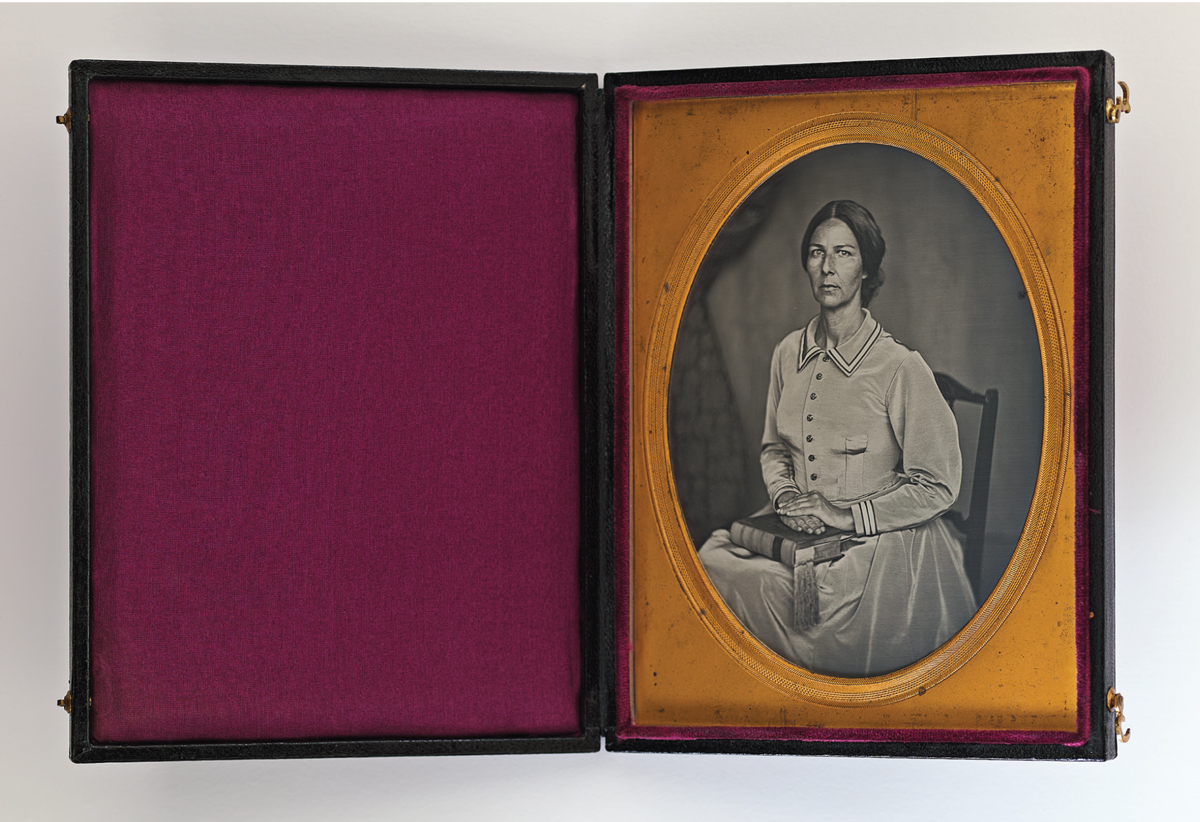

DURING THE 1860s, British painter Frances Anne Hopkins accompanied her husband, a high-ranking official with the Hudson’s Bay Company, on at least three excursions with voyageurs. Hopkins sketched the daily life of the fur traders and, upon her return to England, produced large-scale oil paintings whose accuracy provides an unparalleled glimpse into this chapter of Canadian history. Despite exhibiting at the Royal Academy of Arts, in London, she always signed her work “fah”—effectively concealing her identity in a male-dominated art world that typically excluded women.

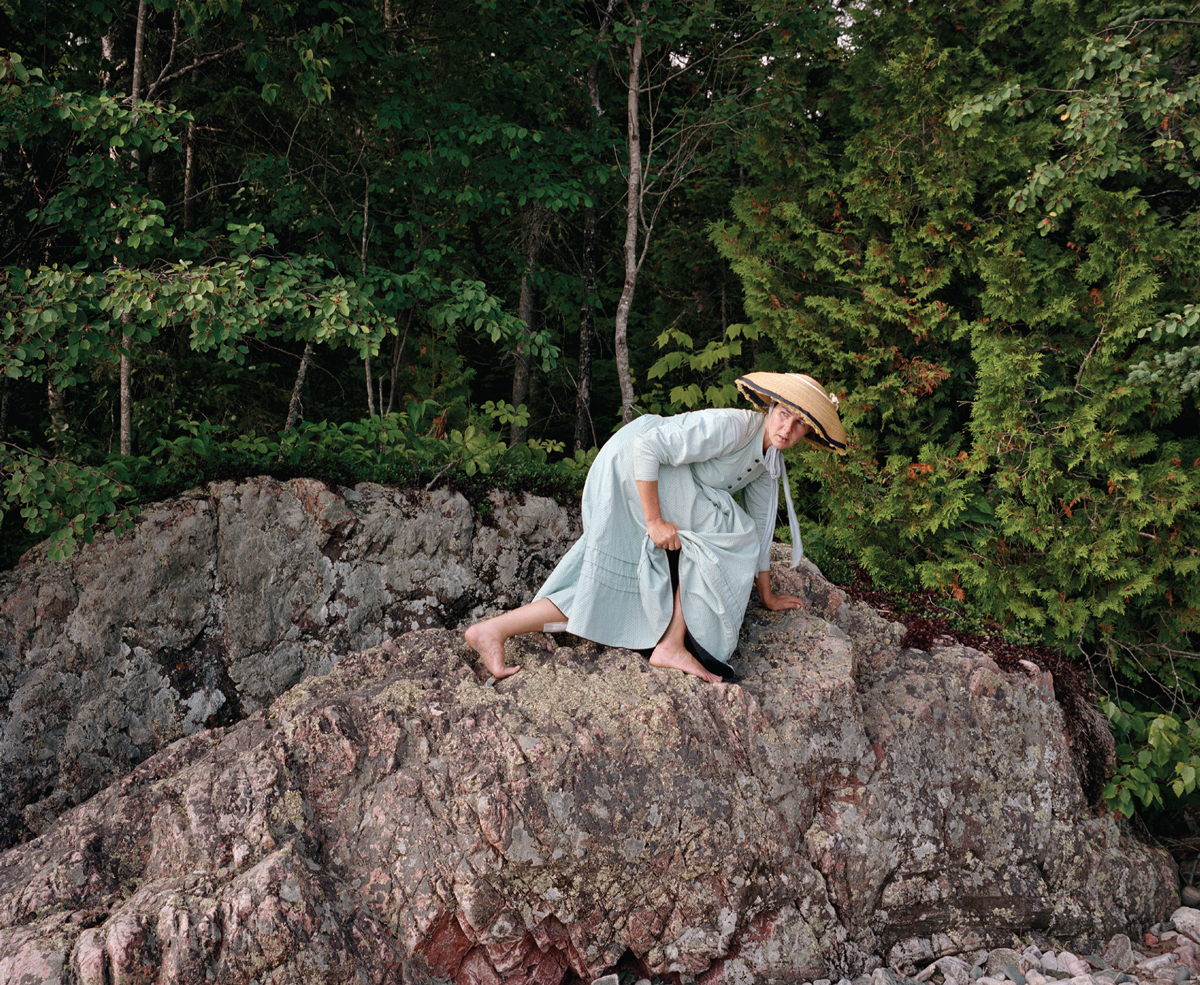

In the summer of 2018, I decided to channel Hopkins on my own odyssey. Dressed in nineteenth century period costume, I embarked on a seventy-day canoe trip along the fur traders’ route in Ontario. Using Hopkins’s paintings and sketchbooks as a starting point, I recreated her final, 1869 voyage in reverse: from Lachine, Quebec, to Fort William, Ontario. Accompanied by a guide, I paddled, portaged, and did many of the daily chores needed to make camp. I’ve always been drawn to documentary projects. In 2011, I drove for four months, coast to coast, to rediscover my roots. In 2017, I set out across the United States to chronicle Donald Trump’s first 100 days in office.

This time, my ambitions hit closer to home: to explore what it meant to be a female artist during the nineteenth century as part of a wider investigation into my own career. As a middle-aged woman, I increasingly experience a sense of disappearing—not just from the art world but from society. We exalt the young and beautiful in popular culture, and this celebration of youth is further reinforced in our art. Female mid-career artists face not only gender disparity but also ageism.

I felt a profound affinity with Hopkins, who, balancing the roles of wife and mother while navigating the choppy waters of a patriarchal society, persevered in her practice. The trips couldn’t have been easy. An upper-class European woman, Hopkins likely didn’t portage or do any of the physical work necessary to set up camp. Still, she must have had a terribly difficult time, dealing with blackflies, orchestrating getting in and out of birchbark canoes, and sleeping in tents.

Using a variety of photographic practices, I set out to experience what she had, creating a mythological world where I cross in and out of her life. She often painted her husband and herself in the canoe. Likewise, with Hopkins as my muse, I created self-portraits. By intertwining my adventure with her biography, I hoped to create a new vision of Hopkins—and of myself.

I, Voyageur . . . In Search of Frances Anne Hopkins was funded by the Canada Council for the Arts’ New Chapter Program.