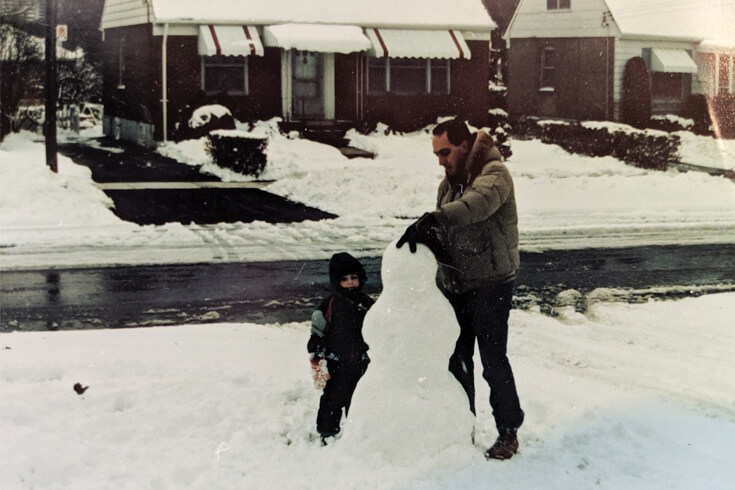

For close to a decade, I wore my dad’s old clothes. In my twenties, I was living in Montreal after college, in love with a girl, and I wanted to write poems and didn’t know what would happen to me. Back home, after thirty-five years together, my parents were breaking up in slow motion, the first ominous sign of which was that my dad was liquidating his closet. A melancholy windfall came my way. Sometimes it was he who offered them to me, with the cheery derring-do of a man going off to war—here’s that old silver suit you used to love when you were a boy, that houndstooth blazer I wore to your graduation. Other times it was my mom who gave the clothes over, offloading them in a grief she could palliate by giving me a sad, sweet gift.

Even if he was moving on, we couldn’t well throw his old clothes out. They were the costumes in a play that was coming to an end, but it had been ours. A man in this family could still wear them. We were almost the same age when we dressed in them. These had been the clothes of his thirties, and I wore them in my twenties. He’d been a little better off and a little bit smaller then than I was now. The beautiful thirty-year-old blazers fit almost perfectly, but were snug around the chest. Unwilling to tailor them, I wore them as they were, taut around the heart.

I only wanted to wear what I’d seen him in when I was young, and turned down anything too new. To a party in the Plateau, I wore the dinner jacket I remembered him in at our front door, in the house I’d never see again but still dream about, as he and mum headed out for the night. I wore one of his work suits to a Wu-Tang show, baffling my buddies. I relaxed in what he used to relax in. There was the old Gap denim button-down, whitening at the elbows, and the old green Gap T-shirt, shearing fashionably along the seams, which I was afraid to wash for fear of tearing it. I watched Jeopardy! in the shabby peach sweatshirt he used to watch Jeopardy! in, wondering if I could beat him now.

The best were the shoes. For a while there, before he fucked up his feet running, he had a taste for exquisite Italian loafers—sleek, low-profile, heeled, soft-leathered, with tassels. I wore each pair until I destroyed them walking. There’s something magical about wearing out your father’s shoes. He’d been young once, and cool, in love like me in some sundowned yesterday. His shoes were the emissaries of his past, and they almost fit me. Like my dad, my left foot is slightly bigger than my right, but both are bigger than his ever were, so I had to squeeze into his shoes. Even though they were slowly hobbling me, I wore them everywhere. People would fixate on them, thinking them too fancy for everyday life. I’d shrug. I couldn’t bring myself to preserve them for special occasions, where I now might not see him anyway. They were my special occasion. He’d held on to them for decades after he’d worn them, but I tore through them, one pair in a year, another in a single summer. Directionless, I wore them until the heels curved and the soles gave out, worn through with wandering, even long after the soft Italian leather had huge holes scoured into it, dirt and grit and glass sticking to my feet.

His clothes meant something—they were my armour against entropy, and however old they were, I’d wear them again each day if they would stave off tomorrow for another night. But, from my wearing them, they fell apart. There was the big red winter coat I loved, which I puked on one night, drunk. From the back of a cab, I remembered him wearing it as he drove me around when I was a kid. The dry cleaner did his best to repair the felt, but it never looked the same, so I stopped wearing it. The houndstooth jacket frayed after a few years, first in the elbows and then everywhere, and the suits stopped fitting or fell apart. The old Gap T-shirt all but dissolved in the wash, and even my excellent Portuguese cobbler couldn’t fix the loafers. I stopped watching Jeopardy! when Alex Trebek announced that he had stage-four pancreatic cancer, and I stopped wondering if I could beat my dad at the game. The old world was coming to an end, having been all used up.

And then, one day, there were no more clothes. He’d made a new life, and his closet, having been emptied out, was filling up again. It had been cleansed of everything that I remembered, which had been given to me to wear out. The whole enterprise of wearing my dad’s clothes had been a way to remember, then a way to forget. And, now, it was done. Wandering the aisles of Uniqlo and H&M, I wondered: Who should I look like now? The dopey model in the outfit without a history? All the bros in Blundstone and Carhartt? Or the lawyers I see striding to court in suits so bespoke that they could never be bequeathed, their little shocks of personality confined to zany pairs of socks? Like everyone else, I was in the disposable age of fast fashion, where clothes are as permanent as Instagram stories. The vogue couture was now amnesiac.

I missed showing up to a friend’s house in a steel-coloured sports coat from the eighties, a pleated pair of slacks on its last legs. They lived on only in our old photos, where, looking back, they looked huge on him, or made him look smaller than I remembered. And borne by them now was what I recalled from when I’d worn them too—the Armani jacket he’d worn to my first communion, which I wore in the author photo for my first book; the camel-hair coat he’d sported on dates with mom, which I unbuttoned, biking around Montreal, when I felt more in love than any man has any right to feel. The old armour went the only way that any work of human hands must go—to ruin. A man is who he wears.