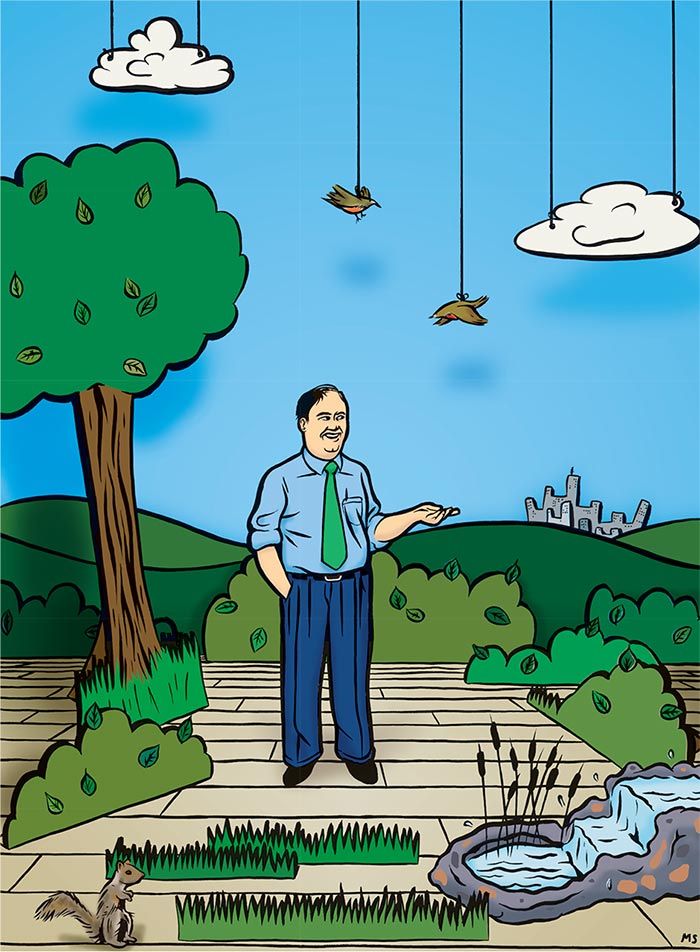

When it comes to branding, the Green Party of Canada is the political equivalent of Coca-Cola. Almost everyone has an image of what the label stands for, mostly cobbled together by exposure, over many years, to media references about Green parties in Europe. They have attracted a significant number of voters by mixing social democratic policies and environmentalism. So encountering Jim Harris, the leader of the Green Party of Canada, can be a bit unsettling. He carefully cultivates a corporate image with his short hair and crisp Tory-blue blazer, and he has a way of speaking that seems far too slick for someone driven by a passion to protect the forests and the creatures living in it. Out on the campaign trail he likes to describe how his concern for the health of the planet arose at Queen’s University in 1985, where, as a student, he learned that a species was going extinct every twenty-five minutes. But that’s about as personal as Harris gets. There are no emotional war stories about his days on the frontlines of the movement—how he jumped in front of a logging truck, put to sea with Greenpeace, or joined in the rescue of a killer whale. Today, the only outward sign that Harris is one of Canada’s most prominent ecowarriors is the car he drives: a $30,000 Prius electric hybrid.

At the beginning of his political life, Harris felt at home in the Progressive Conservative Party. It seemed like a natural fit: his father was well-known in Toronto business circles, and he was educated at Lakefield College School, the institution northeast of Toronto attended by Prince Andrew and sons of wealthy Canadians. But his epiphany at Queen’s eventually weaned him from an obsession with the politics of fiscal restraint, and he formally joined the Green Party in 1989. Even so, he still seems more comfortable around men in pinstripes than young people in hiking boots and rain slickers. In fact, Strategic Advantage, the company he runs out of an office a few blocks from his home in Toronto’s east end, is essentially just Harris working as an inspirational corporate speaker. He has written four business books that dwell at length on leadership, and on his firm’s corporate slogan: “We work to change the world by changing ourselves and by helping our clients change.”

His website boasts a long list of clients, including Mobil and US defence contractor Honeywell, both of which have been the target of environmentalists. The workshops he offers don’t often deal with the ecology or the economics of sustainability. Yet Harris says his work as a corporate cheerleader and his leadership of the Green Party are compatible. “It’s all about change,” he insists. “How do organizations change? How do companies change? The Green Party is all about creating a more sustainable society, and to do that we have to change.”

So how did Harris, a forty-three-year-old businessman who now relies on key advisers who once worked for the Conservatives, take control of the Green Party? And how did he manage to blow out many of the party’s environmental and social democratic principles and replace them with a market-driven agenda while earning the party more than a million dollars in election financing?

The answers have a lot to do with the fact that in 2003 the leadership of the Green Party was available to virtually anyone who wanted to take it over. The membership was disillusioned, the party was broke and had no organizers, functioning structure, or real presence outside of Ontario and British Columbia. Things were so bad that when the interim leader who preceded Harris tried to step down, not a single candidate came forward. For Harris, who was elected party leader in 2003, the move wasn’t so much a hostile takeover as it was a business deal—buying up a franchise that was on the verge of bankruptcy, investing new money and bringing it back to life. Whether the platform stayed true to traditional left-leaning Green values wasn’t the issue. Succeeding at the polls was.

From the perspective of a patron relaxing in the summer sun at an outdoor café, the environment, other than the occasional whiff of exhaust spewing from a passing car, might not appear to be in that bad a shape. But we are living in an age of extinction every bit as profound as the one that led to the disappearance of the dinosaurs about 63 million years ago. According to a British study released last year, the population of many butterfly species has declined by 71 percent in recent years, and bird species by 54 percent.

East-coast fishermen understand the meaning of extinction more than most Canadians after watching the cod fishery collapse in the early 1990s. Now it’s the Inuit of the eastern Arctic who are looking on helplessly as the caribou, a critical source of food, slowly slide into oblivion. Perhaps the most high-profile case is that of the BC spotted owl, which has all but vanished, with only fourteen adult birds left in the province—the only Canadian region in which they are found. Yet British Columbia has no endangered species act, and Ottawa’s toothless Species at Risk Act only covers animals living on federal lands, such as national parks.

So dismal is the situation in Canada that the North American Commission for Economic Cooperation and Development ranked Canada twentyseventh out of thirty industrialized nations in terms of enacting and enforcing laws that reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. This would likely come as a surprise to many, who believe that Canada has environmental laws that are at least stronger than those in the United States. But in May, the Commission for Environmental Cooperation of North America—a nafta watchdog group—reported that while the United States was making progress on environmental pollution, Canada was falling behind. And late last year Johanne Gélinas, Canada’s commissioner of Environment and Sustainable Development, wrote a scathing report in which she concluded that Ottawa’s failure to take stronger action on the environment reflects a “lack of leadership, lack of priority, and lack of will.”

Given the sorry state of Canada’s environment, the Green Party’s electoral success—winning 4 .3 percent of the popular vote—would seem understandable. Yet on the whole, environmental groups have largely failed in their efforts to influence government policy. In the United States, the inability of environmentalists to effect real change prompted what would become a widely debated article by Michael Shellenberger, an activist, and Ted Nordhaus, a pollster, called “The Death of Environmentalism.” The article, presented to the Environmental Grantmakers Association in 2004, argues that the movement has become divorced from larger issues of broad public significance and, as a result, “the environmental community’s narrow definition of its self-interests… undermines its power.” The article has not only led to deep divisions in the US movement, but it has also illustrated differences among Canadian environmentalists on how to force Ottawa to halt ecological decline.

Because of its success, it might seem logical that the Green Party would be the electoral arm of the environmental movement in Canada. But according to Elizabeth May, executive director of the Sierra Club of Canada, there is virtually no relationship between environmental organizations and the Green Party. “It’s not a movement that’s prone to say ‘ How do we enhance our political power base? Maybe we should have our own party.’ I mean, that kind of conversation doesn’t ever happen in the environmental movement.” Most of the country’s 2,000 environmental organizations don’t even see themselves as lobby groups, says May, with “maybe a dozen ever meeting with an MP.”

In other countries, especially in Europe, Green parties have attempted to achieve political power by broadening their definition of “environmental” to include foreign policy, and social and economic issues. Last year in Rome, Green parties from thirty-two countries found enough common ground among their diverse memberships to form the European Green Party. Working together, they established a single platform and managed to capture thirty-five seats of the 624-member European Parliament in the June 2004 election. While not as radical as many of its federated members would like, the European Green Party’s policies are still broadly socially democratic and critical of corporate globalization. The party also calls for a guaranteed minimum income across Europe, a ban on all genetically modified organisms (gmos), and making manufacturers responsible for the entire lifecycle of their products.

By comparison, the Green Party in the United States is unambiguous about its left-wing political stance. It has both a black and a women’s caucus. If elected, it would withdraw the United States from nato and norad and from all free-trade agreements. It also calls for a full month’s vacation time for all workers each year, and for removing the words “under God” from the Pledge of Allegiance. This relatively consistent left tilt distinguishes the Green Party of Canada as one of the few national Green parties—the German Greens are probably closest ideologically—in the developed world to have moved to the right politically. And unlike Europe’s unified Green Party, there is virtually no communication between the party in Canada and its more radical counterpart in the United States.

The conservative positioning of the party under Harris may also explain its unusual approach to policy development. Members can comment on party policies on a website but those policies are actually determined by the national office. There has been no formal policy convention, nor does the party rely closely on the expertise of environmental organizations. “We pretty much get asked by all the parties to comment on their environmental policies, certainly by the ndp and the Liberals,” says May. Leading up to the 2004 election, she told Harris: “‘If you want a more detailed, robust platform, feel free to ask in the coming months.’ We never got any pickup on that [offer].” But when the Sierra Club came out with its report card favouring the ndp, says May, Harris called them ndp hacks.

Harris may simply have disagreed with the political bent of the Sierra Club’s policies. According to Nelson Wiseman, a professor of political science at the University of Toronto: “In Germany the position of the Green Party has shifted from being radical to almost mainstream. That’s the challenge facing the Green Party of Canada. And [Harris’s] shift to the right is seen as a way of gaining increased credibility, so as not to be seen as the dope-smoking fringe.”

In the process of mainstreaming policy, Harris has driven many traditional Greens from the party, who, from his perspective, would have happily remained on the political fringe rather than abandon their cherished left-wing policies. There are some in the party still opposed to Harris, but many others—especially in Ontario and Alberta—support his eco-capitalist solutions. In the simplest analysis, Harris would end subsidies to polluting industries, such as tax breaks for oil companies, and redirect the money to social programs and initiatives to dramatically increase energy efficiency. Harris rejects the heavy hand of government intervention in the belief that if consumers are given environmentally correct options, they will make decisions that will change corporate behaviour. One of his strongest supporters outside of the party is Wayne Roberts, a prominent Toronto environmentalist and co-author of Get a Life: A Green Cure For Canada’s Economic Blues. According to Roberts, Harris has always been interested in the economics of the environmental movement. “This accounts for his desire to mainstream the Greens,” explains Roberts, “which many holier-than-thou types equate with being moderate or right wing. But in his gut instincts he is a Green, in the same way most ndpers have a gut instinct for the disadvantaged.”

As Harris geared up to take control of the party in 2003, he was preoccupied with new election finance legislation, which he believed would boost the party’s chances for a breakthrough. Prime Minister Jean Chrétien’s government had introduced Bill C-24, legislation changing how parties could raise money for elections. Out were major donations from corporations and trade unions. In was government funding based on the number of votes parties received in the previous election —$1.75 per vote. To earn this, a party had to get at least 2 percent of the popular vote. To ensure the party received the money, Harris was determined to have the names of Green Party candidates on the ballot in all 308 federal ridings, whether, it seemed, they knew anything about the party’s policies or not.

In his first leader’s memo to the party’s newly elected council in 2003, Harris outlined Ottawa’s new election financing legislation and how important it was. Much of the 5 ,000-word priorities document dealt with C-24 and the all-consuming importance of running 308 candidates. In contrast, there was almost no mention of policy development. “I was concerned with the obsession with getting 2 percent of the vote,” recalls Matthew Pollesel, a former Green Party staffer. “That’s all they talked about.”

Early in his leadership, Harris clearly demonstrated that almost anyone persistently opposing him would be driven off the party’s governing council. The first to experience this was Julian West, a prominent environmentalist and Green Party stalwart from British Columbia. West found himself on the wrong side of Harris when he became involved in a discussion of a plan to ensure the vote wasn’t split between the Green Party and the ndp, which also had a strong environmental platform. Under that proposal, which was never put into action, the Greens would have adopted a non-compete policy in the many urban ridings in which the ndp could do well.

To remove West, Harris called members of the party’s governing council and lobbied them to get rid of his critics. Recalled Gretchen Schwarz, a long-time Green Party activist from Ottawa, and chair of the council at the time: “Before he was even elected, Harris phoned me up and said, ‘We have to get West off council.’ I was just stunned and said, ‘What? ’ Harris said, ‘Well [BC leader] Adriane Carr wants him off council, and I promised her that I would deliver that for her if she would support me in my leadership campaign.’” Harris denies the allegation. But whatever actually happened behind the scenes, West eventually quit in frustration. Harris usually had his way. “Jim has a very fine gift for making people sick of fighting ,” recalls Schwarz, who also left the party. “He’s a salesman. He’ll make you throw up your hands and say, ‘Take my house, take my kids, I don’t care, leave me the heck alone.’”

In February 2005 , Kate Holloway, the party’s fundraising chair, was suspended from the council, and Platform Chair Michael Pilling was fired. They were preceded over the two years of Harris’s leadership by a number of others who either quit the council or left the party altogether. Some of those have now formed the rival Peace and Ecology Party. “I had a gut feeling about this man,” says Schwarz. “He wasn’t Green. He wasn’t passionate about saving the planet. He was saying lines and speaking a part like an actor.” But the party was desperate for someone with organizational skills, and she admits, “I thought we could use him. I might not want to sit down and have a beer with Harris, but he had something that we didn’t have.”

Once in charge, Harris knew he would quickly have to raise money to invest in the looming federal election campaign. One plan, called “affinity funding,” involved such organizations as the Humewood Ratepayers Association, a Toronto citizens’ group. Essentially, the party would lend its legal authority to issue tax receipts for political donations. Groups such as Humewood would then kick back a percentage of the money raised to the party. To test the legality of the affinity plan, members of the council—against Harris’s wishes—had it vetted by Elections Canada, which found it illegal. Another scheme called “democracy bonds,” which was never adopted, would have paid investors 25-percent interest, but the loans would only have been paid back if the party received more than 2 percent of the vote.

Despite internal bickering over fund-raising, Harris finally received the money he needed to pursue his 2-percent solution from two unlikely sources. The first was wealthy Toronto feminist and former Tory candidate Nancy Jackman (now Nancy Ruth), who donated $50,000 to the party. According to Ruth, who was appointed to the Senate in March, she met Harris when she ran against him in a 1993 provincial by-election in Toronto. They became friends and she agreed to help. “I wanted them,” recalls Ruth, “to have a chance to get the $1.75 per vote.” Critical support also came from wealthy BC businessman and Green benefactor Wayne Crookes, who loaned the party more than $300,000. In the end, even his fiercest critics were stunned by Harris’s ability to field a full slate of candidates. “It totally staggered me,” recalls West, “that they could get 150 signatures [per candidate], in most cases in ridings where they had no active members.” And as unlikely as the whole project was, Harris’s strategy worked. And not at just the 2-percent threshold: 4 .3 percent, or 582,247 Canadians, voted for the party. Under Bill C-24, this translated into $1,018,932 of government funding and the promise of building a party that could do even better in the future.

As Harris established himself as leader, he began a pattern of hand-picking people to work with, even if that meant going outside of the organization. One was Pilling, whom he put in charge of policy while he was allegedly still working for Strategic Advantage. Another was David Scrymgeour, former national director of the Progressive Conservative Party. He had been at the heart of a conflict leading up to the Conservative leadership convention in 2003, when Conservative MP Peter MacKay was chosen to head the party. The controversy centred on claims by David Orchard, who was also running for the leadership, that Scrymgeour had used a variety of dirty tricks to ensure that Orchard’s supporters were denied delegate status. Harris, aware of the controversy, phoned Orchard, whom he had earlier courted—unsuccessfuly—for electoral support. “We talked for quite a while,” recalled Orchard, “but he didn’t follow up on any of [my advice]. He didn’t get rid of him.”

The arrival of strategists such as Scrymgeour—and another controversial former Conservative/Alliance operative, lawyer Tom Jarmyn—stood in sharp contrast to previous Green Party leaders, especially those such as British Columbia’s Joan Russow, who were preoccupied with policy matters. An environmentalist and social demo-crat with a Ph.D. in interdisciplinary studies, Russow compiled a 400-page policy backgrounder for the party as leader. But in looking at the party’s platform today, she wonders how the planks she built around social democratic policy and strong regulatory enforcement were replaced by a structure that she says could lead to the adoption of right-wing programs. Said Russow: “It has abandoned itself as a principlebased party.”

According to Harris, Russow’s recommendations were replaced with a platform developed directly by the membership and one more appealing to voters. Many of the party’s economic policies appear to be mainstream—even, at times, identical to those of the Conservatives or Liberals, including promises to “lower taxes on income, profit and investment.” The idea of a guaranteed annual income has been removed from the platform. Poverty rates a mention, but there is nothing specifically proposed to address the root causes of the problem. Instead, the Greens promise to “enhance the existing network of food share, school nutrition, and food bank programs to eliminate hunger and malnutrition.”

Like Conservative leader Stephen Harper, Harris wants to hollow out Ottawa with a massive devolution of power. According to its own literature, the Green Party would “respect the right of provinces to ‘opt out’ of federal initiatives without financial penalty.” This would undermine the Canada Health Act and make creation of new national social programs all but impossible. Some policy language even echoes the old hard-right Reform Party. For example, in a midelection news release, Harris stated: “Tossing money alone at health care is not going to miraculously fix the problems faced by older Canadians.” Instead, he proposed supporting health care through more community volunteerism.

Harris even watered down the party’s policy on genetically modified foods, from one calling for a ban to one simply calling for labelling. Harris personally opposes the manufacture of gmo foods, but when asked why he stopped short of calling for a ban, he replies: “I want them labelled but we don’t even have labelling. What’s the point of calling for banning when we’re eating the stuff, and we don’t even know it? ” Instead, Harris would rely on the eco-capitalism market solutions that inform so much of the party’s platform, arguing that consumer disapproval of products, not a government ban, will ultimately change corporate behaviour.

Harris’s desire to create a consensus on the environment by building bridges to the corporate sector emerges when asked whether the party would increase the level of fines against polluting corporations. “It’s not about being punitive,” he insists. “People want to do a good job. And I work with people who are in corporations, and they’re good people. They have children, and they care about their future too.”

Even so, there are occasional and dramatic contradictions to the conservative thrust of the platform that seem designed to appeal to radicals in the party. For instance, the party promises to “rescind all uranium-mining permits and prohibit the export of fissionable nuclear material.”

During the 2004 election, the party was found wanting in the two areas in which Greens feel they can make a difference—promoting democracy and protecting the environment. Democracy Watch, an Ottawa-based group, gave the Greens a D− for not adequately addressing issues surrounding corporate responsibility and ethical government. And on the their environmental policies, the ndp received a slightly higher grade than the Green Party from both the Sierra Club and Greenpeace.

In the end, however, questions surrounding policy didn’t matter much in the election, because many of the candidates (and voters) weren’t aware of Harris’s revamped platform anyway. At least a third of the candidates, says Pollesel, didn’t even live in the ridings in which they ran. And like some candidates, Marc Loiselle from Saskatoon, who ran in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, says that he was “not that familiar with actual Green policies.” When he did speak publicly, he put forward what he thought the party’s policies should be, not what they actually were.

Not only were policies not that important. Neither was political experience. Recalls Pollesel, who had worked for half a dozen MPs and was the most experienced organizer on the election team: “It was so off-the-wall. You had a policy director who didn’t know anything about policy, a leader who doesn’t have a clue about politics, and a media guy who doesn’t want to talk to the media. It was the antithesis of everything a real party should be.” (Pollesel eventually filed a complaint with Elections Canada listing fourteen violations of the Elections Act.)

For a party that had just made a breakthrough of historic proportions, the Green Party convention in August 2004 was hardly a celebratory affair. Only about 180 party members showed up out of a membership of around 3,800. Just 956 bothered to mail in ballots, and Harris won with just 54.8 percent of the vote. Still, Harris immediately tightened his hold on the party by assigning Scrymgeour the task of developing a new organizational structure that would make the Greens even more mainstream. Scrymgeour’s subsequent report, “Green and Growing,” was full of the scientific manipulation of the electorate common to the Conservatives and Liberals, but anathema to traditional Green values. His reference to “high yield edas” (riding associations) sounded more like a mutual fund promotion, and identifying “benchmarks and best practices” was right out of a corporate governance manual.

On Scrymgeour’s advice, Harris created an election-readiness committee. Consisting of Harris, party creditor Wayne Crookes, selected staff members, and loyalists from the party’s elected council—all men after the lone woman quit—it has allowed Harris to run the party while often circumventing the governing council and its messy disagreements. And that has helped him to weather the storms around his leadership style—for now.

It is hard to predict what will happen to the Green Party under Harris, and whether it will make a breakthrough as the German Greens did. But Stuart Parker, who led the BC Green Party for seven years, shared an insight into Green Party culture, one that might give Harris pause. “Most Greens believe that it is actually wrong to have a strong leader,” said Parker, “so they can only have one of two relationships with their leader. Either this leader is so great that they transcend the inherent evils of ‘leadership,’ in which case they should be deferred to, or their leader is somebody who has seized control and is corruptly operating the party.” If Parker is right, Harris might find himself reflecting on the advice he offers his corporate clients in his book The Learning Paradox: “[T]he more leaders cling to power, the less powerful their organizations are. The more they control, the more out of control their organizations.”