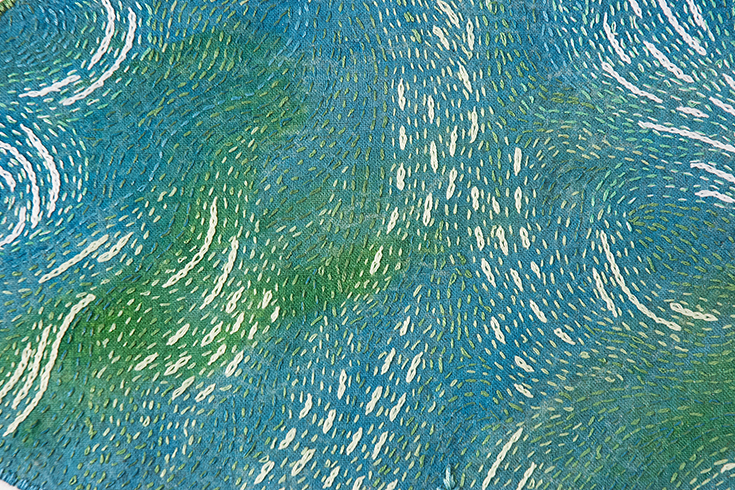

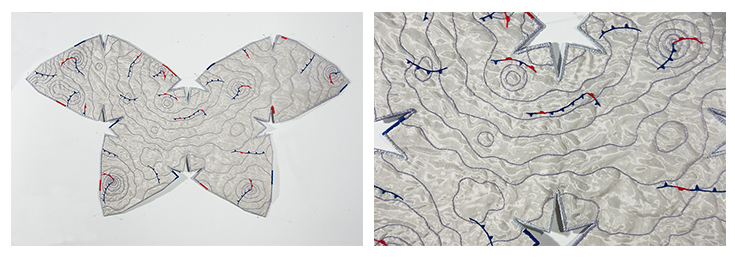

Dramatic swirls of white thread bind rain-soaked clouds, bolts of blue and green trap intense winds, and atmospheric pressure fluctuates moodily on pearly-grey linen. Running stitches patiently over her hand-painted fabrics, Vancouver-based artist Bettina Matzkuhn brings a sense of stillness to something ever changing. Matzkuhn’s series Weathering includes a collection of shifting weather patterns and climate phenomena embroidered onto twelve vibrant textile pieces all shaped like butterflies; the resulting kaleidoscope of fabric is called Schmetterlinge, the German word for butterflies.

For Matzkuhn, the elaborate work is a way to slow down and document the world as it changes around her. “The glacial pace of embroidery suits me,” she says. “It’s like thinking with your hands.” Each piece might take weeks to complete. With a needle and thread, Matzkuhn is trying to understand, worry about, and celebrate our natural systems.

Matzkuhn first learned to read the weather from her father, a refugee from East Germany, in the sixties. The textile artist practically grew up on a boat, going sailing with her family every weekend in British Columbia. She also learned how to connect what was on a map with what was in front of her. She understood, for example, that the narrowing contour lines on a topographic map signalled steep mountains ahead. Geography became the context for how she saw the world, and she’s been exploring the science with her art ever since.

At age ten, she embroidered a cross-section of Canada onto the strap of her guitar—a journey from the Atlantic Ocean, across the flat expanse of the Prairies, to the forest-carpeted mountains of BC. After studying art at Camosun College, in Victoria, in the seventies, she made several experimental films for the National Film Board, using animation to bring her tapestries and textiles to life and to record her ocean-going childhood. At forty, she sewed scenes from a 2,300-kilometre solo bike trip, from BC to the Yukon, onto a spool of cloth. Then, in her mid-fifties, she embroidered four sets of twelve-foot sails as a memorial to her seafaring father.

Just as her father had unravelled the mysteries of the winds in a boat’s sails, meteorologist Uwe Gramann helped Matzkuhn decipher the language of meteorology for Weathering. Matzkuhn gave Gramann a textile piece depicting a cumulonimbus cloud (or a thundercloud) as a thank you for a crash course on weather maps. One of the resources Gramann shared with her was the online data visualization that inspired Schmetterlinge to take flight: a series of differently shaped maps displaying data such as wind speed, temperature, precipitation, and carbon dioxide. One of them was the Waterman butterfly projection—an update to the Cahill butterfly projection that seeks to display the world without distorting the shapes of its continents. The map is shaped like a butterfly, but sewing its edges together turns it into a polyhedron, a three-dimensional representation of Earth.

As soon as Matzkuhn saw the projection, she thought of the Victorian craze for collecting impaled butterflies in cabinets. “The world is fragile,” she says, reflecting on Schmetterlinge.

On hiking trips, Matzkuhn has noticed glaciers receding, seen cedars turning brown from drought, watched the spread of the tree-killing mountain pine beetle, and breathed the smoke of worsening wildfires—all effects of climate change in BC. In a world increasingly defined by climate emergencies and a public health crisis, understanding our impact on the planet can feel complicated. Matzkuhn’s work encourages us to take the time to linger and to wonder about our fragile world—piece by piece, with careful hands.