Seven years old, Wilson Avenue

I had been sent to live with my dad. The tiles on the kitchen floor were red. There was a blue melamine table whose surface was covered with small gold stars.

My dad told me he’d learned how to cook in a prison kitchen. He had a wonderful recipe for butter cookies. He got me to help him make the round bits of dough and drop them on the baking sheet. He cursed at me the whole time, saying I was doing it wrong. Then he pressed each one down with a fork. That required artistry.

The next morning, I put the cookies in a Tupperware container and hurried off to school. I placed them on the table with all the other sweets at the bake sale. And even if you looked hard, you would not be able to determine which belonged to a child without a mother.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more Walrus audio, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Fourteen years old, Wilson Avenue

I was standing barefoot, talking on the phone with a girl from school. The red telephone was screwed onto a wall in the kitchen and was covered in stickers with important numbers: the hospital, the high school, the fire department, the taxi service, the pizza parlour. That was when telephone cords were really long, and I wrapped it all the way around my body as I was talking. It was as though it were a climbing vine that had sprung up from the ground and was circling me. It was as if I were Sleeping Beauty, and I might fall into a trance and go to sleep and not witness my whole life pass by. Any girl can miss her whole youth, waiting to be kissed. Like Sleeping Beauty, she is in danger of going through life with her eyes closed.

Seventeen years old, Clark Street

The apartment was a dive. There was no way to defrost the freezer. It was just a solid block of ice. When you opened the door, it was like looking out a small window after an avalanche.

I couldn’t find a roommate because there were so many cockroaches in that kitchen. I would find them inside my teacups in the morning. Cockroaches were underneath the wallpaper. They would crawl into the drain and then come out of the faucet. I drew a line with special chalk on the floor in the kitchen doorway to keep them contained.

Still, I was happy living on my own. Next to the door, there was a bronze light-switch cover that had a pattern of climbing roses on it. One day, at a garage sale, I bought a matching painting of a rose to hang above my table. I decided then that there would be more and more roses in my life.

Eighteen years old, St. Dominique Street

I lived in a rooming house and didn’t have a kitchen. Instead, I had a small kettle with red peonies on it and a hot plate that I kept on the counter by the door. I thought that hot plate was so practical. You could carry it in a box when you moved. You could put it in a suitcase and bring it on the subway. My cooking problems were solved for life. My hot plate made me feel like a poet from the 1930s. There was something about it that negated domesticity. It made me the type of woman Henry Miller would fall in love with.

My boyfriend would come over almost every night, and he would explain to me why I wasn’t the type of woman he would marry. He said he never saw himself spending his life with a girl who had a hot plate. He wanted me to want things like couches. He wanted me to recreate his childhood home.

I also thought he wasn’t the type of guy that I would marry, but I kept letting him come over. I thought we had some okay times, but he disagreed. We broke up.

Nineteen years old, de Bullion Street

There were pretty teacups with green and yellow roses, long-necked swans, and smiling, dainty ladies in the cupboard when I moved in. When I washed them, they floated in the sink like water lilies. Someone had placed an old anthology of feminist writings from the likes of Germaine Greer, Angela Davis, and Andrea Dworkin under the sink to absorb the drip from a leaking pipe. It got larger and larger with each drop as though it were about to explode.

There was a postcard of a half-naked girl in stockings painted by Egon Schiele on the fridge. She looked like she wanted to be loved so badly. She wanted you to pull her stockings off by the big toe. She wanted to be told she was the one. But there was something about her face that signified that she would always be rejected. You could tell that she gave her love too easily.

Twenty years old, St. Denis Street

I moved in with my new boyfriend. There was a large crack in the ceiling above the cupboards. The faucet made too much noise, like a giraffe with a hairball. I didn’t call the landlord, though. I hated repairs. They made things ugly and characterless.

My boyfriend had a white cat that was always on top of things. He would be on top of the fridge. He would be on top of the table. He didn’t really have any interest in the floor. Instead, he hopped on from surface to surface, touching everything with his paws as though he were offering benediction.

After I got pregnant, I thought we would be okay together.

Twenty-one years old, Park Avenue

We moved to a smaller apartment closer to downtown. My daughter sat on her high chair in the middle of the kitchen for most meals. There was always a group of plastic figurines on the tray. They would have to perform a small theatrical revue before she took a bite.

The figurines were a motley troupe of travelling actors performing in a city square. The leader was a zebra whose stripes had begun to wear off and who was now almost entirely white. A small black chimpanzee, whose face was painted pink, sat cross-legged, happily holding a banana in his hand. There was a boy with blond hair who, for reasons I could not say, had a pot on his head. A pink turtle, whose shell was painted green and brown and had marks of a dog’s bite on it, added gravitas to the company. And a Smurf in striped clothes who had just gotten out of jail gave it edge.

They sometimes pretended they were in a battle against one another. They had a skit where they were hopping along merrily and then fell off the edge of the high chair. There was a play where they rode around on a spoon as though it were a jet of sorts. They sang “Dig a Pony” by the Beatles. They sang about being lonely.

I had kept these figurines with me since I was a child. Once upon a time, they had also performed for me. But back then, the nature of their repertoire was quite different. Their plays were darker, more medieval. The zebra, who had been so much younger, had had a devilish smile and liked to talk about the sinister. He had encouraged me to believe there were monsters underneath my bed. Now that he was older, he no longer saw the point in wickedness. He would take whatever work he could get. He had no problem performing something that could be construed as naive.

Twenty-two years old, Bernard Street West

There was a lace curtain covering the kitchen window, which looked out on the street. Although I could see people passing by, they could not see me. I stood in front of it in a paisley pajama top and underwear, my hair like a bird’s nest on top of my head, and wondered whether this was what ghosts felt like.

A door in the kitchen led to the fire escape. There was a clothesline out there, and I hung all my underwear out on it for the world to see: my delicates shivered in the breeze, self-conscious.

I had left my daughter’s father. He had been stealing all my money. He would come home when he had blown it on getting high. I had nothing for the baby or myself. Whenever I slept with a man, he seemed to think that everything I owned belonged to him.

There was a geranium on the window ledge. The petals fell off one by one as if to say he loves you, he loves you not. Then there were no more petals, so it didn’t matter that much anyways.

I shut the kitchen window because there was a cat in heat outside and she was crying. She sounded like she was pleading for her life. It was hard to believe that she was just horny. You could always hear women begging not to be left in the summertime. It had nothing whatsoever to do with love; they were just terrified of being alone.

Twenty-five years old, Wilson Avenue

My dad got me a cheap apartment in the complex where he worked as a janitor. I was fifteen feet away from my childhood home, only now with a daughter. When I left the apartment, I could see the “PAT BENATAR” I’d scribbled on a wall fourteen years before. Nearby, my tiny handprints were still idling in the sidewalk from the time I wanted to be a movie star. Seeing them made me feel like I’d disappointed that little person who had dreamt of going far in the world.

Our front door was right next to the kitchen. The doorbell was too loud; it sounded like a fire alarm. I would startle and drop my cup whenever it rang, which it often did. When you are a young single mother, neighbours come over uninvited bearing second-hand things, such as winter clothes and light fixtures and rotary phones. They also brought boxes and boxes of dishes, sets that were missing pieces, ones that a despised grandmother had left behind. Within a few weeks, I had an impressive collection, a mad children’s anthology: dinnerware scenes of sheep gallivanting, small yellow peonies, an abundance of snowflakes, cats lying in round circles, screeching roosters, malevolent bunnies chasing each other with garden tools.

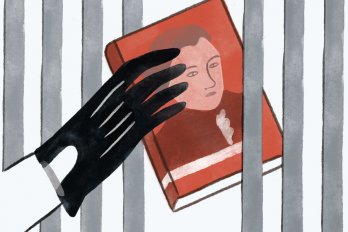

I had ambitions of writing stories of my own. As the plates and glasses piled up in the sink, stacks of paper grew on all the kitchen chairs. But I still had to work dumb jobs to pay the bills, and there was the chaos of raising a child on my own. I thought I would never be able to finish a novel. I couldn’t even wash the dishes. There were hundreds of them.

Thirty-three years old, St. Urbain Street

There were postcards on the fridge door. In one, a woman stood on her balcony in Paris, her hair in a messy bun, looking out at the marvellous city below. There was one of Simone de Beauvoir writing in a notebook at Les Deux Magots café and another of Margaret Atwood typing out the manuscript for The Handmaid’s Tale in a large empty room. There was also a photo of Marguerite Duras taken when she was a teenage girl, her face a perfect circle, looking like a polished stone. It is a face so strangely petite and vulnerable and defiant that it became a mystery even to her.

I was working on my second novel at the table. Its surface was covered with notebooks and books and Post-it Notes. There were piles of papers and manuscripts on top of the counters. It was as though I were creating a great feast of words. This was the kitchen that I had always wanted to be in.

The kitchen is where women have always been relegated. It is not considered the place from which great ideas and magnum opuses emerge. But kitchens are where I scribbled notes late at night between chores. They are where I sat when women came over and we drank wine and made sense of our dreams and everything that held us back. My kitchens are where I sat for a moment each morning, holding a cup of coffee in my hand. The kitchens in my life were always trying to tell me something, but I didn’t always know how to hear them. This one said that it was all right to put myself first, and the dishes would indeed wash themselves.