Adozen phone calls to government offices sounded the alarms last summer. They came from farmers, the acreage owner down the road, and residents in between. The city of Medicine Hat, Alberta, about fifty kilometres from the Saskatchewan border, was on high alert. There were rats in their midst, probably, maybe, they were pretty sure at least, but no one knew where they were coming from.

Sixty years ago, Alberta claimed rat-free status, just three years after the creatures first arrived. But reported sightings remain frequent: the Rat Patrol, made up of seven inspectors and seventy-three agricultural fieldworkers, receives up to 200 calls every year. Only a dozen or two turn out to be about rats, according to Phil Merrill, rat and pest specialist for Alberta’s Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. The rest are muskrats, gophers, ground squirrels, or even cats.

Still, Merrill takes every incident seriously. He plotted the locations of the reported sightings near Medicine Hat on a map. Smack in the middle sat the local dump. After two unsuccessful visits, the patrol finally dug up the culprits—151 all told—from beneath a heap of garbage. It was one of the biggest infestations they had uncovered in ten years.

Originally from northern China, these notorious stowaways have come to inhabit every continent except Antarctica. Blamed for spreading the Black Death throughout Europe and Asia (a theory that has since been disputed), brown rats are ruthless in their destruction of agricultural property—gnawing through floors, walls, and insulation to get at food supplies and harvests, and soiling five to ten times more grain than they actually eat—potentially causing billions of dollars of damage each year in farming areas worldwide. The economic fallout is exacerbated by the rate at which rats reproduce: one pair can spawn 15,000 descendants in a year.

Rats arrived on the east coast of North America around 1775 aboard European ships, reaching Alberta 175 years later. The province’s eastern border is the only way in: the Rocky Mountains are too high, the southern border too sparsely populated (not enough food or shelter), and the northern border, up at the sixtieth parallel, too heavily forested.

Fear and Loathing

When folklore is used for propaganda

Andrea Wan

The word “Rattenkönig” originally referred to one who lives well on the backs of his fellows, but Germans have long been inculcated with a fear of its more literal meaning: a folkloric monstrosity known as the “rat king.” This refers to a purported phenomenon that occurs when dozens of rats’ tails become entangled, the knot solidified with dirt, feces, fur, and blood, while a greater rat reigns over the writhing mass. A few specimens, on display in German museums, may be dubious in provenance, but this has not prevented rhetoricians from appropriating the image for political ends. Martin Luther called Pope Leo X “the king of the rats,” characterizing cardinals as “that rabble of rats,” monasteries as “rats’ nests,” and Münster’s Anabaptist theocracy as “a rats’ kingdom.” Although not strictly considered “fakelore” (a printed text masquerading as an oral tradition), the rat king persists as one of Luther’s most retold anti-Catholic tropes.

—Simon Bredin

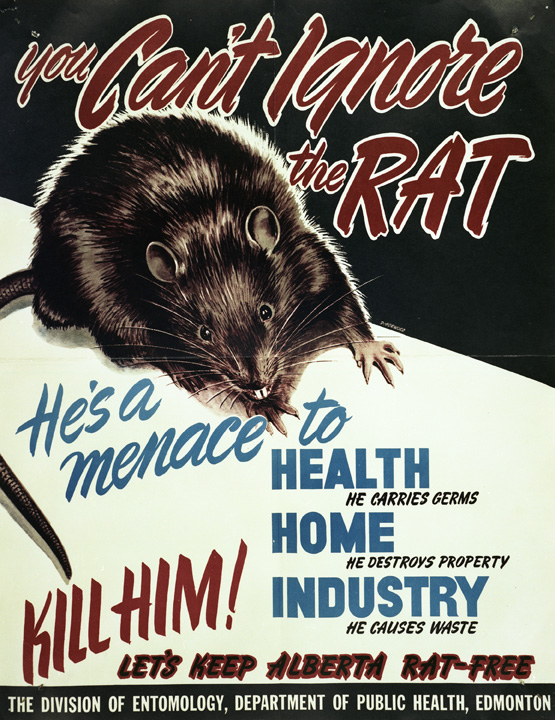

In 1948, the province’s Department of Public Health launched a propaganda campaign. Posters depicted the enemy, beady eyed and whiskered, alongside such slogans as “Rats are coming!” and “You can’t ignore the rat.” Within ten years, infestations dropped from nearly 700 to just over 100 and now sit at one or two per year.

In 2011, a pair of University of Alberta academics, Lianne McTavish and Jingjing Zheng, published a study of the semiotics behind the rat control poster campaign. They attributed its success to the World War II–style “us versus them” dynamic. “This format mirrors many of the military posters widely distributed in Canada and the United States during the war,” they note. “Implying that the rat-control program was another kind of war effort, the posters feature an enemy that could be defeated by dedicated Albertans intent on protecting their homes.”

Retired vertebrate pest specialist John Bourne recalls a classmate’s winning entry for a 1957 poster contest: “He drew a wonderful picture of a rat chewing on the province of Alberta, the eastern border, a kind of three-dimensional piece of the Alberta province shaped like a piece of pie. I thought that was so cool.”

Bourne ended up heading the rat control program from 1971 to 2006, and dedicated much of his time to raising awareness. With donated materials from the Provincial Archives of Alberta, he built a “beautiful replication” of a rat infestation, complete with nest, adult rat taxidermy, plastic rat kittens (yes, kittens), and damaged outbuildings. He toured the province with the model, visiting schools and farming communities, and built an interactive game to test kids’ knowledge of the rodent. He even resurrected the poster contest of his youth. In 1985, the winning image was “a super picture of a sort of cyborg rat with big claws and brilliant red, glistening eyeballs and saliva coming out of its mouth,” he says. The caption read, “We’re heading your way.” Such tactics worked—maybe too well.

“I had a lady who phoned me, absolutely terrified,” Bourne says. “She went into her bathroom to flush the toilet, and there was an animal in there that she just knew was a rat.” He followed up with a visit and found a soaked cat splashing around in the toilet bowl.

After he retired, anti-rat imagery and messaging waned. As the saying goes: success breeds complacency and complacency breeds failure. Rats, meanwhile, breed constantly. Last spring, six months before residents near Medicine Hat started spotting the creatures, Merrill was tasked with reigniting awareness at schools, at the border, and through the Internet.

The mark of his success, perhaps, will be more false sightings. “As long as we get people crying wolf, we know the general public is helping us,” he says. “Without the public reporting rats, we would probably be infested.”

This appeared in the March 2013 issue.