Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Over the past year, as Canadians have rushed to take advantage of record-low mortgage rates,1 home sales across the country have surged. We asked Diana Petramala, a real estate economist, to weigh in on what this means for the future of buying and selling.

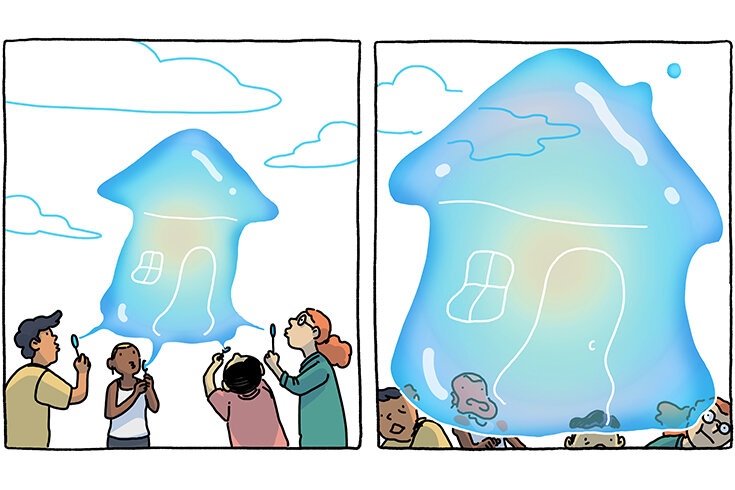

Historically, housing bubbles, when property prices far surpass actual property values, have eventually burst. There’s been debate over whether Canada is currently on this trajectory. Is it?

I identify a housing bubble by double-digit annual home-price growth for five years followed by a sustained decline for a much longer period. Right now, we’ve seen this level of national growth for only about a year, so there is still room for prices to run up.

How it turns out is going to depend on policy. There have been calls for higher interest rates to cool the market, but I believe that would lead to a crash. When rates increase, those who bought expensive houses and have to renew their mortgages may not be able to afford them and end up selling, likely for much less than they paid. This could put more households in a financially vulnerable situation.

For now, interest rates remain low, so I think that could create another acceleration in sales. What happens in 2022 will be determined by how many people decide to sell.

Canada’s last housing bubble burst in 1989, following a boom in Ontario in the ’80s. Does the pandemic real estate boom resemble that cycle?

The 1980s boom was driven by a decline in interest rates and changing demographics. At the time, a lot of boomers wanted to be homeowners. Many of them moved to Toronto2 because that’s where the economic prosperity was. The problem was that the supply couldn’t respond fast enough to the demand, which is also what’s happening today.

The difference is that, this time, the increase in prices is happening across Canada, and it’s now millennials who are in the peak age group for first-time home-buying. This demographic had been accumulating less real estate than previous generations3 but more savings, so many had down payments that allowed them to jump straight into the market. At the same time, boomers are cashing in on their expensive houses and moving out. Everybody wants to buy and sell all at once, and nobody knows how that’s going to play out. Now, we could be on track to beat the escalation in prices that we saw in the ’80s in Toronto.

Real estate demand is so high that some experts are predicting a supply crisis across Canada.4 Is this preventable?

The problem is that we’re responding to today’s demand with housing that isn’t going to be ready for a few years. If interest rates go up, then you end up with a whole bunch of new supply but far fewer people who can afford it.

Also, as cities grow, there is less space to build, and housing prices rise because the cost of land goes up. For this reason, developers want to build more condos so that they can spread the cost of the land across more units. The real problem is the shortage of middle housing, like duplexes, townhomes, and courtyard apartments. It’s really unprofitable to build it, but we need more of it.

Beyond the risk of a crash, do you think the hike in prices we’re seeing now could have any other long-term effects on the economy?

Part of Canada’s success has been its ability to attract skilled immigrants. If it becomes harder to afford housing and even find rentals, it’s going to be increasingly difficult to attract newcomers, who are vital for the long-term economic health of the country.

1. Last December, for the first time in Canadian history, home buyers could get a five-year mortgage rate below 1 percent. In 2019, the average was 3.14 percent.

2. During the late 1980s, the average price of a Greater Toronto Area home more than doubled over three years.

3. According to Statistics Canada, at age thirty, 50.2 percent of millennials owned their homes compared with 55 percent of baby boomers.

4. Canada has the lowest number of housing units per 1,000 residents of any G7 country.

As told to Sean Wetselaar. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.