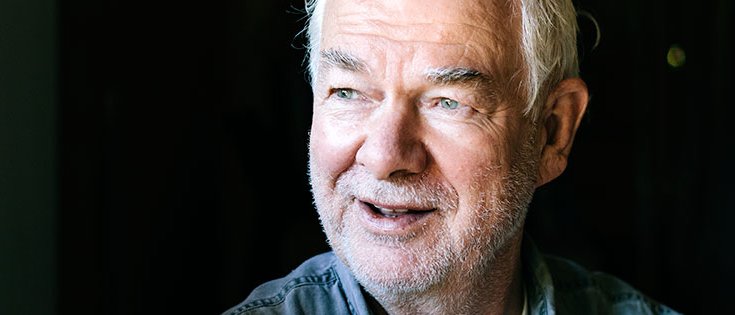

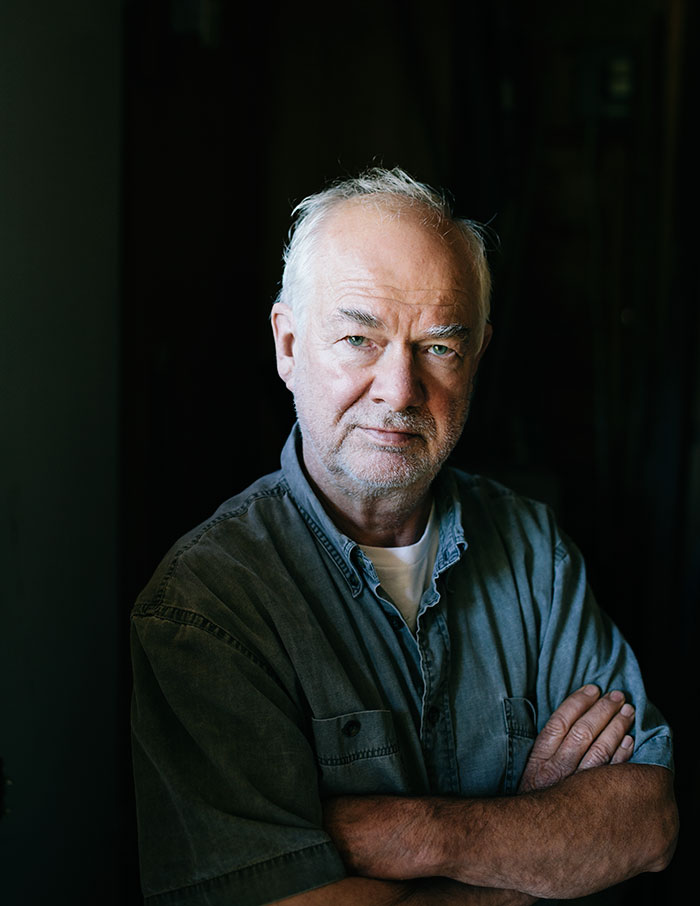

In mid-October of last year, as protesters were being arrested in Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park and 1,500 occupations had sprung up around the world, half a dozen Adbusters staffers gathered at the round table in Kalle Lasn’s sparsely furnished office, at the magazine’s headquarters on the west side of Vancouver. Few protesters in New York would have known the then sixty-nine-year-old publisher by name, or that the Occupy movement was set in motion by one of his signature mind bombs: a poster of a petite ballerina in a black leotard striking an arabesque and Photoshopped onto the back of the iconic Wall Street bull, a phalanx of police in riot gear emerging from the tear gas behind them. Simple, haunting, and prophetic, the black and white image is at once weird, funny, and even sexy. Like any of his most powerful “subvertisements,” it is designed to stop you in your tracks and make you reconsider the world around you. Over the ballerina, in red letters, hung the words “What is our one demand? ”Printed below was “September 17th” and “Bring Tent,” and the all-important Twitter hashtag #occupywallstreet.

Because we live in an age when Marshall McLuhan’s global village has emigrated to William Gibson’s cyberspace, it seems appropriate that the protest that rocked New York, and then the world, would be born on the opposite coast, in another country. Occupy is similar in tenor and tone to Lasn’s numerous other attempts to subvert mainstream consumer culture over the past two decades, employing print, television, and all of the latest web and social platforms to rouse the rabble. What was different in 2011, and part of what allowed the movement to spread so fast, was that technology had finally aligned with Lasn’s ambitions. Occupy Wall Street was the first of his mind bombs to go nuclear, and the #occupywallstreet hashtag is his most successful meme to date. (Coined by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in the ’70s, the word “meme” is now used to describe ideas, imagery, and concepts that go viral.)

While the Occupiers miraculously appeared in New York on September 17 (the date Lasn had chosen, to commemorate his mother’s birthday), and some even brought tents, most forgot to pack the most important thing: that one demand, the answer to his poster’s question. So Occupy captured the zeitgeist and harnessed the anger of an age, but it failed to make any real impact on the public dialogue beyond the slogan “We are the 99 percent.” Cool. But what did the 99 percent want when they chanted, “When do we want it—now!”?

Lasn knew what he wanted, and perhaps he should have added another line to the poster to spell it out, instead of sharing it in the weekly tactical briefings that went out to his 100,000 newsletter subscribers, friends, and fans. He hoped Occupiers would push for something like a Robin Hood tax. Based on a proposal first made by Nobel Prize–winning economist James Tobin in the early ’70s, this is how Adbusters interpreted it for one of its blog posts: “The tax would take approximately 0.05 percent from currency exchanges and speculative banking transactions, forcing those who caused the financial crisis to pay for it.”

By the time “Occupy” had been dubbed the word of the year and one of the ten biggest protest movements in American history, Lasn was already spitballing ideas for the next campaign, which would pick up where Occupy left off. He has always seen his magazine, and the non-profit foundation that publishes it, as a launching pad for revolution; and with editions in Canada, Britain, Australia, and the United States, Adbusters may be Canada’s best-known magazine beyond our borders. He was thinking small and wanted to spur more local protests, everywhere. Meme Wars, his forthcoming economics textbook, was already in the works; he wanted to break in to the University of British Columbia economics department and plaster the halls with posters challenging the classical economic theory that led to the 2008 financial meltdown and the Wall Street scams he calls “casino capitalism.”

He was especially excited by the idea of nailing manifestos to the doors, like Martin Luther but with a postmodern touch: for the stunt, he wanted to wear the iconic protest symbol, an Anonymous mask, just like the stylized Guy Fawkes masks all the cool kids were getting arrested for wearing at the barricades in Manhattan.

Lasn considers himself “a meme warrior,” albeit one who is more at home fighting from behind a mask. The most important battles today, he thinks, are being fought with and about ideas, and now that the Internet has levelled the playing field the best meme finally has a chance to win. He remains wary of the mainstream media, in particular television, worrying that the medium would trivialize his message. “As soon as you go on TV and people see your body, your flesh, your body language, and all the rest of it, you lose your gravitas,” he explained later. He and his Adbusters colleague Micah White gave print interviews for Occupy while other leaders, would-be leaders, and bandwagon jumpers hogged the TV time. And so, despite being Canada’s most influential media critic since McLuhan, Lasn made little effort to become the face of Occupy.

This is not to say he is unambitious. He regularly starts sentences with the phrase “Not to be grandiose, but…” only to finish with some kind of grandiose idea about how the Occupy movement, his new book, or the next campaign could be a global game changer. His 1999 manifesto, Culture Jam, was translated into seven languages and became a staple of communications courses across North America. It also became a handbook for aspiring shit disturbers, an Anarchist Cookbook for people looking to bake memes and messages. In it, he reveals the full extent of his revolutionary ambitions: “Our aim is to topple existing power structures.… We believe culture jamming will become to our era what civil rights was to the ’60s, what feminism was to the ’70s and what environmental activism was to the ’80s.” Culture jamming, he says, is an exercise in media martial arts wherein you use your opponents’ strength, profile, and pocketbook against them, to flip the message and start a new conversation. He has employed this strategy to “uncool” corporate campaigns and corporations, and to challenge economists to calculate the true price of progress, taking into account the cost of environmental degradation. One of his earliest economic memes, which no longer seems so radical in the age of climate change and carbon tax credits, was that “economists must learn to subtract.”

By 1988, a single clear-cut on the northwestern tip of British Columbia had left a scar large enough to make it one of the few man-made creations visible from outer space. As BC’s war in the woods heated up, an increasing number of activists were talking about the value of trees versus timber. Lasn, like many of his fellow environmentalists, was in a perpetual state of outrage, fuelled in part by an ad that promised “Forests Forever”—written by a group that represented the logging companies. Instead of kicking a hole in his TV or joining a logging road blockade, he set out to respond in the same medium with his own message. At the time, he was directing documentaries for the National Film Board, so he and half a dozen filmmaker friends crafted a thirty-second stop-motion animation spot in which a tiny tree with ET-size eyes asks in an irritatingly adorable kid’s voice, “Grampa, will I grow up to be big and strong like you?”

Chainsaws roar in the background as the gnarled old-growth answers, “I sure hope so, son.”

“Why wouldn’t I, Grampa?”

The cutesy cartoon images fade to a slow pan across a heartbreaking real-life clear-cut. “Unless something’s done soon, big old trees like me’ll be nothin’ but a memory, like the giants in the old fairy tales.”

“But Grampa,” asks the sapling, “what would the forests be without old ones like you?”

“I think they call it a tree farm, son.”

The anti-ad concluded with Lasn’s first great meme: “A tree farm is not a forest.”

Although he and his cohorts could not afford to run the ad in prime time, off-peak commercial slots could be bought on CBC for just a few hundred dollars. When he tried to purchase airtime, the network’s advertising sales people laughed him out of the room: it was against CBC policy to air advocacy ads.

These days, an anti-ad would go viral on YouTube within minutes, especially if it was deemed too hot for TV, but back then there was no alternative medium to turn to. Lasn was livid that the public did not have access to the public airwaves—not even on Canada’s publicly owned network. Corporate greenwashing of “Forests Forever,” he argued, qualified as advocacy, too. Unable to defend the doublethink required to explain how ads from people in favour of cutting forests did not qualify as advocacy, CBC chopped “Forests Forever” within a few weeks.

That exchange spurred Lasn and his friend and fellow NFB filmmaker Bill Schmalz to launch the Adbusters Media Foundation in 1988. The non-profit group promised to publish “a journal of the mental environment,” and to run anti-consumerist campaigns, both in their new magazine and on TV—if they could get on TV. Early issues of Adbusters focused on the usual West Coast eco-politics, but Lasn’s passions, which define the content of his magazine, soon evolved to focus less on trees than on the messages we print on them after they are turned into paper.

He went back to broadcasters in 1993 with a cartoony ad for BC’s iconic environmentalist organization, Greenpeace. The new subvertisement depicted a dinosaur made of cars as a voice-over heralded “the end of the automotive age.” The Adbusters Foundation bought two commercial spots for the CBC car review series Driver’s Seat. The first time the ad aired, he imagined jaws dropping and minds opening across the country. But when he called to book a second spot, he was told that the “Autosaurus” ad had been scrapped after more lucrative advertisers complained. In response, Lasn sued CBC for violating his constitutional right to free speech.

The network fought back, and the BC Supreme Court ruled in its favour. Lasn refused to back down and spent the next fifteen years appealing, fighting for access to a medium that was becoming less relevant during each new round of deliberations. In 2009, the BC Court of Appeal unanimously agreed to overturn the ruling, but by the time he had won the right to pursue legal action against CBC and Canwest for refusing him access to their airwaves, television was no longer the ideal delivery system for subversive messaging. The place to start a revolution was now online.

Lasn was born in Estonia in 1942, and his early years set the stage for a life as an outraged outsider. When he was two, his family crossed the border into Germany to escape Stalin’s regime. They spent five years in German refugee camps before moving to Australia, where they lived for another five years in refugee camps.

Later he studied pure and applied mathematics at the University of Adelaide, and when he wasn’t crunching numbers he was arguing about Sartre and Camus. His education was paid for by the Australian government in exchange for three years’ service, which he fulfilled by working as a programmer of computer simulations (a.k.a. war games) for the Australian Department of Defence in the early ’60s.

This could be why he has always been eerily prescient about technology. During an unpublished 1996 interview, I asked him about the dangers of the then new idea of online advertising. He responded that online ads were a red herring, a minor inconvenience. The insidious danger of the Internet, he thought, would come in the form of data mining. “The ads were the big deal with television and radio,” he said, “but maybe on the Internet the real thing will turn out to be the ability to collect this incredibly in-depth information and get a psychographic profile of exactly who we are and what we’ve done.” He went on to say—and we both laughed—that with the right cookies enabled, porn sites could know more about our own sexual tastes than we did. This was back when most people couldn’t imagine why they would need an email address, if they even knew what one was.

After completing his war games service in 1965, he hopped on a boat to Europe, but it stopped in Japan, and when it set off three days later he had booked a room at the Tokyo YMCA. He soon found a job using his computer skills, as a contractor for Japanese ad agencies. The more advertising work he did, the more disillusioned he became with its amorality. While he was living in Tokyo, a friend introduced him to his future wife, Masako Tominaga, a manager at a bar in the chi-chi Ginza shopping district. In 1970, they married and moved to Vancouver, where he reinvented himself as a documentary filmmaker for the NFB, often in partnership with Schmalz.

Lasn calls Schmalz “his best friend in Canada,” and is quick to credit him with coining the term “adbusters.” The two started out as collaborators at the Adbusters Foundation, but after a year Schmalz pulled back from his day-to-day duties, although he stayed on as “a hands-off co-publisher and occasional adviser, and the cameraman on many of the TV un-commercials we produced,” says Lasn.

In 1973, he and his wife bought the eighty-year-old Edwardian house in Vancouver’s not quite revitalized False Creek neighbourhood that would become the Adbusters headquarters. The offices are in the basement, the entrance hidden behind a collection of bushes and vines, while the top floors are rented out to help fund the revolution. The couple moved out twenty-five years ago; they now live in nearby Aldergrove (a small town best known for its blueberry farms), where they grow their own fruits and vegetables.

Lasn has been criticized for taking credit for other people’s ideas, but it is more accurate to say that he embraces and popularizes them. Even the term “culture jam” was coined by the band Negativland in 1984, but pointing this out is like reminding people that the phrase “Generation X” predates Douglas Coupland’s book—interesting for academics and Trivial Pursuit players, but that’s about it.

He didn’t come up with the idea for Buy Nothing Day, either. The anti-holiday, which exhorts people to cut up their credit cards and protest consumerism in malls around the world, was created in 1992 by Vancouver artist and Adbusters freelancer Ted Dave. He brought Lasn the manifesto and the poster design, and together they devised a meme for it. Dave was not happy when Lasn changed the date from September 24 to Black Friday in November, the start of the US holiday shopping season, but Dave is sanguine about it, writing in a recent email, “Let’s face it, Buy Nothing Day would not have the widespread renown that it has today without the support and promotion of the Adbusters organization.”

One of the qualities that makes Lasn’s lefty radicalism so palatable is his unswerving honesty about his own inconsistencies. The first time we met, he immediately volunteered that he drives a car, owns a TV, and eats Big Macs. “I’m a postmodern contradiction, and I make no apologies for that,” he said. Years later, he remains remarkably consistent in his inconsistencies: “Who is so fucking pure that they escape this hall of mirrors we’re all living in? ” This is his version of Walt Whitman’s “I contain multitudes.”

He is more wary of appearing to focus on the negative. He bridles at the assumption that Adbusters is anti-everything, not just consumerism, preferring to put a positive gloss on the mission: “We are the people who are trying to forge a new way of living, and forge a new culture, to escape the capitalist paradigm that could survive into the future without giving us a 1,000-year dark age. We’re actually incredibly positive.”

Humour also goes a long way toward tempering such grandiose statements, and it has played a large part in Lasn’s success. Adbusters combines the irreverence of Mad magazine, Weird Al Yankovic, and Wacky Packages, transforming parody into a political movement. Ads have featured an emaciated Joe Camel hooked up to an IV in a cancer ward; an Absolut Vodka bottle at impotent half-mast; and branded McBabies. And while Lasn may fill silences with the word “revolution” the way others say “um” or “ya know,” he always manages to come off as more mischievous than threatening.

Amid the World Trade Organization’s historic 1999 Battle in Seattle (a battle predicted in Adbusters), he and three others drove down from Vancouver to join the fray, which was already turning from peaceful protest into city-paralyzing chaos. When a US border guard stopped the rusted-out ’84 Corolla to ask why they wanted to enter the country, Lasn grinned, raised his fist, and shouted, “To protest!” Two of his employees, editors J. B. MacKinnon and Bruce Grierson, braced for body cavity searches, but Lasn kept smiling.

“The guard seemed so stunned by Kalle’s cheerful honesty that he waved us through,” recalls MacKinnon. “A few hours later, we were walking around in clouds of tear gas.”

There is at least one controversy, though, that Lasn hasn’t managed to charm or joke himself out of. It arose from a half-page article buried at the back of the 2004 March-April edition of Adbusters titled “Why Won’t Anyone Say They Are Jewish?,” accompanied by a list naming prominent Jews. Accusations of anti-Semitism quickly followed.

I am Jewish. I don’t believe Lasn knows this. When we talk about the controversy, he doesn’t say anything more contentious than what I would hear from a handful of my Jewish friends talking about Israel. The catch, of course, is context and who is allowed to say what. If a Jew mentions that Natalie Portman is a member of the tribe or that Winona Ryder’s real name is Horowitz, he or she is boasting. If a non-Jew mentions it, I reflexively worry that he is going to don his white hood as soon as it comes back from the cleaners.

Lasn’s list made me queasy, as did Adbusters’ one-page photo essay and storyboard design for an ad to be aired on Israeli TV that drew parallels between Gaza and Warsaw. This prompted the Canadian Jewish Congress (which, like the EU, starts from the premise that drawing a comparison between the Holocaust and anything Israel does is anti-Semitic) to suggest applying pressure to stores that carried the magazine. Shoppers Drug Mart, one of Canada’s biggest magazine retailers, stopped selling it right after the boycott was proposed, though a spokesperson for the chain claimed the CJC campaign was not a factor.

Lasn makes no apologies for the list. He is smart enough to realize that denying being racist just reinforces the perception that you are a racist, so while he is game to defend the politics of the controversial pieces he has no interest in defending himself. He was, however, prepared to argue the point when New York Times columnist David Brooks wrote that the Occupy movement was “sparked by the magazine Adbusters, previously best known for the 2004 essay, ‘Why Won’t Anyone Say They Are Jewish?’ ” When the New York Times edited Lasn’s one-page reply down to two paragraphs, he withdrew it.

Brooks’ backhanded dismissal is telling. Lasn’s impact and accomplishments may be under-recognized and underappreciated because the Adbusters attitude and aesthetic have become so pervasive in activist culture. In 2005, a brilliant parody of a Victoria’s Secret ad helped convince one of the biggest paper consumers on the planet to find a greener paper option. The image of a scantily clad lingerie model holding a chainsaw with the headline “Victoria’s Dirty Secret” was classic Lasn—except it wasn’t Lasn. It was devised in the offices of ForestEthics. Environmentalist Tzeporah Berman, one of the members of the team that brainstormed the ad, says the approach was inspired by Adbusters.

MacKinnon, who created the blockbuster 100-Mile Diet meme with partner and co-author Alisa Smith, was also inspired by Lasn’s ideas, energy, and attitude. In addition to making an impact on the shape of protest, MacKinnon believes Lasn has changed the shape of modern magazines. “He’s a pioneer of the slick subversive. He creates magazines that have a narrative whole, like a film,” he says. “At their best, you can drop in to them at any point and go forward or backward and still have it all make sense. He democratized content, using his readers as a community that supplies its own voice to the magazine, even before that became commonplace on the Internet. Adbusters was essentially a social medium before there was social media.”

Adbusters alumni and contributors include a who’s who of activist writers, but the demographic most influenced by the magazine may be the high school students who dream of shaking up the system. One of those was a mixed-race kid with a black dad and a white mom, and a passion for political change and shit disturbing. No, not the forty-fourth president of the United States, but Micah White. After refusing to stand for the Pledge of Allegiance, the Michigan teen started an atheists’ club at his high school. (He began reading Adbusters around the same time.) Later he wrote an op-ed in the New York Times about the difficulties of forming an atheists’ club at school. White says Culture Jam deeply impacted his development, as did “the magic” of Adbusters. “What we try to do is to spark these epiphanies in the young,” says the thirty-year-old White.

After graduating from university, he contacted Lasn to say he was coming to Vancouver and wanted to intern for the magazine. He conveniently left out that interning at Adbusters was the sole reason he was coming to Vancouver. “The only kind of political activism that seemed revolutionary at all in the English-speaking world was Adbusters. I’m drawn to Adbusters not because it’s a magazine, but because it has the chance to spark Occupy Wall Street,” explains White. He soon became Lasn’s heir apparent, and a key conspirator in planning the Occupy movement. The magazine has since become a launching pad for White’s own memes, such as the term “clicktivism.”

Since his appointment as editor in early 2012, he and Lasn have spent about an hour on the phone every day talking politics and fine-tuning memes. (White now works remotely from his home in Berkeley, California.) “Kalle is one of the few real revolutionaries out there,” he says, echoing Lasn’s thoughts about him. “We brainstorm ideas. One of us will write a first draft, and we’ll send it back and forth in Dropbox. It’s a beautiful collaboration.” When they are culture-jamming on the same frequency, observes Lasn, it’s like a live musical performance.

He sees White less as a protege and more as the guy he would love to storm the Bastille with: “We’re both revolutionary spirits. When we’re on the phone together, we talk revolution. And we mean it.”

Afew months after Lasn suggested that Adbusters storm the ivory tower and break in to the UBC economics department, his team gathered once again around the round table, this time to celebrate his seventieth birthday. In describing his favourite birthday present of 2012, his eyes twinkled with the same excitement exhibited by the boy who gets a BB gun in A Christmas Story. The staff presented him with a group gift: his very own plastic Anonymous mask. Best of all, it came with the news that his collaborators liked the idea of storming UBC’s ivory towers.

Already he was worrying that the Occupy movement had gone mainstream. He wanted to create a new protest meme that would let everybody culture-jam everywhere. His suggested follow-up was #occupymainstreet. Adbusters would urge protesters to attack their local banks with actions ranging from pitching tents and moving in, to staging street theatre, to setting off stink bombs.

“The Zuccotti model has had its day,” he said, “but the spirit of Occupy is still very much alive. Look at what’s happening in Quebec. Look at the media reform movement that’s playing out in Mexico; the education uprising in Chile; the Pussy Riot art activism unnerving Putin in Russia; the new ways of living being pioneered in Greece, Spain, Italy; the hundred youthful riots a day in China; and the Arab Spring still playing out in countries yet to come. Young people everywhere are waking up to a future that does not compute, and if the global economy keeps tanking, if the crisis of capitalism deepens, watch out!”

In Meme Wars, which was published in mid-November, he puts forward some of the ideas Occupy protesters might have championed, to convince future economists to challenge the current orthodoxy (that is, everything they have been taught since Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations in 1776). Editions will be released in Canada, the US, the UK, and Germany, and he hopes they “will put a fire underneath economics students worldwide.”

He knows what he doesn’t want: the current economic system. But he’s not proposing a replacement, because he remains convinced that the best meme will win, and that there will be better memes; and because the media keeps revealing bigger, systemic problems that call for progressively more radical solutions. He has argued for years that economists should work with true costs, calculating environmental impact and health consequences—referred to by classical economists as “externalities.” The recent scandal where Barclays bank was found to be manipulating interest rates now has him wondering if the capitalist system is irreparable.

Several months before the publication of Meme Wars, Lasn was zipping up and down the stairs at the Adbusters office like an intern, not the boss. He stopped briefly to ask one of his young staffers to show me a mock-up of the new book. As she slid a galley proof out of the slipcover, it made a crackling, scratching noise. I couldn’t understand what the sound was until I touched it. The covers were made out of sandpaper. Lasn paused on the stairs to watch me run a finger along the abrasive book jacket, and then he laughed: “That is so it will destroy all of the other books on the shelf next to it.”

Whoops, there go Keynes and Marx.

The book also featured a redesign of the Anonymous mask, just slightly more stylized, to give it the Lasn touch. This one had a smile that was more genuine, happier—as if the mask was laughing.

This appeared in the December 2012 issue.