On a flight from Toronto to San Francisco last August, I kept looking up from my book—Valeria Luiselli’s Sidewalks—to monitor the animation showing our progress on the seatback in front of me. Moments later, in an uncanny conflation of worlds real and imagined, I found myself reading about that same experience. “No invention has been more contrary to the spirit of cartography,” Luiselli writes, “than these airplane maps. A map is a spatial abstraction; the imposition of a temporal dimension—whether in the form of a chronometer or a miniature plane that advances in a straight line across space—is in contradiction to its very purpose.”

This resonated while planning our holiday: a two-week road trip that would begin in San Francisco, trace the coastal highway down to Big Sur, and then zip back up through Napa Valley and the redwoods before heading north into Oregon. Back in Toronto, booking campsites and bed and breakfasts online, Vanessa had mentioned that, years ago, her family had blazed a similar trail using something called a TripTik. I’d never heard of such a thing, as my own family vacations had tended to involve rented cottages (fun) and culturally edifying visits to India (less so).

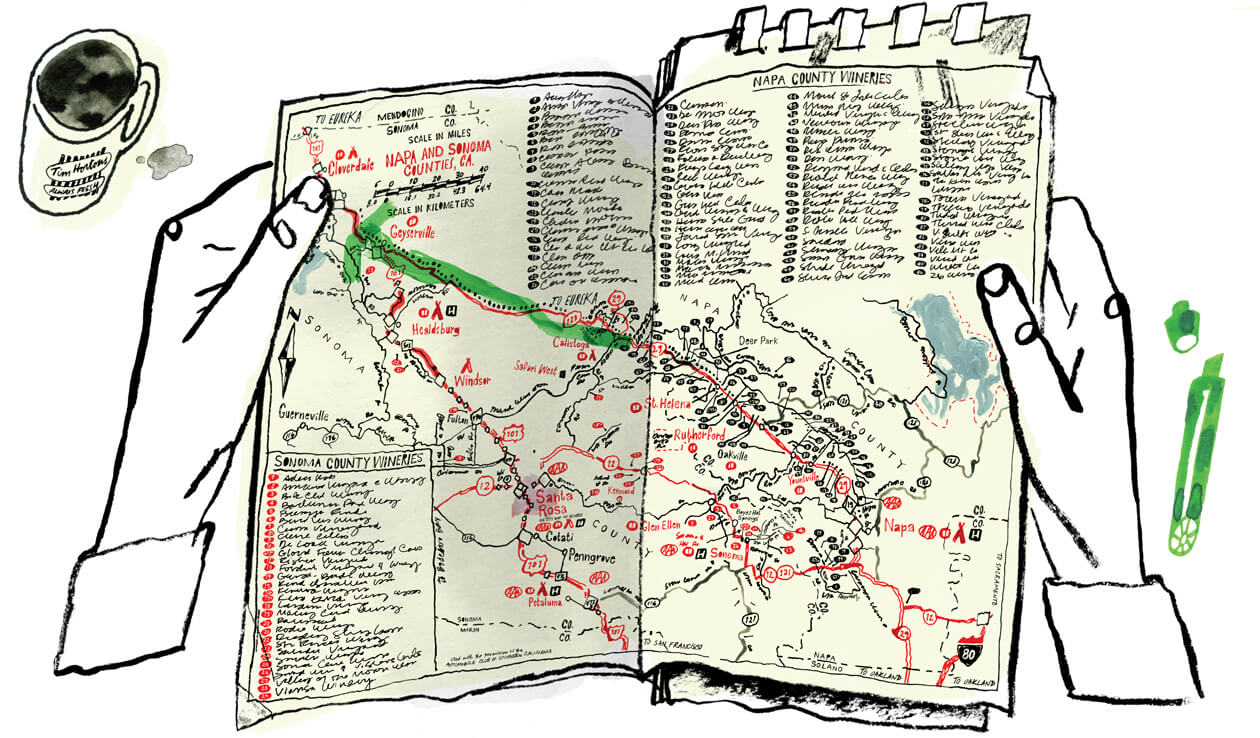

TripTik, she explained, was a service provided to members of the Canadian Automobile Association. Back when Vanessa was a kid, her dad would head to their local CAA outlet with a holiday plan, and an agent would plot a route for him in highlighter on a series of coil-bound maps. The TripTik was supplemented with relevant TourBooks, which detailed regional attractions, accommodations, and restaurants along the way. I was intrigued: like many quintessentially Canadian experiences that often elude the kids of South Asian immigrants (hockey, sloppy joes, sunburns), this seemed like something I might reclaim now, as an adult.

One of the great ironies of the coast around Silicon Valley is that the region hosts a number of wireless dead zones. So, faced with the prospect of being technologically marooned, we decided not just to TripTik our route, but to forgo satellite navigation entirely—no GPS, no Google Maps, no smartphones. Maybe freeing ourselves from virtual mediation would foster a more engaged travel experience; maybe it would be inconvenient and irritating. But for the sake of nostalgia, both real (hers) and invented (mine), we thought we’d give it a shot.

In the early twentieth century, as the automobile began populating the public imagination and roadways of North America, regional motor clubs formed to lobby for drivers’ interests. In 1902, nine independent chapters in the United States banded together to form the American Automobile Association, and eleven years later, an equivalent federation formed north of the border, officially becoming the Canadian Automobile Association on March 8, 1916.

A hundred years later, CAA counts roughly 6.2 million drivers as members. After almost seventy years of guiding intrepid Canadians around the continent, the association stopped handing out their hand-drawn offerings last year. Instead, they now direct road-trippers to their online TripTik Travel Planner, accessed by about a million people a year. So our trip to California, we like to think, was guided by one of the last handmade TripTiks ever.

Although CAA was phasing out the service, the Brantford, Ontario, office agreed to put together a paper package for us: “Picture a snow-clad mountainside,” instructed the authors of the Northern California TourBook. “A man and a woman in ski gear swoosh down an alpine slope. Cut to a sun-washed beach hours later. The same twosome strolls along the shore, water lapping at their feet. Then, at a swank urban bistro that evening they sit across from each other savouring a sumptuous dinner.” (Yes! Swoosh! This would soon be us!)

The TripTik seemed dubious: its coils were flimsy plastic, its paper only a grade or two thicker than newsprint, and our route, drawn by hand in green marker, wobbled from one section to the next. I was reminded uncomfortably of what travel used to be: a voyage into the unknown. There’s been a huge ontological leap from poorly folded roadmaps stuffed into gloveboxes to the immersive environments of Google Earth and dashboard navigation that responds to traffic and weather in real time. Now that cartography includes a fourth dimension, mapping is no longer a guide so much as a project of perfection: the best route, available immediately, updated live as you drive it. That we were heading to another country without that sort of guidance felt as foolhardy as it did liberating. What if we drove off the page?

Our first human interaction in America was at the San Francisco airport’s rental-car desk. For forty-five minutes, the man behind the counter performed a bewildering dance of legalese and hidden charges, including a $150 pass to traverse California’s toll roads. But, helpfully, our TripTik informed us that we would need to pay a total of only $6 (US) to cross the Golden Gate Bridge before flying back to Canada. Salesman thwarted, we got our car and hit the road.

The CAA TourBook’s alliterative claim that the SR-1 highway “snakes along . . . in a seemingly endless series of sinuous S-curves” didn’t prepare us for the jaw-dropping beauty around almost every twist and turn. And though it was circled on our TripTik as a single location, Big Sur actually encompasses a broad swath of stunning coastline, bordered by Carmel in the north and San Simeon in the south, from which the Santa Lucia Mountains heave inland. We stayed that first night at a semi-rustic, cripplingly expensive resort nestled in the woods off the highway; like many American restaurants, the affiliated “roadhouse” seemed to assert its patriotism via portion size.

TripTik aside, on our daily excursions up and down the coast, we were often so flabbergasted by the views that we overshot exits and missed turns. And there were limits to its purview as well: a few days in, heading back inland, we trawled every inch of the numbingly nondescript town of Gilroy in a panicked attempt to buy Vanessa a rain jacket (never worn). And in Ashland, Oregon, we wandered the downtown for forty minutes before locating the Shakespeare Festival, where we had tickets to see Pericles—a play, it so happens, that’s about being cast adrift and succumbing to chance.

Once, we even got lost in time. Having successfully TripTik’d our way to Shelter Cove, which marks the southerly start of the portentously named Lost Coast Trail, we thought we’d do a portion of it as a day hike. Since the route skirts the ocean for twenty-five miles, much of it is passable only at low tide and requires strict adherence to tide charts unless you wish to be swept out to sea.

Comparing the map and a newly acquired chart, we figured we had a couple of hours to get out to a point about four miles down the trail before the surf came in and we’d have to turn back. A spot on the horizon seemed to correspond to this marker, so we set out for it with one eye on the ocean and the other on our watches. The walk, over loose stone and wet sand, was gruelling, especially with our matching his-and-hers bum knees (MCL and ACL tears, respectively). On and on we trudged, and that little promontory grew no closer. An hour passed, then another. We stopped for water; we hurried past a bear and her cubs lumbering around in the trees up the bank. And still our goal seemed unreachable.

Then Vanessa looked back. “Um,” she said, “do you think maybe we’ve already passed it?” She seemed to be right: about a mile or two back, the waves were hungrily “lapping,” as per our TourBook, at a jut of rocks that resembled the one on our map with remarkable precision and over which we’d scampered an hour or so prior. After wading back to the trailhead and retreating in drenched shame to our hotel room, we realized that if we’d gone any farther, our only option would have been to bivouac up into the woods, where that bear and her cubs lay in wait.

It can be kind of nice to get lost—for a little while. “Leave the door open for the unknown, the door into the dark,” writes Rebecca Solnit in A Field Guide to Getting Lost. “Getting lost is not a matter of geography so much as identity, a passionate desire, even an urgent need, to become no one and anyone, to shake off the shackles that remind you who you are, who others think you are.” In these wired-in times, that seems easier said than done. You’re often only a couple of clicks away from rescue, be it in the form of social media’s salve for loneliness or an escape route plotted on your phone.

The thing is that I don’t actually need to lose my way to feel lost. I’m lost anywhere that I don’t know what to expect around the next corner. When I kept comparing another hike in the Redwood National Park to the Green Gardens walk in Gros Morne National Park, Vanessa remarked on this constant need for analogues. It seems a human enough tendency to comprehend through association, but I had to confess: the unfamiliar makes me anxious until I’ve slotted it into some pre-existing category of understanding.

So when I travel, I require an anchor. And though the TripTik was just a few sheets of paper, it started to serve as a sort of cultural touchstone. CAA has always struck me as one of those intrinsically nationalistic organizations, akin to Canada Post, the CBC, and the CFL. The TripTik became my link to home. I began to enact a sort of archetype of Canadianness: at a coffee shop in Eureka, for example, I asked, “Where’s the milk ’n’ that, eh?” which caused Vanessa to wonder when I had started speaking like an OHL assistant coach.

Our triptik wasn’t just a guide to our vacation; it provided a vacation in itself. Travelling a route sketched for us by human hands, liberated from technology’s mediating influence, I experienced less a personal emancipation than a reversion to my more basic instincts. A paper map has edges; a virtual map sprawls limitlessly over the surface of the globe. The spatial limitations of the TripTik created a sense of finitude and constraint; you have to trust yourself a little more, especially when you find yourself beyond its pages.

We’d booked our final night in California at a Bavarian-style inn on the Russian River, planning to go out for a nice meal and relax before a leisurely drive back to San Francisco the next day. After we checked in, Vanessa fired up her phone to prepay our toll across the Golden Gate Bridge and asked me the date. “September 8,” I said with confidence. “And we fly out September 9 at five in the morning.” With dawning horror, she looked from me to her phone and back. “But that’s tonight!”

There’s a special kind of ineptitude that treads the line between adventure and annoyance. I will not claim to have been happy about racing down Highway 101 at 2 a.m. to catch our flight home. Nor would I suggest that a mobile device, programmed with some sort of alert or alarm, would have entirely prevented such a thing. Those were a silent, tense few hours in the car, each of us blaming ourselves and the other equally. But by the time we got to the airport, our moods had lightened. “Well, we made it,” said Vanessa, and kissed me on the cheek. I smiled, kissed her back. We had, indeed. This, too, had already become just another story.

This appeared in the July/August 2016 issue.