“In a culture inured even to the shock of the new,” writes Peter Biskind in his now classic book, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex–Drugs–and–Rock ’n’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood, “’70s movies retain their power to unsettle; time has not dulled their edge.” We are still drawn to the raw power of these films—their pockmarked veracity as much as their slavishness to their creators’ undiluted vision. Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Robert Altman, Roman Polanski, and others, ushered in an era in which the director—former tool of the studio and hired gun—became like a god at whose feet Hollywood and its audience of millions genuflected.

Fast-forward a couple of decades to a time not dissimilar in its politics; simply substitute Iraq for Vietnam. Now replace film with cable TV. Starting in earnest with The Sopranos in 1999, through The Wire, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad (which just concluded its much-hyped final season), we are unquestionably living in television’s auteur age or, more precisely, the age of the showrunner.

For the uninitiated, “showrunner” is a catch-all term for the creator-writer-producer figure who heads most television shows. He or she (but mostly he) is the person through whom all creative decisions flow. The position has always existed in some form or another, but it coalesced over the past fifteen years or so, as cable channels opened their minds and their wallets to edgier television. Lately, the showrunner has been further elevated. The Hollywood Reporter now publishes a list of the Top 50 Showrunners, while, in his summer non-fiction blockbuster Difficult Men, Brett Martin takes us Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution. At this year’s Comic-Con—where thousands shelled out top dollar to watch pasty, sweaty creatives discuss the intricacies of their shows—a documentary about them called Showrunners secured distribution. The trailer features a dozen celebrity showrunners—J. J. Abrams, Joss Whedon, Jane Espenson, Ronald D. Moore, Terence Winter, among others—chronicling their lives and work, yet one figure is absent from the hoopla: Chris Haddock.

A year before The Sopranos debuted, kicking the rolling rock that was the cable revolution, Haddock created, wrote, and sold a show to CBC called Da Vinci’s Inquest. It’s a dark, gritty series about a Vancouver coroner, based on real-life coroner Larry W. Campbell, who later became the city’s mayor. Known for his charismatic wit, sharp dress (think fedoras), and harm reduction advocacy, he is largely responsible for Vancouver’s controversial safe injection facility, Insite. Haddock admired Campbell and turned him into a flawed, at times reprehensible character. Then he set him in ’90s Vancouver, captured down to the last rain-soaked detail, and shot the crusader’s stories in a hand-held, cinéma-vérité style over long plot arcs, which often went unresolved for an episode or a season, or even in perpetuity.

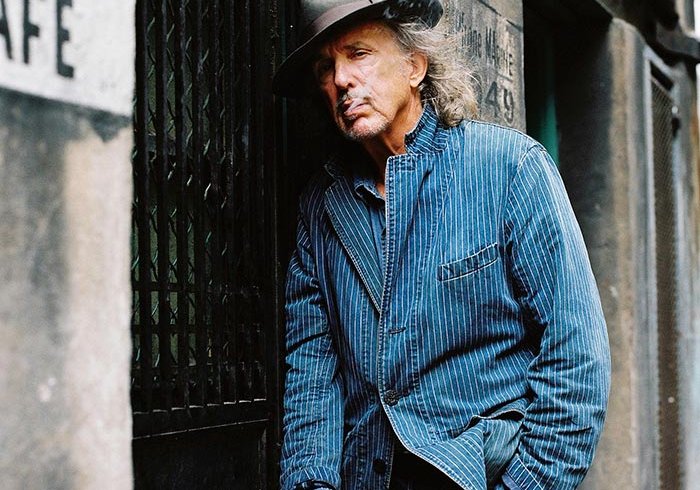

Sound familiar? To any current TV devotee, it should, but it was anomalous in Canadian TV at the time—maybe still—and so was Haddock. Like most of the “difficult men” shaping the medium, he is a staunch perfectionist with a hippie’s aversion to authority. Long before his career in television, he was a busker who later wrote and performed street theatre. He looks like a rock star and talks like a college professor, often repeating thoughts thrice, in strict adherence to the ever-powerful rule of three.

“I met a lot of universal characters busking,” he says over the phone from Vancouver, still his home base. He learned screenwriting from the script for Robert Towne’s The Last Detail, which he checked out of the library when a friend suggested he further explore a character he had written for a musical. In the ’80s and early ’90s, he was hired to write for shows like Danger Bay and MacGyver; eventually, he ventured to Los Angeles, where he sold a few scripts, but he soon returned to Vancouver to raise his two small children. On little more than the strength of a short-lived CBC comedy he created, called Mom P. I., he sold the broadcaster Da Vinci’s Inquest. At first, higher-ups fought Haddock on his storytelling style, but over time they saw the audience’s investment and stopped complaining.

About the period of filmmaking discussed in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Susan Sontag wrote, “It was at this specific moment in the 100-year history of cinema that going to movies, thinking about movies, talking about movies became a passion among university students and other young people. You fell in love not just with actors but with cinema itself.” From a passion, it became a pursuit, with critics like Pauline Kael giving it the same weight as literature. What mainstream criticism gave to cinema, the Internet has given to television: a hub for (over-)analysis. What to discuss? The off-kilter, messy protagonists of auteur TV, of course.

The violent yet tender Tony Soprano, the self-obscuring Don Draper, the now unbridled Walter White, the repressed Piper Chapman—today’s TV heroes are tragicomic human question marks, thwarted as much by their own tortured vanities as by the circumstances that frame their day-to-day. In other words, they are human, yet not quite flesh and blood and therefore prime for scrutiny.

For a super-fan of Inquest, this new age in audience-television relations comes as a massive relief. I was fifteen when the show debuted, and I had no language or forum to vent my feelings about Dominic Da Vinci (Nicholas Campbell). He seemed so real to me. For one thing, he actually spoke like someone from British Columbia, my home province. But, perhaps more importantly, I saw an adult in an important job who was also a fuck-up and sometimes even a dick. It was a bit like learning that your parents are people, too.

On the positive side of the ledger, Da Vinci was good at what he did, and he enjoyed it, despite the brutal nature of a coroner’s work; in this way, he was a lot like Breaking Bad’s Walter White. He was a truth hound—a bit of a woodpecker, tapping at cops and crooks alike to convince them to do better, hammering away at something resembling justice in a convulsed city of addicts and missing prostitutes. (That Haddock had the wherewithal to address what would later become the Robert Pickton case is just one of the show’s astonishing-in-retrospect qualities.) Like The Wire’s Jimmy McNulty, Da Vinci was bad at relationships but great at dogged pursuits, often with no noble reasoning other than a stubborn need to find the story’s elusive end.

And like so many of today’s TV protagonists, he was a character made in his creator’s likeness. “The men who seized [the showrunner role],” Martin points out in Difficult Men, “would prove to be characters almost as vivid as the fictional men anchoring their shows.” During and after Inquest, in his quest for absolute creative control, Haddock developed a reputation for being unyielding, especially with CBC brass, a fact he’ll readily admit (the tendency not just to be difficult but to boast about it is yet another fascinating showrunner trope). “Everything affects the story, and the story affects everything,” he now explains, “so I want to make sure that if things need correcting or someone has a brilliant idea, it gets incorporated. If the wardrobe mistress has a great idea and it’s not to do with wardrobe, you want to be there to respond to it.”

After seven seasons of this kind of thing, Inquest culminated with the protagonist’s announcement that he was running for mayor; Da Vinci’s City Hall, a subsequent series, was cancelled after just thirteen episodes. Next came the marvellous Intelligence, a take on the Canadian Security Intelligence Service that Slate called the “Canadian Wire,” also cancelled abruptly after two seasons.

In the wake of these disappointments, Breaking Bad showrunner Vince Gilligan sat on a panel with Haddock at the Vancouver International Film Festival. Already a fan, Gilligan heard Haddock wax poetic about television and hooked him up with HBO executives, which led to an opportunity to work on ex-Sopranos writer Terence Winter’s Prohibition gangster drama, Boardwalk Empire. Haddock signed on as co-executive producer in the series’ third season, billed alongside two other names you might recognize: Martin Scorsese and Mark Wahlberg.

It says much about the strength of the creative’s hold on TV that a weirdo Canadian with an obsessive streak and an erratic professional history could charm his way to the front of one of the most elite writers’ rooms in the industry. What happens once he’s there says just as much about the DNA of a showrunner. By this writing, Haddock had moved on from Boardwalk. The deal with HBO was just for one season—long enough to test the relationship, perhaps, but not so long that the two men would step on each other’s toes. Winter could not be reached for this story (perhaps in part because of the recent death of his close friend and collaborator James Gandolfini). Haddock, meanwhile, is strategically discreet about the details, but it is hard to imagine him happy confined to the writers’ room.

He is the credited writer on a single episode from season three, “Bone for Tuna,” in which the masochistic Gyp Rosetti (Bobby Cannavale) makes a power play for the rum-running business of protagonist Nucky Thompson (Steve Buscemi). In many ways, it feels like vintage Haddock—darkly and dryly witty, swiftly paced yet imbued with the awkward slowness of everyday life, its characters’ ambitions crushed by hubris, nihilism, or worse—but Haddock makes it clear he was not at the helm. “I wasn’t sure what was going to end up in the final draft. It’s an ongoing process, until the thing is ripped out of your hands.” Here he pauses. “I’d find it difficult to have that job again.”

In some ways, it is easier to be a showrunner in Canada: smaller crews and budgets mean the disparate duties that ended up under the showrunner mantle have long been status quo here. “It’s always proportionate. Everything’s smaller,” says Jessie Gabe, head writer on CBC’s hit comedy Mr. D. Technically, Mr. D’s showrunner is Gerry Dee, the stand-up comedian who also stars. This arrangement sets a precedent in Canadian TV, analogous to the FX series Louie or NBC’s 30 Rock.

Tim McAuliffe started on This Hour Has 22 Minutes before heading to New York, where he was speed-hired for Late Night with Jimmy Fallon, followed by stints at other NBC flagships, Up All Night and The Office. Right now, he is in LA writing for the new CBS series Bad Teacher. Crucially, he is also developing a series for CBC, which remains under wraps. “When I left, Canada wasn’t a great place for comedy TV,” he says. “That’s changed.”

Still, you can’t create Breaking Bad in Canada. Even if you could achieve a comparable production scale, you would hit a brick wall with marketing. So Haddock has decided to muscle it out in LA. He has “in development, writing, dealing—a half-dozen to a dozen projects going at once.” Most TV execs, he says, want something “uniquely the same,” a concept that conforms to a known structure but gives it a new sheen. “They don’t want people to have to torture themselves for the first ten to twenty episodes trying to figure out what the show is,” he says. “There’s a tendency to try to nail down a brand, or a property, or a well-known character. Endless Sherlock. It gives a confidence factor to the people in the room.” In this context, it takes a strong will and a prolific pen to create and sustain a vision, let alone a dozen.

In that sense, he is grateful to Canada, and for Da Vinci’s Inquest in particular. “I could sit up here in the pocket and feel really confident that I had a show that would be on the air for a couple of years,” he says. “That allows you to test the boundaries of your skills.” Fifteen years later, in the era of the showrunner, he must feel this is his time. The story has all the makings of a serial drama, starring the tragicomic human question mark, thwarted as much by vanities as by circumstances, etc., etc. To find a place on that Hollywood Reporter list of Top 50 Showrunners, he must endear himself to the right audience, at the right time, in the right place. He will need to be a difficult man, but not impossible.

This appeared in the November 2013 issue.