In 2005, Kirsten Stevens’ forty-year-old husband, Dave, died when the float plane flying him to work at a logging camp crashed in the waters off northern Vancouver Island, killing everyone on board. She became an advocate for higher Canadian aviation safety standards, eventually joining forces with Hugh Danford, a former pilot and Transport Canada civil aviation inspector turned whistle-blower. The two featured prominently in my November 2009 article, “Fly at Your Own Risk.”

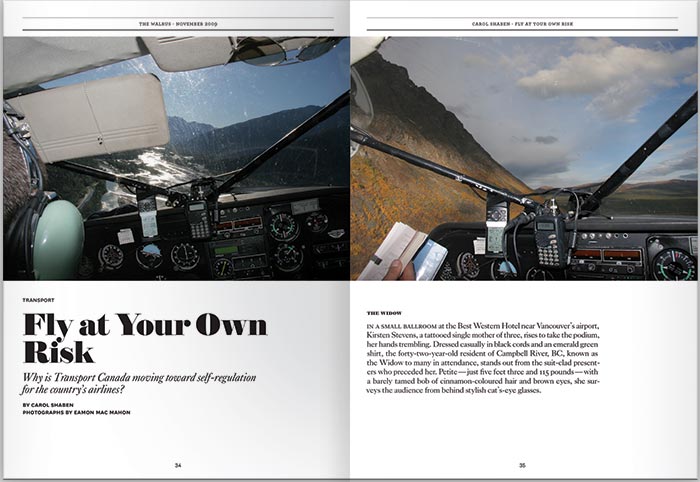

At the story’s heart was the Safety Management Systems initiative, which shifts responsibility for developing and monitoring safety compliance from the government to airlines. When I began investigating, Transport Canada had implemented SMS among large commercial airlines, and was moving toward self-regulation for 600 smaller carriers (including air taxis and commuter airlines) and maintenance organizations. Serving as feeders for major airlines, ferrying workers and freight, these operators connect thousands of Canadians to larger centres, and deliver supplies and medical support to remote communities.

Stevens, Danford, and others had warned of potentially lethal consequences: small airlines have fewer resources and face greater risks than large ones. Introducing self-regulation in a sector that experiences a disproportionate number of accidents, and where oversight was already seen as lax, was akin to putting the fox in charge of the henhouse. A 2008 Auditor General’s report noted that during the transition to SMS, Transport Canada did not document risks or suggest mitigating actions. Nor could the government demonstrate that it had a national mechanism to consistently monitor safety oversight, or that it employed enough qualified inspectors and engineers to do so.

So what has changed since then? Sadly, when it comes to small commercial operators, very little. Last spring, another Auditor General’s report found that despite a “rigorous aviation safety regulatory framework,” in some cases it took Transport Canada more than ten years to identify and address emerging safety issues. It also noted that “for most large air carriers and maintenance organizations and for small air carriers and maintenance organizations, Transport Canada is missing key risk information and has no formal process in place to collect that data.” In 2010–11, the agency completed only two-thirds of planned inspections, and most did not follow an established methodology with appropriate management. Plus, it still had not recruited or trained enough inspectors and engineers.

Many experts believe SMS can help aviation companies develop effective safety systems—but not without government oversight. For now, Transport Canada has put SMS implementation on hold among smaller operators, yet they raise the greatest concern: from 2002 to 2011, they accounted for 91 percent of all commercial aircraft accidents and 93 percent of fatalities.

“I can see some progress when it comes to safety in the float plane industry,” Stevens told me recently, proud of her success in pushing for recommendations that mandate better emergency exits, and personal flotation devices for float plane passengers and crew. But she added that Transport Canada continues to reduce oversight for small operators.

She has had to pull back from her advocacy work due to health issues. Last December, she let go of something she had held on to for almost a decade: the serial plate from her husband’s salvaged airplane. She mailed it across the country to Hugh Danford, to thank him for his support. He calls the plate a treasure from the deep. “I don’t consider it mine,” he told me. “It’s on loan, and it’s an inspiration to carry on.”

This appeared in the April 2013 issue.