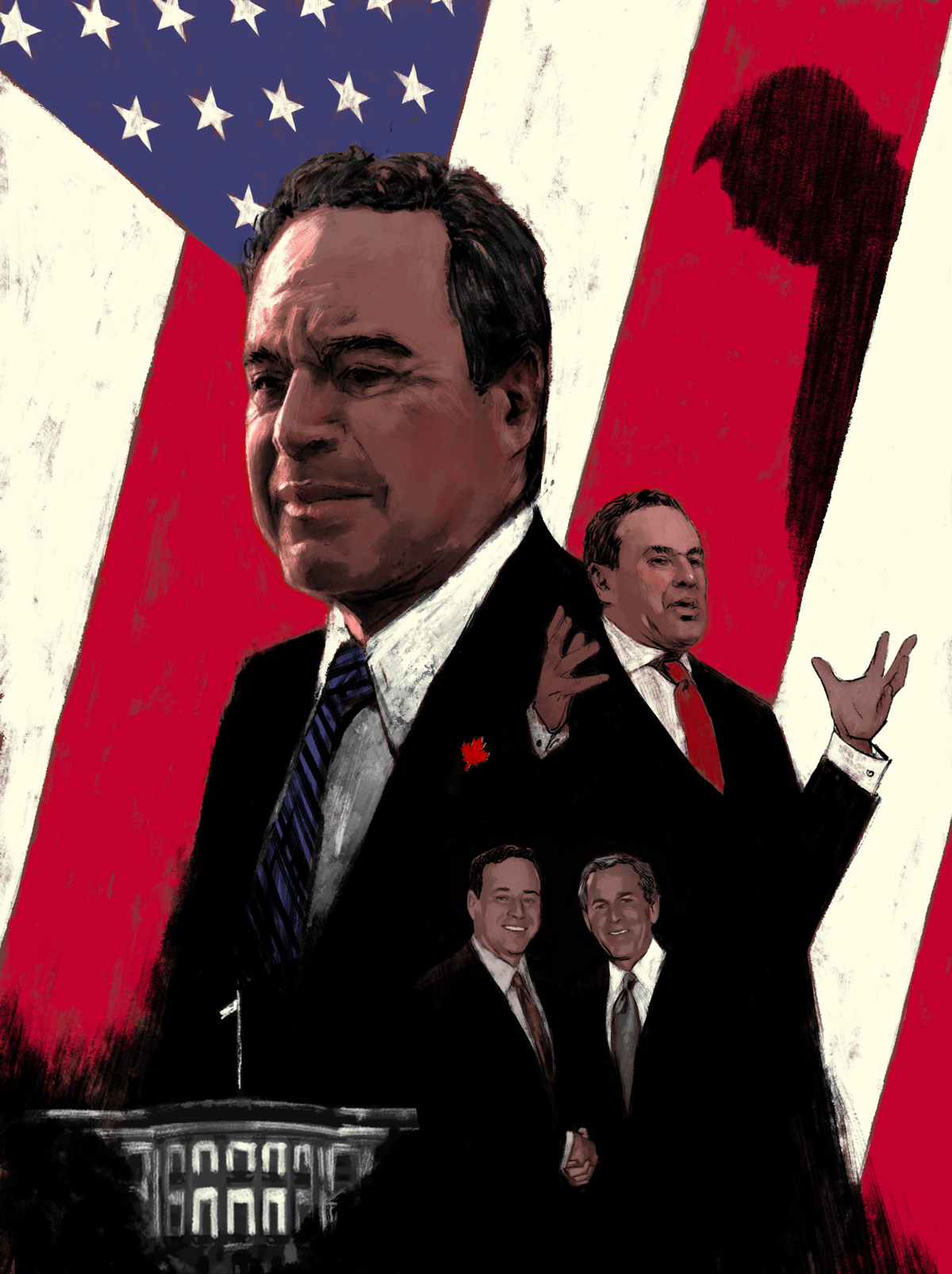

On the evening of November 2, 2018, a Munk Debate took place at Toronto’s Roy Thomson Hall arguing the proposition that the future of Western politics is populist, not liberal. As the beginning drew near, protests erupted in front of the venue because the organizers had chosen Steve Bannon—architect of the Trump campaign, former leader of the alt-right Breitbart empire, Svengali to apprenticing authoritarians, and the world’s foremost proponent of the slept-in blazer—to argue on behalf of populism. But commentators were also aghast at the person tasked with defending the values of classical liberalism: David Frum. Yes, that David Frum: the Axis of Evil neocon who served in the George W. Bush White House, boisterously supported the Iraq War, and authored a handful of books advocating hardline conservative policies.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Not, in other words, the kind of CV that shouts out “defender of liberal values.” “When it’s left to David Frum to hold the line against Steve Bannon . . . ” Naomi Klein tweeted, “these Munk Debates are a disgrace.”

The event was held up for over half an hour due to the commotion outside the entrance. There were some minor skirmishes, multiple arrests. Inside, someone unveiled a banner that read, “No hate. No bigotry. No place for Bannon’s white supremacy.” Bannon grinned at the spectacle. Frum sat, patient and bemused. Once underway, the moderator began to explain the scoring method. The crowd would vote now and again at the end of the evening with provided clickers. The debate could finally begin.

As the evening progressed, Bannon found various ways to say that populism was about the people, not about authoritarianism; Frum found various ways to say that liberal democracy was responsible for most of society’s major advances of the last three centuries. There was some engagement and the occasional direct rebuttal, but it was mostly a mild affair: two men expressing different world views. There was no animosity, little tension, and in fact, Bannon consistently expressed his admiration for Frum’s insight, compliments that were off-putting in their own right. Having Steve Bannon praise your intellect is like having Dracula admire your shirt collar.

After about eighty minutes of speeches, the debate was over. It was up to the audience now. After a few minutes of tabulating the results, the numbers popped up on the giant screen behind the participants. There was an audible gasp. At the beginning of the debate, 72 percent of attendees had disagreed with the proposition that populism would soon supplant liberalism. After they heard both sides, that figure dropped to 57 percent—Frum, defender of liberal democracy, had somehow managed to lose much of the room. Audience members were open mouthed. Frum seemed stunned. Bannon, quite graciously, said, “If we don’t convert people of the stature of David Frum into our movement as the public intellectuals, we’re not going to have a movement.” Frum congratulated Bannon: “As in 2016, the rural vote came in.”

It wasn’t until later that night, long after the results had rippled through social media, that the Munk team posted a mea culpa online. Due to a technical glitch, they had gotten the numbers wrong: 72 percent of the crowd had still not supported the proposition. Either way, it remained a win for Bannon—his alt-right acolytes simply claimed another example of the left rewriting history to suit its own ends.

There were many possible conclusions to be drawn from the Munk affair: that, after all the effort, no minds were changed; that the organizers had lost the data and tried to fudge it; that the whole thing had been a charade anyway since Frum made the mistake of taking the debate seriously whereas Bannon seemed to treat it like a lark. But lost amid the debacle was maybe the most important takeaway of all: the event revealed the nearly complete evolution of David Frum. The man who played as prominent a role in American politics as any Canadian likely ever has—and as a Republican, no less—had returned home to cement the growing understanding that he is no longer a reactionary warmonger (admittedly my own read for many years) but is in fact a thinker of centrist and even certain left-leaning positions: a convert to war skepticism, a proclaimed internationalist, a supporter of universal health care, a believer in same-sex marriage, an upholder of the role of government, and most prominently, one of the few leading Republicans who was willing to pay the price to say, loudly and often, that Donald Trump is a craven, amoral, criminal, empty, narcissistic, inept liar. Which, as the 2020 election season moves into the almost-can’t-bear-to-watch phase, makes Frum the most consistent and insightful conservative interpreting what’s happening. In fact, other than the immigration file, on which Frum remains something of a restrictionist, it may seem fair to conclude he’s now an out-and-out liberal. Which really leaves only one question: How the hell did that happen?

The children of famous parents evolve in various ways. Some retreat entirely, forging private lives. Some struggle to find themselves. Others become minor replicas of their famous progenitors. Then there are those like Frum and his senator sister, Linda, who become parent adjacent, putting down career roots on a different street in the same neighbourhood. Frum’s mother, Barbara, died in 1992, at the age of fifty-four, from chronic leukemia. It is probably difficult for a younger audience to properly contextualize the influence and reach she possessed in the later decades of her life. After hosting the CBC Radio program As It Happens, which she started doing in 1971, she moved to television in 1982 and hosted The Journal, which, following The National each night, offered more in-depth reporting and narrative, a kind of daily 60 Minutes. It was during this period that she became a household figure in Canada, famous for her fearless reporting and professional manner that occasionally allowed for a grin or a chuckle.

But only occasionally. Her persona as a tough interviewer was so entrenched that the Maritime comedy show Codco ran a segment, called “The Jugular,” in which Greg Malone, impersonating Barbara, interrogated hapless guests so as to draw out their pain and bitterness. She was such a good sport about the joke that she and Malone, in drag as Barbara, presented together at the Gemini Awards one year. Canada’s Sesame Street even created a Muppet based on her, known as Barbara Plum. She was, in the days when there were few television channels and no widespread internet, not just omnipresent but universally respected in a way that seems impossible in today’s takedown culture. It felt appropriate that her memorial was broadcast on CBC TV, as if it were a state affair.

Barbara Frum may have been an icon, but she was also a mother and a wife. It was a strangely splintered upbringing for young David in that he had a famous (and imposing) mother and a wealthy (and genial) real estate developer father, yet death and mortality hung over the house every day. Frum’s father, Murray, was born in 1931, the year after his family came to Canada from Poland. The extended family remained behind, and almost every single member, on both sides, was murdered in the Holocaust. And, though hardly anyone knew it at the time, Barbara was first diagnosed with cancer and told she had one or two years to live in 1974, when she was thirty-seven and her son fourteen.

“We had a happy household in so many ways,” Frum told me by phone from his home in Washington, DC. “But that sense of things just off to stage left and stage right, of doom and danger around the corner, that was really a formative thing. Barbara had many sayings that we still quote, and one of them was, ‘There are those who know and those who don’t know,’ and what she meant by that was the knowledge of the potential for tragedy in human life, of loss, and just how near the surface loss and suffering are. That statement, which I didn’t appreciate enough when I was young, becomes more powerful as you go through life. You wanted to be one of those who knew, not one of those who didn’t know.”

There were other things Frum felt he came to know. It was in his mid-teens that he had his political “road to Damascus” moment. In the summer of 1975, he got a job working on the election campaign for a Toronto NDP candidate. It was also the summer that his mother gave him a copy of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago. As he trundled back and forth on transit—home to work, work to home—he read the book’s devastating indictment of the Soviet Union and its vast prison system. Frum was overtaken by a sense that the westernized left, which he saw as sympathizing with radical movements, had the world wrong. “It had this overpowering effect on me,” Frum told The Nation in 2012. He finished his placement, but reading Solzhenitsyn’s book instigated a reaction against the ideologies of the left, nascent and unformed as his belief still was then.

After high school, Frum went to Yale, where he pursued a simultaneous BA and MA in history. To most, it would seem a peak experience, but Frum doesn’t quite remember it that way. “I was clever in the sense of being pretty well-informed and verbally deft but also missing large dimensions of human wisdom. I was a very serious-minded young person. But I lacked things. There are so many things that I should have understood that I didn’t.”

Such as?

He paused, seemed to prepare an answer, but drew back. “Oh, I don’t know. But I was a hard worker. I really wanted to learn. And one of the things that we were all always told, as undergraduates, was that so many of your most valuable experiences here will happen outside of the library. And yet, for me, the most valuable experiences I had at college mostly happened inside the library.”

Following his graduation, he returned to Toronto, where, he said, he spent 1982 to 1984 “floundering.” He fell into a young-man-without-a-plan malaise that his mother finally addressed when she told him that, if he couldn’t decide on his future, she’d create one for him. Her vision started with law school, which Frum was not keen on. Barbara implored him to take the LSAT. He bought a sample test and scored seven out of twenty-two, which he used as evidence that law school was not in his genes. Dismissing his argument, Barbara took the same test and scored a perfect twenty-two.

“She had such a precise mind, and I guess I interpreted her score as a dare or a challenge, so I took the book back and worked on the sample tests until I could get twenty-two out of twenty-two, at which point, of course, she said I therefore had no excuse not to take the actual test. And then, once you write the actual test, it’s an escalator you can’t jump off.”

He attended Harvard Law School, where he also became more active politically, serving as president of the Federalist Society chapter, a conservative and libertarian law students’ group. Upon graduating, he met budding journalist Danielle Crittenden (in 1987, at a party hosted by his mother in their Toronto home). The two got married, and Frum soon joined the editorial page of the Wall Street Journal and began vigorously inserting himself and his ideas into American politics.

Frum released his first book, 1994’s Dead Right, halfway into Bill Clinton’s first term. It was billed as a young conservative’s plan to rejuvenate the Grand Old Party by breaking free from its misguided post-Reagan preoccupations with culture-war targets (race, nationality, sex) and instead focusing on its traditional goals (business, small government, lower taxes). George Will, the éminence grise of the American right, said it was “as slender as a stiletto and as cutting.” Frank Rich, writing for the New York Times, called it “the smartest book written from the inside about the American conservative movement.”

The book marked Frum as an important new voice, especially for his willingness to say things other conservatives didn’t particularly want to hear, which became a pattern. During the remainder of the Clinton years, Frum continued to promote a politics focused on policy over ideology, but his was a conservatism that lost momentum as Newt Gingrich became the dominant Republican on Capitol Hill. Gingrich led a nasty and highly partisan rearguard culture war, a good part of which was focused on the morals, or lack thereof, of a Clinton gripped by a sex scandal. (It would later emerge that Gingrich himself was having an affair with a young aide during the same period.) However, when George W. Bush won the 2000 election, he did so after campaigning on a “compassionate conservatism” that distanced itself from Gingrich’s bellicose ways. Shortly thereafter, Frum, seemingly vindicated, was invited to join the White House as part of the president’s speech-writing team. It was a heady time for a Canadian who’d just had his fortieth birthday and who had moved to Washington from Toronto only in 1996. Frum was not Bush’s primary speechwriter—that role fell to Michael Gerson—but he was drafted to offer text on economic issues. It seemed the most enviable of times for a young conservative writer and thinker.

Except for one thing: it was the summer of 2001.

Frum’s youngest daughter, Beatrice, was born in December 2001, three months after 9/11. He wrote in Newsweek, over a decade later, that his wife had nursed their newborn as F-16s screamed overhead. It was a perilous time for everyone, but especially for someone working in the White House, where staff briefings outlined plans for dealing with biological attacks, car bombings, targeted assassinations, and poisonous gas releases. It was in this fraught atmosphere that president Bush started laying the groundwork for launching the invasion of Iraq, a course of action now widely viewed as strategically flawed and, worse, morally disastrous in that it was based on a lie.

It’s been seventeen years since the war began, leading to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people (if not more). In the intervening years, Frum has many times admitted it was a bad decision, that he would do things differently if he knew then what he knows now. (He does not, however, like to use the word regret.) During our conversations, he didn’t try to evade culpability by pointing out that his influence in the White House was negligible, that he was a speechwriter, not an adviser. Still, whether he was an adviser or a hired pen, whether his role was lead or minor, his part in shaping the Iraq War narrative has defined him ever since, for one reason primarily.

One day in late 2001, Frum was at work in the White House when Gerson came in and asked him to assist with the Iraq sections of the upcoming State of the Union speech. He posed the assignment as a “what if”—what might the president say about Iraq and the current state of global affairs if he were to pursue this or that course of action. Frum told me that everything he wrote was “in the conditional,” meaning that, as he was writing it, he believed he was spitballing. Frum originally wrote that Iran, Iraq, and North Korea comprised an “axis of hatred.” Gerson and fellow speechwriter Matthew Scully apparently liked the phrase and made a small adjustment. After Frum had delivered his notes and wordsmithing to Gerson, he was effectively out of the loop, which was why it came as a shock to him, as he and his wife were watching the speech on TV later in January, when Bush started railing about the Axis of Evil.

The phrase immediately became a flashpoint among both allies and enemies in the US and around the world. It was a succinct encapsulation of the Republican state of mind post-9/11, a pithy string of code that reinforced the long-simmering conflict as an urgent moral crusade.

Axisgate soon followed, wherein Crittenden sent an email to family and friends—one that Slate intercepted and published that February. “My husband is responsible for the ‘Axis of Evil’ segment of Tuesday’s State of the Union address. It’s not often a phrase one writes gains national notice,” Crittenden wrote. “So I’ll hope you’ll indulge my wifely pride in seeing this one repeated in headlines everywhere!!” The leak created a gossipy stir in the Georgetown cocktail-party circuit, but setting aside the unfortunate obliviousness of the email and the criticism it brought the family, the episode gave Frum an air of celebrity and cemented the image that he was deep inside the Republican machine. This was an astonishing ascendancy. If you were a right-winger, Frum’s work may have seemed like the ascent of a thinker and writer to his rightful place. Those to the left might have considered him not just a traitor to his country but to his mother’s legacy.

Frum’s time in the White House did not last long, however. He told me there were many reasons for leaving. One particular area of concern was his disagreement with the president’s high steel tariffs. “I wanted to shift from speechwriting—and political communication generally—to domestic policy work,” he explained. (Others, including writers in the New York Times and the Guardian, speculated that Frum was pushed out of the White House for his wife’s email indiscretion.) Whatever the reason, Frum took his leave that February and joined the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), a right-wing think tank.

Though out, Frum appeared to remain an insider. He quickly wrote a hawkish book, with Iraq War architect Richard Perle, which proclaimed the necessity of American global hegemony. This was followed by The Right Man, an account of the Bush presidency arguing that, whatever one thought of his record, the man himself was admirable. If Frum harboured hunger pangs, wanting to bite the hand that fed him and expand on his earlier project of examining the fault lines within the conservative movement, he hid them, at least for a few years.

Toward the end of the Bush era, he published Comeback: Conservatism That Can Win Again. It came on the heels of the Republicans losing Congress in 2006 but before Barack Obama’s rise. The book was significant for Frum because it recast him on an intellectual course rather than a policy one. Much like his Dead Right debut, Comeback argued that the right had lost its way and needed a major reset. Since Reagan, conservative ideology had held that the only way to make small government better was to make it even smaller and that the only good tax was a lowered tax. Frum contradicted both of these shibboleths. He also proclaimed his support for a carbon tax and, later, voiced his support for gay marriage. “The party needed to reinvent itself for the twenty-first century,” Frum told me. “The Cold War gave shape to Republican ideology for a generation. The party wandered until 9/11, when it seemed that Islamic terrorism would take the ideological place, as it were, of the Cold War. Obviously, the terror attacks were a terrible thing and they called for a response, but you couldn’t reorganize your whole politics around foreign terrorism. To some degree, I was part of that. But it was just wrong.”

The approach outlined in Comeback offered the GOP a set of ideas to rally around, to which it said, Thanks, but no thanks. Not only did the party reject the kind of regeneration Frum was advocating, but it also seemed to double down on the same kind of unreconstructed hyperbole and hysteria that surrounded the Iraq War. The path the Republican Party followed led to the continued growth of Fox News, the creation of the Tea Party, and, ultimately, the emergence of Donald Trump. It also led to the excommunication of David Frum.

It would be an insult to true explorers to describe a man with a cushy post at a high-profile think tank as wandering in the woods, but nevertheless, after Obama entered the White House, in early 2009, Frum’s profile was as low as it had ever been. Yes, he was still publishing here and there, and he was no doubt engaged in some arcane political activity at the AEI, but he was standing on the edge of the dance floor. This interstitial period gave him time to ponder where he was going with his writing and his career, reflections that inevitably led back to growing up in the Frum household. The harsh truths of mortality may have been ever-present as Frum was growing up, but so too was intense political and intellectual engagement. Frum remembers his mother as a serious-minded person, and he describes her influence on him as “limitless.” I asked him what it was like to evolve as a thinker in his own right, moving to the right of the spectrum, knowing his mother was such a famous upholder of liberal causes.

“People say, ‘You and your mother had such different politics,’ and that’s not exactly right because my mother didn’t have politics the way people who have politics have them. She was a profoundly nonideological person,” he said, adding that his mother was someone who took every issue, every conversation, every point of debate at face value, starting at zero every time. She never approached an idea with a preset ideological bent. Frum shared this anecdote almost wistfully, as if part of him wished he had the capacity, or the opportunity, to do the same. “One of the reasons I so desperately miss the opportunity to talk to her is, with most people I know, even the most brilliant intellects, I might not be able to guess all the insights they would bring to a question, but I would know approximately what they would say. I know approximately what Chris Hitchens would say about Donald Trump. I can’t imagine the jokes he would make and the sparkling witticisms and the particular insights and details—that’s why we miss him—but I know approximately where he’d be.” Barbara was different. “What she taught us was not what to think but how to think. She was outside of all ideological categories, a profound analytical intelligence. And incredibly morally sensitive and morally demanding, of herself above all. I learned that from her, how to do that.”

These values were sorely tested during the Obama years. Although he was firmly seated at the AEI, Frum was already standing in uncertain relationship to the conservative movement. He respected Obama but did not support many of his more activist social policies, yet neither did Frum believe the GOP was positioning itself to appeal to most Americans. In March 2010, as Obama was signing the Affordable Care Act into legislation, Frum published on his website an essay titled “Waterloo,” in which he stated that, far from Obamacare being a Waterloo for the president, it would be the undoing of the GOP because the party failed to see that it was what Americans wanted. He made the case that the right should stop politicizing something that was good for the country and do its best to make the program better and more conservative-friendly. Republicans, he wrote, “followed the most radical voices in the party and the movement, and they led us to abject and irreversible defeat.” He rebuked Fox and conservative commentators for lying about health care and stoking a culture war. Rush Limbaugh said that he wanted president Obama to fail, wrote Frum, though “what he omitted to say—but what is equally true—is that he also wants Republicans to fail. If Republicans succeed—if they govern successfully in office and negotiate attractive compromises out of office—Rush’s listeners get less angry. And if they are less angry, they listen to the radio less, and hear fewer ads for Sleepnumber beds.”

The firestorm was immediate. The essay drew over a million views, crashing his site. Frum was castigated by fellow conservatives and, days later, fired from the AEI. Years afterward, writing in The Atlantic, he remembered how, because of that essay, “old friends grew suspicious and drifted away” and that he heard second- and third-hand “echoes of unpleasant explanations for my deviation from the ever-radicalizing main line of Washington conservatism. Increasingly isolated and frustrated, I watched with dismay as people I’d known for years and decades incited each other to jump together over the same cliff.” That essay, he wrote, was effectively his “suicide note in the organized conservative world.”

During the early years of the first Obama term, it seemed like both the left and the right were wondering precisely what was happening to David Frum. “As the Tea Party has come to dominate the GOP, Frum has been transformed in a remarkably short period of time from right-wing royalty to apostate,” wrote Michelle Goldberg for Tablet in 2011. “His writing, once aggressive and hyper-confident . . . now seems elegiac.”

“I’m sure you’ve heard the saying that, if you want a friend in Washington, get a dog,” Frum told Goldberg. “I have three dogs.”

In 2012, Frum went on to publish a book about Mitt Romney’s defeat, and two years later, he found the home that would effectively launch him on his current trajectory, that of senior editor at The Atlantic. From that platform, he has continued his mission to goad the conservative movement to adopt a less ideological and more centrist space. He has chronicled his intellectual evolution: about same-sex marriage, the environmental movement, the value of effective government, universal health care, and the nature of military conflict. He has never apologized for his prowar positions, but he’s expressed some remorse, to varying degrees, about certain hawkish stances he took in his Bush years.

If many were curious about the precise nature of Frum’s working political philosophy toward the end of the Obama administration, those questions would soon be erased. Not long after Donald Trump walked down that escalator in June 2015 and announced he was running for president of the United States, Frum initiated his impassioned, comprehensive, and nearly all-consuming exploration of his contempt for the man who, he tweeted two years later, was “the worst human being ever to enter the presidency, and I include all the slaveholders.”

The depth of his investigation into the amorality of not just Trump but Trumpism has clarified and intensified his sense of what politics ought to be about. It has produced some of his best and most compelling writing. It also may have consigned him to post-Trump irrelevance within the Republican Party.

In a seminal essay in The Atlantic, published on May 31, 2016, titled “The Seven Broken Guardrails of Democracy,” Frum outlined his major oppositional stand to Trump, who had then all but secured the Republican nomination. Read today, the essay is notable for its fury and predictive accuracy. “Here’s the part of the 2016 story that will be hardest to explain after it’s all over,” Frum wrote. “Trump did not deceive anyone . . . all of them knew, by the time they made their decisions, that Trump lied all the time, about everything. They knew that Trump was ignorant, and coarse, and boastful, and cruel. They knew he habitually sympathized with dictators and kleptocrats—and that his instinct when confronted with criticism of himself was to attack, vilify, and suppress. They knew his disrespect for women, the disabled, and ethnic and religious minorities. They knew that he wished to unravel NATO and other U.S.-led alliances, and that he speculated aloud about partial default on American financial obligations. None of that dissuaded or deterred them.”

He went on to describe it as baffling and sinister that any of his conservative friends were even considering voting for Trump, let alone publicly going over to the dark side, yet many did. “Whatever the outcome in November,” he wrote, “conservatives and Republicans will have brought a catastrophe upon themselves, in violation of their own stated principles and best judgment.”

It was the start of what has become the overriding theme of Frum’s work, in articles and books, over the last four years and counting: to detail both the ways in which Donald Trump is individually corrupt and the ways in which Trumpism has peeled back the dressing to reveal the suppurating sore that is the Republican Party.

Ross Douthat is a columnist with the New York Times and, in many ways, may be his generation’s Frum—an idealist trying to think his way toward a refreshed classical conservatism. He told me by phone earlier this summer that he’d been reading and learning from Frum since Dead Right, though he did not always agree with him. Right from the start, Douthat said, Frum saw Trump as an urgent threat and argued that working with him, attempting the incrementalism of reforming the man by degrees, was not going to save the party. “I thought some of his attacks on the GOP were over the top or counterproductive,” said Douthat. “He thought that the infrastructure of conservatism was rotten and you couldn’t just renew it from within. You had to confront the rot. I think the rise and success of Donald Trump suggests that David was more right about the scale of the rot than we were.”

Frum has written hundreds of thousands of words since his “Guardrails” essay, but what unites them all is how deeply offended he is by Trump. There is a faint melancholy there, a wish for the good old days when people could argue about ideas and rail against the injustices of this or that policy as opposed to having to continuously document the race to the bottom. There are no high roads or low roads. Every road leads to Trump, and all are cratered, muddy, dangerous thoroughfares to a destination not worth getting to. His first book devoted to the president, 2018’s Trumpocracy, was essentially an analysis of how Trump happened. Trumpocalypse, published this May, is a strategy for erasing the stain. Frum seems to be feeling the stress: he wrote wearily in Trumpocalypse that “we have to believe this shameful episode will end soon . . . Over the past four years, I have thought and spoken and written about Donald Trump almost more than I can bear.”

Not everyone has been particularly sympathetic. William Voegeli, a senior editor of the Claremont Review of Books and noted conservative commentator, told me that, “at some point, if you want followers, if you want somebody, somewhere, to be on your side, then you have to make clear what that side is. David has been better, more vigorous about what he’s against than what he’s for. There are just so many ways that even a gifted writer can say Donald Trump is a bad president. I’ve found it harder and harder to figure out where David actually stands, if indeed he still considers himself a conservative.”

That’s a polite way of saying what others are saying less politely. Many on the hard right loathe Frum, partly for the content of his criticism and partly because he broke ranks. Fox News host Greg Gutfeld, in a June tweet, wrote, “Frum woke one day, a zero; a failed, bitter scold whose desire to be loved thwarted by events. now, all he does is fume. thinkers find him sad & discuss it openly. He’s the old neighbor who shouts thru the walls cuz his life, and yours, passed him by.” Tucker Carlson, also of Fox, announced on air: “The awfulness of David Frum may be the only thing the left and right agree on in this country.” (He’s not wrong. From a review of Trumpocracy in socialist magazine Jacobin: “as an account of how and why Trump came to be, let alone what can be done to resist him, Trumpocracy fails in almost every respect . . . the hypocrisy of its author proves impossible to ignore.”)

“I think he’s definitely a man without a home,” Douthat told me. “He’s more alienated from what conservatism is right now than I am and than a lot of people who opposed Trump in 2016 but who have stayed squarely on the right are. There’s definitely a form of liberalism that he would be totally comfortable in. It’s just unclear whether it exists as a force within liberalism today. I think,” Douthat concluded, “that David is one of the more betwixt-and-between figures.”

Around the same time that Frum squared off against Bannon at the 2018 Munk Debate, he published an essay in The Atlantic, titled “The Republican Party Needs to Embrace Liberalism,” in which he called for a new brand of Republicanism. “In a democratic society, conservatism and liberalism are not really opposites. They are different facets of the common democratic creed,” he wrote. “What conservatives are conserving, after all, is a liberal order.” He expanded upon those comments during one of our conversations. “In the North American context,” he said, “it’s not like conservatives are conserving the Inquisition. They’re not conserving kingship. The conservatives are part of a liberal tradition in North America.”

At one point near the end of our communications, I asked him whether, given the overall tenor of his policy positions, it had ever occurred to him that he might be a liberal stuck in the body of a conservative.

He did not respond.

As we move toward November 3, Frum does not believe Trump has a chance of winning, but that doesn’t mean he thinks the election will be peaceful. “It’s going to be a very scary and unstable time,” he said. “And, of course, it doesn’t end in November. We’re not safe until January. He will try to cause as much chaos as he can on his way to losing, and then after he loses, he will pardon criminal associates, he will try to pardon himself, he will move money to himself, and he will try to leave behind as poisoned an environment as possible.”

But what if he wins? I asked. What if he legally, legitimately wins? Then it’s full crisis mode, Frum said, not just for America but for the world. “Scorched earth. My God, it’ll be gruesome. It’ll be a sign that the American democratic system has been truly corrupted because, if he wins, he will win despite a big majority of the country being against him. So it will be a win either through massive voter suppression or a massively unfair outcome in the electoral college. How do you even talk about this being a democratic system of government anymore?”

I put it to Frum that, though he is considered a key conservative thinker, he might actually be more on the outside than he’s ever been. The blunt reality is that, as a former warmonger, he will never be embraced by the left, and he is now loathed by the right as an apostate. There is no centre.

“I think I’m a pessimist by temperament and an optimist by opinion,” he told me. “Or at least I try to be. And it is probably true that my first assessment of any situation is the pessimistic one, and then I ask myself what my father would say, and then I try to talk myself into the more optimistic view.” Despite everything, he actually feels quite good about the world these days, mostly because, he explained, the various upheavals have instigated “movements of social and moral change, outside the political system, outside the party system, that I think are inspiring people to be better people.”

I asked him what he actually thought he was achieving by criticizing his party and calling out the hollowness of its leadership, not just in the Trump years but effectively since the twilight of the second Bush term. What’s the plan, the point, the endgame? Surely the goal is not to seek alienation from every point on the political compass, not to mention a chunk of his personal and professional peer group. He thought about that for a minute.

“Life is like a hike through a really overgrown trail, and you’re so busy not falling off the cliff, so busy pushing aside the branches. But, every once in a while, there’s a break, and you get a wider vista. I remember Bill Buckley gave an interview in 1970,” he said of the leading thinker who often railed against the anti-intellectual strain of the Republican Party, “in which somebody asked him, What do you think you’re doing? And he said, I’m trying to maintain a landing strip in the jungle. Someday the planes will appear, and we’ll be waiting for them.” Frum went on to describe a recent family dinner where his career choices were a topic. “We were talking about some of our friends who have gone over to the Fox News side. And there’s a lot of money to be made over there. I was being teased, ‘Are you quite sure about all of this?’ Part of it is my nature: I just don’t think it’s in me to have done that.”

I asked him if he thought his mother would have respected him if he’d made that leap.

“No, she would not,” he said immediately. “Boy, would she not have.”

Maybe the long game, then, is the only one left to play, the only one that might someday put Frum and his philosophy back at the heart of the matter. I asked him if he ever saw himself working in government again. “I don’t think about it,” he said. “Over the past twenty years, I’ve come to use the word useful as a compliment more and more often. I want to be useful. I think it’s also that I have a sense of other periods of my life when I did things that were not useful.” He thought about it for a second longer. “And I’ve got a kind of karmic debt to the universe that has to be paid back.”