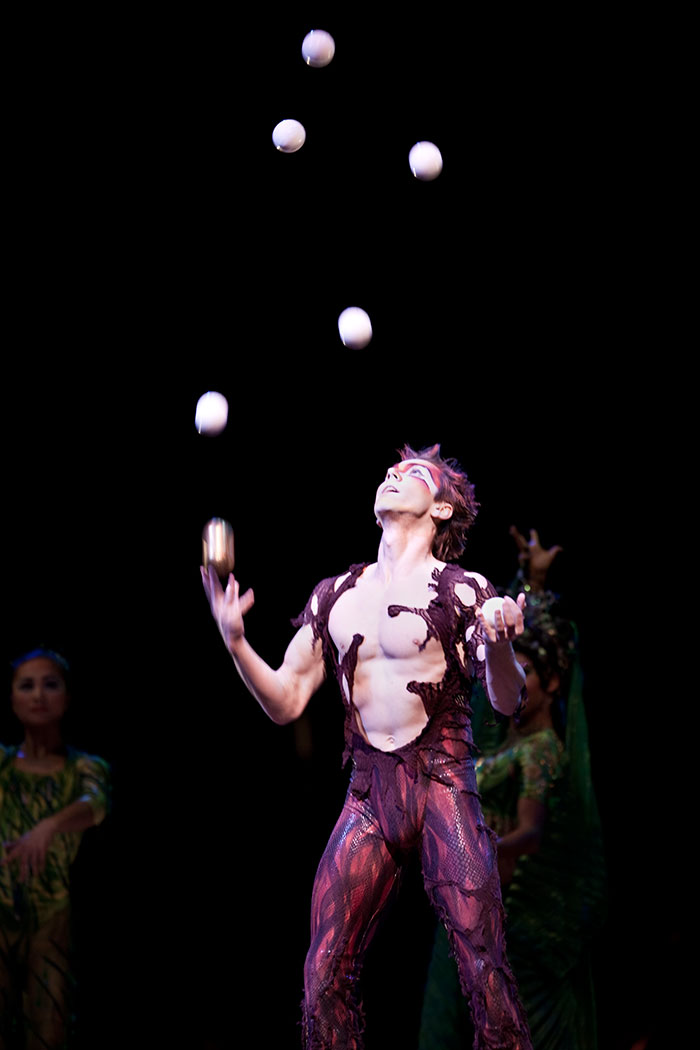

In a boxy complex built on a landfill in Montreal’s desolate north end, the future of the circus tumbles across the room. Tohu, the city’s $73-million circus development, looks nothing like a colourful big top strung with bunting and festooned with dazzling lights. Grey and silver, grim and industrial, it more closely resembles the campus of a powerful multinational corporation. But there’s no mistaking the students who somersault from trapezes, balance one handed, and dedicate up to thirty-eight hours a week to climbing, contorting, and swinging on the Russian bars at the National Circus School. These kids with shoulders the size of grapefruits and narrow dancers’ waists are not the runaways of Ringling, or misfits stowed away on caravan. Like pre-med students and would-be MBAs, they have excelled and trained and prepped. They study theatre, anatomy, and French. And they all know how to juggle.

In eight short years, Tohu has cemented Montreal’s reputation as the circus capital of the world, for better and worse. The school occupies one-third of the complex; to the west lies a performance space draped in black velvet; and in the middle sits the sprawling 394,000-square-foot headquarters of Cirque du Soleil, an entrepreneurial juggernaut that will generate at least $1 billion in 2012. Figuratively speaking, the company looms over Montreal’s entire circus world.

Montreal never was much of a city for travelling troupes. Even at the dawn of the Quiet Revolution, Quebec had only a handful of touring circus companies: the Shriners; the Russians; and Michel Gatien’s faux Italien Cirque Gatini, which came to an ignominious end after an elephant killed a trainer. The province simply has too few cities, situated too far apart, to support the year-round high-wire circuit found in France. And big tops don’t fare well in blizzards.

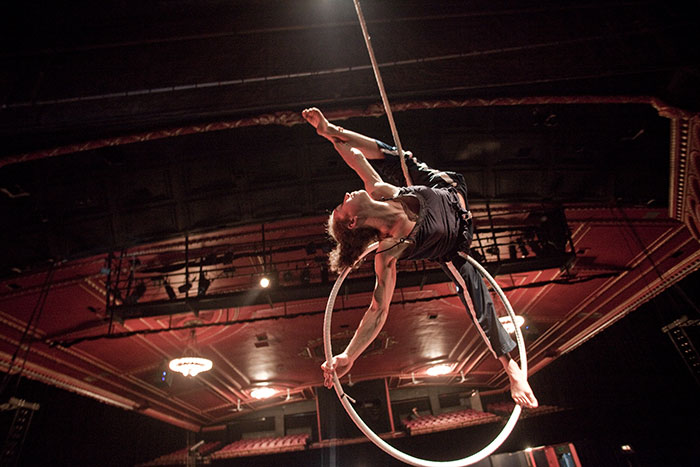

So instead of being born on the road, Quebec’s circuses were born in the streets. In the late ’70s, a booming busker scene emerged: clowns and acrobats who played summer festivals, jugglers who practised in La Fontaine Park. In 1981, street clown Guy Caron teamed up with Olympic gymnast Pierre Leclerc to open the National Circus School. From the start, the program emphasized technique (the school’s first home, the Centre Immaculée-Conception, also housed the Canadian national gymnastics team). But NCs‘s approach was artistic as well, and related to the work of groundbreaking locals, such as La La La Human Steps and the theatre company Carbone 14, which were also experimenting with the expressive potential of acrobatics.

Into this milieu wandered a fire breather called Guy Laliberté. He conceived of Cirque du Soleil in the village of Baie-Saint-Paul, five hours downstream from Montreal, where street performers and folk musicians often gathered. Cirque du Soleil’s first shows in 1984 combined Quebec’s irreverent busking sensibilities with Laliberté’s marketing savvy, and elements of nouveau cirque, a movement that had been percolating across the Atlantic for about a decade. French troupes like Cirque Bidon and Le Puits aux Images had reimagined the form without elephants and ringmasters, without the rote sawdust ritual, elevating entertainments into phantasmagorical, multidisciplinary art. It seems so obvious now, to take circus and give it story, characters, and feelings. To let tumbling and trapeze mingle with modern dance, commedia dell’arte, the pageantry of dreams. But it took Laliberté to sell it to LA, New York, and Las Vegas, and to transmute the form into a multimillion-dollar spectacle. As Cirque du Soleil’s fortunes (and its Montreal headquarters) grew, so did its gravitational pull, which attracted hundreds of starry-eyed acrobats, performers, and instructors. The NCS swelled to 150 students (one-third of them international), and new companies, such as Cirque Éloize (1993) and Les 7 doigts de la main (2002), landed like cannonballs on the world stage.

Montreal is a circus boom town, and yet for all the flash and dazzle some professionals worry that the city’s commercial success threatens its creative future. “The large circus companies can only take certain risks,” observes NCS artistic director Howard Richard, with a measure of wistfulness. “There is sometimes the feeling that you have to give back what the audience expects.” While his students study carefully crafted syllabuses (and are all but guaranteed a job, as 95 percent turn professional), the most innovative acts seem to be happening somewhere else, in Mexico, Argentina, even bourgeois Switzerland. There is little room for dreaming if every fantasy already seems realized, in a place where there is always a vast budget, exquisite technique, and another job waiting before you have even removed your makeup.

But the artists still remember what drew them under the lights: the risk, the thrill, the chance to brush up against another world. Experiments are once again taking place in the streets, in the metro—or even at Tohu, where management rents studios for as little as $2 an hour: a troupe called Recircle salvages equipment from the trash, while Cirque Alfonse reinvents the family circus with a show that turns Québécois stereotypes (sometimes literally) on their heads. Complètement Cirque, Montreal’s fledgling summer festival, brings together local acts and bold young turks from far away.

Perhaps the brightest sign for Montreal’s circus of tomorrow is Montrealers themselves. Three decades after Caron and Leclerc joined forces, an entire generation has grown up with the circus, on school trips and at day camps. A few kilometres and a world away from Tohu, shaggy-haired tightrope walkers gather on summer Sundays, stringing wires between Mount Royal’s trees. They’re just amateurs, tiptoeing up from picnic blankets and drum circles. But all professionals were amateurs once—until they stepped onto a tightrope, and stayed.

This appeared in the June 2012 issue and won an National Magazine Award