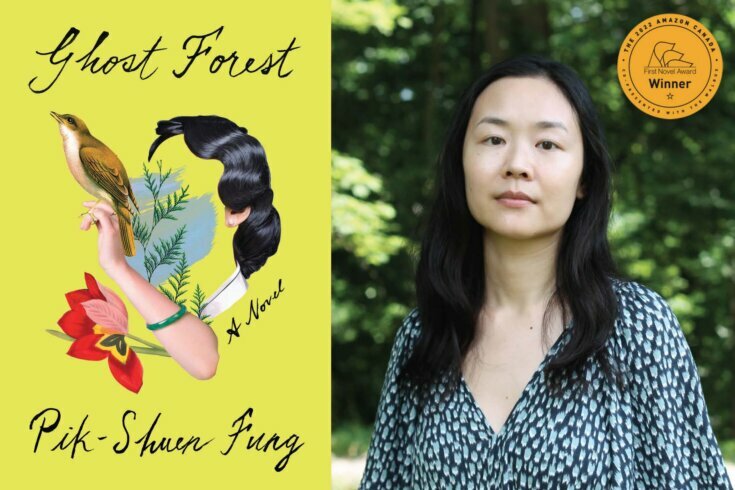

Like many authors, Pik-Shuen Fung was grappling with grief when she began to write. The result is Ghost Forest, a fragmented account of an unnamed narrator’s dream-like attempt to way-find through loss. Fung’s moving portrait of a Chinese-Canadian astronaut family cobbles together threads of memory, light and dark, into one woman’s oral history of loss. Here, the author—winner of this year’s Amazon Canada First Novel Prize—processes a work that helped her process her own life.

—

Your narrator is forced to process the death of her father in the context of her family’s silence. People don’t always find the words for grief; how did you find the words for this book?

I actually started writing this book when I was grieving. It was really important for me to write a book that felt very spacious. Even though grief is such a universal experience, it’s experienced so differently by every single one of us, and every single time is so different. I wanted there to be lots of space for readers to feel their own emotions and draw their own connections as they were reading. That’s why there’s very little interiority of the narrator. That’s also why I wanted to have so much empty space on the pages.

The book focuses on a Chinese-Canadian astronaut family, so you have the existing distance between the protagonist and her father—and then he passes away, creating even more distance.

So much of the story is not only about the loss of her father, but also his absence throughout her entire life. So the grief is for a lifetime of his absence. Then there’s also grief about things that are lost through immigration and through generations. There’s definitely a lot of different distances in the book.

So much of what we know and remember about loved ones who have passed on is constructed from bolstering our narrative with other people’s narratives. How does your narrator craft the story of her father given the influence of her family?

When she’s reflecting on memories of her father, she realizes there are so many questions that she wants to ask him but she doesn’t have the chance anymore. That’s why she turns to her mother and grandmother—to get a fuller picture of their family history. But there’s also a scene near the end of the book when she rediscovers an email that her dad had sent her years ago, one she completely forgot about. In it, he was very encouraging and praised her, which didn’t fit at all with her perception of him as being very critical. She felt she was never good enough for him. I was trying to show that our relationships can still keep evolving and our perceptions keep changing long after loved ones are gone.

Did writing about your narrator’s process inform the ways in which you grieved?

I found grief to be a very dream-like experience. One of the reasons I wrote this book in a non-linear, fragmented way was because I wanted to mimic this experience of how memories are called up through associations of words or sounds or images. I was trying to recreate the feeling of being in a liminal space, and not remembering everything in vivid sensory detail in my own life. My grief was a very intuitive, emotional experience.

There’s a lot of moments in Ghost Forest that try to touch joy. Sometimes, the joy you feel in remembering someone lost brings about the most sadness. How did you navigate that balance in this work?

Even though it’s a book about grief, there’s humour and joy and tenderness in it. It’s not one-note. In the beginning, I thought I was writing a book about grief, and as I was writing, I realized this is also a book about love. It’s also a book about the joy of being alive—and the joy of being able to speak to our family members that are still alive.

Can you share a favourite moment of lightness?

There’s a scene at the hospital, where the two sisters are sitting by their father’s bedside. The narrator asks whether her father would rather have a compliment or a hug, to try to understand what his love language is. He’s obviously not interested at all in the conversation. The sister then asks, “What’s your favourite colour?” And he says brown. I think I was just trying to capture this kind matter-of-fact humour that families enjoy with each other—even in the most difficult and trying times.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE 2022 AMAZON CANADA FIRST NOVEL AWARD WINNER AND ALL OF THE SHORTLISTED AUTHORS AND NOVELS