft’s “regulars” and was introduced to the prank callers—one man called a few times a week for more than a decade to ask if they carried the Beaver vibrator until, one day, the calls stopped. (He never bought it.) The customers even had nicknames: Micropenis Man was always disclosing facts about his allegedly miniscule member over the phone. Crotchless Panty Man would buy several of his eponymous item every time they restocked. Pig Soap Man carried an old-fashioned briefcase and would buy all of Lovecraft’s locally made pink pig soaps. For over twenty years, he came in and emptied the store’s soap stock after each refill, sometimes leaving a few in Iris’s plastic hand. One lady would always try to taste all the flavoured lotions. But, for every outlandish person that entered, there were ten more discreet people, so often asking, “Which one does everyone else get?”

Much of Pamela’s work involved helping people understand that sexual education, exploration, and self-focused pleasure are acceptable and normal. One woman in her seventies entered the store dressed head-to-toe in beige and told Pamela that she had lost her husband some months ago. After some gentle prying, she admitted that she had never had an orgasm. Several hours later, the lady trotted out with a bag of toys and a grin like a child on Christmas. Pamela would later give covert talks to mom groups in the basement of Leaside Church and other churches around Toronto. She’d lug in a shopping cart of wares, making sure every toy was charged up. Sometimes, the ladies would get all giggly and she’d have to wait like a schoolteacher until they quieted down. These women often returned as customers. “All they needed,” Pamela maintains, “was someone who listened to their needs.”

The store underwent another move, in 2000, from 63 to 27 Yorkville, and shifted back toward its original, more practical sensibilities. The wind-up penises were put in storage, though Lovecraft did stock up on Vibratex Rabbit Pearls following the famous Sex and the City episode in which Kristin Davis’s Charlotte York cancels plans to stay home with the dual-stimulating toy, which subsequently enjoyed a reported 700 percent worldwide sales increase. In 2002, Toronto Life claimed that the Lovecraft ethos—a knowledgeable, approachable staff and accessible displays—had established the sex-toy peddler’s gold standard in Canada.

According to Amitay, by the time the 27 Yorkville location’s lease ended, in 2010, rent had more than tripled since Lovecraft’s founding. Staff got leaner, stock thinned, and a Yorkville location became unsustainable. Instead, Amitay focused on the quiet Mississauga plaza that would become Lovecraft’s final physical location. Pamela bought the store from Amitay in 2014, two years before I began working there. I would be Lovecraft’s last sales employee.

The original Lovecraft location, at 108 Yorkville Avenue, is now a Brunello Cucinelli boutique, where you can find cashmere sweaters for $2,295 apiece. The 63 Yorkville address was flattened in the mid-’90s to build a high-rise condo. Rent at the building is $2,819 per month for a one-bedroom. The 27 Yorkville lot is a construction site slated to become another condominium in 2022. The shop at 2200 Dundas Street East is now a lighting-fixture store.

Early one morning in March 2018, generations of Lovecraft staff stood together, surrounded by barren Pepto-Bismol pink walls. It had been nearly fifty years since the store’s inception. The last pieces of stock sat in recycled boxes. The phallic shintai was sold to a long-time customer who requested it be saved the moment they learned the store would be closing forever. Iris the mannequin was picked up by an old colleague of Pamela’s, who uses her as a backyard art piece to this day. Rent was paid for the last time, and the storefront slipped quietly back into anonymity.