On Saturday nights, as 7 p.m. nears, I pour popcorn into a bowl and a cold beverage into a glass, and I seat myself in my preferred spot on the couch, closest to the television. I change the channel to watch the Toronto Maple Leafs play hockey. Streak or slump, I tune in as I’ve done since I was a child growing up on the reserve. This expression of fandom is more than just a ritual and more complex than just supporting a professional hockey team that is both beloved and reviled. Like those of so many other sports fans, the roots of my devotion are intergenerational.

I grew up in Wasauksing First Nation, an island community on Georgian Bay near Parry Sound, Ontario. I’m of mixed Anishinaabe and Canadian heritage: my dad is from the rez, and my mom is from town. I don’t remember when and how, exactly, I became a Leafs fan as a kid in the 1980s; the team has always been a part of my life and a part of my father’s. We didn’t have hydro in our home until I was about eight years old, so I was introduced to my favourite sports team off the grid. My earliest memories include my dad connecting a small black-and-white TV to a car battery in order to tune in to CBC on the rabbit ears and watch Hockey Night in Canada. We eventually got electricity and a colour TV, and antenna reception improved enough to watch games more regularly. The late ’80s were hardly a glorious era for the Buds, but the period was defined by Wendel Clark, a mustachioed forward whose physicality, grit, and scoring prowess still made the game fun to watch.

Everything changed in the early ’90s. The Leafs became a Stanley Cup contender thanks largely to the addition of Doug Gilmour, a small but speedy centre forward. The team made the conference finals two years in a row—the first time to lose due, arguably, to a non-call on a high stick committed by the most famous hockey player in the world, Wayne Gretzky, on our beloved Gilmour. It’s a moment that will forever live in infamy, but it solidified my love for an immensely skilled team that just couldn’t quite make it to the pinnacle. As the years went on, so did the championship drought, one that dated back to a year burned into our collective psyche: 1967. That was the last time the Leafs hoisted the Stanley Cup, over their rival Montreal Canadiens.

My devotion only grew stronger as I grew older, especially once I moved to Toronto, in the fall of 1998, to study journalism at Ryerson University. As a student, I couldn’t afford tickets to games, but living just a few blocks from Maple Leaf Gardens was thrilling. Mats Sundin, our captain from Sweden, quickly became my favourite player, and the tough, blunt head coach, Pat Quinn, produced results. Toronto became a perennial playoff team, reaching the conference finals twice in a four-year span. After suffering through futility during my childhood years as a fan, enjoying expected annual success as an adult felt like redemption. A Stanley Cup championship continued to elude the Leafs, though, and they regressed into a dark era of disarray and failure as the 2000s went on. I’ve seen and heard all the jokes about the team at this point in my life. They always make me laugh, especially the image of a horse-drawn wagon captioned something like “Photo of the last Leafs Stanley Cup parade.”

A glimmer of hope has returned in recent years thanks to the arrival of forwards Auston Matthews and Mitch Marner. I was in the stands at their first game—in Ottawa, against the Senators, in October 2016—when Matthews scored four goals. No other player in the modern era has scored four in their debut. It was impossible not to see a brighter future. The Leafs have since developed, once again, into a team that makes annual playoff appearances, even though a Stanley Cup still feels so far out of reach. I patiently await ultimate success, as I have for my entire life. That hope is rooted in something. It’s a result of a proud, strong, global network of fans: Leafs Nation. I always have my phone handy on game nights to check in on Leafs Twitter, join group chats with friends, and occasionally text with my dad, John.

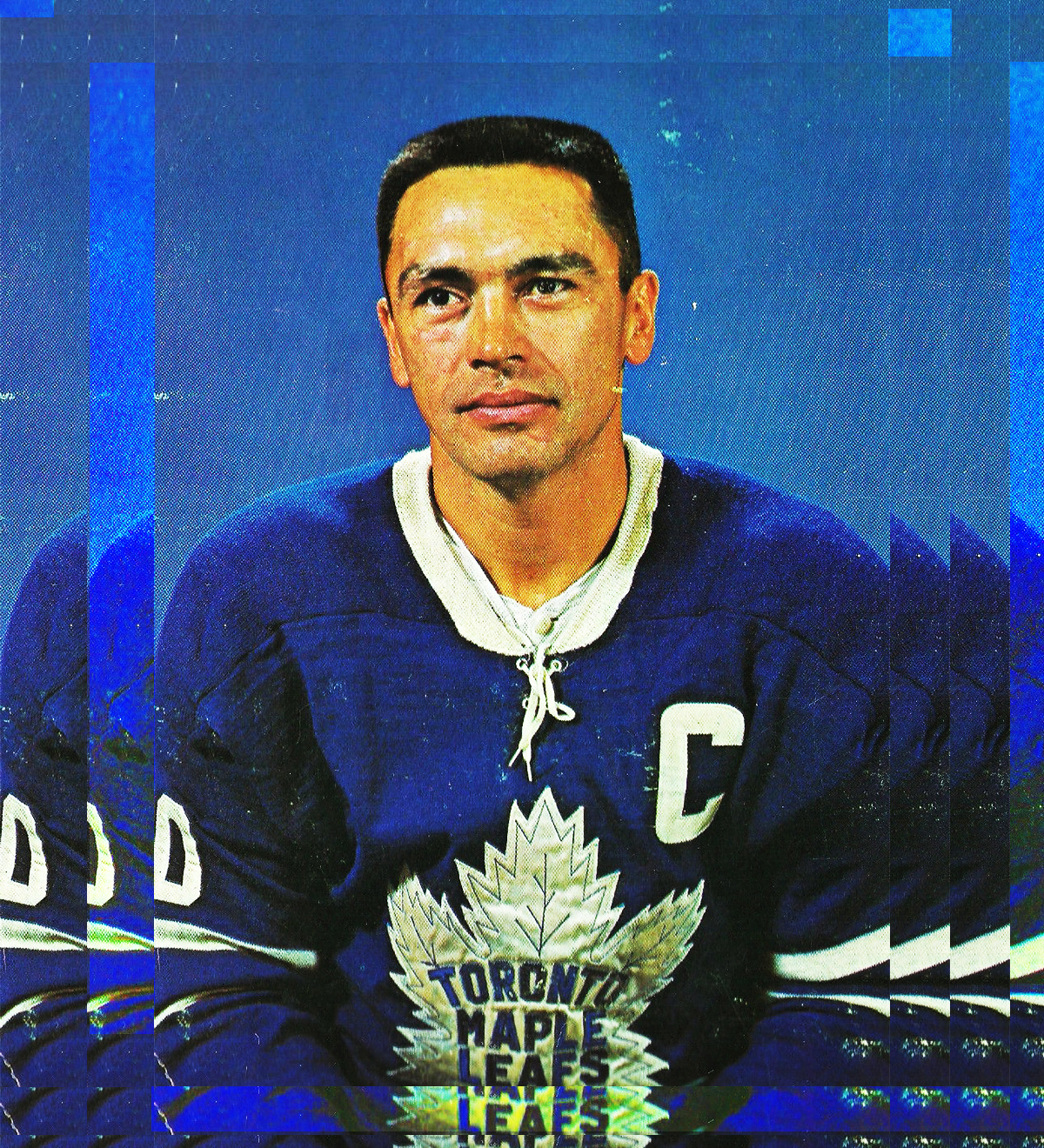

In the middle of this pandemic-shortened season, I texted my dad during a game against the Edmonton Oilers to ask about the origin of his allegiance. “The blueberry stains on my butt at birth is proof I am genetically a Leafs fan,” he jokingly texted back. He told me he’d been a fan for as long as he could remember. He started watching games with his cousin at their grandmother’s house, but he remembers it being a visit to Wasauksing by one particular Leafs superstar, sometime back in the 1960s, that affirmed his fandom for life. “My first experience with hero worship was the winter George Armstrong came to visit our little community hall,” he wrote. “It was awesome seeing a Nish that played professionally on TV. To see him in real life was legendary.” Armstrong, the captain with Algonquin and Irish roots who had led the team to Stanley Cup glory in ’67, was an iconic Indigenous player. He provided representation on a mainstream stage in a country that oppressed and neglected people like him and those he inspired.

I posted on Facebook asking Indigenous fans how they came to be passionate about the team from Toronto, the big city far from many of their small communities. Most respondents who appeared my age and younger said it was because their parents were fans, which explains the unwavering devotion despite recent failures. They recalled watching games at home, on the rez, with their parents, or listening on the radio while at hunt camp. It seemed like every older fan mentioned one name: George Armstrong.

Armstrong died, at the age of ninety, earlier this year. I’ve seen how massive his legacy is, especially in First Nations throughout Ontario. I wanted to ask someone close to him about that, so I messaged Ghislaine Goudreau, an Anishinaabe educator in Sudbury whose grandmother was Armstrong’s cousin. “I personally think he inspired anyone who saw him play and who knew him,” she responded. “In many ways he was a born leader. He had lots of respect for his Indigenous mother. The leaders traditionally in our communities were the women.” Goudreau described the racist taunts Armstrong endured as a child and the horrors his relatives survived at residential school, which he fortunately was able to avoid. She believes his experiences fostered a strong sense of empathy and compassion, which she saw him extend to anyone who came into his circle.

“As Nish we always fight for the underdog because sadly, we’ve been put into that position,” Goudreau added. “That is why so many of us are not giving up on the Leafs even though George is the last captain to win in 1967.”

It is this hope, which thrives in our communities despite the Leafs’ decades-long championship drought, that connects us to the team and its fan base. It is choosing to be part of something unifying even though Indigenous nations and cultures in this country have long been violently pushed to the periphery. While this hope is pinned on something entirely out of our control, it is by no means trivial. Hope for a healthy future is what pulled many Indigenous people through the heaviest traumas of colonialism, which still reverberate today. When settler authorities outlawed ceremonies, stole children, and brutalized them for speaking their language, communities held on to hope that, one day, the old ways would be able to return and would be celebrated. That process is underway across the land.

In this sense, being a diehard Indigenous fan of the Leafs—or of any hockey team, for that matter—is a paradox. Hockey is widely considered Canada’s game, a sacred pastime that purportedly brings people together to celebrate the virtues of this country. But anyone who inhabits the margins knows that’s a fallacy. Canada’s history is horrendous, particularly its treatment of Indigenous people. So, as an Indigenous person, to latch on to something so intrinsically Canadian can feel contradictory.

The sport itself has long embodied and perpetuated bigotry and inequality. In recent years, a reckoning has come, with players of all backgrounds speaking out about the racism and discrimination they’ve endured from other players, coaches, management, and leadership at all levels. Racist, homophobic, misogynistic, and other discriminatory language has long been part of the game’s parlance, both on and off the ice. The first time I was ever called the R-word was while playing in a novice house-league game at Parry Sound’s Bobby Orr Community Centre.

Considering all this, I have a conflicted relationship with my favourite sport. I admit to engaging in a level of cognitive dissonance when celebrating the moments that make me happy. And, as a Leafs fan, I know first-hand that those big events, bursting with joy, are few and far between. Still, it’s a choice I make, and I recognize all the contradictions that arise when I wear those colours, that maple leaf, and inhabit that realm.

Perhaps it’s the choice itself, to become part of a wider community that’s steeped in tradition and carried by hope, that appeals to Indigenous Leafs fans like me. The devotion unites us with fans from other cultures and communities, and we’re bound by the stories, the dreams, the heartbreaks, and the triumphs. We’re all holding out hope for the ultimate payoff of that lifelong dedication. “We know one day [the Leafs] will be victorious,” Goudreau wrote at the end of her message to me. “We’ve had small victories along the way, and we are never giving up.”