On the morning of May 11, 2015, Michael Nehass waited for his trial to begin at the Yukon Supreme Court. He seemed nervous, fidgety. Several blocks away 150 people would soon begin filtering into a downtown Whitehorse hotel for the jury selection. Nehass stood accused of forcibly confining a woman in an apartment building, holding a knife to her throat, and threatening her and her family. The assault allegedly occurred in December 2011 in Watson Lake, a community five hours southeast of the territorial capital.

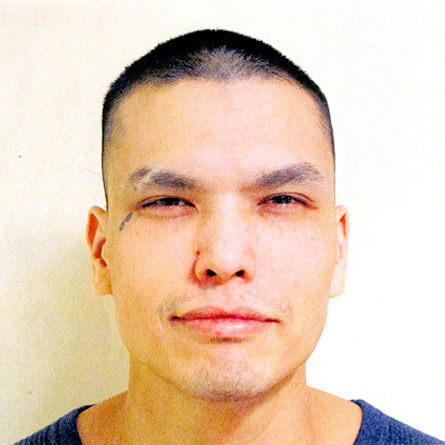

The thirty-one-year-old member of northern British Columbia’s Tahltan Nation had lost weight during his three-and-a-half years in custody—his cheeks sunken, skin stretched taut across his jawbone, his forearms thin. Under his right eye were two tattooed teardrops. Standing behind a wooden table Nehass wore the Whitehorse Correctional Centre uniform: red shirt, red pants, and socks. He told the judge he was worried the jury would be biased against him because of media coverage of his case, so the crown prosecutor made him a last-minute offer: a judge-only trial. Nehass declined.

The judge told him potential jurors would be asked whether they could set aside anything they’d read about Nehass in the news. If they said no, they wouldn’t be selected. Then Nehass asked for something: Could each person in the jury pool hold a paperclip to determine whether the government had implanted a nanochip into his or her brain?

After his arrest in Watson Lake in 2011, Nehass was taken to the only adult jail in the territory, and has been there since. Due to various delays in his case, he waited in custody for more than three years to stand trial. Last May, once the jury reached a verdict—guilty of forcible confinement, assault with a weapon, and breaching his probation; not guilty of uttering threats—Nehass was returned to jail to wait for his sentencing hearing. Seven months later, he is still waiting. December marks Nehass’s fourth year in custody on remand, an unusually long time considering 78 percent of inmates who were awaiting a trial or sentencing across the country in 2013–2014 were held for one month or less.

According to reports from the jail, in May 2013, staff decided Nehass was “unmanageable” in the general-population area. He’d been repeatedly violent and threatening to other inmates and guards. So he was moved to the segregation unit indefinitely. He’s spent nearly all of his time there since, except for a few months in the slightly less restrictive secure living unit, according to the jail’s reports. In total, he has spent at least two years in solitary confinement at WCC.

For approximately twenty-three hours a day, Nehass is locked in the segregation unit, his cell sparsely furnished with a bed, sink, and toilet. During his only “free” hour he can wander, with his wrists shackled to a belly chain, around the small common area, shower, or use the phone. He can also visit the “fresh-air yard,” an enclosed room with a barred window. Across from segregation is the secure living unit, where cells have a TV and inmates may be allowed out for more than an hour each day.

In an application filed in court last month, Nehass alleges he has been subjected to cruel and unusual punishment at WCC, that his rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms have been violated. As a result, he argues in his court documents, he has experienced “extreme isolation, loss of psychological integrity, loss of well being, and very bad health.”

But until a judge hears his application, scheduled for early next year, Nehass remains in solitary confinement at the Whitehorse jail.

Solitary confinement, or segregation, is widely defined as being locked in a cell for twenty-three hours a day with minimal social interaction. In 2011, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, Juan E. Méndez, called segregation for longer than fifteen days “torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.” Long-term solitary confinement can cause depression, anxiety, hallucinations, confusion, paranoia, and psychosis. Canada’s correctional investigator Howard Sapers has called on the federal government to prohibit the use of segregation for inmates who are suicidal or have mental illnesses.

“It really exacerbates existing mental health problems,” says Catherine Latimer, executive director of the John Howard Society, a national prisoner-advocacy group. If an inmate doesn’t have a pre-existing mental health condition, the society believes time in isolation should not exceed fifteen days. In federal prisons, which house inmates who are serving sentences longer than two years, disciplinary or punitive segregation is well regulated, with firm limits, Latimer says. But administrative segregation—the territorial equivalent of which Nehass has spent some months in—is more of a grey area. According to the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, it may be used to “maintain the security of the penitentiary or the safety of any person by not allowing an inmate to associate with other inmates.” But there’s no legislated cap, and it can be employed at prison staff’s discretion. “That’s what you really need to worry about,” Latimer says.

While the federal government operates prisons through Correctional Service Canada, territories and provinces run jails. These typically smaller facilities are for prisoners serving sentences shorter than two years, or for those who are on remand, like Nehass. While there are no firm numbers on how much solitary confinement is used in territorial and provincial jails, Latimer says she’s aware that it’s used often.

At the 2012–2013 inquest into the death of Ashley Smith at a prison in Ontario, the jury recommended that segregation be capped at fifteen days, and that inmates must be removed from segregation for at least five days before they’re returned—for a maximum total of sixty days in segregation in a calendar year.

The Whitehorse Correctional Centre doesn’t use the terms “disciplinary segregation” and “administrative segregation” like the federal system does, but the jail is structured much the same way. “Segregation” is punitive, while “separate confinement” is for inmates deemed a safety risk. Nehass has spent time in both. Yukon legislation caps “segregation” at thirty days, but, like federal administrative segregation, there is no limit on “separate confinement.”

The nanochips Nehass mentioned before his trial are just one piece of an elaborate conspiracy theory he has created. He has said many times in court that he believes senior government officials are colluding with the RCMP and CIA to keep him behind bars, perhaps even kill him.

Nehass is often frantic and agitated, swearing at and shouting over lawyers and judges. He has said he is scared his food will be poisoned at the jail, and that he had to cover up his cell window because people were whispering threats from the outside. A 2014 report from the jail that’s been filed in court states that staff are concerned for Nehass’s mental health: “He has demonstrated a great deal of paranoia and has been suffering from delusional beliefs.”

In January 2014, the crown prosecutor sought an order that Nehass was unfit to stand trial. He was assessed by a forensic psychiatrist, who said he believed Nehass was suffering from a major mental disorder. He noted Nehass had a history of involvement with mental health services, starting at the age of twelve.

A judge heard the psychiatrist’s testimony and decided Nehass was unfit to stand trial: “It is clear that Mr. Nehass views the prosecution against him and this fitness hearing as an attempt to keep suppressed the information he possesses about individuals, entities and governments being involved in a vast network of conspiracies and cover-ups. I find that this severely impacts his ability to understand the nature and object of the criminal proceedings.”

But two months later, the Yukon Review Board, which oversees people who are unfit to stand trial and not criminally responsible, overturned the judge’s decision. The board decided that Nehass’s delusions didn’t affect his understanding of the court process. Nehass was fit to stand trial.

Nehass’s father, Russell, believes his son’s mental health is declining. He filed a complaint with the Yukon Human Rights Commission last year, alleging Nehass had been subjected to “psychological torture” in solitary confinement. His son had begun talking about Freemasons “controlling everything” and making strange requests, like asking his father to call the Chinese embassy—things Nehass didn’t talk about prior to the months he spent in segregation, Russell said in his complaint.

Last January, the John Howard Society and the BC Civil Liberties Association sued the federal government over solitary confinement, alleging it amounts to cruel and unusual punishment and violates the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Both organizations want to see limits placed on segregation, as well as judicial review of its use on a case-by-case basis.

The trial is scheduled for September 2016, but Latimer is hopeful that, with a new government in power, the matter could be resolved without one. In Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s mandate letter to the new minister of justice, Jody Wilson-Raybould, he instructed her to review Canada’s litigation strategy: “This should include early decisions to end appeals or positions that are not consistent with our commitments, the Charter or our values” and to implement recommendations from the Ashley Smith inquest regarding restrictions on solitary confinement.

Any legislative changes at the federal level wouldn’t be binding for territorial or provincial jails, but Latimer says there may well be a trickle-down effect. “The idea is not to abolish all forms of segregation but to ensure that it is truly a last resort and an interim measure,” writes Queen’s University law professor Lisa Coleen Kerr in her 2015 paper, The Chronic Failure to Control Prisoner Isolation in US and Canadian Law.

Whether or not solitary is being used as a last resort in Nehass’s case will be explored at the upcoming hearing. According to jail reports, even after Nehass was removed from general population, he continued to misbehave. On two occasions, he destroyed the segregation unit using a phone he pried off the wall. He has spit at and threatened to kill guards. “Mr. Nehass has been a significant behavioral management and security concern while remanded to custody at WCC,” one report says.

If Nehass wins his human rights case, he is asking to be released. In court documents, he believes the amount of time he has spent in jail is at least equivalent to the sentence the prosecutor will seek, if not greater.

At a brief court appearance last summer—one of dozens over the last four years—Nehass was in a frenzy, yelling about forced sterilization and robocalls. The judge ordered him to stop making “baseless” allegations. Nehass looked over at the two reporters sitting in the gallery. “Can somebody help me? ” he asked, throwing up his hands. “Can anybody help me? ”